Last night I got together with some of my regular chess friends, Gjon, Cailen, and Rich Flacco, along with Mike Splane, who came “over the hill” from San Jose. Mike told me that he is a regular reader of this blog, so I would like to feature a recent game that he showed us, which I found very impressive.

By the way, you can find this game and many more at Mike’s own web page. He is a USCF Life Master (with his title earned the “old” way), and he told us that his game has been undergoing an interesting metamorphosis. He used to be a wild tactical player, but now that he is in his fifties he has gone to a more solid style. He has been very successful with it: he is currently working on a nine-game winning streak and a 31-game unbeaten streak, which are both career highs! It’s really encouraging to me, seeing a person of my age who is playing better than ever, instead of gradually declining as so many of us seem to do.

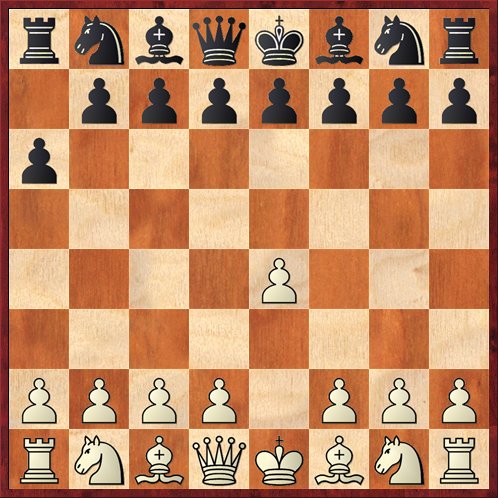

Anyway, one of the openings that Mike has been experimenting with is the Birmingham Defense, 1. e4 a6.

This is one of those openings where Black seems to be thumbing his nose at opening principles. Nevertheless, it was employed by English GM Tony Miles to win a famous game against then World Champion Anatoly Karpov in 1980, in a game played in Birmingham, England. (Thus the name.)

Karpov played 2. d4, allowing Miles to play 2. … b5. Karpov’s move is, of course, good on general principles. It is by far White’s most popular response according to Chessbase. having been played in 1767 out of 2127 games (more than 83 percent).

Nevertheless, I have always wondered why White should allow Black to obtain exactly the kind of pawn formation he is aiming for. Why not instead play 2. c4, preventing 2. … b5? Although 2. c4 has been played in only 4 percent of the games in Chessbase, it seems to me the more accurate move.

Mike said that against 2. c4 he would play 2. … e5, and this move makes a lot of sense. Black is transposing into a double king’s pawn opening with the moves c2-c4 and … a7-a6 inserted. The move c2-c4 messes up the great majority of White’s opening options. The Giuoco Piano, Two Knights Defense and Ruy Lopez are now not even possible. The King’s Gambit would be a disaster because White’s bishop can’t get to c4.

But … there is the Scotch Game. To be more precise, the Four Knights Scotch Variation. Thus, after 1. e4 a6 2. c4 e5 3. Nf3 Nc6 4. Nc3! (Move order is important. White avoids 4. d4 ed 5. Nxd4 because of 5. … Qh4, and Black transposes into a line where White would want to play 6. Nb5 but cannot because of the pawn on a6.) 4. … Nf6 5. d4 ed 6. Nxd4 Bb4.

This is the main line of the Scotch Four Knights, with the moves … a6 and c4 inserted. And this time, for a change the insertions favor White. White now plays 7. Nxc6 bc 8. Bd3, as in the Scotch Four Knights, and Black now cannot play 8. … d5, which is the standard equalizing move in that opening. Therefore it is up to Black to prove he has another route to equality. This position has arisen in exactly one (1!) tournament game, between two Irish players named Sam Collins and Thomas Clarke in 2000. That game was a very convincing win for White, although of course one game doesn’t prove anything.

I think the other sensible option for Black on move two is 2. … c5, which will probably transpose into a main-line Sicilian or English. This is probably why Karpov preferred 2. d4 over 2. c4, because if you get into a main-line anything then you have not really refuted the Birmingham Defense.

But actually, Mike’s games make me think that there isn’t any refutation anyway. That is because unlike Tony Miles, Mike is answering 2. d4 with 2. … c5. No matter what White does (within reason) Black is ready to transpose into a known opening. 3. Nf3 would transpose into an O’Kelly Sicilian. 3. d5 would transpose into a Benoni. And finally there is the move that Cameron Wheeler chose against him, which transposes into something vaguely resembling the Gurgenidze System in the Caro-Kann, only much worse for White…

Cameron Wheeler — Mike Splane

Tuesday Knights Round Robin

December 7, 2010

1. e4 a6 2. d4 c5 3. c3 …

In four games, Mike has gone 4-0 against this move! A good reason to keep playing the Birmingham!

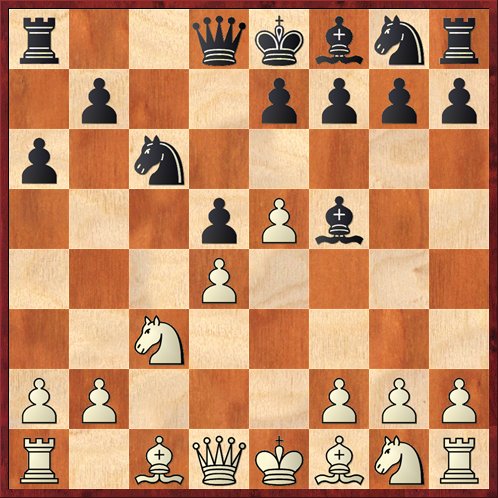

3. … cd 4. cd d5! 5. e5? …

This cannot be recommended. It turns into either a Caro-Kann without a pawn on c6 blocking Black’s knight, or a French without a pawn on e6 blocking Black’s bishop. Either way you look at it, Black is happy.

5. … Nc6 6. Nc3 Bf5

Already Black is completely equal. White’s next move makes things worse, by creating new weaknesses.

7. f4?! e6 8. a3?! …

Probably too slow. It was played to prevent … Nb4, but Mike notes that this was not a threat yet because of 9. Qa4+ b5 10. Bb5+! After White’s move, the initiative is in Black’s hands. Mike now embarks on a slow but hard-to-resist plan, relocating his bishop to g4, his knight to f5, and threatening to play … Bxc3 and win the pawn on d4.

8. … h5 9. Nf3 Nh6 10. Be2 Rc8 11. O-O Bg4 12. Be3 Nf5 13. Bf2 g6

I love Mike’s patience in this game. He can already win the d-pawn with 13. … Bxf3 14. Bxf3 Nxd4. Notice that White does not dare recapture with 15. Bxd4 Nxd4 16. Qxd4?? because of 16. … Bc5! — a recurring theme, and a move that shows the weakness of 7. f4?! However, Mike did want to do this yet because White would play 15. Bxh5, winning the h-pawn for the d-pawn. Even though this trade is favorable for Black, Mike avoided it — because he is planning to win the d-pawn outright!

Can you find a way to save White’s d-pawn? I can’t!

14. h3 Bxf3 15. Bxf3 Ncxd4

Really, chess is so easy sometimes.

At this point we could stop and say Black is obviously much better, a pawn up with no compensation for White. However, I think it is well worth playing over the rest of the game to see how Mike patiently applies the clamp to White, denying him any sort of counterplay. Here are the next few moves:

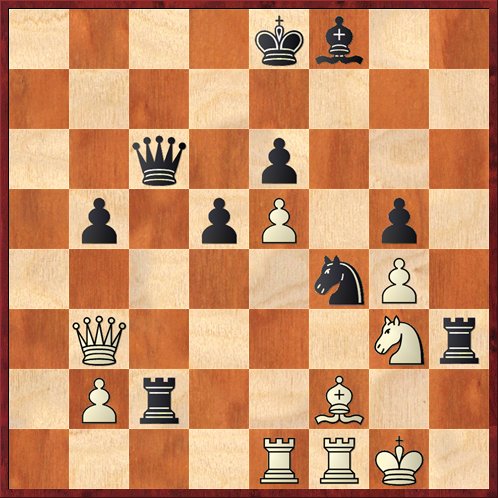

16. g4 Nxf3+ 17. Qxf3 hg 18. hg Nh4! 19. Qh3 g5! 20. f5 Ng6

Cute! The knight is headed for f4 where it will shut down White’s dreams of counterplay.

21. Qf3 Nf4! 22. fe fe 23. Ne2 Rh3 24. Ng3 Rc2 25. Rae1 Qc7 26. Qb3 b5

Here I would be looking at all sorts of exchange sacrifices, on f2 or g3, and they might even work, but Mike has a different philosophy. Instead of giving away your material, why don’t you just wait for your opponent to give you his?

27. a4 Qc6 28. ab ab

Do you see Black’s threat?

Here White played 29. Ra1?, a move that loses immediately. Mike makes a very interesting comment: “When you force your opponent to make a defensive move (… Qc6) that also contains a threat, you often miss the threat.” So true! I have made this same mistake myself, many times.

Mike played 29. … d4!, with an unstoppable threat of … Qg2 mate, and White resigned.

In the diagrammed position, White’s only move to prevent … d4 is 29. Qf3, but then Mike would have played 29. … Bc5! with zugzwang! Check it out for yourself — not a single one of White’s pieces can move without losing material or getting mated. What a great triumph for Michael’s boa-constrictor approach to chess.

{ 9 comments… read them below or add one }

Hi Dana,

Interesting article, but in light of your recent discussion with Dennis on opening theory, I have to ask what is gained with 1….a6? In the game you show with 3. c3 and 4…d5!, after 5. exd this simply looks like a poor man’s Panov-Botvinnik for Black to me. I would agree that there’s a bigger chance you can catch out someone who gets lost when out of book, but 1….a6 seems so extreme. After 1. e4 there are probably only a handful of moves that accomplish less (I’m thinking 1….h5 may be substantially worse). I suppose there’s always a virtue to originality.

I think this question should really be directed to Mike Splane (if he’s reading this)! As I said, Mike seems to be using 1. … a6 mostly as a way of transposing to other openings. But if you want to play the O’Kelly Variation of the Sicilian, why not just play 1. … c5 on the first move and 2. … a6 on the second? Is the move order just a matter of psychology?

Then there’s 1. e4 a6 2. d4 c5 3. d5, which I didn’t analyze at all in my post, except to say that it transposes into a Benoni. But it’s not a completely normal Benoni, and the question has to be asked whether White can use the move order to his advantage.

So I’m not advocating 1. … a6, but I do think that the line 1. e4 a6 2. d4 c5 3. c3 cd 4. cd d5, seen in this game, looks pretty good for Black. Or at least Mike is making it look good!

I should also have mentioned that Mike also showed us two games with 5. ed, your “poor man’s Panov-Botvinnik.” In one of them White played pretty miserably, but in the other one a class-A player did succeed in giving Mike a pretty hard time before losing.

Got it, that makes sense. I do think there is some truth to the psychology of switching moves from 1…c5 2….a6 to 1…a6/2….c5. I wouldn’t advocate either, but I’m sure the latter does throw people off !

Thanks for the very kind write-up.

I haven’t been able to find any way for White to take advantage of this move order but I’ve only been playing this opening for a month.

The idea behind playing 1. … a6 first is to trick people into the O”Kelly line. After 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 a6 3. d4 cd4 4. Nd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 e5 is supposed to give Black a superior version of the Sicilian. But most players know that they need to avoid 3. d4 if you start with the Sicilian move order.

I don’t know if you can edit the blog, but if you can there is a typo in your comment after move 8. It should be BxF3 instead of BxC3.

I like your suggestion in the Four Knights line, 1 e4 a6 2. c4 e5 3. Nf3 Nc6 4. Nc3 Nc6 5. d4 I think Black wants to be playing Bc5 before Nc6, to prevent d2-d4. I experimented with the White side of 1. e4 e5 2. c4 back in the mid 90’s when I was giving simuls, as a way to throw my opponents on their own resources. Finding a way to contest Black’s pressure on the f2-b6 diagonal was always trouble for me. I used to quickly play Na4 but in the line I’m playing, with 1 … a6, the bishop can hide on a7.

Oops! I wrote

” I think Black wants to be playing Bc5 before NC6, to prevent d2-d4″

I meant “I think Black wants to be playing Bc5 before NF6, to prevent d2-d4. ” So the opening would go 1 e4 a6 2. c4 e5 3. Nf3 Nc6 4. Nc3 Bc5

“Nevertheless, it was employed by English GM Tony Miles to win a famous game against then World Champion Anatoly Karpov in 1980, in a game played in Birmingham, England. (Thus the name.)”

Not quite. The game was played in Skara, Sweden. However, Birmingham, England was Tony Miles’ home town.

Great article. I’d looked into the Birmingham Defense and thought it was pretty useless, this article has shown me it’s not as bad as it seems.

Hi Steve,

It’s not really the Birmingham Defense, since I am playing 2… c5 instead of 2 … b5. I’m calling it the San Jose Defense. If you want to see more of my games with this opening go here:

http://www.cob.sjsu.edu/splane_m/chess/SanJoseDefense.htm

{ 1 trackback }