In 2007, I had my first and only slight brush with celebrity, when I appeared on national television for the first time. I was interviewed for a new television show called “The Universe,” which aired for four or five season on the History Channel. In the first season they had an episode that was, appropriately enough, called “The Moon.”

The director assigned to that episode, Tony Long, went to the library to read about the moon, and there he discovered my book The Big Splat, or How Our Moon Came to Be. He liked it enough to invite me to be one of the “talking heads” on the show. We recorded the interview in February 2007, on a beach in Malibu, or actually on a cliff above the beach. I had suggested filming on the beach because it would be a good visual when I talked about how the moon produces tides. But within ten minutes of our starting the interview, a big wave came up and nearly wiped out their expensive cameras, and after that Tony decided that the cliff would be a better idea.

The episode aired on June 26, and I held a viewing party with some of my friends. I was pleased and more than a little bit relieved at how it came out. I think that “The Moon” was one of their better episodes that season, in part because Tony essentially followed my script! The last 45 minutes of the episode followed the outline of The Big Splat. I had done him a big favor by writing that book. But he did me a favor, too. As I told my friends, “It was like watching the Hollywood version of my book!”

One of my science writer friends, who had actually produced some documentaries for TV, had an interesting perspective. “I think the History Channel will make money on this,” he said. He pointed out that aside from the graphics it was very inexpensive to produce, and they had gotten a lot of help for free, by interviewing me and the other scientists and getting me to do their fact-checking (and butt-saving). I said, “Well, they paid me $250 for the fact-checking.” He said, with a smile, “Like I said — free.”

The whole experience made me realize some things about the media universe. When I was invited to appear on the program, I thought, “Great! This will be a way to sell some more books!” But afterwards, I realized that I had it backwards. People don’t go on TV to sell books; it’s the opposite. People write books to audition for TV. Actors have other ways to audition, of course. But if you are a writer or an academic, writing a book is the way that you establish your credentials to appear on television.

For me, as a person who values words, this was a depressing thing to realize. But as a science communicator I could only be grateful for the opportunity that the History Channel gave me. Some simple numbers will show you why. In eighteen years, The Big Splat has sold just short of 8000 copies. If we assume that an equal number of people have read it in the library, that means maybe 16,000 people have learned about the giant impact theory through reading my book. Now compare that to the audience of the History Channel. Tony estimated that about a half million people would watch that episode of “The Universe.” So 500,000 people have learned about the giant impact theory by seeing me talk about it on TV.

The reason I got into this business was that I wanted to help explain science to the general public. The reason I wrote The Big Splat was that I wanted to explain to the public what scientific returns we had gotten from the Apollo moon missions, and what we have learned about the Moon since then. Both of these goals were accomplished much more by the TV show than the book.

And it was nice to get a small amount of public recognition. Now and then, after it aired, people would come up to me at chess tournaments and say, “I saw you on TV!” Or they would say, “I saw your article in Chess Life!” (My article about the David Pruess game came out in 2007.) Or they would even say, “I read your blog!”

Ah, yes, my blog. That was my other big chess news of 2007: it was the year I began the blog that you are reading right now. Actually I started two blogs, one about the Moon and one about chess, but this is the one that I truly felt passionate about and that attracted the best audience. Thank you to all the people who have sent me comments over the years! They are part of what keeps me going.

The first 36 years of my retrospective took place pre-blog, and so I’ve been writing mostly about games and events I had never written about before. But from here on, the remaining 14 years of my journey have all been covered here in real time. I hope that I won’t repeat myself too much. But even if I do repeat myself, I suspect that few people reading this blog now will remember what I wrote fourteen years ago. If I come across some really good posts from earlier in this blog, I might just re-post them with updates. We’ll see.

Anyway, today I will take my last opportunity to show you a game played before this blog existed. I mentioned the five Santa Cruz Cup tournaments that Eric Fingal organized from 2003 to 2008. The competition was incredibly intense, and it was never more intense than in the fourth cup, which finished in March 2007. That was the year that Juande Perea and I tied for first place.

As I mentioned last time, the Santa Cruz Cups had a “regular season” phase and a “playoff” phase. Once again, Jeff Mallett, Ilan Benjamin, Juande Perea and I qualified for the playoffs. In the semifinals, I defeated Ilan 1.5-0.5, and Juande defeated Jeff, 1.5-0.5. So Juande and I faced each other in the championship match.

The first game was a disaster. During the “regular season” phase of the tournament, I had experimented with Alekhine’s Defense (abandoning my usual 1. e4 e5 for the first time since the early 1980s!) and managed to draw with Juande. When I brought out the Alekhine again in the playoffs, Juande was ready and he completely outplayed me. So I was down 0-1, and the next game was a must-win for me.

What opening do you play if you have to win as White? For me, it was an easy choice: the King’s Gambit! The following game looks as if it came straight out of the nineteenth century.

Dana Mackenzie — Juande Perea, 3/11/2007

1. e4 e5 2. f4 ef 3. Bc4 Qh4+

This was no surprise to me. I had played many 25-minute games against Juande in chess club, and this was his usual response to the Bishop’s Gambit. But in a larger sense it is quite surprising, because Juande’s strength is his positional game. In a calm, quiet maneuvering game he would be a strong favorite against me, especially in a game where he effectively had draw odds!

Juande is the only master-strength player I have ever played against who likes 3. … Qh4+. Most people play 3. … d5 or 3. … Nf6, either of which would be much more consistent with Juande’s classical style.

4. Kf1 g5

King’s Gambit players love to see this move. If Black plays with maximum greed, then White gets a lead in development and targets to attack.

5. Nc3 c6 6. d4 d6 7. Nf3 Qh5 8. h4 h6 9. Kg1 g4

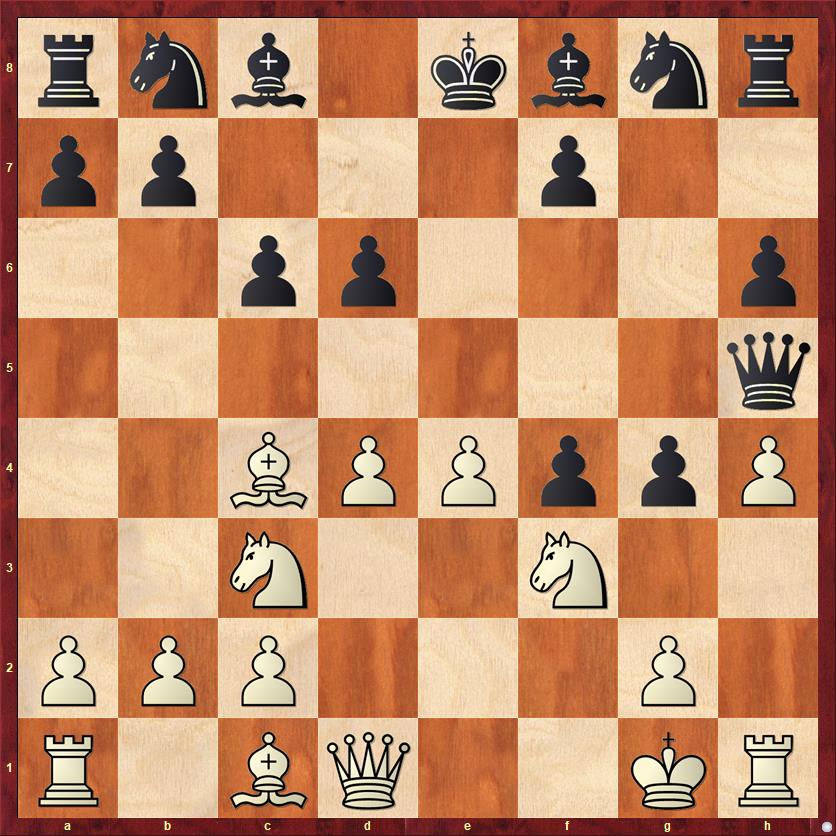

FEN: rnb1kbnr/pp3p2/2pp3p/7q/2BPPppP/2N2N2/PPP3P1/R1BQ2KR w kq – 0 10

For a must-win game, I couldn’t have asked for a better position. Juande is playing coffeehouse chess, not developing any pieces except his queen. Even better, this is a position we had gotten to previously in chess club, and I had prepared a new response. Actually I prepared it for the previous year’s Santa Cruz Cup, and then Juande crossed me up by playing the Sicilian Defense instead. So I got to play my theoretical novelty a year later than expected!

10. Nh2! …

Previously I had always played 10. Ne1. But the point of this move is that White’s knight will be much better placed on f1, where it can go to g3. Also, of course, there’s a tactical point: if 10. … Qxh4? 11. Be2! (a great computer find) Black has no good defense to the threat of Nxg4. For example, if 11. … g3 12. Ng4 Qg5 13. Rh5! Qxh5 14. Nf6+ wins Black’s queen. If Black doesn’t take the rook on move 13, then the f-pawn falls and probably the g-pawn will, too.

10. … f3 11. Nf1 …

All of White’s pieces now develop harmoniously. My knight can come to g3 and my bishop to e3 or f4. Meanwhile, Black’s pieces are all still sitting at home (except the queen), and the Black pawns on f3 and g4 are really not much of a threat to White’s king. They actually get in the way of Black’s pieces. All in all, White definitely has compensation for his gambit pawn. Black, in fact, decides to sac a pawn back to try to lure White’s king back out into the open, but this idea did not work very well.

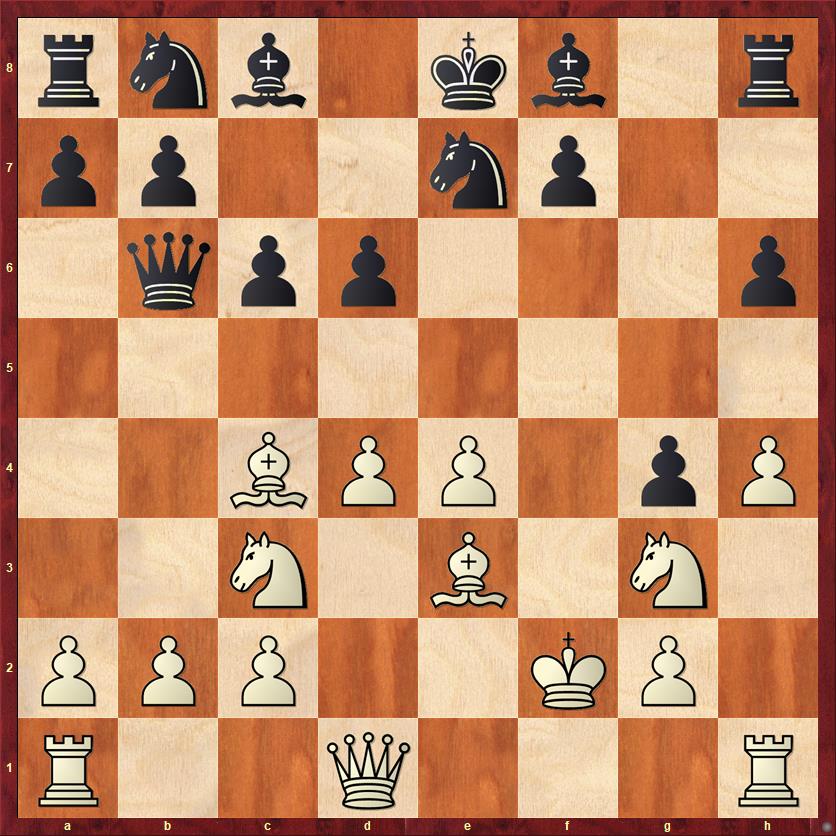

11. … Ne7 12. Ng3 f2+?! 13. Kxf2 Qa5 14. Bd2 Qb6 15. Be3 …

FEN: rnb1kb1r/pp2np2/1qpp3p/8/2BPP1pP/2N1B1N1/PPP2KP1/R2Q3R b kq – 0 15

Of course White would be thrilled if Black grabbed the pawn on b2, wasting even more tempi with his queen. This is a case where you don’t even bother analyzing variations. You just look at the incredible disparity in development and the weaknesses in Black’s position (the pawn on f7, the hole on f6). White must have much more than sufficient compensation for a pawn.

15. … h5 16. Qd2 Qa5

Now we can calculate the variation. If Black goes pawn-hunting he loses his queen: 16. … Qxb2? 17. Rhb1 Qa3 18. Nb5! cb 19. Bxb5+ followed by 20. Rb3.

17. a3? …

I don’t like this plan. White is starting to get sucked into coffeehouse chess too, moving pawns instead of pieces. A much more straightforward plan is to finish castling by hand with 17. Rhf1 and 18. Kg1, and then start loading up on the f-file with Qf2 or doubling rooks. I can just hear Jesse Kraai saying, “Simple chess.” My move wastes a couple of tempi and gives Black a chance to get back in the game.

17. … Bg7 18. b4 Qc7 19. Rae1 a6?

This is the one move by Black in this game that I really don’t understand. Lack of development is Black’s biggest problem, so now is the time to play … Nd7 or … Be6.

20. Bb3 Be6 21. d5 cd 22. Bd4! …

Not 22. Nxd5? Bxd5 23. ed Bc3. With 22. Bd4 White opens the e-file and improves the position of his least effective attacking piece. (Well, except for the rook on h1, but that’s coming…)

22. … Be5 23. ed Bd7

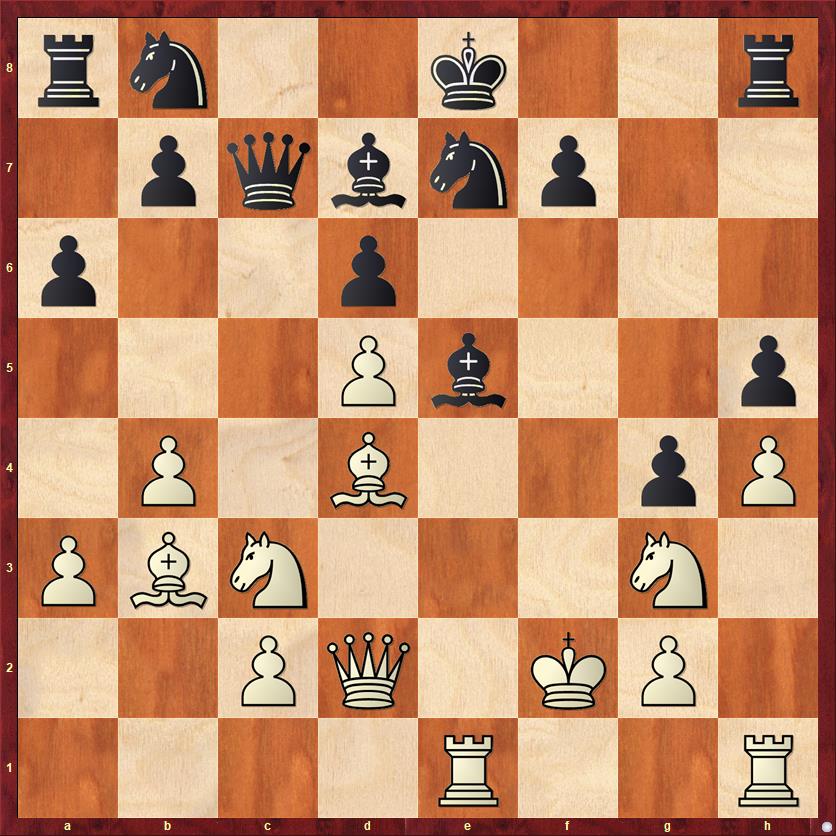

FEN: rn2k2r/1pqbnp2/p2p4/3Pb2p/1P1B2pP/PBN3N1/2PQ1KP1/4R2R w kq – 0 24

And now, let the fun begin!

24. Rxe5! …

I loved this move, compared to 25. Bxe5 de 26. d6 Qb6+, which gives Black some chance to defend. A King’s Gambiteer should always be willing to sacrifice the exchange for an attack.

24. … de 25. Re1!? …

During the game I thought this was a brilliancy, and for sure it is played in true King’s Gambit style. However, my bravado covers up a failure to analyze properly. The computer says that 25. Bc5! is more effective, a move with multiple points. It threatens d6, of course. It threatens Bxe7, so that Black can’t castle. More importantly, if Black moves the knight away he still can’t castle. I think that I didn’t play 25. Bc5 because I didn’t see a good answer to 25. … b6. But that’s crazy! The best answer to 25. … b6 is the simple one, 26. Bxe7! Kxe7 27. Qg5+. If 27. … f6 28. Qg7+ either checkmates Black or wins a rook. On Black’s best move, 27. … Kf8, White’s attack after 28. Nce4 is just tremendous, with all of his pieces pointed at Black’s king, who has almost no defenders. Fritz evaluates this position at +16 pawns for White!

25. … f6

Black should probably call White’s bluff with 25. … ed. White’s attack is still plenty strong, but at least Black has some chance to defend. For example, on 26. Qg5 the computer analyzes 26. … Qd6 27. Nce4 Qg6 28. Nf6+ Kd8 29. Qe5 Nc8 30. Nxd7 f6! 31. Qxf6+ Qxf6+ 32. Nf6 Rf8, which it evaluates as equal. (I would evaluate it as “a lot of chess left to be played.”) A better move order is 26. Nce4 right away. Black still can’t castle because 26. … O-O? 27. Nf6+ leads to checkmate. Best, according to the computer, is 26. … Qe5 27. d6. White is probably winning but again, there is a lot of chess left to be played.

26. Nce4! ed

Juande finally accepts the sacrifice, but under worse conditions than before.

27. d6! Qb6 28. Nxf6+ Kd8 29. de+ …

A very key point, which Juande perhaps overlooked, is the fact that this capture comes with check. So Black doesn’t get a chance to play … Qxf6.

29. … Kc8 30. Nxd7 Kxd7 31. Ne4! …

White has lots of ways to win, but I liked this one, which brings my last attacker into play and defends all of Black’s possible checks. White, of course, would love it if Black played 31. … Kxe7 32. Nc5+, when Black’s king would be completely alone against four voracious White pieces.

31. … Kc8 32. Qf4 d3+ 33. Nc5 …

White threatens checkmate in two different ways. Game over.

33. … Nd7 34. e8Q+ Black resigns

This is as beautiful a win as you could ask for in a must-win situation. But the tournament wasn’t over! Juande and I were tied, 1-1, which meant that we went to a playoff. The format was similar to the World Cup: we would play a pair of games at a time control of game in 25 minutes. If the match was still tied, we would go down to game in 10 minutes. If it was still tied after that, game in 5 minutes. And finally, if it was still tied, we would play an Armageddon game, White with 5 minutes, Black with 4 minutes, and draw odds in favor of Black.

I’ll tell you a secret that is not very secret: I hate speed chess. I’m not as good at speed chess as regular, “slow” chess. So I was not very optimistic. I had beaten Juande the previous year at the 25-minute stage, and I figured he would probably get his revenge this time. However, I think that he was the only person more nervous than me! He had been very nervous in the previous year’s playoffs, smoking a cigarette between rounds (which I had never seen him do before).

What actually happened was a scenario that would be hard to make up. In three straight mini-matches I won the first game as Black. And in three straight mini-matches, he won the second game as Black! So we were now down to the Armageddon game. I looked at him and he looked at me, and one of us asked the other, “Do you really want to play this game?” The other one said no. We agreed to be co-champions.

We had two spectators, Yves Tan and Cole Ryan, who had also come to play their playoff match (they were playing for 5th and 6th places). They had long since finished, but they stuck around to see who would win the match for first place. Of course, they were outraged. Cole said, “Wimps!” And I understand that spectators want a decisive outcome. But for me, this event crystallized my loathing for the Armageddon format. The thing I don’t like about it is that an Armageddon game is not a chess game. It’s an odds match. I do not want to decide a straight-up chess match by playing some altered version of the game.

In this particular case, there was another consideration that made us even less eager to play the Armageddon game. Remember that Black had just won six consecutive games in our match. And yet in Armageddon, Black gets the advantage of draw odds! Under the circumstances, it looked as if the winner of the tournament would be decided by a coin flip. Whoever won the coin flip and got the Black pieces would win the tournament. So what Juande and I were saying was that we really didn’t want the tournament to be decided by a coin flip. We had both played too well for that. I had won my must-win game with a beautiful exchange sacrifice and piece sacrifice. Juande had won three must-win games as Black under progressively tenser conditions. It did not seem fair for one of us to lose because of a coin flip.

And what’s wrong with co-champions? No one (aside from Yves and Cole) would care that Santa Cruz had co-champions instead of champions. In fact, even if we were talking about a state championship or a national championship, why is it so darn important to have only one champion?

So Juande and I were co-champions, and I have never regretted it. There are some things I regret in my chess career, but that is not one of them. Now, tell me what you think! Should we have played the Armageddon game?

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I’m all for co champs.