As I mentioned before, I’ve been playing a training game each week with one of my students from the Aptos Library Chess Club, Atlee, who is about a 1500-strength player (I’m guessing). The games follow an interesting pattern. I win, I teach Atlee a lesson, then I come home and go over the game on the computer and the computer teaches me a different lesson! It’s interesting that there can be two different truths, or two different levels of truth, about the same game.

Dana – Atlee

1. d4 d5 2. Bf4 Nc6

I have not figured out how to cure Atlee of the beginner habit of always developing his knights on c6 and f6 (if he can), and always developing his bishops on c5 and f5 (if he can). I’m not even sure that it’s such a bad habit. At the 1500 level there’s a lot to be said for just getting your pieces out. In fact, Atlee’s troubles in this game come from the fact that he doesn’t stick to that script and starts making a lot of pawn moves.

3. e3 Bf5 4. Bb5 a6 5. Bxc6+ bc 6. Nf3 e6 7. O-O c5?

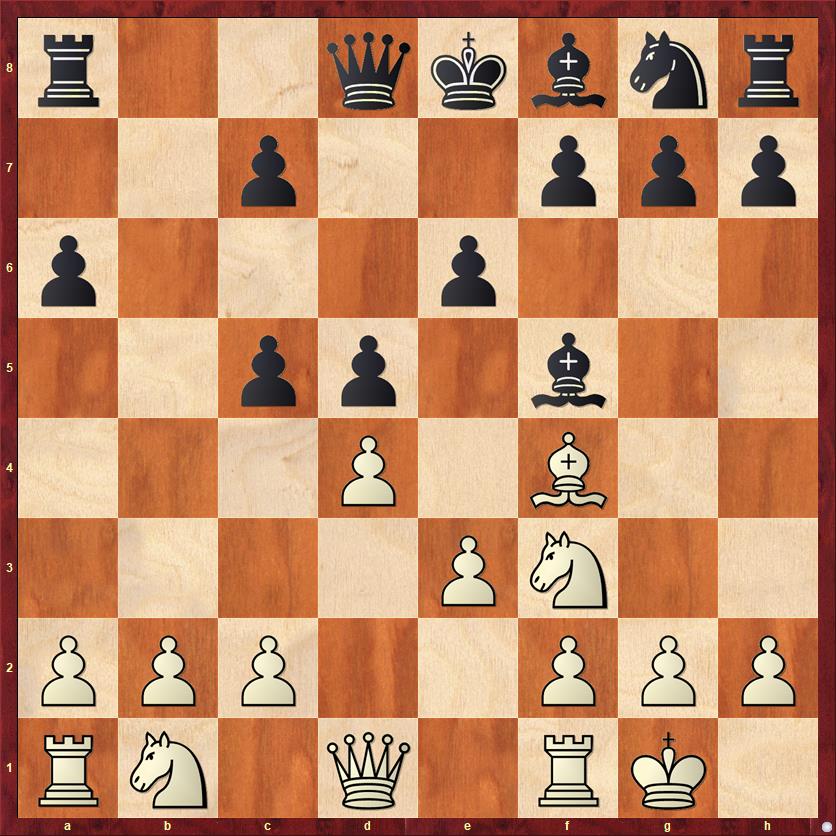

FEN: r2qkbnr/2p2ppp/p3p3/2pp1b2/3P1B2/4PN2/PPP2PPP/RN1Q1RK1 w kq – 0 8

I knew instinctively when Atlee played 7. … c5 that it was not a good move. But for him, it seemed like a natural move. He wanted to eliminate his weakness (the doubled pawns) before I had a chance to clamp down on it. Perhaps, as I mentioned above, he also wanted to develop his bishop to c5 after 8. cd Bxc5.

There are two things he’s missing that contributed to his mistake. One is a sense of danger. He’s behind in development, so the last thing he should do is open the position up with pawn moves. The open diagonal a4-e8, aimed at his king, should ring some alarm bells, particularly because his bishop is no longer in a position to defend the weak white squares on the queenside. For these reasons, I think Black should play … Bd6 and … Ne7, developing his pieces and defending c6.

The second thing Atlee is missing is an accurate sense of priorities. What’s more important here for Black, developing his pieces or repairing his pawn structure? It seemed obvious to me that Atlee’s choice was wrong. And this is a common thing when I talk with beginning players about their games: they often focus on one particular threat or plan or weakness that is far from being the most important thing about the position.

But you can say the same thing about me! So the lesson may be that there is no level of chess where you will have a perfect understanding of priorities. It is something that you can work to improve at any level.

8. c4! cd?

Going even farther down the wrong path. Black should look at White’s move and ask himself, “Why did White make this move? What does he want to do?” Then it should be obvious that White wants to bring his queen to a4, and Black should take immediate action to develop and defend his light squares, for example with 8. … Nf6. Instead he plays a non-developing pawn move.

9. Ne5?! …

Ironically, I was proud of this move! It’s Dana Mackenzie chess — fighting for the initiative and not worrying too much about whether I’m a pawn up or down. Nevertheless, the computer says that the simple, obvious 9. Nxd4 is better. Why? One reason is that my knight is not very stable on e5, and if it goes to c6 then Black can pin it against my queen. Also, I did not properly appreciate lines like 9. Nxd4 Bg6 10. Qa4+ Qd7 11. Qxd7+ Kxd7, where the queens get traded off early. It looked to me as if my advantage was minimal. But after, say, 12. cd ed 13. Nc3 c6 14. Na4, Black’s position completely collapses!

Perhaps this is a flaw in my chess: overthinking and playing baroque, complicated moves when a simple one will do better. See move 16 for a case where I resisted this impulse.

9. … Bd6 10. Qa4+ Kf8

Now I thought I had a huge advantage. But I do have to think about what to do with my knight. The move 11. Nd7+ is superficially attractive, but after 11. … Ke7 12. Bxd6+ cd my knight is trapped!

11. ed Bxe5

Atlee correctly feels that the knight is a thorn in his side, but he comes up with the wrong thing to do about it. The computer says that the position is equal after 11. … f6! This really surprised me, but the reason is that after 12. Nc6 Qe8 I have a bunch of weak pieces — the pinned knight on c6, the bishop on f4 — and this forces me to make positional concessions. For example, 13. Bxd6+ cd 14. Nc3 dc 15. Qxc4 Rc8 16. d5 Ne7 and the knight on c6 comes under heavy fire.

In this line it’s remarkable how quickly the seemingly powerful knight on e5 turned into a liability. I greatly underestimated Black’s play after 11. … f6. It looked like a desperate move to me, so I brushed it off as inconsequential. However, it’s actually a logical and good move that addresses a problem in Black’s position. I’m guilty of the same sort of knee-jerk thinking that I criticized Atlee for earlier.

12. Bxe5 Ne7

Here I was hoping that Atlee would fall into the trap 12. … Bd3?? 13. Qa3+. He didn’t, but the variation alerted me to the fact that a3 is an excellent square for my queen.

13. Rc1 c6 14. Nd2 Qb6?!

I don’t blame Atlee for wanting to play actively, but again he shows a pattern of prioritizing other things (such as winning the b2 pawn) over the safety of his king.

15. Qa3! …

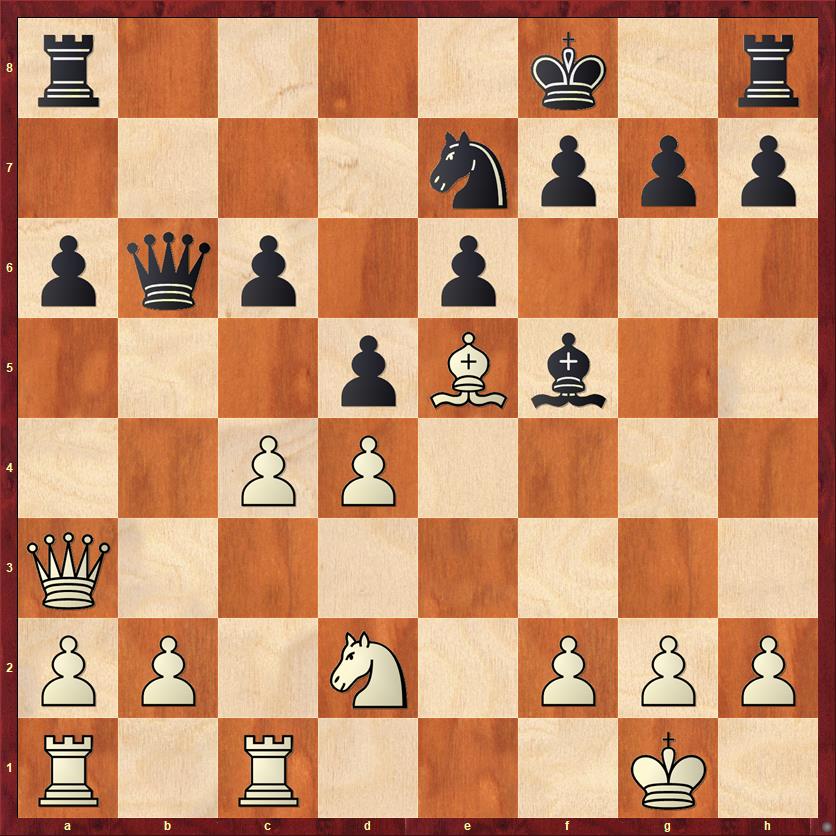

FEN: r4k1r/4nppp/pqp1p3/3pBb2/2PP4/Q7/PP1N1PPP/R1R3K1 b – – 0 15

I really loved putting my queen on this square because it does so many things. It eyes the king on f8 and pins the knight on e7, so that Black’s king can’t run away. It sets up a queen-bishop battery on the a6-f8 diagonal. Also, it’s very easy now to switch the queen to the kingside if I should decide to pursue a kingside attack. Oh, and by the way, the queen also protects b2.

I’m not sure if this occurred to me consciously during the game, but at least the position reminded me subconsciously of the eighth game of the Carlsen-Nepomniachtchi match:

FEN: 5k2/p2b1pp1/2p2q1r/1p6/2BP3p/Q6P/PP3PP1/4R1K1 b – – 0 22

Nepo had overlooked Carlsen’s move 22. Qa3+, or more likely he overlooked one of the tactical points afterwards. I felt that it was a little unfair that the commentators called it a “one-move blunder” by Nepo, because there are several things you have to notice. One is that after 22. … Qd6 23. Qxa7 White is threatening mate, so Black doesn’t have time to capture the bishop on c4. Another is that after 22. … Kg8 23. Qxa7 Bxh3! White wins the battle of the kamikaze bishops because White can collect another pawn with 24. Qxf7+!

Anyway, the pattern imprinted itself on my brain. Black king on f8. White queen goes to a3. Back-rank mate threats. All of those things happened again in my game against Atlee. Now, back to diagram two.

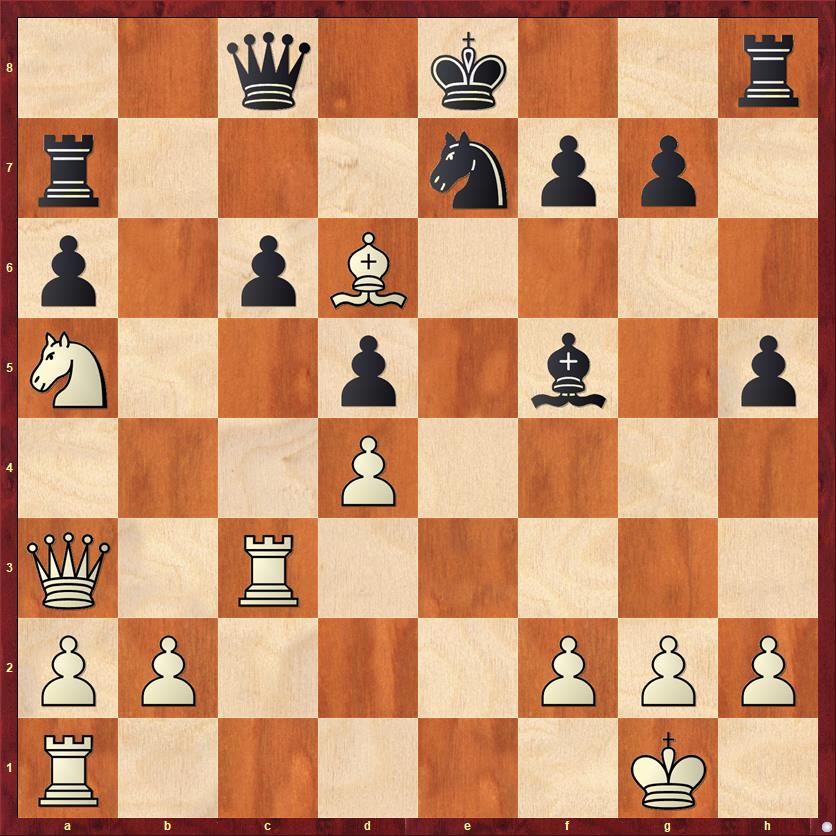

15. … Ra7

Now I was sorely tempted to play 16. g4?!, with the idea of swinging the queen over to the kingside after 16. … Bxg4 17. Qg3. Fortunately, I talked myself out of it. There is absolutely no need to play such a wild, coffeehouse-style move in a strategically won position. Then I asked myself, what is wrong with Black’s move, … Ra7? What weakness does it create that wasn’t there before? I realized that there was nothing defending Black’s back rank. This gives me the opportunity to play

16. cd! …

Black would like to recapture with the c-pawn, but unfortunately 16. … cd?? 17. Rc8+ is followed by mate on the next move. So he has to recapture with the e-pawn, which is bad for two reasons: it opens the e-file, and it leaves the c6 pawn backward on a half-open file.

16. … ed 17. Bd6 …

Besides setting up a battery on the a3-f8 diagonal, this also threatens a skewer with Bc5 — another unfortunate consequence (for Black) of Black’s 15th move.

17. … Qb7 18. Nb3 …

Of course, I could have won a pawn with 18. Bxe7+ Qxe7 19. Qxe7+ Kxe7 20. Rxc6, but that solves all of Black’s problems and trades down into an endgame. I wanted to keep the pieces on the board so that when my breakthrough comes — as it inevitably will — Black will be completely annihilated.

18. … Qc8 19. Na5 Ke8 20. Rc3 …

Again I could take on e7 and then c6, but why rush? I’m having fun. I want to get all of my pieces into the attack, and in addition I have a sneaky threat. I had a hard time even finding a decent move for Atlee to try. But he kept his cool and eventually found a plausible idea.

20. … h5

Planning to activate his remaining rook via h6. This does force me to think about speeding up my attack a little bit. Fortunately, I had an idea already prepared.

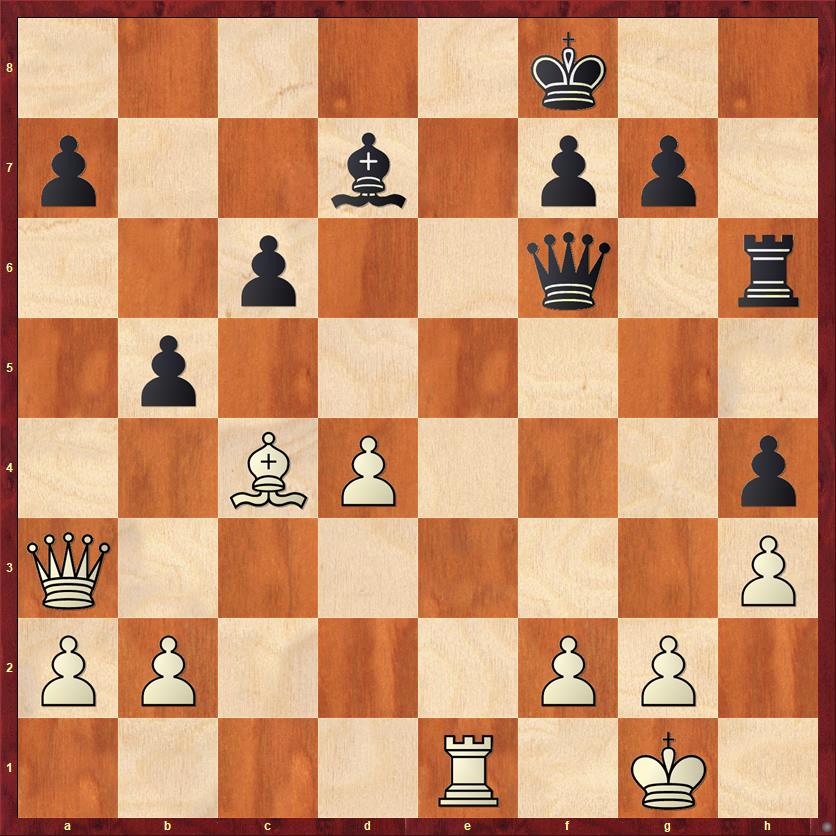

FEN: 2q1k2r/r3npp1/p1pB4/N2p1b1p/3P4/Q1R5/PP3PPP/R5K1 w – – 0 21

21. Rb3 …

Threatening to skewer the queen and king with 22. Rb8. Once again it’s the back-rank weakness that kills Black. There are only two possible defenses. 21. … Qd7 loses a rook to 22. Bxe7 Qxe7 23. Rb8+, so Atlee chooses the other one.

21. … Qe6 22. Re3 …

Changing directions! The one way for White to blow the game would be to continue as in the previous note, 22. Bxe7 Rxe7 23. Rb8+ Kd7 24. Rxh8 Qe1+! and Black mates next move. I would love to see Atlee win a game this way, but not against me!

22. … Qf6 23. Nxc6 Black resigns

I feel a little bit guilty about continuing to show you my training games with Atlee, because I understand that he is completely overmatched. But I hope that there is some instructive value in his errors (and my errors!). Also, I really liked the way I was able to keep my initiative going by continually changing the focus of my attack. First it was the a4-e8 diagonal. Then the a3-f8 diagonal. Then the c-file, and the back rank. Then the g1-a7 diagonal. Then the b-file, and the back rank again. Then the e-file, and the c6-pawn, and finally the pinned knight on e7 that had been a problem for Black all along. Black just wasn’t able to plug all the holes in his position, which started to spring leaks all the way back on move 7.

And finally, I enjoyed the chance to apply the “Carlsen rule” in practice: when your opponent puts his king on f8, put your queen on a3. It always works! 😉