First, let me say that the title of this post is not literally true. However, it’s something that I like to tell my students, and it’s not as far-fetched as it seems. It’s intended to correct a very harmful mindset that starts affecting players as soon as they learn the values of the pieces.

According to the standard piece value system (knight = 3 pawns, bishop = 3 pawns, rook = 5 pawns) there are lots of trades that are supposed to be even. Knight for bishop. Bishop for bishop. Rook for rook. Rook and pawn for two pieces. Knight for three pawns. But they seldom are completely even. Especially in the case of minor-piece trades, I often see beginning or intermediate players trading very happily, as if this were checkers and trades were compulsory.

Chess isn’t checkers. And deciding whether to trade or not is one of the most important decisions that players face on a regular basis. A player who regularly trades pieces, even when it is beneficial to the opponent, is a player who will not do well when he starts playing more sophisticated opponents.

Because I’ve been playing lots of games against my student Atlee, I’ve been thinking about this phenomenon a lot. In our most recent game, there were two interesting positions where the decision “to trade or not to trade?” arose. In the first case, Atlee made the wrong decision, and it led him into a very passive position. After the game he had no idea what the root cause of his strategic disadvantage was.

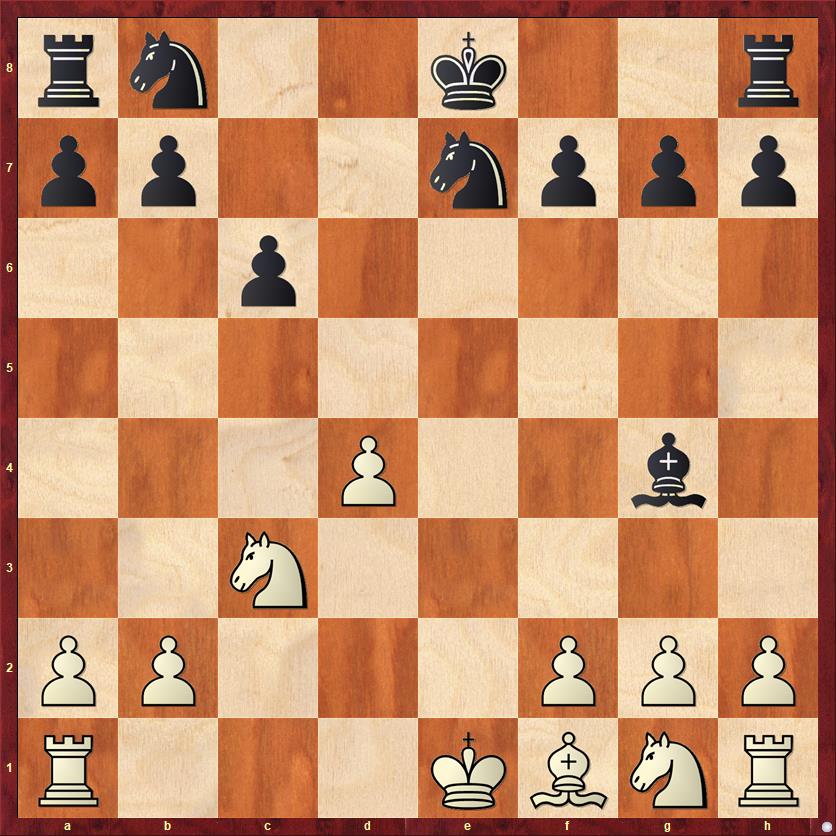

Atlee was White and I was Black, and after the opening moves 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. ed (Did I mention that Atlee likes trades?) ed 4. c4 Nf6 5. Nc3 Be7 6. Bg5 c6 7. cd Nxd5 8. Bxe7 Qxe7+ 9. Qe2 Bg4 10. Qxe7+ Nxe7 we reached the position in the diagram.

FEN: rn2k2r/pp2nppp/2p5/8/3P2b1/2N5/PP3PPP/R3KBNR w KQkq – 0 11

We’ve had several trades already, which I think were not bad for White. I would describe his opening so far as unambitious but solid. Perhaps it was even a good variation to play, given that I’m rated about 700 points above him. But now he played a move that surprised me, because I would never consider playing it against anyone.

11. Be2?! …

Why is this move so bad, compared to the other trades that have already happened, and what should White have played?

I am sure that Atlee considered the possible trade of bishops on e2 to be “an even trade,” neither bad nor good. To understand why it’s bad, you have to think about how the trade affects everything else in the position.

First key point: White has one big weakness, the isolated pawn on d4. Of course, isolated queen pawn (IQP) positions are a staple of chess, and people voluntarily accept this kind of weakness all the time. But there has to be a reason for it. If you have an IQP, you usually need to seek compensation for that weakness in the form of active pieces. This already tells us that White should not just trade willy-nilly. We have to ask, is there an active future for my bishop? And what about Black’s bishop?

Second key point: One of the easiest ways to handle an IQP position is simply to liquidate it. If White succeeds in playing d4-d5 and trading off the d-pawn, he could not possibly be worse. The worst that could possibly happen is that we would quickly trade down to a dead-drawn endgame, and in view of our 700-point rating difference, Atlee would probably not mind that.

So White’s bishop should go to a square where it supports the d4-d5 pawn break. This immediately tells us that 11. Bc4 is probably the right move. In addition, 11. Bc4 takes away the e6 square from Black’s bishop, and thus makes it even harder for Black to contest the d4-d5 break. Black’s bishop will probably hang out on g4 for a while, but that is a strange square where it’s keeping White’s rooks out of d1 but not doing much else. Sooner or later, White will probably chase it away with h3 or f3, but White does not need to be in a rush to play those moves. (Especially f3, which creates some weaknesses.)

Even the computer agrees with me. According to Fritz, the position after 11. Bc4 is -0.03 for White, but the position after 11. Be2 is -0.23. If anything, I think that this is an underestimate of the true damage.

11. … Bxe2 12. Nxe2 Na6!

Here is another concrete reason why the exchange of bishops was a mistake for White. Previously my knight could not go to a6 because of Bxa6 ruining my pawn structure. Now it easily comes to a6 and from there goes to c7, with a Nimzovichian clamp on the d-pawn.

13. O-O?! …

A better try was 13. O-O-O, which gains a tempo compared to the game, and would be the only real argument in favor of playing 11. Be2. However, I would also say that if a natural move like 13. O-O is wrong, this is already a sign that White has gone astray.

13. … O-O-O

Black’s strategy over the next several moves is dead simple. Pile up pressure against d4, but make sure that you don’t overdo it and allow d4-d5. Also, set up a pin on the d-file. I could have played … c5 earlier than I did, but I was in a very Nimzovichian frame of mind. Restrain, restrain, restrain, and only attack when your threats become overwhelming.

14. Rad1 Rd7 15. Rd2 Rhd8 16. Rfd1 Nc7 17. Rd3 b6

See comments above. I thought about 17. … c5 here, but I didn’t yet see a way to force a win of the d-pawn, and there’s a danger that he might be able to push his pawn to d5, or else break the pin with Rd2, Kf1, and Ke1, and then liquidate his weak d-pawn. For me, there is no problem with playing waiting moves that improve my position. The move 17. … b6 keeps his knight out of c5 and also prepares … Kb7, avoiding any possible pins or unpleasantness on the c-file.

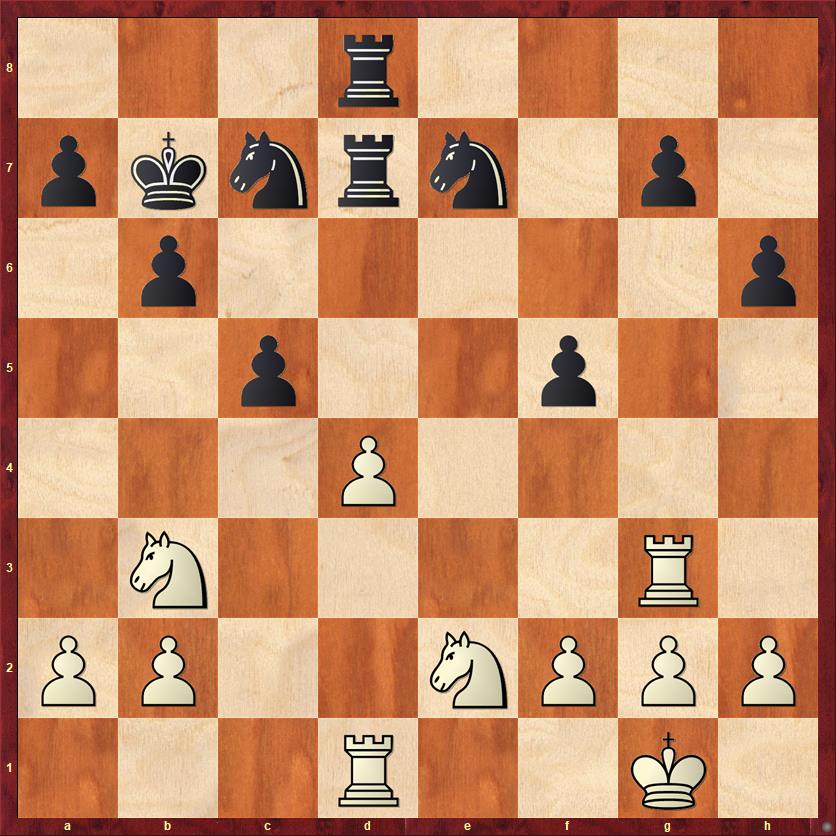

18. Ne4 h6 19. Rf3 f5 20. Nd2 c5 21. Nb3 Kb7 22. Rg3 …

FEN: 3r4/pknrn1p1/1p5p/2p2p2/3P4/1N4R1/PP2NPPP/3R2K1 b – – 0 22

Compare this position with the previous diagram to see the long-lasting consequences of White’s decision to trade bishops on move 11. Three of white’s four pieces are tied to defensive positions, protecting d4. The other piece, the rook on g3, is sort of in limbo, unable to come back to d3 because of the pawn fork … c5-c4. White can’t trade the d-pawn because of the pin on the d-file, and he can’t push to d5 because he has inadequate force to do so.

This is exactly the right moment for Black to exit Nimzovich mode and mop up with 22. … Nc6, which forces the win of a pawn. Unfortunately, I was having too much fun playing cat-and-mouse and now played a mistake that muddies the position quite a bit.

22. … g5? 23. Rh3! Rd6 24. Rc1? …

Right idea, wrong square. White wants to break the pin on the d-file, but this doesn’t do it. If he had played 24. Re1!, then we would have had a real battle again.

24. … Nc6!

As it turns out, White’s d4 pawn is still pinned — not against a piece, but against a back-rank mating threat. Black wins a pawn.

25. f4 cd 26. fg hg 27. Rd1 Ne6 28. Nbc1 Ne5 29. Nd3 …

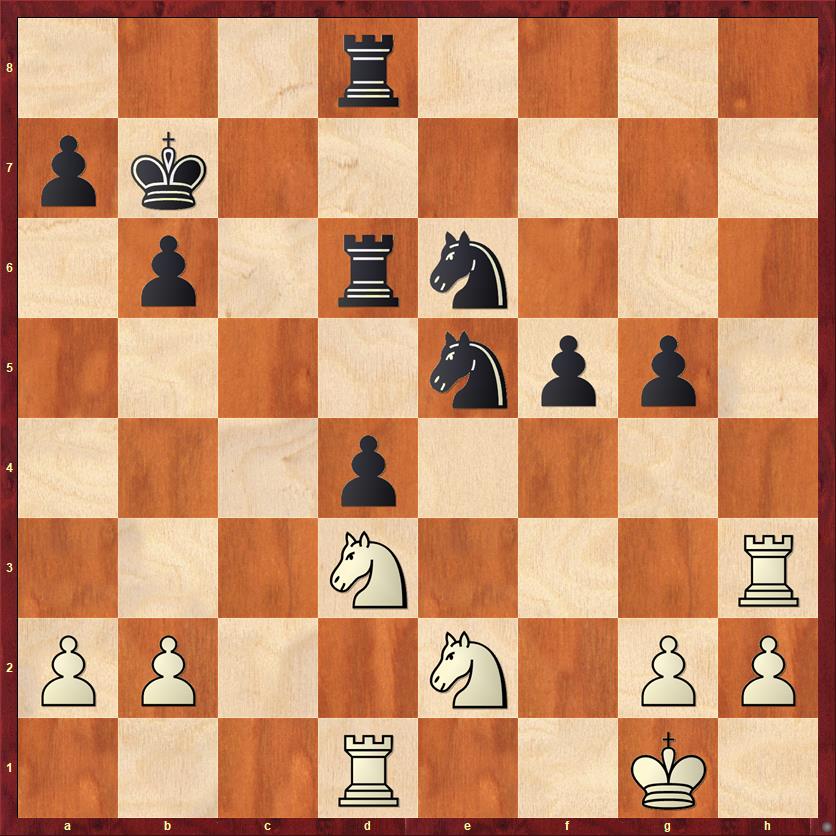

FEN: 3r4/pk6/1p1rn3/4npp1/3p4/3N3R/PP2N1PP/3R2K1 b – – 0 29

This was the second interesting trade-or-don’t-trade decision of the game. It’s not as clear-cut as the first, but for that reason it may be more instructive for advanced readers.

First thing to note is that Black is a pawn up. So you might be inclined to trade pieces as a knee-jerk reaction. In fact, that was my original intention in this position. Who can argue with a pawn-up and probably winning endgame?

But as I looked at the position after 29. … Nxd3 30. R3xd3, some doubts started creeping in. What concrete plan do I have for advancing my d-pawn? It looks as if all my pieces are tied down to defense, and as soon as I play a move like 30. … Nc5, trying to push his rook back, then I just lose the d-pawn. The only way out of this conundrum seems to be bringing up the king to c5, but as soon as I do that, his rook will check me on c1 and send my king scurrying back again. In short, I didn’t see a plan for Black. Without a plan, even if you’re a pawn up, you can’t count on winning.

So then I started asking myself, “Why should I trade on d3, anyway?” At present his rooks are uncoordinated. Why should I gift-wrap a tempo so that he can link them up again in a battery on the d-file? Also, I asked myself, “Which is a better piece, my knight or his knight?” His knight on d3 is a nice blockader but makes no threats. My knight can come to e3, where it dominates the position and — by the way — reinstates the possibility of some back-rank mating threats.

So I concluded that the exchange on d3 was not an even trade but an unfavorable one, and I chose 29. … Ng4. Basically, Black is saying that there is no rush to go into the endgame, because there is a high probability that Black can milk a bigger advantage out of the middlegame.

I regret to say that the computer does not agree with me. Fritz rates the two moves practically the same: +1.52 pawns for Black after 29. … Ng4, +1.49 pawns for Black after 29. … Nxd3. I think the main reason is that it does some very concrete analysis, and in particular after 29. … Nxd3 it spots ways for Black to make progress that I didn’t see. After 30. Rxd3 it recomments 30. … a5! Black will try to force White to commit himself to change the pawn formation on the queenside. If White plays b2-b3 at some point, then Black has a great entry square on c3 (and yes, he might be able to sacrifice the exchange there very effectively). If White plays a2-a3, Black can play … a4, clamping down on the queenside, and then possibly bring a rook to c4. Then Black’s king can come to c5 without being chased away by rook checks.

This was all really interesting and educational for me, because it shows the potential for seemingly unimportant pawn moves on the flanks to make a big difference to the action in the center. So I’m willing to admit that my 29. … Ng4 was not an improvement over 29. … Nxd3. But an even more important point, for most of us, is that Black should not trade knights as a knee-jerk reflex. He should trade only if he has a concrete plan to improve his position.

Anyway, after 29. … Ng4 the game ended very quickly:

30. Rf3 Ne3 31. Rd2 g4 32. Rf2 Ng5! 33. Ng3 Ne4 34. Nxe4 fe

Now Black’s connected and passed pawns should be overwhelming. In this hopeless position, Atlee forgot about my main threat and played 35. Rf4? ed 36. White resigns.

As with so many other things in chess, I think that it was Mike Splane who really woke me up to the fact that so many trades that appear to be routine are anything but. Even when a trade is not being offered, you should constantly think about what trades would be beneficial for you and what trades would be harmful. But a good way to work up to this level of strategy is at least to think more carefully about trades at the time that they are offered.

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

Hallo Dana.

You should have made some remarks about 4. c4.

It is a quite uncommon move, transforming a French Exchange setup into an QGD position with an isolated queen’s pawn (IQP).

The first game in master play seems to have been Tartakower – Rubinstein, St. Petersburg 1909 (by transposition), later ending drawn (1/2, 41).

The characteristic feature of this kind of position is that the Black pawn is on the c-file, often on c6, instead of being placed on e6 as in QGD- or Nimzo-Indian positions.

This is taking only strategic positional evaluations in account better for Black than the pawn position on e6, but one disdvantage is that the (weak) point f7 can get easilier attacked, e.g. by a white bishop on c4 and a knight on e5.

The kind of position in the first diagram is known for long time. See Chajes – Capablanca 1918 after White playing 22. cxd4. Capablanca later wins a instructive endgame (0:1, 81). A even wider known example – at least in Europe resulting from an extensive analysis by Keres himself – is Averbakh [spelling also Awerbach] – Keres 1950

after 22. cxd4 or after 27. Rxe4. Despite hard defence (and later White setting up a clever trap) Keres wins after 58 moves.

4.c4 underwent a modest revival around the 1990-s. The resulting position is not dissimilar to the ones that arise in the Old Main Giuoco Piano line (5.d4 exd4 6.cxd4 Bb4+ 7.Bd2 Bxd2+) and the White’s potential in that line is best revealed, probably, in Schiffers – Harmonist, Frankfurt, 1887, whereas the staple Black’s play is probably in Khavin – Kholmov, Riga, 1954.

That line, unfortunately, has now been proven as a forced draw at best, though.

Regarding the third diagram and the question to trade or not to trade (and taking into account also Fritz’s evaluation) this position must offer Black a great, probably winning advantage as he is a pawn up and the plus pawn is a free pawn threatening to advance further.

The winning strategy in the case of trading the knights 29. ….Nxd3 30. Rxd3 is to create a second weakness for the defender (concept of the two weaknesses). This could mean beside the good option 30 …a5 (advocated by Fritz) a more human approach would be 30. …g4 with the intention to fix White’s kingside pawns, especially the h-pawn, and attack them with a rook (presumly from h8, h7 or h6), but this would give a good square to White’s remaining knight. So 30. …f4 would have a good choice for humans.

These are all good points, and I especially like the fact that you bring up the principle of the two weaknesses. That explains why Black needs to look for a way to create a weakness either on the queenside or the kingside, using pawn moves like 30. … a5.

Thanks for highlighting how important the relative value of the pieces are and the significance of all piece trades, which is something a lot of people at the Class level don’t pay attention to.