It was the best of time in 1994, and it was the worst of times. I’ll start with the “best,” and then get to the “worst.”

At the end of 1993, as I wrote in my last post, I had four good tournaments in a row, and my good fortune continued into the new year. Central Ohio had two big tournaments in consecutive weeks, the Ohio Winter Open in Springfield and the Cardinal Open in Columbus. I looked at it as a great chance to play a lot of games against strong players and maybe pick up some rating points.

From that point of view, the Ohio Winter Open was a failure. I lost in an upset in an early round to Gina Finegold, the wife of Ben Finegold, who was an expert. She played in the U.S. Women’s Championship later that year but didn’t do very well, and she has not played any tournaments since 1994. I have to wonder why. Did she and Ben part ways? Or did she just decide it wasn’t a good thing for two people in a relationship to both be serious chess players? When Kay and I started dating, she told me early on that she would never play chess with me, and I think that was probably a smart idea. (We did play Scrabble, though, and it created some frayed tempers from time to time!)

After the loss to Finegold, I came back with three straight wins and only lost 5 rating points when all was said and done. That gave me some momentum for the next week, and in the Cardinal Open I finally put it all together and had one of my best tournaments ever. I played four games against masters and won three of them, probably the first time I had ever done that in a five-round tournament. The highlight was my second consecutive win over IM Ed Formanek. However, I’ve already shown you my first win against him and I don’t want to add insult to injury by showing you the second.

Instead I’ll show you my game against Clark Harmon, a Life Master from Oregon who had for some reason traveled all the way to Ohio to play in the tournament. As in my other two wins against masters in this tournament, I managed to eke out a win an endgame that probably should have been a draw. The game is not a work of art by any means, but it’s a hard-fought battle, the kind of game that you feel really good about winning (and vice versa, that’s crushing when you lose). As I wrote in my diary, “None of my wins in this tournament were cheap.”

Because this was a long game decided in the endgame, I will fast-forward through a lot of the early parts of the game.

Clark Harmon — Dana Mackenzie, 1/22/94

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. e3 c5 5. Bd3 Nc6 6. Nge2 d6?!

In his Nimzo-Indian book, Svetozar Gligoric calls this move “pointless” and recommends 6. … d5. My plan is to exchange on c3 and play for control of the dark squares with … d6 and … e5, as in the Huebner Variation. We’ve already seen an extremely successful example of this strategy in an earlier post (Year 18 of my retrospective). However, there is a crucial difference: White has developed his knight on e2, not f3. This means that White can push his f-pawn right away and challenge Black’s attempt to form a solid barricade in the center. So Gligoric is probably right.

7. O-O Bxc3 8. bc e5 9. e4 O-O 10. h3 Re8 11. d5 Ne7 12. f4 ef 13. Bxf4 …

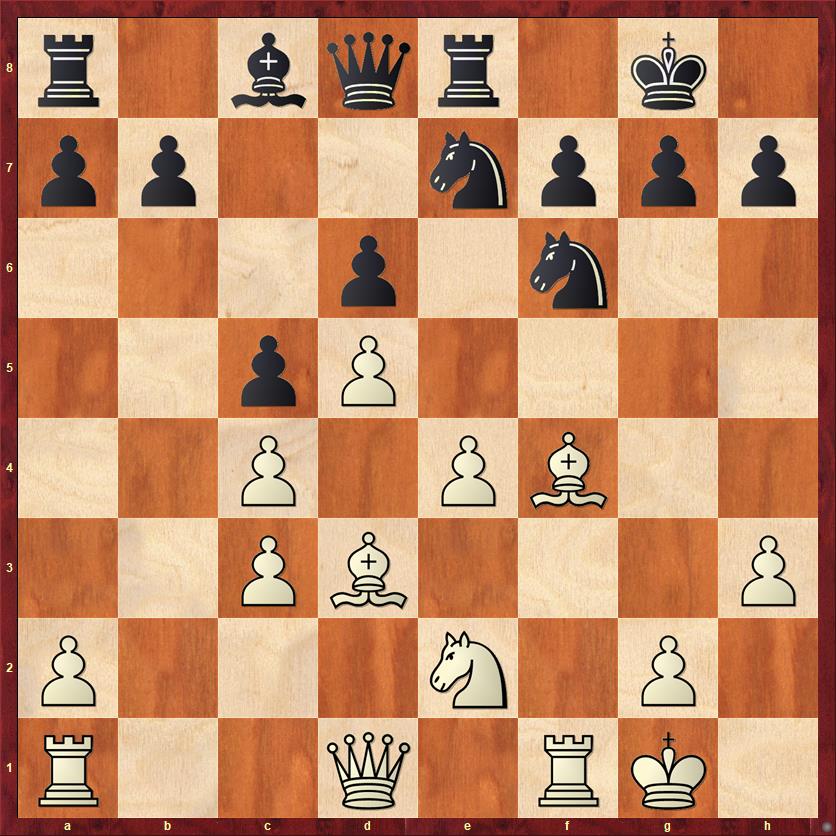

FEN: r1bqr1k1/pp2nppp/3p1n2/2pP4/2P1PB2/2PB3P/P3N1P1/R2Q1RK1 b – – 0 13

Here is a major turning point in the game. I played a move that the computer says is unsound, but which I am nevertheless proud of. I sensed a lot of unpleasantness ahead in this position. I was worried about White’s pawn break e4-e5, which I can’t prevent with 13. … Nd7 because the d-pawn hangs. 13. … Ng6 14. Bg5 allows White to cripple my pawn structure. Best, according to the computer, is 13. … Qc7, but I didn’t like this move because of 14. e5!? de 15. d6! In all of these lines Black faces an arduous defense. I have little patience for defense, so instead I sought a move that would give me the initiative. The move I settled on was

13. … b5!?

Here’s what I wrote in my chess notebook: “On 14. cb c4! 15. Bxc4?! Qb6+ White’s queenside pawns are a mess. 15. Bc2 would be better, but Black probably still has enough compensation. Another point of 13. … b5 is that it prevents 14. e5 (14. … de 15. Bxe5 bc 16. Bxc4 N7xd5 -/+).” The first two parts of this comment are probably over-optimistic. Even though White’s queenside pawns are messy, it’s more important that White has a lot of good piece activity and dangerous pressure on the f-file. In fact, the computer points out that 14. cb c4 15. Bxc4 Qb6+? is a mistake: after 16. Nd4 Nxe4 17. Qf3! Ng6 18. Be3! Qc7 19. Bd3 Black is getting into the same sort of passive position that I was trying to avoid, plus I’m already a pawn down.

What can I say? Of course the computer is right. But it’s fairly unlikely for a human master to play this way, because the lines demand a lot of precise calculation, and there is no reason for White to take this kind of risk. I feel certain that Harmon’s analysis was more intuitive, and went along the following lines: “Black is trying to distract me from a kingside attack by playing an unclear pawn sacrifice on the queenside. Although it might not be sound, there is no benefit for me in opening lines for my opponent’s pieces. I’ll just go ahead and let Black take on c4 if he wants; that pawn will be a dead duck anyway.”

Once you understand how masters think, you can use their thought process against them! Although my pawn sac was a semi-bluff, the last part of my comment shows that it did have a valid purpose. My move discourages e4-e5 if not outright preventing it. So the question is: How is White going to increase the pressure, if he can’t play e5?

14. Bg5? …

Not this way! The problem for White is that the f6 knight is not pinned, and I can simply relocate it to d7 and then e5, where it becomes a tower of strength. White should have waited to play this move after I move my e7 knight. A good way for him to improve his position in the meantime would have been 14. Ng3. If 14. … Ng6, now 15. Bg5 is a good move because the knight on f6 is pinned. If Black plays something else, say 14. … a5, 15. Bg5! is strong because White is prepared to answer 15. … Nd7 with 16. Nf5!

It’s interesting to see how after this one move pair, the gamble by Black on move 13 and the sloppy analysis by White on move 14, the game completely changes complexion. During the rest of the middlegame Black either stands even or slightly better.

14. … bc 15. Bc2 Nd7 16. Ng3 f6 17. Bf4 …

Here I was a little bit worried about the possibility that White might sacrifice the kitchen sink with 17. e5!? Nxe5 18. Bxh7+!? Kxh7 19. Qh5+ Kg8 20. Bxf6!? But Black just swallows all the material and comes out ahead after 20. … gf 21. Rxf6 Nf5! Black is +1.5 pawns according to the computer, but the position is very volatile and all three results are possible. In my notebook I wrote, “There are lots of lines, but the knight on e5 is a pillar of defense… as long as it remains, White has a hard time breaking through.”

17. … Ne5 18. Bxe5 fe 19. Qh5?! …

White is still thinking in terms of kingside attack, but that ship has sailed. The queen is misplaced here and ends up returning home in short order.

19. … Ng6 20. Ba4 Rf8 21. Rxf8+ Qxf8 22. Rb1 Nf4 23. Qd1 Ba6 24. Bb5 Bxb5 25. Rxb5 …

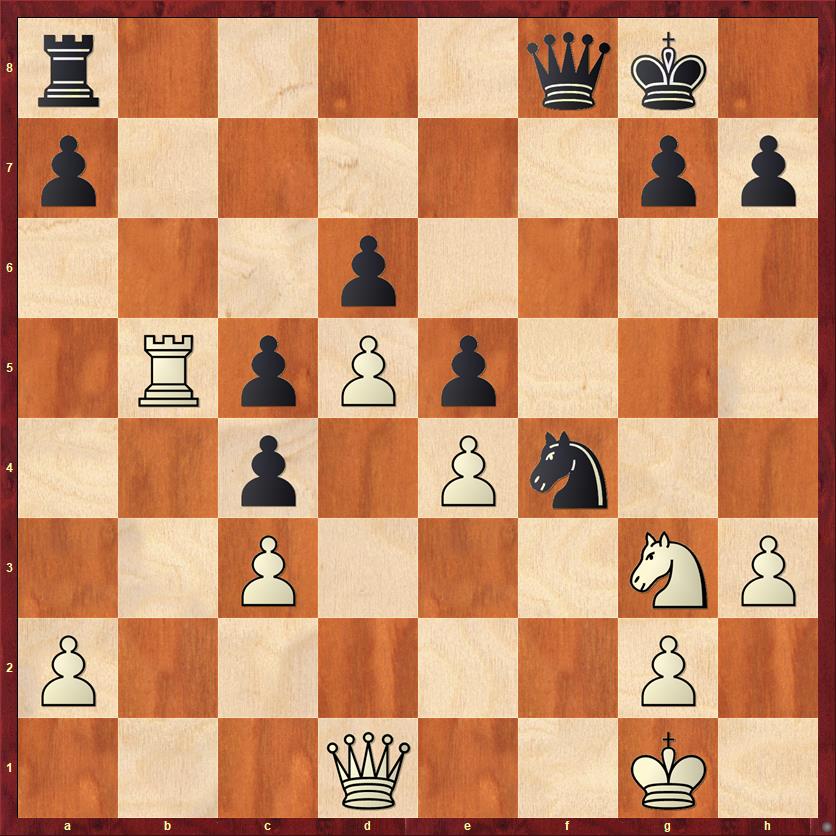

Time for a diagram, as we’re getting closer to the endgame.

FEN: r4qk1/p5pp/3p4/1RpPp3/2p1Pn2/2P3NP/P5P1/3Q2K1 b – – 0 25

Here I played an “automatic” move that the computer considers (initially) to be an inaccuracy.

25. … Rb8

To me, this move seemed (and still seems) completely obvious. Black doesn’t want White’s rook getting to the seventh rank. But the computer, initially, gave a +1 pawn evaluation to the strange move 25. … g6, literally inviting White to play 26. Rb7. Why? The point is that Black will now offer the rook trade with 26. … Rb8. If White snatches the a-pawn with 27. Rxa7?, Black gets a mammoth attack after either 27. … Rb2 or 27. … h5.

But now let’s get real. After 25. … g6 26. Rb7 Rb8, White is not going to go pawn-snatching. He is almost certain to play the same way he did in the game, 27. Qb1 — refusing to give up the b-file. The computer’s extremely lengthy analysis then goes 27. … Rxb7 28. Qxb7 h5 29. h4 Qd8 30. Qxa7 Qxh4 31. Qb8+ Kf7 (running to h6 doesn’t work because White will get to play Nf5+ with a perpetual) 32. Qc7+ Qe7 33. Qxe7+ Kxe7.

In what universe is this a sensible line? Black has allowed White to gain an outside passed pawn on the a-file, in return for the possibility of eventually getting a passed h-pawn. At this point the computer comes to its senses and admits that the position is equal. In other words, 25. … g6 was no better than the “automatic” human move that I played. Score one point for human intuition. But this is also why analysis with computers is so frustrating! We just wasted half an hour confirming the conclusion I came to in 5 seconds at the board.

26. Qb1 Rxb5 27. Qxb5 g6 28. Kh2 …

This move basically gives Black a free tempo. White should stop beating around the bush and should win back his pawn with 28. Qxc4. If 28. … Qb8 29. Qb3 the queen trade is more favorable to White than it is in the game.

28. … h5 29. Qxc4 h4 30. Nf1 Qb8

And now we get another key transitional moment.

FEN: 1q4k1/p7/3p2p1/2pPp3/2Q1Pn1p/2P4P/P5PK/5N2 w – – 0 31

31. Qb3? …

A totally understandable, but wrong move. White should play 31. Ne3, defending g2 and also planning to transfer his knight to c4. Of course he was wary about 31. … Qb2, with the threat of … Qf2, but after 32. Qa4! Black doesn’t have time to carry out his plan. If 32. … Qf2 33. Qe8+ leads to a draw by repetition.

As you get closer to the endgame, it becomes more and more important to consider each possible piece trade carefully, because each trade will strongly affect the kind of endgame you get into. With the queens on, White has many more aggressive resources. I already mentioned the possibility of saving a draw by perpetual check. If Black does nothing, then White has attractive possibilities like Qa6 or Qa4 followed by Nc4. The knight on c4 is a great piece for both attack and defense, and probably White stands better if he can get it there.

Trading queens has one benefit: White no longer has to worry about being checkmated. But he also gets into a very passive endgame with no real counterplay. His knight does not get to c4, because he is obliged to put a pawn there.

I think that Harmon probably didn’t realize quite how bad his position was going to be after the queen trade. In fact, within a few moves he is close to being in zugzwang.

31. … Qxb3 32. ab Ne2 33. c4 Kf7 34. Nd2 …

Already White is nearly paralyzed. None of his pawns can move, his king is trapped in the corner, and his knight is limited to defensive duties.

34. … Kf6 35. Nf3 Nd4 36. Nd2 Kg5 37. g3 …

Finally giving his king some breathing room.

37. … hg+

This move is okay, but the computer likes 37. … Kh5! a little better. We’ll discuss this after the next diagram.

38. Kxg3 …

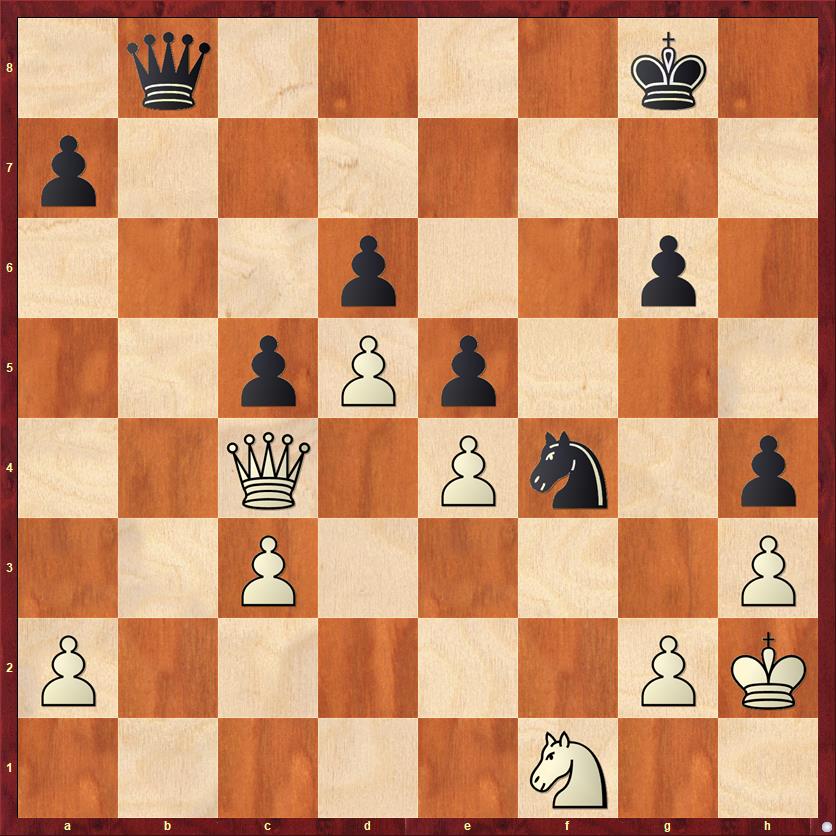

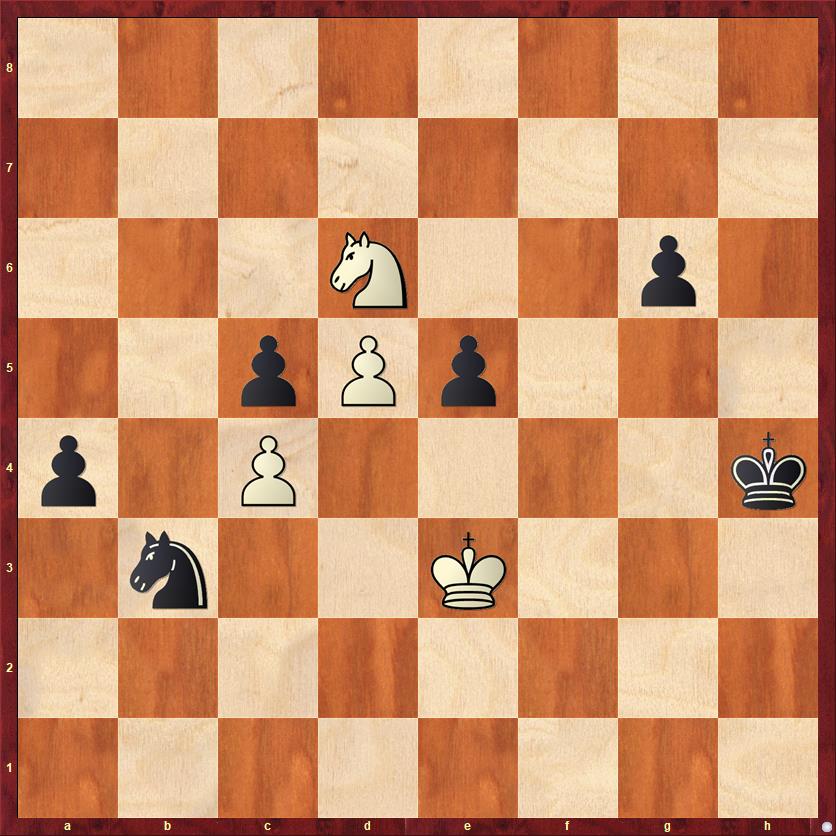

FEN: 8/p7/3p2p1/2pPp1k1/2PnP3/1P4KP/3N4/8 b – – 0 38

After 38 moves, the outcome of the game is decided in the next move pair.

38. … Ne2+??

Thirty-seven good moves go to waste because I don’t understand the endgame. After this move, the computer’s evaluation of the position goes from +3.8 pawns in favor of Black, to 0.0 (drawn).

First, let me acknowledge one thing. Knowing the way that I (mis)manage my clock, I’m almost sure that I was in time pressure by now, two moves before the time control. It’s quite possible that my opponent was also — I just don’t know. However, this is in no way an excuse for making blunders. If you can’t play accurately in time pressure, then you shouldn’t get into time pressure.

How are we to find the right move for Black? It’s not too hard. The first point is that knight and pawn endgames are a lot like king and pawn endgames — the main difference being that the knights move twice as fast. What I didn’t realize is that this position IS a king-and-pawn endgame. With my previous moves I have totally tied White’s knight down so that it can’t move. My knight is on its ideal square, so I shouldn’t want to move it. Because White’s knight can’t move and Black’s knight doesn’t want to move, we essentially have a king-and-pawn endgame.

If we just pretend that the knights aren’t there, Black’s move is totally obvious. You play 38. … Kh5, White’s king has to move away from g3, and then you play 38. … Kh4 followed by pushing the g-pawn. Well, actually I’m lying a little bit. If the knights weren’t there, Black would have to worry seriously about the pawn break b3-b4. But for now, I’m just thinking schematically. My point is that triangulation with the king is a standard maneuver in king-and-pawn endgames, but I somehow didn’t think of applying it in a knight-and-pawn endgame.

So 38. … Kh5! is the right move here. But there are a few complications that are worth mentioning. After 39. h4 Black still has to figure out a way to break through White’s blockade, and the solution is far from obvious. The natural move 39. … g5? is too hasty, because White has the timely resource 40. hg Kxg5 41. Nf3+! Nxf3 42. Kxf3 and if 42. … Kh4? White saves the game with 43. b4! Remember, once the knights are off the board this is a serious threat!

The computer finds an ingenious solution that I almost certainly would not have found at the chessboard, particularly in time trouble: 39. … a6! 40. Kh3 a5! 41. Kg3. The purpose of Black’s last two moves was simply to gain a tempo, getting the pawn to a5 in order to prevent White’s b3-b4 pawn break. Now 41. … g5 is completely winning. After 42. hg Kxg5 Black has the opposition and continues to play it like a king-and-pawn endgame.

While this is a wonderful line, one has to ask whether Black had a way of winning that would not require such ingenious moves. The answer is yes, sort of. On the previous move, after 37. g3, I could have played 37. … Kh5! right away. This is again a tempo-gaining move. If 38. g4+ then Black plays 38. … Kg5 and marches his king right into the heart of White’s position on the dark squares. So White has nothing better than to “pass” with 38. Kg2. But now Black plays 38. … hg 39. Kxg3 g5, gaining a tempo over the above paragraph, so that 40. h4 is now not even possible.

I think it’s really instructive to see all of these subtle tempo-gaining maneuvers. This sort of subtle reasoning is the first thing that goes out the window when you get into time pressure.

Now, as I said, Harmon may have been in time pressure too, because he immediately boots the game back to me.

39. Kf3?? …

Ordinarily this move would be automatic, but the problem with it is that the king is now sitting on the square that the knight would like to move to. The game-saving move was 39. Kf2!

In my post-game analysis I realized that this would have been a much better drawing attempt than 39. Kf3. I wrote, “The last chance to put up serious resistance was 39. Kf2! Nf4 40. Nf3+ Kh5 41. Kg3,” and then I gave long analysis to prove that Black was still winning. However, I missed the fact that 41. h4! draws. The point is that after 41. … Kg4 42. Ng5! Black has let White’s knight out of its prison. Now it is free to go after Black’s Achilles’ heel, the d6 pawn. The computer evaluates the position after 42. … Kxh4 43. Nf7 g5 44. Nxd6 as equal, and I see no reason to doubt this evaluation.

Both sides failed in this endgame because of a lack of schematic thinking. I had to realize that by tying down White’s knight, I had essentially transformed the position into a king-and-pawn endgame. Harmon had to realize that as long as his knight is stuck at d2 the position is hopeless, and his only hope for saving the game is to make the knight active — something that my mistake on move 38 made possible.

After the exchange of blunders, Black is once again winning. Here is the finish:

39. … Nf4 40. Kg3 Nh5+ 41. Kg2 Kf4 42. Nb1 Nf6

Actually, 42. … Kxe4 is also winning, but with the time control past I was now being more careful. I wanted to take the e-pawn with my knight so that he would not be able to win my d6-pawn.

43. Nc3 a6

Again playing carefully and keeping the knight out.

44. Na4 Nxe4 45. h4 Kg4 46. Nb6 …

Now I got a little bit incautious. The safe and sound route is 46. … Ng3 47. Nc8 Nf5, which keeps the d6-pawn defended and frees the e-pawn to advance. White’s h-pawn is a goner, too, but I can take my time rounding it up. However, the temptation of winning the h-pawn right away was too great, and I played

46. … Kxh4?! 47. Kf3 Nd2+?

Now I’ve done the one thing I shouldn’t have done — I’ve allowed him to win my d-pawn. The reason was that I thought I could take his b-pawn and still get my knight back in time to stop his d-pawn. But as we’ll see, I slightly miscalculated. Now the game gets exciting again (which is not a good thing for me).

48. Ke3 Nxb3 49. Nc8 a5 50. Nxd6 a4

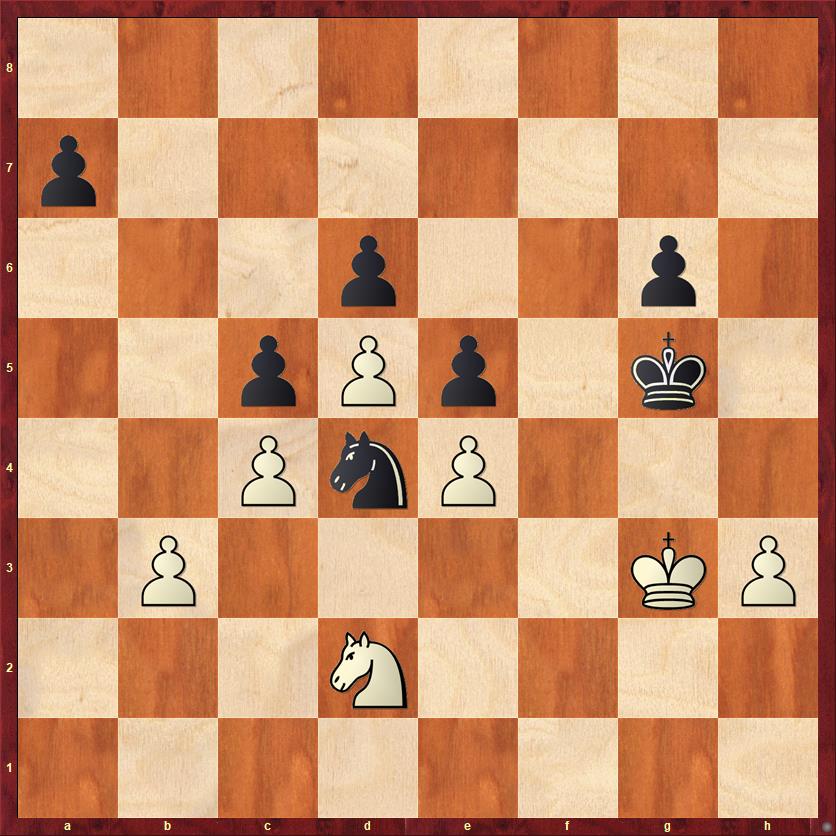

FEN: 8/8/3N2p1/2pPp3/p1P4k/1n2K3/8/8 w – – 0 51

In this position, I was thinking that White would play 51. Ne4 or 51. Nb5, after which I would play 51. … Na5 and be able to stop his d-pawn. I completely overlooked his next move, which forces me to go into a pawn race where I queen first, but White queens with check.

51. Nb7! …

Always keep fighting to the bitter end. More than twenty moves after White blundered by trading queens, we are going to get the queens back.

51. … a3 52. d6 a2 53. d7 a1Q 54. d8Q+ g5

Frankly, I’m just lucky that after the pawns promoted, my king was in a position where he could get away from White’s checks very easily. Now after 55. Qh8+ Kg3 the checks are over. Instead White tries to get his knight back into the action, but it’s too little, too late because White’s king is already almost in a mating net.

55. Nd6 Qe1+ 56. Kd3 …

Forced, because of 56. Kf3 Nd2+ 57. Kg2 Qf1+ 58. Kh2 Nf3 mate.

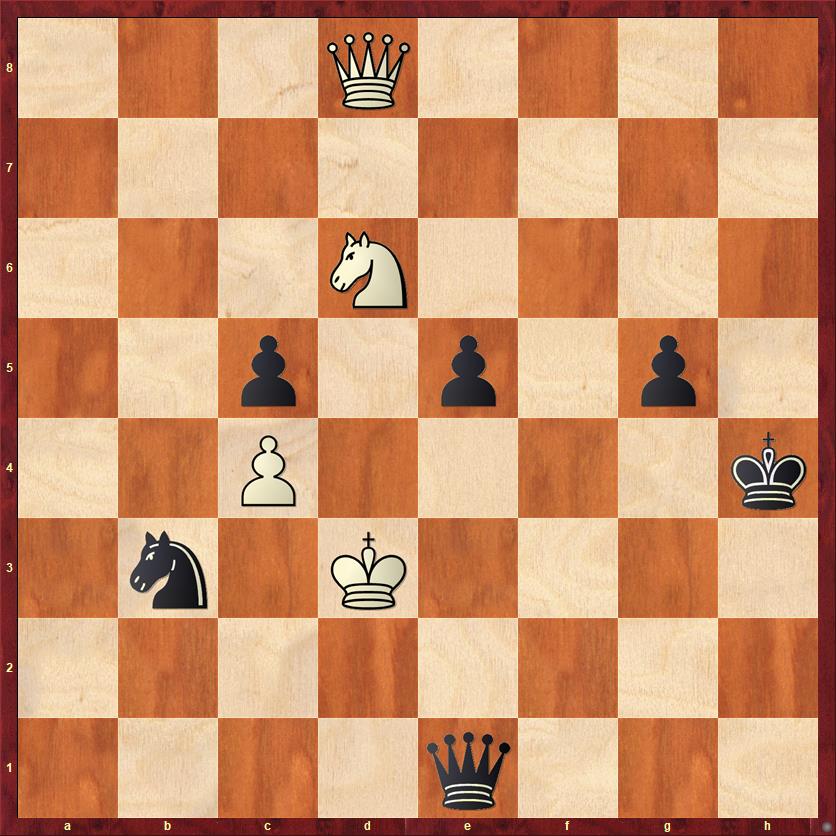

FEN: 3Q4/8/3N4/2p1p1p1/2P4k/1n1K4/8/4q3 b – – 0 56

Now we get a really cute finish, based on one of my favorite motifs in the endgame. When both sides queen in a pawn race, it’s amazing how often one of the queens is able to win the other queen by an x-ray check. This position is an unusually elaborate version of that motif.

56. … e4+! 57. Kc2 …

The main line was 57. Nxe4 Qd1+, with the aforementioned x-ray check. Harmon doesn’t want to give up his queen, but the alternative is walking into another mating net.

57. … Nd4+ 58. Kb2 Qb4+ 59. Ka1 Qa3+ 60. Kb1 Qb3+ White resigns

Whew! That was a close call at the end. This game disproves the old adage, “The winner of a chess game is the player who makes the next-to-last mistake.” Here my opponent made the next-to-last mistake (39. Kf3) and I made the last mistake (47. … Nd2+) but I lived to tell about it. Technically, I suppose you could argue that my 47th move was not a mistake, just an alternative way to win. But I know that the game variation was unplanned, so therefore it was a mistake.

After this tournament, my USCF rating reached its all-time high of 2257. In my diary I wrote, with my characteristic optimism, “I have been playing well enough that I feel that it is a reasonable goal to reach 2300 by the end of the year.”

Alas, it is now 27 years (minus two days) since I wrote those words, and I have yet to achieve that goal. Looking at my games from this period, I really don’t feel as if I had the strategic soundness to get to 2300. I was playing with a lot of energy and chutzpah (see 13. … b5!?) but in positions that required finesse I was playing with a lack of subtlety (see 38. … Ne2+).

In any case, something happened later in 1994 that totally derailed not only my chess plans, but my plans for life in general. After many warning signs that I did not heed, I got word on April 26 that I had been denied tenure by Kenyon College. As I wrote in my diary, “The difference between being guillotined and being denied tenure is that after being denied tenure, you’re still alive. However, the sense of incredulity is still the same. You mean this is really happening? You mean there’s nothing I can do?”

As it turned out, there was something I could do. Any university will have a formal grievance system for challenging decisions like this. I talked with my friends and colleagues, and especially I listened to my wife, who was incensed that after four years of telling me I was a shoo-in for tenure, the college would pull the rug out from under me (and us) in the fifth year. She was right — something didn’t quite add up. I decided to file a grievance, and in September the faculty grievance committee ruled in my favor.

In essence, the grievance committee said two things. First, the administration had not followed proper procedures — which astounded me, because one would think that they would follow all the procedures to the letter, especially in a case that might be challenged. Specifically, they were supposed to get 16 letters of recommendation from students. They only got 15 and they never informed me, so I was deprived of the chance to solicit more letters (which might have been favorable). Second, they said that the president and provost had grossly misinterpreted the contents of the student evaluations they did receive, characterizing them as unfavorable.

So at the end of the year I was still “alive,” but in a really strange situation. I was starting to look for other jobs, while at the same time going through another tenure evaluation, one in which my teaching would come under even more close scrutiny, because that was what the president and provost had found to be deficient. A crucial point was that my department was never informed about the actual content of the student evaluations. Thus they continued to be under the impression that the evaluations had been poor, as the president and provost had said, rather than neutral to positive, as the grievance committee had said. The whole tenure process at Kenyon was rife with secrecy, and that would come back to haunt me.

By the way, this is a very condensed version of the saga. Anyone wanting to read the whole story can find it here, at my main website.

With all this going on in my life, my chess suffered. In the Columbus Invitational, played just a month after the tenure decision, I had a disastrous result of 2 1/2 – 6 1/2, plunging my rating back below master level. I continued to have up and down performances for the rest of the year. Maybe I shouldn’t have been playing chess under the circumstances, but sometimes I am too stubborn.

Lessons:

- Once you learn to think like a master, you can use their thought process against them.

- It may be better to play a risky move that forces your opponent to make difficult decisions, rather than play a less risky move that gives him an easy advantage.

- Especially as you get close to the endgame, piece trades are crucial decisions and should never be played “automatically.”

- If you can’t play accurately in time pressure, don’t get into time pressure.

- Knight and pawn endgames are a lot like king and pawn endgames. In fact, if you can force your opponent’s knight into a purely passive position, you may be able to play the position exactly as if it were a king and pawn endgame.

- In positions where both players have just promoted pawns to queens, watch out for x-ray checks!

- In life, secrecy is a cover for bad decisions. Agreeing automatically to secrecy can be just as bad for you as agreeing automatically to piece trades.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Dana, this game and your+computer analysis are WAAAYYYY above my pay grade, but it was very instructive and playing the game over with ChessBase Reader 2017 is a pleasure because it helps you see all the variations clearly. Still, the play is very deep and subtle. I hope one day I’ll come close to being able to play a game at this level. Again, kudos! Great game and equally great analysis.