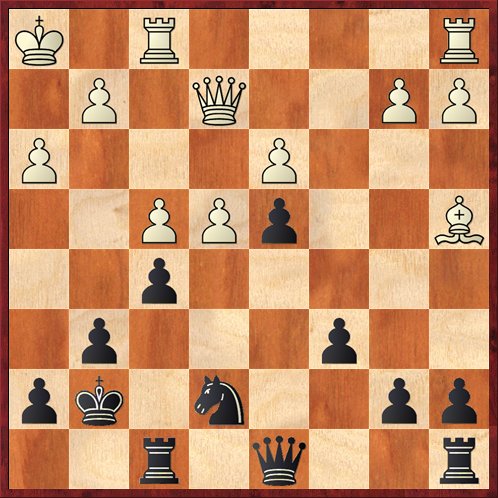

Last night I had a chance to go over all of my games from the New Year Open (my most recent tournament, a month ago) with Gjon Feinstein, my friend and frequent analysis partner who is a national master. We got to an interesting position from my first-round game against Allan Beilin, a class A player who is (I would estimate) about 12 or 13 years old.

“Well, of course, White is doing really well here,” Gjon said. He said it in a matter-of-fact way, as if it would be obvious to anyone.

“No, I think that Black is doing just fine!” I said. To be honest, I was surprised by Gjon’s very rapid and negative assessment of the position. We had gotten here by a series of what I thought were basically correct moves by Black, so if Black is doing poorly here then he is doing poorly in the whole Blackburne Variation of the Bird (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nd4 4. Nxd4 ed 5. O-O g6).

Why do I think that Black is doing okay? It comes down, fundamentally, to the difference between the two minor pieces. White’s bishop has very little function in this position. It can go to b3, but on that diagonal it’s hard for it to attack anything of importance in Black’s position. Only if the bishop somehow got to e6 would Black be worried, but Black doesn’t need to let that happen. On any other diagonal the bishop is useless. The pawn on d3, as usual, stymies its hopes of taking part in a kingside attack.

Meanwhile, Black’s knight is doing a wonderful job of holding together Black’s kingside. Not only that, if White ever exchanges on f5 or plays e4-e5, then the knight will have possibilities of leaping in two steps to e3 and really becoming a monster.

Finally, let’s look at the position in terms of plans. To ask Mike Splane’s favorite question: How am I going to win this game?

The only way for White to win, in my opinion, is to play for g4. I don’t think that g4-g5 will do him any good, as it keeps the positions closed, so he will probably have to go g4xf5 and then try to do something with the open g-file. However, if White ever tries to do these things, first he weakens his f4 pawn, which will require some baby-sitting, and then (more importantly) he leaves a lot of open squares around his king. Black will play … c5 at some point and then be able to harass White’s king on both the a8-h1 and b8-h2 diagonals.

In short, if Black is reasonably alert I don’t think that White’s winning plan really works.

Meanwhile, how does Black win the game? The first order of business is to leave the kingside alone. Black has no interest in trading pawns on e4. (I think that my young opponent failed to realize this.) Black is perfectly happy keeping the tension, because the pawn on f5 keeps the wolves at bay.

I am reminded of something that Bill Brian [mistake corrected 1/31/11 — DM] Wall says: “Two moves is the record length of time for an A player to maintain the tension.” Sure enough, it was my opponent who broke the tension first, pushing e4-e5 five moves after this. (Okay, so at least he beat the “record.”)

The second order of business for Black is to mobilize his queenside pawns. His plan is … a5, … b5, … c5, … a4, and eventually (somehow or other) … c4. And here’s the thing. While White’s winning plan involves putting his king at risk, what are the risks involved in Black’s plan?

That’s right, there aren’t any. It only becomes risky when we get to the point of playing … c4; that will have to be carefully set up and calculated. Until then, we can just sit and shuffle pieces and bide our time.

It’s certainly not the case that Black stands better in the diagrammed position; but he doesn’t stand worse. For what it’s worth, Rybka agrees with me, giving White a 0.19 pawn edge (which is really minuscule) after 18. Bb3.

I see this a lot in the Bird Variation; there’s something about it that fools people into thinking White has more of an advantage than he really does.

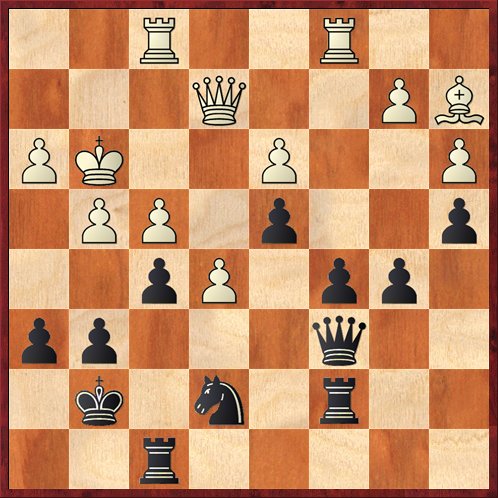

Here’s the position we got to 13 moves later, just after the time control.

As you can see, White has not done very much except bring his king up to g3, which was not a particularly good idea. Meanwhile, Black has set up his pawn formation and is waiting for the right moment to play … Nd5 or … c4. Rybka still says the position is even (although it’s now at 0.00 — dead even — rather than +0.19 for White). However, my opponent turned this into a lost position with two swift moves.

31. Rc2?! g5! 32. Rf3? …

White could still save the game, maybe, with 32. Kh2!, getting the king out of harm’s way. But that is a difficult move to find, psychologically, after White has taken the trouble to move the king up to g3 in the first place.

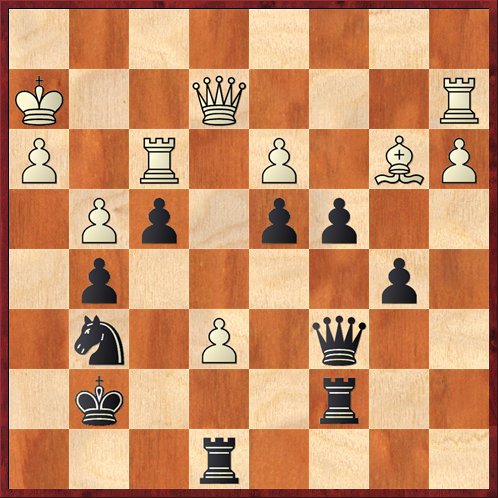

32. … Ng6 33. fg f4+ 34. Kh2 hg 35. b4 ab 36. Bxb3 Ra8 37. Ra2 Re8 38. e6 c4

This is one of those cases where you blink your eyes and ask, “How did things go so wrong for White so fast?” All of a sudden Black controls every key line, while White’s pieces are totally confused. The game finished 39. Rc2 Rxe6 40. Qf1 Nh4 41. Rf2 R7e7 42. Rfe2 Nf3+ 43. Kh1 Nd2+ 44. Qg2 f3 45. Rxe6 fg+ White resigns.

It was nice that the winning move did, in fact, turn out to be … c4. As I told Gjon, “The reason I won this game is that I had a plan and my opponent didn’t.” No, the Bird didn’t win the game for me, but it did get me to a position where White couldn’t figure out what to do.

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

Thanks Dana for this wonderful illustration of the master’s thinking process! Your Bird may not get enough respect in the blogosphere but you surely know how to dissect a position with delightful clarity 😉

I’m a bit puzzled by the fact that you call the difference in minor pieces the key feature of the position. Given your assessment, I would naively say that presence of pawn majorities in opposite sides is even more important, and that Black’s position is preferred since its pawn majority can advance without exposing the K.

Bill Wall? Ouch.

Hi Freelix,

I guess it doesn’t matter which you call the most important feature, because they are both important and they interact. The reason that White has no good attacking plans on the kingside, other than the all-out pawn storm, is that he has no minor pieces over there. Think how much better his position would be, for example, if he had a knight that could come to g5 and team up with the bishop in putting pressure on e6/f7. Or think how much more effective his pressure would be if he could put his Spanish bishop on the c2-f5 diagonal and put pressure on all of those pawns on white squares. So White’s lack of an attack is directly tied to the inefficacy of his bishop. Not only that, his bishop is also unable to *defend* the kingside as well! That’s one reason that playing g4 is such a double-edged sword for White; he has nothing on the kingside (aside from his queen and the e4 pawn, if he leaves it there) to block the long diagonal.

This issue may be why my master friend mis-evaluated (in my opinion) the position. The bishop looks very pretty on b3, but it doesn’t do a thing.

Brian, Sorry! I’ll fix my mistake immediately. This is why I proofread my entries before I post them, but in this case I let one get by. 🙁

Good to see the Bird holding up so well…. A very interesting article.

Brian Wall said that? Ouch!

{ 1 trackback }