And now let us begin the downward half of my chess chronicle! I jest, of course. The last 25 years, since I moved to California, have been the best of my life, both in chess and otherwise.

On July 29, 1977, I wrote in my diary, “Daddy asked me what I thought I’d be doing twenty years from now. … It turned out that we all agreed it was an impossible question to answer. The future is a myriad of possibilities — some we perceive now, some we perceive later, some we never perceive.”

But now I can answer my father’s question. On July 29, 1997, I was in Durham, North Carolina, and staring at the greatest precipice of my adult life. For nine months I had studied in the Science Communication Program at UCSC with nine other students, learning how to be science writers. The last step of the year-long program was to do a summer internship, which would be a bridge between our academic studies and our new careers. I obtained an internship at the magazine American Scientist, based in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.

It was the perfect gig for me, because it gave me a chance to spend one last summer in North Carolina, where I had lived from 1983 to 1989 and still had many friends. The pace of life in North Carolina and the pace of work at American Scientist were mellow and relaxed. But July 29 was my second-to-last day. Two days later I would start a new phase of my life — not a student, not employed, but a freelancer. No one could tell me what to do any more; no one could fire me; but I could very well starve.

“My gosh, I’m really on my own now, sink or swim,” I wrote in my diary. “No more job with a regular paycheck. No more school. The future is now, or it will be what I make of it. I think I’m 80 percent excited and 20 percent terrified. The thing is that I’ve been given the tools to succeed. But I’ve never done it before. I’m flying solo!”

If so, that autumn was like flying a biplane with a balky engine. The money trickled in at first. Mostly I was writing for a website called Science NOW, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), churning out one or two stories a week. They were very short (4 paragraphs), very formulaic (Kay called them “McJournalism”), and they didn’t pay much ($150 per story) … but they paid. And they kept me busy. When you’re starting out as a freelancer, that’s all you can ask for, to be paid and to be busy. The best practice for writing is to write. Even before the year was out, the AAAS was starting to give me longer and better-paid assignments for the print magazine (Science), and American Scientist was also giving me editing assignments. At the end of 1997, I was able to write:

“This year has been great; I’ve been more successful than I expected more easily than I expected. But there are some ways I can improve. I want to work more on long-term projects with higher-quality research. I’d like to decrease my dependence on writing Science NOW articles. … I’d like to develop more of a unique voice and a sense of passion. Am I passionate about mathematics? Or is there some other subject I care about more? Finally, and perhaps in tandem with the last point, I want to keep an eye out for possible book subjects. I don’t necessarily want to write a book proposal by the end of next year, because I may need to develop more expertise in a field before I do that, but I’d like to at least have a destination in mind.”

With such epic changes going on in my life, I didn’t play much chess in 1997 — only two tournaments. But in one of them I did pretty well, and I played my first games against two people who would become longtime friends, Michael Aigner and Andy Lee. The tournament was the northern California state championship (note: we have two state championships in California, north and south!). I tied for first in the expert (under-2200) section with Andy Lee and Okechukwu Iwu.

It’s funny to talk about Andy Lee and Michael Aigner as experts, because they’ve both been masters for so long, and that’s the only way I can think of them. Andy’s peak rating was 2405, and Michael’s was 2347 — both of them a lot better than me! But at the time of this tournament they were rated below me — 2032 for Andy, 2047 for Michael. Even so, I still consider both of these games (a draw against Andy, a win against Michael) to be good accomplishments. Even if they weren’t masters yet, they were budding masters. (And in the years to come I would play many more budding masters — one of the pleasant and sometimes annoying challenges of living in a state with lots of strong young players.)

Of the two games, I think that the game against Michael is more unusual and more memorable, so that is the one I’ll show you. I felt as if I was skating on the edge of a precipice for the whole game, but mostly the precipice was my own creation.

Michael Aigner — Dana Mackenzie, 9/2/97

1. f4 …

On Facebook and elsewhere, Michael calls himself “fpawn” because this was the opening he liked to play when he was coming up. I think when he got to master level he played the f-pawn less and less, especially as White. This is the only game (out of 11 tournament games we’ve played) when he tried it against me. I think that he keeps the name “fpawn” just for old times’ sake.

1. … d5 2. Nf3 c5

There’s another irony here. These days I would happily play this position as White, and I would play 3. e4!?, going into the Bryntse Gambit. But no one had heard of it back then, and Michael plays a more normal move.

3. e3 Nc6 4. Bb5 e6 5. O-O Ne7 6. b3 a6 7. Bxc6+ …

This move surprised me. White gives away the two bishops without getting any real compensation in the form of pawn weaknesses. Unless you consider the pawn on g7 to be a pawn weakness.

7. … Nxc6 8. Bb2 Qc7 9. d3 b5?!

This is when I start going a little nuts. There were lots of saner alternatives: 9. … f6 if I want to keep open the possibility of castling kingside, 9. … b6 if I want to castle queenside but don’t want to create easy targets for White.

10. Nbd2 Bb7 11. Qe2 O-O-O 12. a4 f6?

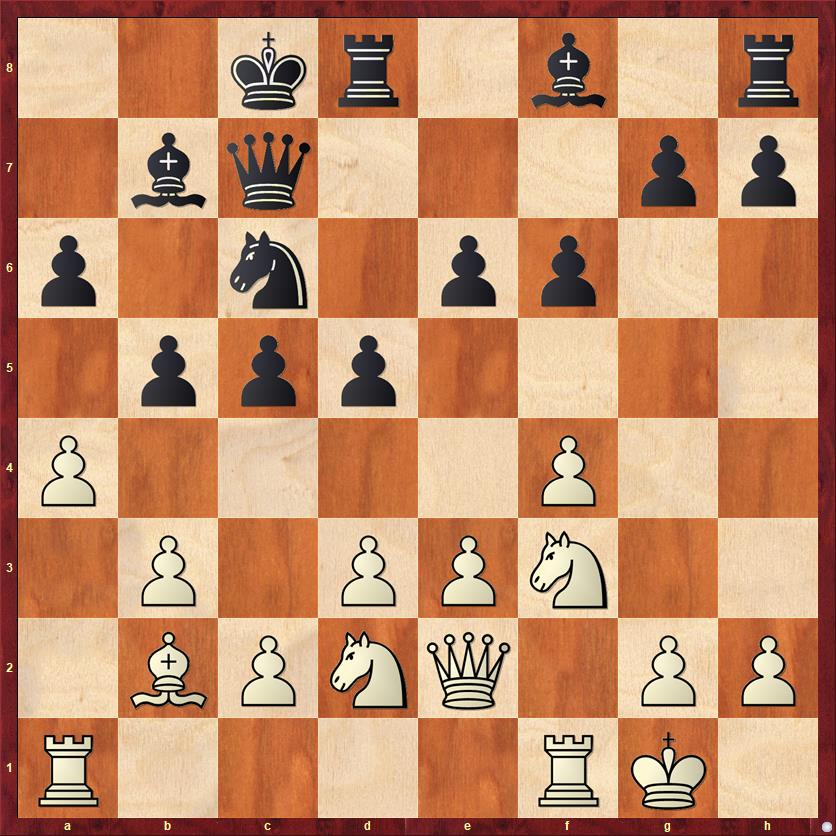

FEN: 2kr1b1r/1bq3pp/p1n1pp2/1ppp4/P4P2/1P1PPN2/1BPNQ1PP/R4RK1 w – – 0 13

Of course I should have played 12. … b4. Why should I let White open one, perhaps two files pointing toward my castled king? It makes no sense. This move shows a bad habit I’ve had since forever: I sometimes can’t resist playing unconventional moves just because they are unconventional. Basically I was saying, “Okay, I’ll let you have the a-file. I’ll bet you can’t do anything with it.” Perhaps, to go a little bit deeper, I thought that his pieces were not sufficiently well-positioned to attack me on the queenside. The knights are kind of clumsy and in each others’ way.

Still, it was an absolutely pointless risk. In this game, I got away with this nonsense. But usually, against Michael, I didn’t. My lifetime record against him, including this game, is 2 wins, 1 draw, and 8 losses!

13. ab ab 14. d4 c4 15. Rfb1 …

Move order, move order. If I were White, I would have been inclined to trade pawns first. When he didn’t do that, I started thinking about ways I might be able to take advantage of the move order he chose. If I could just push my pawn to c3, not allowing the pawn trade, then it would make his rook move look kind of stupid. Of course I can’t do that yet, but I decided to set it up with

15. … Nb4?!

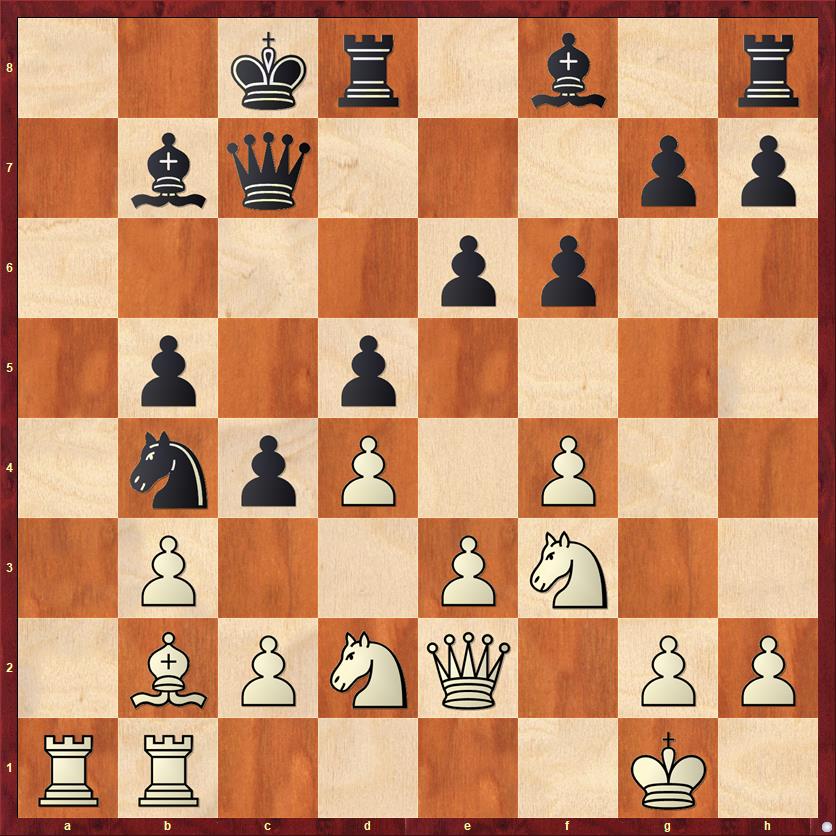

FEN: 2kr1b1r/1bq3pp/4pp2/1p1p4/1npP1P2/1P2PN2/1BPNQ1PP/RR4K1 w – – 0 16

Objectively, after going over it on a computer, I think my move was probably a mistake. But chess between humans is never objective. A very key point is that I have seized the initiative. He cannot ignore my threats of … Nxc2 or … c4-c3. What would you do?

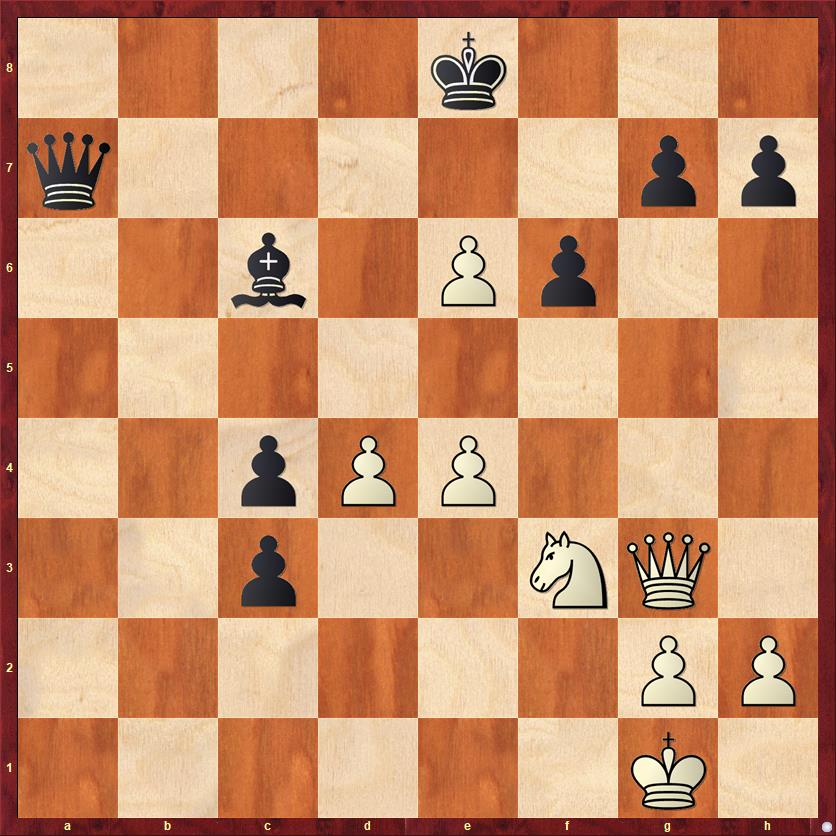

The critical move, I correctly realized, is 16. Bc3, although it can be preceded by 16. cb if White feels that the pawn trade is advantageous. The computer thinks that White should not trade yet but should play 16. Bc3 right away. Then the “main line” goes 16. … Nxc2 17. Ba5! (a good way to make me pay for letting him open the a-file) 17. … Qc6 18. Ra2 Na3 19. Rc1! Rd7 and now the surprising 20. b4!? (diagram)

FEN: 2k2b1r/1b1r2pp/2q1pp2/Bp1p4/1PpP1P2/n3PN2/R2NQ1PP/2R3K1 b – – 0 20

This is why the computer thought that White should not trade away the b-pawn. It saw that four moves later the b-pawn could be used to trap my knight.

What do you think about this position? I’m going to lose that knight on a3, no doubt whatsoever. The computer thinks White has a 2.5-pawn advantage, which normally means an easy win. But White’s extra piece is that bishop on a5, which has absolutely no moves. No moves now, and no chance of moving for a long time in the future. In my opinion, it’s far from clear that White is winning. In fact, the position “feels” a lot like one where Black is a pawn up! And a very solid pawn at that.

One argument in favor of White is that he has a clear path to victory: trade all the pieces. If we can get to a king-and-pawn endgame (in effect), his bishop will finally re-emerge because my king can’t cover all three squares b6, c7, and d8.

But on the other hand, what if Black just blockades the position? White will have no open lines. Can White actually win?

Furthermore, what if Black plays for a win? It looks to me as if this is a real possibility. My bishops are better than his knights, and I might be able to work up a pretty good kingside attack in addition to my ace in the hole, the passed pawn on c4. I would love to give it a try!

This is exactly the sort of position where a computer is no use at all. Basically its evaluation is just based on counting the material. But it has no way to answer the questions I’ve just asked.

In the end, Michael chose not to enter into any of these complications, and instead he played

16. c3 …

I was relieved to see this, and I wrote in my notebook afterwards, “After 16. c3 I felt my position was completely safe.” The computer says I was wrong, and still assesses the position as +0.9 pawns for White. In view of the uncertainties about the 16. Bc3 variation, I think that you can make a strong case that Michael played exactly the right move. I think of him as a strong, pragmatic player, and 16. c3 is definitely a pragmatic move. It appears to give me a beautiful knight outpost on d3, but that is deceiving: it is very easy for him to trade off that knight. Meanwhile, he still has plenty of opportunities to make trouble for me on the a-file, the file I stupidly allowed him to open for his rooks.

16. … Nd3 17. bc dc 18. Ba3 Bc6 19. Bxf8? …

The first of two consecutive inaccuracies that cause White’s advantage to melt away. I can understand that Michael wanted to trade off his bad bishop while he had the chance. But this exchange actually helps Black more than White. It lets me connect my rooks and defuse White’s pressure on the a-file. White should have left the bishop tension on the board. It’s likely that I will have to play … Be7 or … Bd6 at some point, and then he can trade bishops. Because of his impatience, in effect, he loses a tempo rather than gaining one.

19. … Rhxf8 20. Ra6?! …

Another inaccuracy because it allows me to simplify and get my king out of trouble. The computer likes a completely different plan: 20. Nb3, with the idea of 21. Na5 forcing Black to make a decision about his bishop. As we’ll see, the lack of activity of this knight was one of the deciding factors in this game.

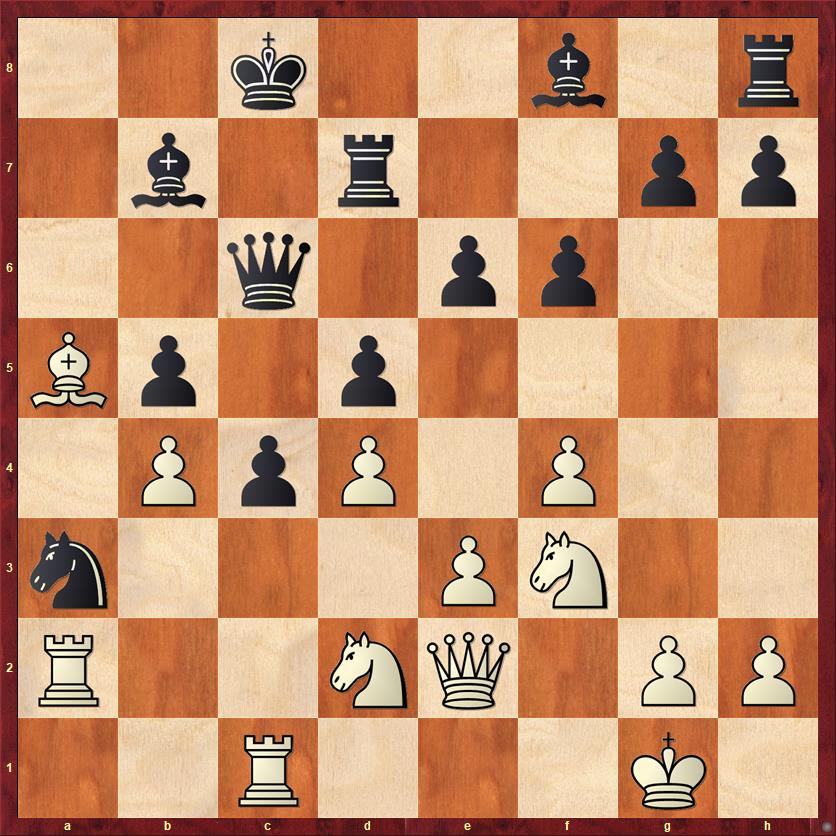

FEN: 2kr1r2/2q3pp/R1b1pp2/1p6/2pP1P2/2PnPN2/3NQ1PP/1R4K1 b – – 0 20

20. … Kd7

Time to move out of that apartment at #8 C Street. It was never a very comfortable place anyway.

21. Ne1 Nxe1 22. Qxe1 …

Here the computer comes up with a holy-crap variation that humans would never see: 22. Rxe1! with the idea of 22. … Ra8 23. Qg4!! Of course, 23. … Rxa6 would be met by 24. Qxg7+ winning either the rook or the queen, so Black will probably play 23. … g6, after which White plays another holy-crap move, 24. Ne4!!, putting both the knight and rook en prise. The best reply (according to the computer) is 24. … f5 25. Nc5+ Kd6 26. Qh4, with roughly equality.

Why get excited about a line where you have to play two “!!” moves just to get an equal position? Because in the game, Michael drifts into a less-than-equal position where I am the one calling the shots.

22. … Ra8 23. R1a1 Qb7 24. Rxa8 Rxa8

It’s very sad for White to have to let Black take over the a-file, but his hand is forced because of the weakness of the long diagonal, too.

25. Rxa8 Qxa8

Who would have thought that I would be the one who ended up controlling the a-file?

26. e4 Qa3

White’s position is starting to feel a little bit like the legend of the Dutch boy: plug a leak here, and another leak starts there.

27. Nf3? …

This knight has been a pretty sorry piece the whole game (that’s one reason why White should have given it something to do with 20. Nb3). Now it moves for the first time since move 10, and that move is the losing move of the game. I wrote in my notes, “27. Qg3 strikes at Black’s weaknesses more quickly.”

I’m going to skip the long and subtle computer analysis that basically agrees with what I thought — after 27. Qg3 Black still has all the winning chances, but White’s queen is able to create enough havoc that White might be able to save a draw.

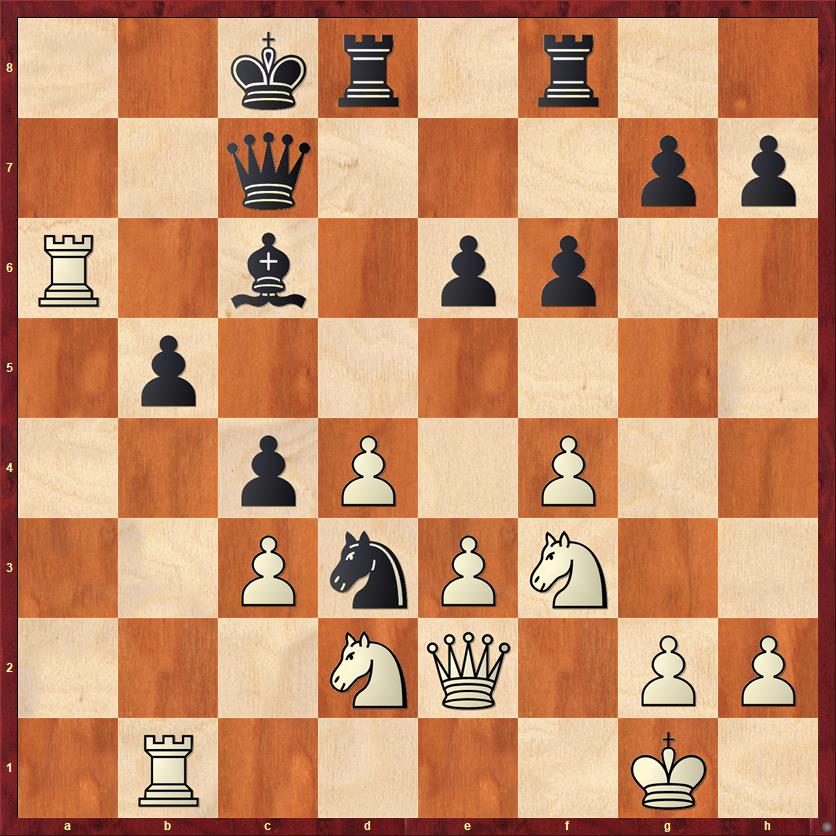

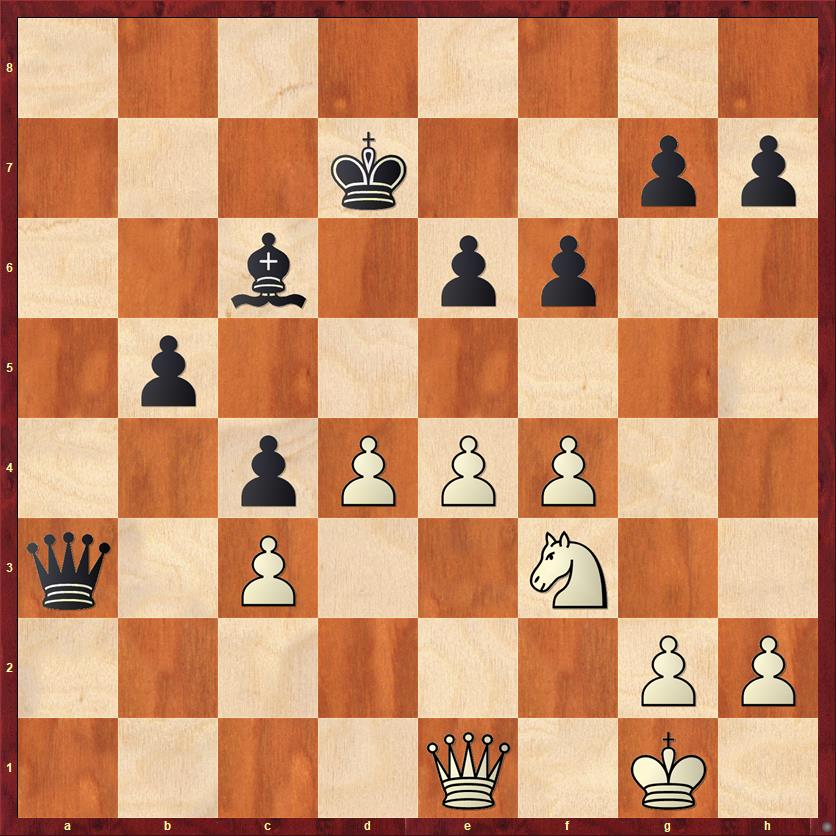

FEN: 8/3k2pp/2b1pp2/1p6/2pPPP2/q1P2N2/6PP/4Q1K1 b – – 0 27

There are many positions where Q+N are better than Q+B. This is not one of them! The only thing that matters in this position is Black’s ability to create an outside passed pawn, and White’s inability to stop it.

27. … b4!

White’s knight and queen are just really badly placed for stopping a pawn on the c-file. Michael desperately tries to “create havoc,” but I’m able to deal with it in the cruelest way: by simply ignoring his threats.

28. f5 bc!

In my notes I wrote, “Objectively simplest was 28. … ef 29. ef Bd5, but I was too enamored of the full-speed ahead approach with 28. … cb.” The computer, of course, loves the full-speed ahead approach.

29. fe+ Ke8!

I had the whole finishing combination worked out, and this was a key part of it.

30. Qg3 Qa7!!

FEN: 4k3/6pp/2b1Pp2/8/2pPP3/q1p2NQ1/6PP/6K1 b – – 0 30

I just love this move, 30. … Qa7. It’s aesthetically pleasing in so many different ways. First, I love it when the decisive move is a “quiet move.” I also love the geometry of the position, the way that from its distant outpost on a7 the queen controls every key square on the board. It protects g7. It protects b8. It pins the pawn on d4 (and also threatens to simply win that pawn with check if White should try to stop the c-pawn with 31. Ne1). And the queen is ready, on a moment’s notice, to swoop back down the board to a1, as we see in the game.

There’s only one significant square that my queen doesn’t control:

31. Qd6 …

But I was ready for that, too:

31. … c2!

As I said, full speed ahead! Maybe this last sacrifice was superfluous, because 31. … Bxe4 is also completely winning, but as I said above, I always like to defend by not defending at all. Go ahead and take my bishop, see if I care.

32. Qxc6+ Ke7 33. Qxc4 Qa1+ 34. Kf2 c1=Q

With two queens against a queen and knight, Black obviously should be winning. The outcome was never really in doubt after this, but I don’t blame Michael for playing on. With my king wandering around on a wide-open board, it will take me a while to escape from White’s checks.

I’ll give the remaining moves without comment:

35. Qb4+ Kxe6 26. Qb3+ Kd7 37. Qd5+ Kc7 38. e5 fe 39. Qxe5+ Kb6 40. Qe6+ Qc6 41. Qb3+ Ka5 42. h3 Q1a4 43. Qg8 Qac2+ 44. Kg1 Qd1+ 45. Kh2 Qc7+ 46. Ne5 Qxd4 47. Qa2+ Kb4 48. Qb1+ Ka3 49. Qf1 Qxce5+ 50. Kh1 Qa1 White resigns

Don’t worry, Michael got his revenge on me many, many times. In our eleven tournament games, as I mentioned above, he has won eight. In fact, according to the USCF web page, he is the only player since 1991 who has beaten me more than three times in tournaments! So he is definitely my #1 nemesis of all time. There were some people who beat me more than three times before 1991, but the USCF’s computer records don’t go back any farther, and I doubt that any of them beat me 8 times.