What can I possibly do for an encore after showing you my game with David Pruess from the 2006 Western States Open? That was a once-in-a-lifetime game, probably the only chess game I will be remembered for after I’m gone (if I’m remembered for anything). A game where everything went right, where I was in control from start to finish, where I defeated an International Master with a queen sacrifice, a theoretical novelty that had been played in correspondence chess but never before in an OTB tournament … It was just everything I could ever hope for.

I feel lucky that I lived in a fairy tale for one game in my life. But let’s face it: That’s not real chess. Real Chess is confusing. In Real Chess, things go wrong. You do stupid things, but you have to keep going and scrounge for counterplay. I feel as if I still owe you a game of Real Chess from 2006, and that’s what I’ll give you today.

But there’s a twist. I’m going to give you the game with no annotations. I think that’s the best way to recreate the “fog of war” conditions during the game, when neither my opponent nor I really understood what was going on. In this game especially, I think that computer analysis makes it too clear what was going on. To appreciate the battle, you need to be in the trenches with us.

The event was the 3rd Santa Cruz Cup. This was a series of invitational events that were organized by Eric Fingal from 2003 to 2008. I enjoyed these tournaments so much. As an amateur, you rarely get a chance to play in a tournament where you know everybody and everybody knows you. For me, Eric’s tournaments were an all-out struggle. I was the highest-rated player in the first two, and second-highest in the final three, after Juande Perea joined us. But really there were four or five experts who were all at the same level: Juande, me, Ilan Benjamin, Jeff Mallett, and (in the last year) Dan Burkhard. Then there was a rotating cast of Class-A and Class-B players who weren’t really a threat to win the tournament but could definitely hand the experts a stinging defeat on any given day.

The winners of the Santa Cruz Cup were as follows: 2003, Ilan Benjamin; 2004, Dana Mackenzie; 2005-6, Dana Mackenzie; 2006-2007, Juande Perea and Dana Mackenzie in a tie that we mutually agreed not to break; and 2007-8, Juande Perea. Except for the first year, the format was an interesting one that I liked a lot. We had eight players, whom we split into two groups of four. Just as in professional sports, we had a “regular season” (a double round robin within each group of four) followed by “playoffs” (two-game matches among the top four).

In 2005-6, the players who qualified for the playoffs were no surprise, the highest-rated four. In the first round of playoffs, Ilan Benjamin defeated Jeff Mallett, 1.5-0.5, while Juande and I split our two games, 1-1. We then went to a round of two 25-minute games, which I managed to win 1.5-0.5. (This turned out to be a warmup for our epic battle in 2007.)

So Ilan and I went to the championship match, which was a sort of “rubber match,” given that he had won the tournament in the first year and I had won it in the second. And I have to say, I got insanely lucky in this match. In both games, Ilan completely out-prepared me in the openings, and I should have lost both games. But of course, the game usually doesn’t end after the opening: then comes the middlegame, and the fog of war. The first game was a see-saw affair where we both had our chances and ended up taking a draw, in a position where we had mutual checkmate threats. The second was just a debacle, a tragedy for Ilan. He basically busted one of my favorite opening variations. I followed some mis-remembered analysis and played with even less caution than normal, and we got to a position where Ilan (according the computer) had a six-pawn advantage. But then he played a series of horrific blunders. First he played a rook sac that was sound and should have won, but was objectively unnecessary. Then he followed the sacrifice up incorrectly … and that’s the problem with sacrificing material. You mess up, and suddenly you are just a rook down. Or in this case, he ended up with a queen for two rooks and two pieces, and he had to resign.

I’m not going to show you the second game, even though it was the one that decided the tournament. It’s just too embarrassing for Ilan and for me. But the first game was a hell of a game, and gives you an idea of how fun and how challenging the Santa Cruz Cups were for me.

Remember: I’m not showing you any analysis of this game. Annotate it yourself! I will, however, insert diagrams of positions where some interesting things happened, or could have happened, or were about to happen.

Ilan Benjamin — Dana Mackenzie, 2/5/2006

3rd Santa Cruz Cup, Championship Round, Game 1

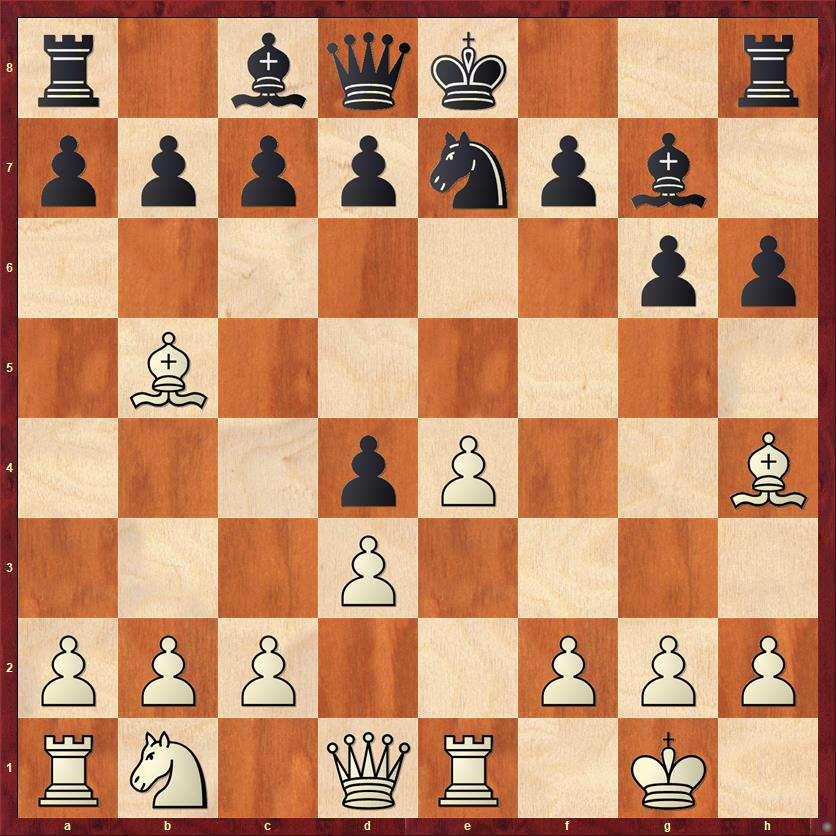

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nd4 4. Nxd4 ed 5. O-O g6 6. d3 Bg7 7. Re1 Ne7 8. Bg5 h6 9. Bh4 …

FEN: r1bqk2r/ppppnpb1/6pp/1B6/3pP2B/3P4/PPP2PPP/RN1QR1K1 b kq – 0 9

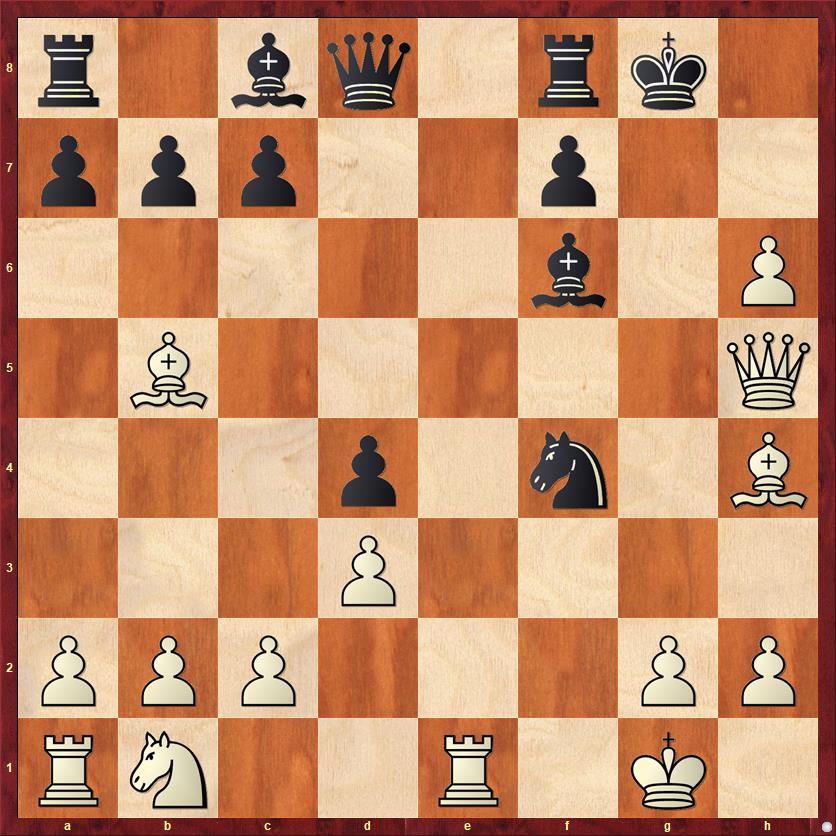

9. … O-O 10. f4 d5 11. ed g5 12. fg Nxd5 13. Qh5 Nf4 14. gh Bf6

FEN: r1bq1rk1/ppp2p2/5b1P/1B5Q/3p1n1B/3P4/PPP3PP/RN2R1K1 w – – 0 15

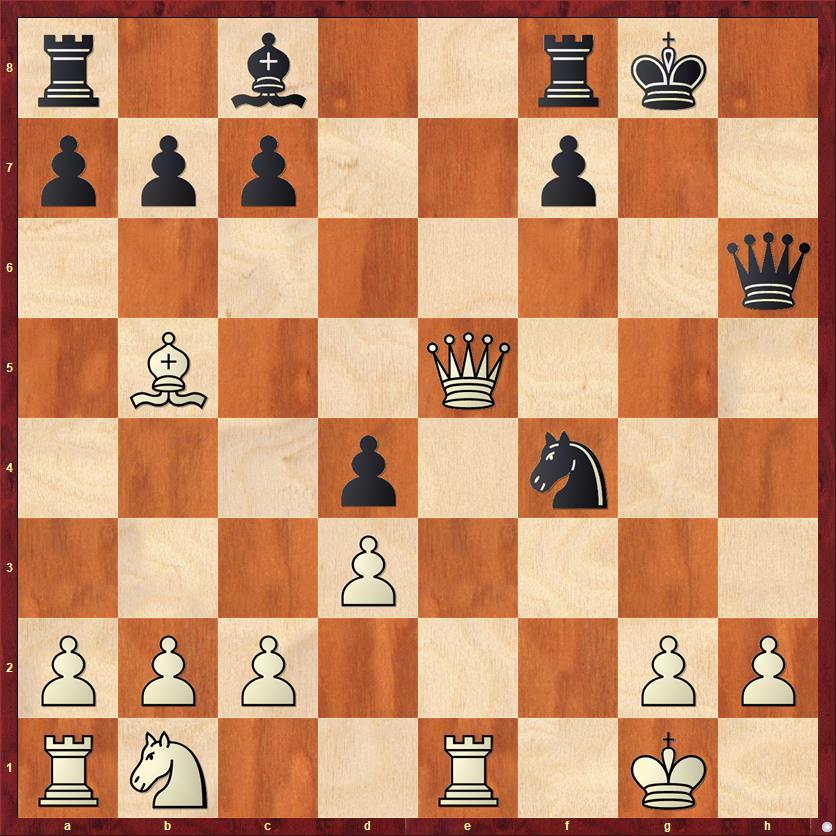

15. Bxf6 Qxf6 16. Qe5 Qxh6

FEN: r1b2rk1/ppp2p2/7q/1B2Q3/3p1n2/3P4/PPP3PP/RN2R1K1 w – – 0 17

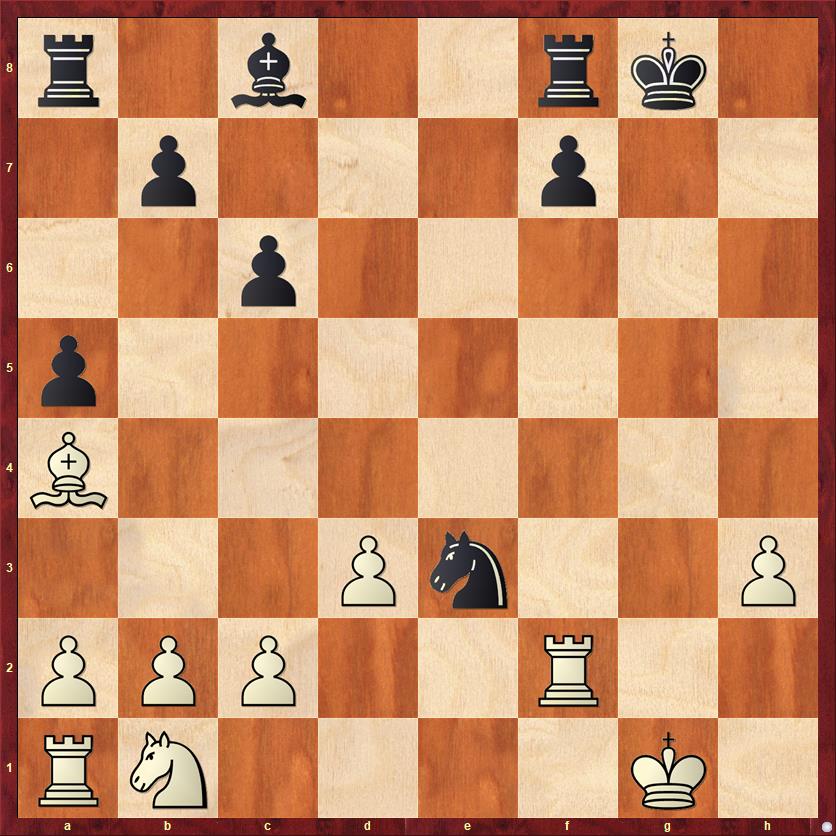

17. Rf1 Nxg2 18. Qxd4 Ne3 19. Rf3 …

FEN: r1b2rk1/ppp2p2/7q/1B6/3Q4/3PnR2/PPP4P/RN4K1 b – – 0 19

19. … Ng4 20. h3 Qc1+ 21. Rf1 Qe3+ 22. Qxe3 Nxe3 23. Rf2 c6 24. Ba4 a5

FEN: r1b2rk1/1p3p2/2p5/p7/B7/3Pn2P/PPP2R2/RN4K1 w – – 0 25

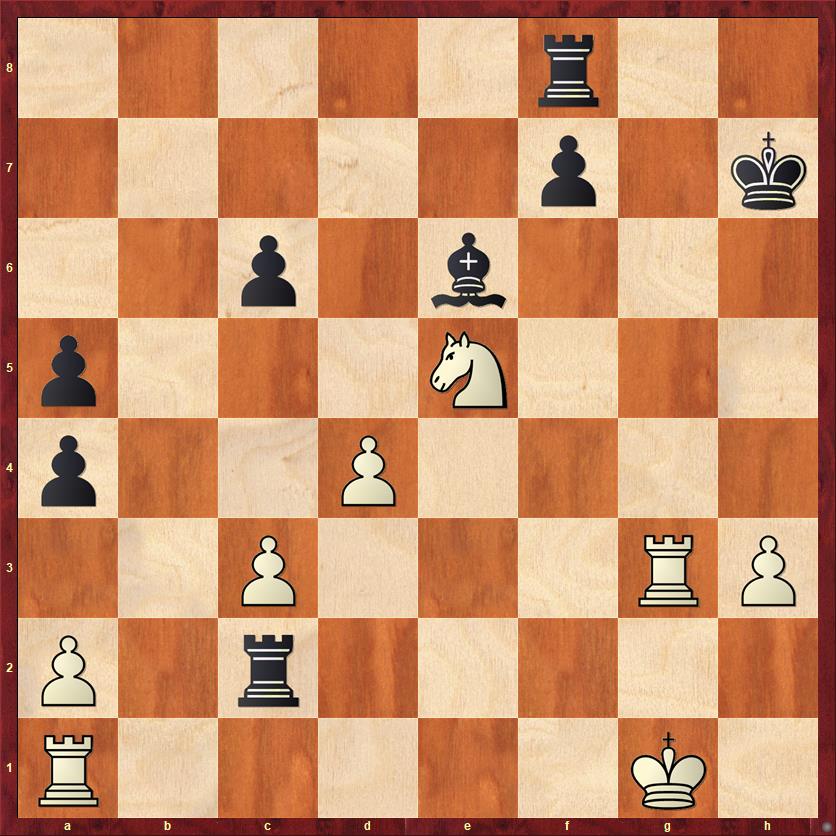

25. c3 b5 26. Rf3 ba 27. Rxe3 Rb8 28. Na3 Rxb2 29. Nc4 Rc2 30. d4 Kh7 31. Rg3 Be6 32. Ne5 …

FEN: 5r2/5p1k/2p1b3/p3N3/p2P4/2P3RP/P1r5/R5K1 b – – 0 32

32. … Bxa2 33. Nd7 Rd8 34. Nf6+ Kh6 35. Re1 Rb8 36. Ng4+ Kh7 37. Nf6+ Kh6 38. Ng4+ Kh7 39. Nf6+ 1/2-1/2

So, what did you think about the game… and the experiment? Was it more interesting to have to work out by yourself what was happening? Or do you think I’ve shortchanged you by not giving any annotations?

If you feel as if I’ve shortchanged you, then here’s a short comment on each of the diagrams.

Diagram 1 (after 9. Bh4): The biggest question is whether to play 9. … g5 or not. I didn’t play it because I thought it might loosen my position too much, but then after 10. f4 I felt uncomfortable because of White’s strong and mobile center. This motivated me to play the not really sound pawn sacrifice, 10. … d5?!

Diagram 2 (after 14. … Bf5): White had a couple of opportunities to trade queens while remaining a pawn up. First is the really cool move 15. Qe5, which kind of forces 15. … Bxe5 16. Bxd8. Less fancy but also effective is 16. h7+, which chases my king to a dark square so that after 16. … Kh8 17. Qe5, Black has to trade queens. With queens traded, my counterplay would have been much less dangerous.

Diagram 3 (after 16. … Qxh6): Probably the biggest turning point of the game. White has to worry about threats like 17. … Bh3 or (if 17. Qxd4) 17. … Qg5. Ilan’s move 17. Rf1 was intended to oust my knight before these threats became a problem, but he overlooked a tactical shot. Fritz 9 (in 2006) recommended 17. Re4; Fritz 17 (in 2021) recommends 17. Nd2.

Diagram 4 (after 19. Rf3): The tide turns again. I chose not to go for the rook with 19. … Nxc2, which looked like too reckless an adventure with White’s queen, rook, and possibly knight set to devour my kingside. But the computer thinks that I can weather the storm (with some very deep analysis to prove it) and evaluates the position as +4 pawns in my favor. I have to say that this may be a weak point in my game. I really hate grabbing material and then having to suffer through a difficult defense. But sometimes that is the right way to play.

Diagram 5 (after 24. … a5): Yet another turning point. Ilan’s move 25. c3? looks like a knee-jerk response, to give the bishop some air, but it is completely unnecessary. More forceful is 25. Rf3, to kick the knight out right away. Ilan came up with this idea on his next move, but by then it was too late.

Diagram 6 (after 32. Ne5): The last turning point in a game full of them. After either 32. … Rxa2 or 32. … a3 Black is probably winning. 32. … Bxa2? was a time-pressure blunder. I completely missed White’s answer, 33. Nd7!, which is extremely strong because the knight gets to f6 and sets up checkmate threats. The position after 35. Re1 is pretty amusing because the only way for Black to avoid being checkmated is to threaten a checkmate of his own! That is, after 35. … Rb8 White can’t play 36. Re4 (threatening mate in one) because Black strikes first with 36. … Rb1+ and mate next move! It’s like a scene from a thriller movie where everyone is pointing a gun at everyone else. But in chess, we can just agree to a draw — probably a disappointment to the spectators but a huge relief to the players.

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

“I chose not to go for the rook with 19. … Nxc2, which looked like too reckless an adventure with White’s queen, rook, and possibly knight set to devour my kingside. But the computer thinks that I can weather the storm (with some very deep analysis to prove it) and evaluates the position as +4 pawns in my favor”

Hi Dana,

I make this point in my upcoming chess book. Humans don’t play like computers. They make many errors. Unless you feel confident that you won’t make any errors, why give your opponent real practical chances to win the game? I think you did the right thing.

Diagram 3 (after 16. … Qxh6): Re4; Fritz 17 (in 2021) recommends 17. Nd2.

Without looking at any variations, this would have been my choice too. White has three spectator pieces – pieces that aren’t affecting play in the critical zone, the king side. The Black rooks are also spectator pieces.

The B5 bishop is playing a small role, preventing Re8 1so 7. Nd2 rushes reinforcements to the king side and turns the White spectator pieces into active participants. The loss of the g pawn does not kill White. and it costs Black three tempos.- two to threaten and capture the pawn, another to retreat the capturing piece. White will use those tempos for Rf1 and Rf2 and Ne4 with an big force advantage in the critical zone.

Computer analysis may prove my positional evaluation to be wrong, but you have to trust your judgments during the game. The position cries out for more development, so develop.

“Diagram 5 (after 24. … a5): Yet another turning point. Ilan’s move 25. c3? looks like a knee-jerk response, to give the bishop some air, but it is completely unnecessary.”

This is quite an interesting position. I disagree with the question mark .

First, the threat of b5 and a4 muss be met eventually. so the c pawn or the a pawn will have to move at some point. The c3 move follows the principle of making necessary moves first.

Second, if you have a light square bishop you want your pawns on dark squares in this ending.

Third, it opens the way for White to complete his development. If I had the White pieces I would have followed c3 with Nd2 intending Kh2, Rg1+ and Nf1.

So c3 achieves three purposes and looks like a reasonable move.

On the other hand, the knight on e3 is very strong and White should try to dislodge it if he can. The rook move to f3 protects the h pawn and attacks the knight, so at first sight it also achieves two purposes. But the h3 pawn can’t be safely captured so Rf3 only achenes one purpose.

The “principle of maximum effectiveness” says that all things being equal, the move that accomplishes more objectives is the best move. Mark Weeks wrote an interesting blog piece on this concept.

Again, computer analysis may prove my positional evaluation to be wrong, but you have to trust your judgments during the game.

BTW, I liked the challenge of finding my own ideas, without being influenced by annotations, and keeping the analysis in a separate part of the blog. I’m also happy with the old format.

Great comment! One other reason I wanted to write the post this way is that I never did a thorough analysis of this game *without* the computer. Up to now, all my posts have been based on old-fashioned non-computer analysis first, revised (sometimes heavily revised) by computer analysis later. But in this game, I skipped the first step, and that may be true with some upcoming posts as well.

You can be sure that my decision to play 19. … Ng4 instead of 19. … Nxc2 was not taken lightly. But when the computer says “+4” after 19. … Nxc2, it’s hard to avoid castigating myself for excessive timidity.

I completely agree with your comments on 17. Nd2. Both sides got too caught up in the middlegame action before finishing their development. I didn’t even develop my queen bishop until move 31!

I agree with the computer (and disagree with you) on 25. c3. The point of playing 25. Rf3 first is to chase the knight away so that White can then play 26. c3 and save his bishop. If Black chooses not to cooperate and plays (after 25. Rf3) b5, then White plays 26. Rxe3 ba. This is like the game continuation but with two key differences: White is a tempo ahead, and he has the square c3 available for his knight so that he can play 27. Nc3 and immediately tickle Black’s weak pawn. Now 27. … Rb8 (as in the game) has no force because 28. Nxa4 wins a pawn and defends the b2 pawn.

The only general principle here is: “Distrust all general principles.” In the abstract, your principle of maximum effectiveness is great, but in this concrete situation White’s move 25. c3 eventually allowed the invasion of Black’s rook on the b-file, which drastically changed the dynamic of the game.

But if I had to formulate a counter-principle, it would be this. When you have two moves, A and B, that can be played in either order, make sure to consider both possible orders. Even if A followed by B seems more “natural” on general principles, make sure to also consider B followed by A. I have missed so many wins because I didn’t remember to do this or even think of doing it.

Hi Dana,

I wanted to introduce Mark Weeks’ principle if Maximum Utility idea to your readers. I agree with you. The tactics in this case overrule the principle.

If 25 Rf3 Nd1 26. Nd2 Nb2 27. Re1 Na4 28. Rg3+ Kh8 29. re5 or 28. Kh7 Re4 and mates.

I think White is ok after 25. c3 b5 27. Bc2 Bf5 28. Na3 Nc2 29. Nc2 Rg2+ Kh8 Bd3 Nd4, but there is a lot of chess to be played from here.