I’ve had a couple of days off from translating Sergey Shipov’s commentary on the Dortmund tournament, while Colin McGourty has ably translated rounds 5 and 6. You can read his translations at www.chessintranslation.com or follow the original commentary (in Russian) at www.crestbook.com. The Crestbook website has a Javascript board so that you can play through the moves of the game and also the sidelines.

The most surprising thing that happened since my last post is that Le Quang Liem, the Vietnamese junior who is playing his first super-GM tournament, has come to life. You might remember that Shipov was disappointed by Le’s play in round three, which featured a couple of tactical oversights and generally not making the most of his position against Mamedyarov. But in round four he turned his tournament around in a big way, with an upset over tournament leader Ruslan Ponomariov. He followed that up with a win against Peter Leko and a draw from a position of strength against Kramnik.

The game Le-Ponomariov was very interesting, and probably the most important game of the tournament so far, because if Ponomariov had won (or even drawn) he would have a commanding lead. Instead, it is still very much up for grabs, with Ponomariov, Mamedyarov, Le, and Kramnik all having a chance to win. The interesting thing about this game is that both of Ponamariov’s worst blunders involved moving the same piece — the h-pawn! See if you can figure out what is wrong with the two following moves.

Here, in a topical position from the Gruenfeld Defense, Ponomariov played 18. … h5, gaining space and threatening to trap White’s bishop with 19. … h4. What is wrong with this move?

Many moves later, Ponomariov is down a pawn but has managed to trade into a bishops of opposite colors endgame, where he might have a chance to draw. Here, though, he plays 31. …h4, probably thinking that White will eventually have to play g3 and he will then trade pawns on g3. Pawn trades make the defense easier. Not only that, Ponomariov was probably thinking that his pawn didn’t have much of a future on h5 anyway.

All of these are good reasons, and I would have been tempted to play 31. … h4, too. Nevertheless, Alexander Shershkov, who commented the game on Crestbook, says Black is clearly lost after this move. What is wrong with it?

Answers:

18. … h5? allows the tactical resource 19. Nxg6! Nxg6 20. Bd6! This followup is surely what Ponomariov missed. If Black takes the bishop with 20. … Qxd6, then he loses the queen to the discovered attack 21. Bxf7+! Instead Ponomariov played 20. … Qe8 21. Qxe8+ Rxe8, but now the bishop on b7 is en prise: 22. Bxb7 and White has won a pawn. The problem with … h5, of course, was that Black needed the pawn on h7 to protect g6. This was pretty hard to see because it looks as if the pawn has three defenders, so what’s the harm in moving one of them?

It’s kind of nice to see that even one of the world’s leading players, who is actually having an outstanding tournament so far, could still overlook something like this.

31. … h4? is a completely different kind of mistake — not tactical, but strategic. The key point here was that Ponomariov had to anticipate that White’s plan is to play f4 and e5. Why is this a big deal? Because in opposite-color bishop endgames, fighting for the squares that your opponent’s bishop controls is of paramount importance. White’s pawns can always advance safely to light squares, but advancing safely to the dark squares f4 and e5 is a major accomplishment for him. This will enable his king to reach the powerful square e4, after which f5, Kd5, Kd6, Kd7, and e6 are going to be hard for Black to stop. Also, bishop sacrifices at f7 are not out of the realm of possibility.

On the other hand, if Black can prevent the advance e5, then White’s king remains bottled up behind the pawn at e4. If White plays f4-f5 (a bad idea) then it would be a complete draw.

So Black’s first item of business is to unpin his f-pawn with 31. … Kg7, so that after 32. f4 he can play 32. … f6. Certainly the game is not over yet, but White will have a difficult time achieving the key break e4-e5. As I said, in opposite-color bishop endgames, the hard thing is always getting your pawns safely onto and past the squares controlled by your opponent’s bishop.

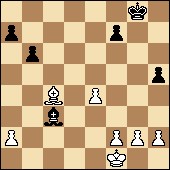

The game actually continued 31. … h4? 32. f4 Kg7 33. e5! As Shershkov writes, “Now it’s all over. Black cannot prevent the formation of two connected passed pawns.” Now Ponomariov played 33. … f6, but it was too late. Le played 34. ef+ Kxf6 35. g3 Kf5 36. Bd3+ Ke6 (diagram)

and here, as promised, after 37. Kg2 hg 38. hg we have a position where White has two connected passed pawns.

Shershkov’s comment was illuminating to me because if you took the queenside pawns off the board, the position would be a dead draw. The connected passed pawns would be no big deal because Black can blockade them if they are on white squares, or sacrifice his bishop for them if they are on dark squares. But with the queenside pawns on the board, it is a win for White (even though Black has a 2-1 advantage over there at the moment). After forcing Black to sac his bishop for the two kingside pawns, White will bring his king to the queenside, force Black’s king away from the defense of those pawns, and win both of them. At that point he will be left with a passed a-pawn, and the game will be won because the queening square of the a-pawn is a light square! If in the third diagram above we just switched the White and Black bishops, so the White bishop was on c3 and the Black bishop was on d3, then the game would be a draw!

Shershkov’s comment made me realized that I have mis-learned something about these endgames. Because two connected passed pawns do not win if they are the only pawns left on the board, I had assumed that connected passed pawns are not that big a deal in bishops of opposite color endgames. But Shershkov is saying that they are. Connected passed pawns are still a mighty force, the strongest kind of passed pawns there are. It’s just that White also needs a pawn somewhere else on the board, to “mop up” after the connected passers have done their damage.

Meanwhile, for Ponomariov the lesson seems clear. Don’t touch that h-pawn!

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

thanks for the comments on bishop opposite color in relation to connected passed pawns. Very instructive.