One of the best things about living in California is the fact that you’re so close to Hawaii! Close in a relative sense, of course. It’s 2400 miles from San Francisco to Honolulu, which is about the same as the distance from San Francisco to Washington, DC. But still, there’s a big psychological difference between one 2400-mile flight and two.

In 1998, the U.S. Open chess championship was held in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, on the Big Island, and I decided to play in it. This was a trip full of firsts: My first U.S. Open. My first trip to Hawaii. The first time I saw a hula dance. My first win over a (future) chess grandmaster. It was also just a really great trip, the first vacation that Kay and I had taken together since we moved to California.

Hawaii is the perfect place for a tournament like the U.S. Open. Traditionally that tournament has been played at a relaxed, European-style pace of one game a day (although there’s also a “short schedule” option these days; I don’t remember whether there was one in 1998). You don’t want to play more than one game a day when you’re in Hawaii, because there are so many other things to do. Go snorkeling. Climb a volcano. Go to a luau. And there’s something in the tropical air in Hawaii that just says, “Relax. Take it easy.”

This trip was even enjoyable for Kay, who enthusiastically came along to this tournament. It was the only tournament I’ve ever been to where there was a contingent of chess wives. Kay would go out to the balcony with the other wives, sip mai tais and watch manta rays. They called themselves the Manta Ray Watching Society (although I think that Manta Ray Society would have been better, because it abbreviates as MRS).

The 1998 U.S. Open was historic because it was the only U.S. tournament ever that both Judit Polgar and Sophia Polgar played in. I think that Susan Polgar was also there, but she apparently didn’t play. (My memory may be faulty.) Anyway, Judit tied for first place with Boris Gulko with a score of 8 out of 9, a solid result for both of them. Another famous chess family was also represented, although they were not quite as famous yet as they would become: Hikaru Nakamura and his older brother, Asuka. Why is it that the younger brother/sister always turns out to be the best?

In the U.S. Open I played nine people from nine different states: Hawaii, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, Colorado, Illinois, California, Pennsylvania, and Washington, thus making it a true “United States” Open for me. I emerged with a score of 5.5 out of 9, which was not good enough to win a prize. Probably the best and most interesting game of the tournament was one that I lost. (I annotated it here as part of my “Six Memorable Games” series.) It was that kind of year.

But since I’ve already shown you that game, I’ll show you my only really memorable win of 1998. As I wrote in my diary, “In the seventh round I defeated Vinay Bhat, one of the brightest up-and-coming child stars. (He finished second in this year’s high school tournament of champions. Since he is just entering ninth grade and the winner has just finished twelfth grade, the way is wide open for him to win it four years in a row.)”

Well, I’m not a very good prognosticator. Vinay never did win the Denker High School Tournament of Champions, and no one has ever won it four years in a row, or even three. But Vinay did eventually become a grandmaster, and thus he is the only grandmaster whom I’ve ever beaten. Of course, I did it the “cheap” way, by winning before he earned the GM title. But at the time of this game he was already a pretty strong player, with a rating of 2398.

This game isn’t a masterpiece. Basically he made one really bad mistake and that was the difference. Still, it was a good fighting game, and the middlegame was quite interesting.

Vinay Bhat — Dana Mackenzie, 8/7/98

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nd4

By now I had settled on the Bird Variation as my #1 defense against the Ruy Lopez, and against 1. e4 in general.

4. Nxd4 ed 5. O-O g6

And I had also settled on the Blackburne Subvariation (fianchettoing the KB) as my go-to setup.

6. d3 Bg7 7. Bc4 d6

But I had not settled on this move yet. In 1997, against an expert named Clarence Lehman, I had played 7. … Ne7 8. Bg5 h6 9. Qf3! O-O 10. Bf6, with what I considered to be an unpleasantly cramped position for Black. I’m not sure if it’s really that bad; in fact, I ended up winning the game against Lehman. Nevertheless, 7. … d6 was my attempt to improve.

8. f4 Be6 9. Bb3 …

After the game I thought that 9. Bxe6 was the “crucial test.” But after 9. … fe 10. f5 Qf6! Black seems to be okay. 11. Qg4? looks plausible, but after 11. … Nh6! 12. Bxh6 Bxh6 White’s f-pawn is pinned, and Black’s bishop will find a beautiful square on e3. So actually Vinay’s judgment was exactly correct. 9. Bxe6 fe 10. f5 is the sort of line you play only if you can see your way to a clear advantage. Otherwise, 9. Bb3 is a calm, flexible, master move.

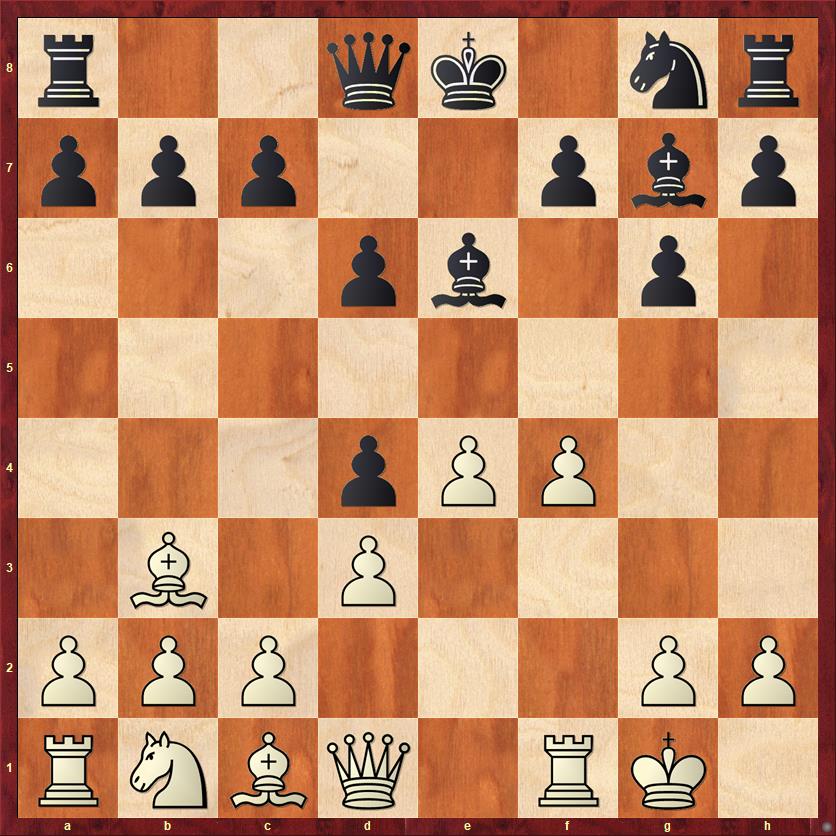

FEN: r2qk1nr/ppp2pbp/3pb1p1/8/3pPP2/1B1P4/PPP3PP/RNBQ1RK1 b kq – 0 9

However, “calm” and “flexible” has never been my approach to chess. Here the calm, flexible approach would be 9. … Nf6, but I wanted to play more ambitiously.

9. … Qh4?!

I liked this move because it prevents White from playing moves like Qg4 or Bg5. But it’s not clear whether the queen is well placed here or whether it’s going to become a target.

10. Nd2 O-O-O?!

Going even farther out on a limb. Maybe 10. … Ne7 was better, but Black is already getting in trouble because of his overambitious eighth and ninth moves. For example, 10. … Ne7 11. Nf3 Qh5 12. c3! is a promising pawn sac for White, planning Qb3 and taking aim at the weak pawns on e6 and b7.

11. f5 Bxb3 12. ab a6 13. Nf3 Qh5 14. Bd2 Nf6

Hoping for 15. Nxd4?, which is met effectively by 15. … Nxe4 and even more effectively by 15. … Ng4 16. Nf3 Bd4+! 17. Kh1 Nf2+.

15. Ra5! …

An excellent move, which I did not see coming. All of a sudden Black’s queen is starting to feel uncomfortable.

15. … d5!

Definitely in the spirit of Mackenzie chess. First of all, I should say that … d5 is almost always part of Black’s plan in the Bird Variation, so it’s not too surprising that I played it here. It is usually better than … c5, which leads to a static and brittle pawn formation in the center. Especially in this position, 15. … c5? would come under merciless attack by 16. b4 Nd7 17. bc dc 18. b4!

When you feel your position starting to slide downhill, it’s often a good idea to complicate the position and force your opponent to make difficult decisions. Here, White faces a big decision about how to proceed. Should he push ahead with 16. e5, possibly overextending his pawns? Should he threaten a fork with 16. Ng5? Should he play the computer’s daring move, 16. Qa1, threatening a berserk rook sacrifice on a6? It’s one thing to say that White should be better in this position. But it’s another thing to prove it.

16. Ng5 …

A practical move that tries to keep a solid advantage and minimize Black’s counterplay. The computer prefers both 16. Qa1 gf 17. Rxa6! and 16. e5 Ng4 17. f6 Bh6. But you should only play these moves if you’re able to analyze as well as a computer.

16. … Qxd1 17. Rxd1 Rd7

The computer prefers 17. … Rde8, to prevent 18. e5. But 17. … Rd7 seemed logical to me, defending all of my weak points.

18. fg?! …

White is seduced by the opportunity to win a pawn. The computer still likes 18. e5 better. It gives the line 18. … Ng4 19. f6 Bh6 20. Nf3 Bxd2 21. Rxd2 Re8 22. Kf1 Ne3+ 23. Kf2. It’s a tricky position to evaluate, where each side has a difficult-to-defend pawn, the Black pawn at d4 and the White pawn at e5. At first glance I feel as if Black is holding his own, but the computer disagrees and evaluates White as +1 pawn. I’ll let the reader decide.

By comparison, in the game variation White wins a pawn but loses a couple tempi to do so, and Black’s minor pieces get terrific activity.

18. … hg 19. ed Nxd5 20. Nxf7 …

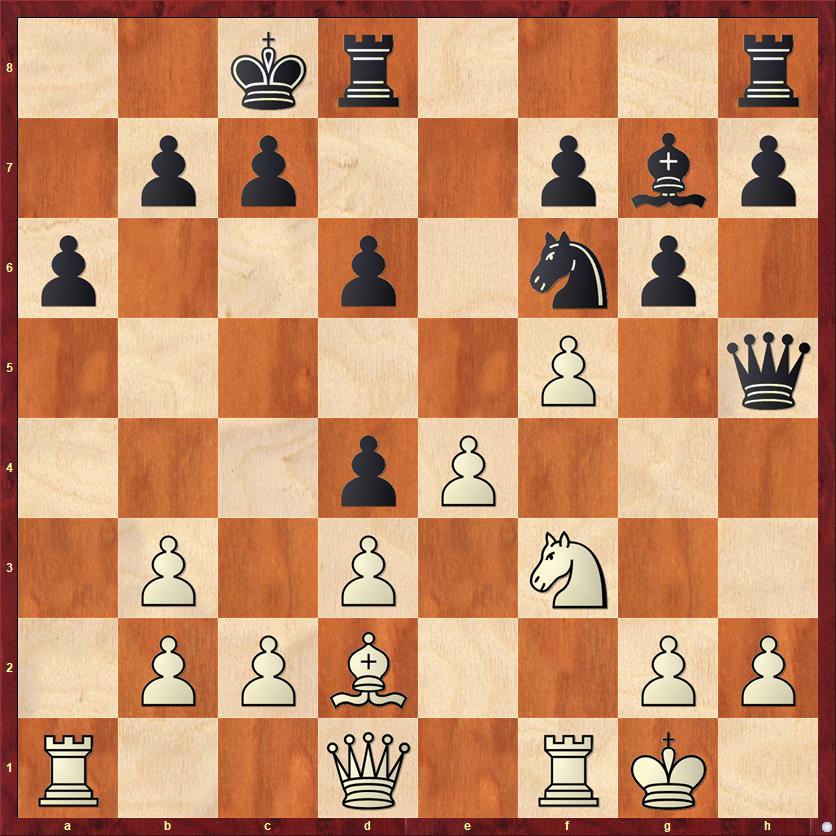

FEN: 2k4r/1ppr1Nb1/p5p1/R2n4/3p4/1P1P4/1PPB2PP/3R2K1 b – – 0 20

Which way should the rook go?

20. … Rf8?

Wrong! This is my worst move of the game. Although I played some other questionable moves, like 9. … Qh4 and 10. … O-O-O, they were at least logical moves, played with clear goals in mind. But this move accomplishes nothing. It makes a one-move threat with no convincing followup.

The best move was 20. … Rh5. Let’s start with the obvious: I’m now threatening to take on f7. The most natural reply is 21. Ng5, but now 21. … Ne3! is stronger than in the game. 22. Rc1? would lose material after 22. … b6, so White is forced to play 22. Bxe3 de. I wrote in my notebook, “Black has many threats, such as … Bd4, … Bxb2, … Bh6, and … b6.” Actually, 23. g4 puts the kibosh on some of those threats, but at least after 23. … Rh4 24. h3 I can win back my sacrificed pawn with … Bxb2. A trickier line is 21. Rf1, but again 21. … Ne3! seems completely satisfactory. If 22. Rxh5 Nxf1! Black comes out ahead.

Generally speaking, Ne3 is a dream move for Black in the Bird Variation, and if I can play it effectively, it bodes very well for my chances.

21. Ng5 Ne3 22. Rc1 …

Compare this with the variation above where I had the rook on h5. In that line, 22. … b6 was a killer. Here it doesn’t do so much. But I had trouble finding any other way to improve my position. I’d like to play something like … Rd6 or … Re7, but both of them run into 23. Bb4. Finally I decided to go ahead and play 22. … b6 anyway, even though it loses a pawn.

22. … b6

Often if you are a pawn down and have nebulous counterplay, it helps to sacrifice a second pawn in order to get more concrete counterplay. For example, would you rather be one pawn down with half a pawn of compensation, or two pawns down with 1 1/2 pawns of compensation? I would always go for the second, because 1 1/2 pawns of compensation is a lot. Against human opponents, that kind of advantage has a tendency to grow.

That isn’t really the case in this position; here I am two pawns down with maybe one pawn of counterplay, at best. Nevertheless, it worked! Partly it was sheer luck, but “luck is the residue of design.” I wouldn’t have gotten lucky unless I had sacrificed material to get to a position where I could get lucky.

23. Rxa6 Kb7 24. Ra4 Re7 25. Nf3 R7f7

Pinning the knight because of a mate threat on f1. Keep that in mind!

26. Bxe3 de 27. Re4 Bh6 28. Ne5?? …

Throughout this game Bhat has played with admirable patience, but at this crucial moment he plays more like an impatient ninth-grader (which he was) than a future grandmaster (which he also was). After a simple, cautious move like 28. Re1 there is no way for Black to break through. 28. Ra1 may be even better, to keep Black from occupying that file.

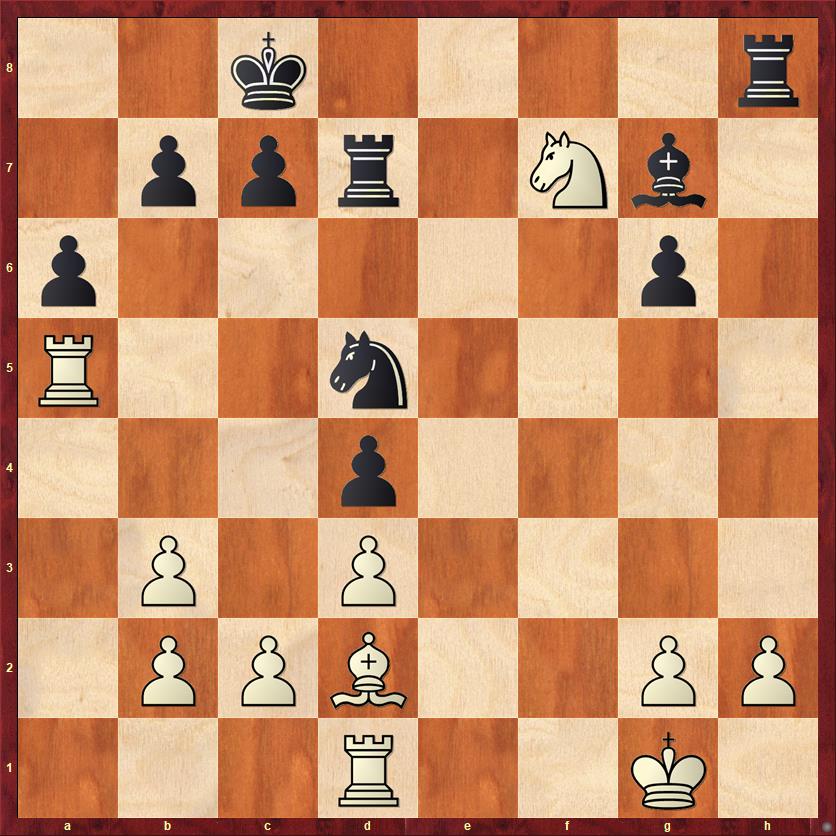

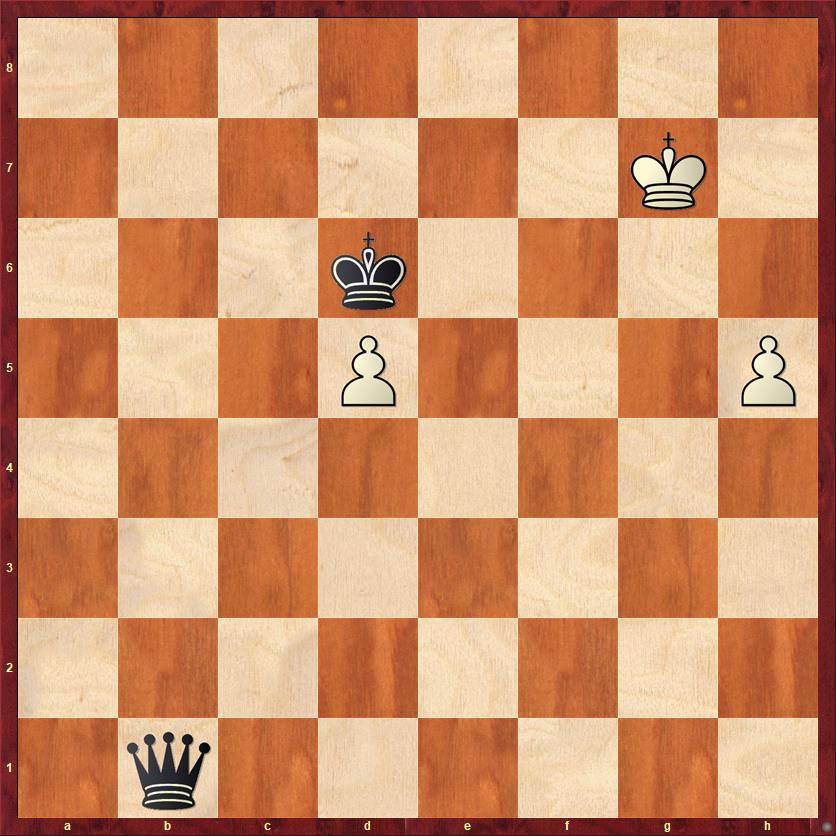

FEN: 5r2/1kp2r2/1p4pb/4N3/4R3/1P1Pp3/1PP3PP/2R3K1 b – – 0 28

This really shouldn’t be a difficult position to solve, especially after the hint I gave you after move 25.

28. … e2!

Bhat must have overlooked or forgotten that this move threatens mate on f1 as well as discovering an attack on his c1 rook. He can’t defend them both.

29. Nxf7 Bxc1 30. Re7 …

Another possibility is that Bhat saw this far and thought he was okay because 30. … e1Q+ 31. Rxe1 Rxf7 32. Rxc1 keeps a three-pawn advantage. But my next move must have woken him up real fast.

30. … Rxf7!

A decoy sacrifice. Also winning is 30. … Bxb2, but this move gets more style points.

31. Rxe2 Bxb2

With a piece for two pawns, Black is completely winning. The rest of the game is kind of lengthy and tedious, because White has a pawn majority on each wing, so there is no quick win to be had by pushing the pawns. Black’s winning plan is to try to arrange a trade of rooks. Then in the B vs. 2P endgames, one of two things will happen. If White tries to break through on the kingside, Black will stop his passed pawn(s) with his bishop and promote a pawn on the queenside. If White tries to bring his king to the queenside and play defense, Black will use zugzwang to force the White king away from the pawns.

32. g4 Rf4 33. h3 Bd4+ 34. Kg2 Kc6

Dangling a carrot in front of White, hoping he will play 35. Re6+ Kd5 36. Rxg6. That would allow Black to get a passed pawn on the queenside very quickly after 36. … Re2+, … Rxc2, and … Rc3.

35. c3 Bf6 36. d4 Kd7 37. Re3 Bh4 38. Re2 Rf8 39. d5 Re8

Just for instruction purposes, here’s an example of the zugzwang strategy: 40. Rxe8 Kxe8 41. Kf3 Ke7 42. Ke4 Kd6 43. c4 Kc5 44. Kd3 Kb4 45. Kc2. It seems as if Black will never be able to win White’s pawns, because they are all on white squares, but 45. … Bf6 creates a zugzwang and the pawns will all fall, one by one.

40. Rc2 Re3 41. b4 Bf6 42. c4 Rb6 43. c5 Rb2!

First step accomplished: the rooks are coming off.

44. Rxb2 Rxb2 45. Kf3 Bc3 46. Kf4 Bxb4

For timid souls, 46. … Bf6 would also be fine. The move I chose allows White to get connected passed pawns, but I was confident in my ability to count moves and I knew that the pawn race wouldn’t even be close.

47. cb cb 48. Kg5 Bc3 49. Kxg6 Kd6

I thought this was a useful interpolation. But it turns out that an out-and-out pawn race also works: 49. … b5 50. Kf5 b4 51. Ke4 b3 52. Kd3 b2 53. Kc2 Kd6 54. h4 Kxd5 etc.

50. g5 b5 51. Kf7 b4 52. g6 b3 53. g7 Bxg7 54. Kxg7 b2 55. h4 b1Q 56. h5 …

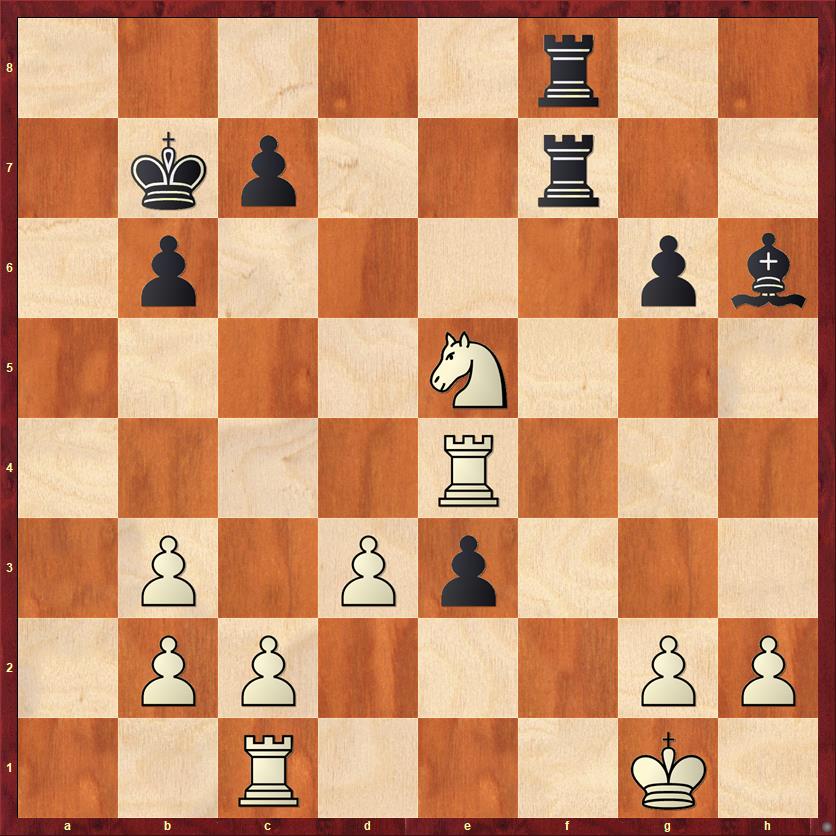

FEN: 8/6K1/3k4/3P3P/8/8/8/1q6 b – – 0 56

White is obviously two tempi short of where he would like to be, with a pawn on h7. But let’s at least get a tiny instructional benefit from playing out this tedious endgame. Let’s be generous to White and move his pawn from h5 to h7 (maybe White could do this surreptitiously while Black is going to the bathroom). What would be the evaluation?

You might say that with the pawn on h7, this is a known draw. But that’s wrong, because White still has a pawn on d5, a “traitor pawn!” Black wins by checking with the queen until the queen gets to g6. At that point, White has to move his king to h8, in front of the passed pawn. Ordinarily this would create a stalemate. But in this position, Black would then just step out of the way of the d-pawn, with … Ke5 for example, and then after d5-d6 he would checkmate in two moves with … Kf6 and … Qg7 mate. (Or, alternatively, … Qf7 and … Qf8 mate.)

Strangely, I did not know this theme until three or four months ago, when I encountered it in a game against the computer. The theme is that K+Q versus K+RP on the seventh rank is normally a draw, but if you put another pawn on the board somewhere, it’s not a draw any more! This little tidbit of knowledge might someday earn you a win in a position that your opponent thinks is a draw. You can thank me if it happens!

Okay, back to the last few moves of our game, which does not require such advanced knowledge.

56. … Qb7+ 57. Kh8 Qc8+ 58. Kh7 Qd7+ 59. Kg6 Qe8+ 60. Kh6 Qh8+ White resigns

I think that this game touches on some important, broad problems of strategy for which there are no “one size fits all” answers. So you’ll see a lot of qualifiers like “often” and “usually” in my take-home lessons for today. Lessons:

- Given a choice between a flexible move that offers a sure, comfortable advantage, or a committing move that leads to unclear complications, masters will usually choose the flexible move. [White move 9.]

- On the other hand, when you are defending a position that you feel is strategically going downhill, it is often a good idea to go into unclear tactical lines to make things more difficult for your opponent. [Black move 15.]

- If you have a choice between variation (a) that wins a pawn but solves all of your opponent’s problems, or variation (b) that doesn’t win material but gives your opponent lasting problems, you should strongly consider option (b). It’s all about patience versus immediate gratification. [White moves 18-20.]

- Sacrificing two pawns for significant, concrete compensation is often better than sacrificing one pawn for nebulous compensation. [Black move 22.]

- King and queen versus king and rook-pawn on the seventh is a draw. But king and queen versus king, rook-pawn on the seventh, and some other pawn somewhere else is a win. Beware the “traitor pawn”! [Black move 56, fantasy variation where he goes to the bathroom and White pushes the h-pawn to h7.]