One of my positions in the recent Chicago Open could have reached a position that I think only a computer could play correctly. Yesterday I got together with four friends — Yves Tan, Gjon Feinstein, Cailen Melville, and Thadeus Frei — and we spent at least an hour going over the game, and we didn’t even get close to finding the right way for me to play the attack or the correct evaluation of the position. Once upon a time, people like Garry Kasparov said that computers would never play as well as humans because they lacked creativity or imagination. But now I think the exact opposite is true. We can’t play as well as computers because we lack imagination.

Here is the position where all the fun starts. It’s from my fourth-round game against Gavin McClanahan (which I previously discussed in this post).

In this position I played 21. hg, and then my opponent surprised me by recapturing, 21. … fg, which led to a clearly inferior position for him, as his kingside was ripped open and his extra pawn was meaningless because it came in the form of two sets of weak doubled pawns. I was surprised also because he played the recapture fairly quickly; I guess he had made up his mind before I even made my move.

The question is, what happens if after 21. hg Black instead plays 21. … f6, with the idea of either chasing away the knight and winning the g-pawn with a much more solid pawn formation, or else trying to trap the knight on f7?

Of course my plan was to play 22. Nf7, after which the moves 22. … Rxh1 23. Rxh1 Kxg6 are obvious. But in the ensuing position, I had no idea whether I could actually save my knight — let alone recover my sacrificed pawn.

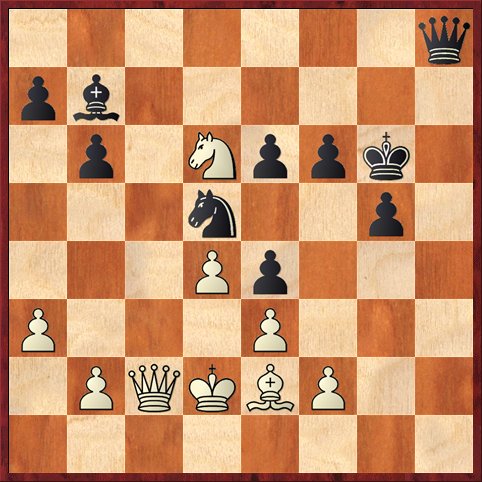

Position after 23. … Kxg6 (analysis)

Take a good long time to think about this position and figure out what you would do as White, and what your evaluation of the position is. As I said, five of us working together yesterday didn’t even come close to seeing the right idea.

The moves that we looked at were things like 24. Bh5+ and 24. Rh6+, and the conclusion we reached was that White has a lot of tricks, but if Black plays carefully White will lose material and not get enough compensation for it. Psychologically, I think the reason for our mistake was that humans think that if a piece is in danger, we have to do something about it.

However, the computer does not have these preconceptions. In the position above, Rybka 3 comes up with the stunning “quiet move” 24. Qc2!! Yes, that’s right! Even though the knight on f7 is attacked two different ways, White doesn’t need to do a darned thing to protect it. Both captures, 24. … Kxf7 or 24. … Qxf7, lose the queen to a skewer.Meanwhile, White calmly threatens to play 25. Qxe4+. This is huge, because in our analysis orgy yesterday the one problem we kept running up against in playing White’s attack was the fact that White’s queen has trouble participating.

How could a human find a move like 24. Qc2? I think that the first step is to realize the knight is not hanging. The second step is to ask yourself which is your worst-placed piece, and look for something effective to do with it.

But we’re not done yet. Black has a couple ways to defend the e-pawn. First, if he plays 24. … f5, now we play 25. Qd1! The knight is still taboo, and now we are planning ultra-nasty stuff like 26. Nxg5! If 25. … g4, then we sac the bishop instead: 26. Bxg4! and Black’s fortress is crumbling.

Second, if he plays 24. … Nc7, then we can follow up with 25. f4! the pawn on e4 is pinned, and now once again we are putting pressure on his sensitive point, g5. Note how the charmed knight is functioning as an attacker. Rybka gives White a greater than one pawn advantage in this position.

I think that most humans would just crumble here as Black. But Rybka suggests one other defensive possibility — 24. … Rg8!

Position after 24. … Rg8 (analysis).

The point of this move is to get serious about winning the knight on f7. Black plans 25. … Kxf7 26. Rh7+ Rg7, and there is no way for White to break through.

Now what would you do as White? Even with the advantage of knowing that the computer liked White’s position, I still couldn’t find the right continuation.

The answer is 25. Nh6! I looked at this and discarded it because I thought after 25. … Rh8, the knight still hangs. 26. Qxe4+ looked interesting, but Black refutes it with 26. … Kg7! (Not 26. … f5? 27. Nxf5!) 27. Bd3 f5! (Now Black is ready for this move, because he has defended the rook on h8) 28. Qe5+ Qf6! Black has plugged all the leaks, and now White has to give up the knight.

But the correct move is much simpler: after 25. Nh6! Rh8, White plays 26. Nf5! right away. Both Black’s queen and rook are hanging. After 26. … Qd8 27. Rxh8 Qxh8 it seems Black may still be okay — he is still a pawn up, and his king has almost weathered the storm. Alas, the rude awakening comes with 28. Nd6!

Both the bishop on b7 and the pawn on e4 are hanging. Once White plays Qxe4+ and Qxe6, it will be time for Black to run up the white flag.

Sometimes analysis sessions like this one with the computer can be depressing, because you end up feeling as if you really don’t know how to play chess. But I look on it as an opportunity to stretch and strengthen your imagination. Positions with a trapped piece are always especially challenging. I think that the biggest lessons for me were these:

- Just because a piece is attacked twice, you don’t necessarily have to move it or even attempt to rescue it!

- Even in a highly tactical position, strategic considerations can come into play. Ask yourself what piece is not participating in your attack, and see if you can find a way to activate it.

- Although you should begin your analysis with captures and checks, you should not end it with them. Don’t forget to look for quiet moves. (Here, 24. Qc2 and 25. Nh6.)

- Don’t forget your basic tactical motifs. In this game, skewers and discovered attacks were huge.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

My first thought was 21 hg f6 22 f3 to forget about the trapped Knight and open up lines. GM John Nunn was talking about Queens when he said they often grab a wayward pawn and try to retreat back to the center when they should stay where they are after they grab the pawn and create trouble there. Bloom where you’re planted. I once lost to a talented 10 year old because I thought a critical attacking piece was “overextended” and panicked when I should have been piling on more pressure. That game traumatized me so much that it became almost pyschologically impossible for me to retreat any attacking piece thereafter. Computer generated or not I thought it was a beautiful, instructive piece of analysis.

One of my Chess rules is that 90% of tactical puzzles can be solved by one thought – remove the obstacles between the White Queen and the Black King.