As we move to 1992 in my retrospective look at my chess career, I face a dilemma. In 1990 and 1991 I had trouble finding any good games to show you, but in 1992 I have the opposite problem — too many good games. There’s one that, in my notebook, I call a “keepsake.” There’s another one that I lectured about for ChessLecture, and wrote about in Chess Life for the column “My Best Move.” And finally, there is my first win against an International Master. How do I choose among these?

Answer: I don’t. Because I had a couple of years with no games (1980 and 1981), I think it’s fair to make up the shortfall by showing you three games from 1992.

I’ll start with the “keepsake” game. It came in the last round of the Columbus Open, a tournament I did pretty well in. I lost to the winner of the tournament, a Russian emigre named Boris Men, and won my other four games against lower-rated players. “It’s not so easy to win four straight games against people who aren’t a whole lot weaker than you,” I wrote in my diary.

Although I won’t show you my game against Boris Men, I’d like to digress for a moment and tell you his story. He appeared absolutely out of nowhere in 1990 or maybe early 1991, winning tons of tournaments in Ohio and a few in surrounding states. One of his pet openings was the Albin Counter Gambit, which he played in our game. His USCF rating got over 2600, and he was invited to play in the 1992 U.S. Invitational Championship, which took place in Colorado about six months after my game with him.

It’s not often that you have a player in the U.S. Championship whom no one knows anything about. But according to the account I read in Chess Life, the other players quickly figured him out. It turns out that Boris Men was once a strong junior player in the Soviet Union, but then chose a different career (perhaps because he wasn’t quite at the elite level). I think he was possibly a doctor. But when he emigrated to the U.S., he couldn’t get a job at first and fell back on chess to make a living. He had not played competitively in years and years, so all of his openings (except the Albin Counter Gambit) were the latest in Soviet theory — from the 1950s. Once the other players in the U.S. Championship realized this, all they had to do was look up the refutations of those variations that had been discovered in the 1960s. Boris’s goose was cooked. He went 5-10, finishing second to last. He did win games against Roman Dzindzichashvili and Walter Browne, and drew against players like Boris Gulko and Yasser Seirawan, so it’s not as if he was completely overmatched. But he never played in a national-level tournament again.

After my one tournament game against him, I found Men to be soft-spoken and polite. I had gone a little bit berserk, playing a piece sac that wasn’t quite sound, but he kindly said that I had him worried for a little while.

Now let me turn to my “keepsake” game. In the last round of the Columbus Open, I played against an expert named Ken Martin, whom I know nothing about except that he was from Connecticut. This game is not at all complex, but I think that Nimzovich would be proud of it. It beautifully illustrates the the themes of restraint and blockade, and in the final position Black’s pieces are almost comically helpless. It might make a good game for teaching.

Dana Mackenzie — Ken Martin, 6/21/1992

1. d4 f5 2. e4 …

I have always played the Staunton Gambit against the Dutch Defense. Modern Chess Openings, which was my reference at the time, said that it is “without doubt sound as gambits go.” But in a way, its soundness is also its Achilles heel. Black only gets in trouble if he tries to hang onto the pawn. If he gives it back, he can equalize pretty easily.

2. … fe 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Bg5 Nc6

This is the standard, equalizing book line. The knight is actually heading to f7! A very common beginner’s mistake is 4. … d5?, which loses the pawn back to 5. Bxf6 ef 6. Qh5+ g6 7. Qxd5, with a very pleasant position for White. (If Black trades queens, White will win another pawn.)

5. d5 Ne5 6. Qd4 Nf7 7. Bxf6 ef 8. O-O-O!? …

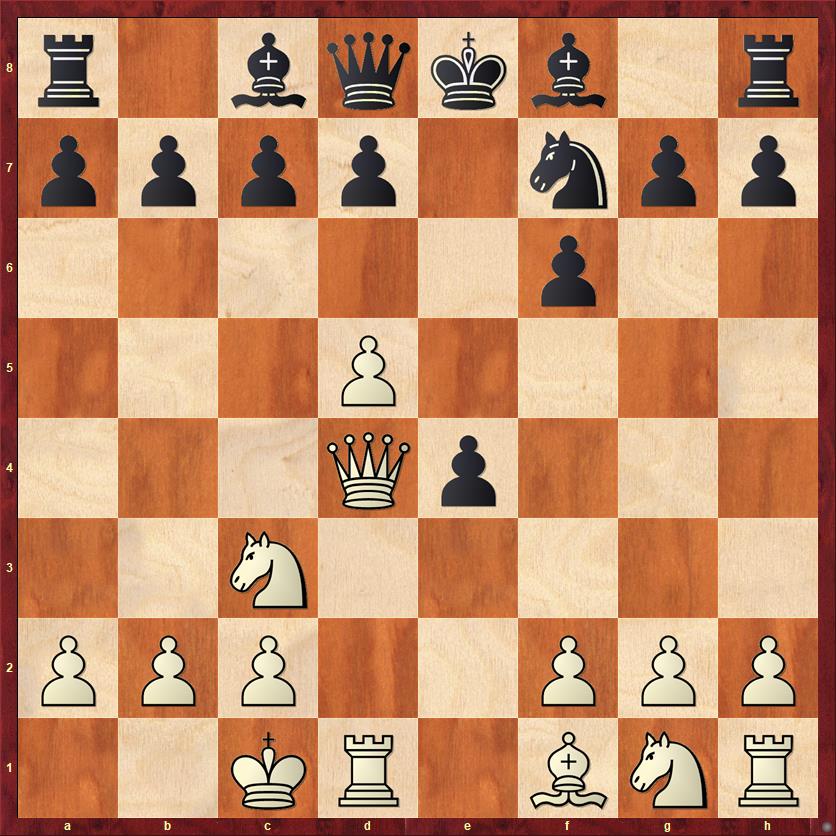

FEN: r1bqkb1r/pppp1npp/5p2/3P4/3Qp3/2N5/PPP2PPP/2KR1BNR b kq – 0 8

This is as far as I knew the theory; I was now on my own. My idea with 8. O-O-O was to try to lure my opponent into defending with 8. … f5, which I thought would loosen his position up. Nevertheless, the computer says that that is what Black should do, and after 9. f3 Be7 10. fe Bf6! Black is okay because White has trouble finding a comfortable square for his queen.

8. … Bd6

You can’t really call this a blunder. And yet — everything that went wrong for Black in this game stems from this move. On d6, the bishop interferes with the development of Black’s queenside pieces, which eventually get completely severed from the rest of Black’s army.

9. Qxe4+ Qe7 10. Re1 …

I was doing my best to keep Black from castling, but maybe he doesn’t have to! After 10. … Qxe4 11. Rxe4+ Kf8! Black continues with … b6 and … Bb7 and … Re8, with a very compact and solid position. I think that a more “conventional” developing move like 10. Bd3 or 10. Nf3 might have been better.

Fortunately, Black makes a worse mistake — actually two moves in a row that just give away two tempi.

10. … Ne5?! 11. Nh3 Ng6 12. Bd3 Qxe4 13. Nxe4 Be5

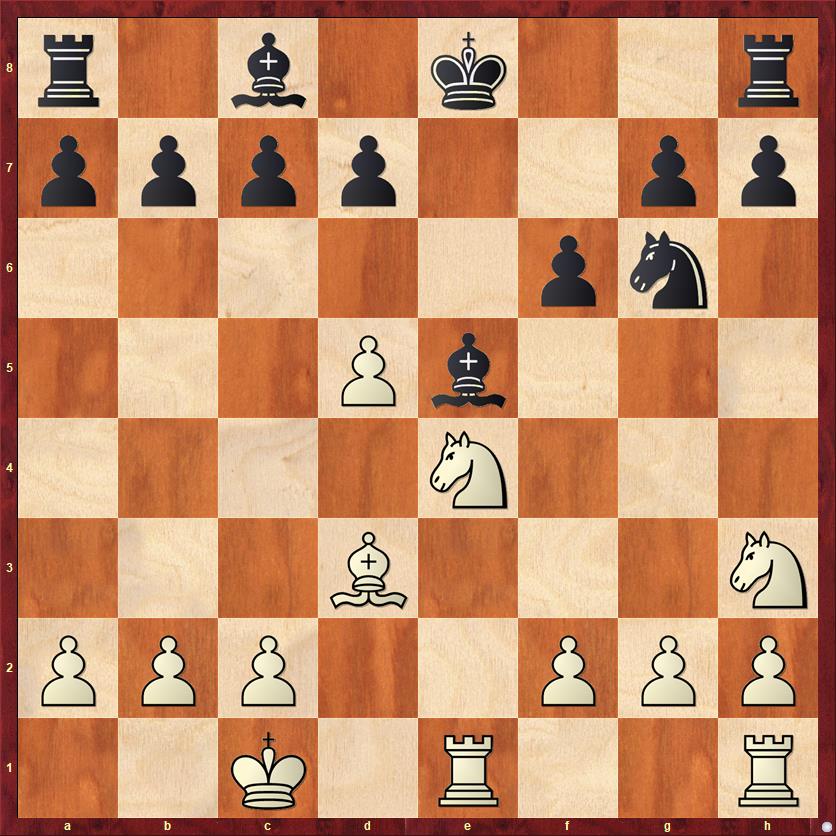

FEN: r1b1k2r/pppp2pp/5pn1/3Pb3/4N3/3B3N/PPP2PPP/2K1R2R w kq – 0 14

One of my quirks — I’m not sure whether it is a weakness or a strength — is that I’ve always been fascinated by the challenge of queenless middlegames. How do you build an attack without a queen? Maybe I should write a book called “No Queens? No Problem.”

In this position, White has an enormous advantage in time. I’ve completed my development and castled, while Black’s queenside is still completely undeveloped and his king is still in the center of the board. However, translating this advantage into concrete threats is not so easy. As noted before, I don’t have a queen to attack with. And Black has no real weaknesses, except perhaps the a2-g8 diagonal, but he’s getting ready to close that diagonal on the next move with … d6.

That is the motivation behind my next move. It sweeps open the a2-g8 diagonal, while blockading Black’s d-pawn and forcing Black to find some other way of getting the queenside pieces out.

14. d6! …

It’s interesting that the computer comes up with a different good move here: 14. f4! The point is that 14. … Nxf4 15. Nxf6+! exploits the pin along the e-file. I think that I completely overlooked this possibility; at any rate, I didn’t mention it in my notes to the game (which were written before the computer era). The move I played is just as good, but played with a different philosophy. The move 14. f4! is in the Alekhine style, seeking to take advantage of White’s lead in development with tactics. The move 14. d6! is in the Nimzovich style, seeking to blockade the opponent and interfere with the communication between his pieces. As you’ll see, it worked extremely well, although I did have a little bit of help from my opponent.

Also, let me say that the fact that White had two good plans, which were quite different from each other, is not a huge surprise because Black has fallen so far behind in tempi.

14. … O-O 15. Bc4+? …

This move, surprisingly, is a mistake. I never realized it until today, when I had my computer look at the game. In retrospect, it’s so obvious. The move I really want to play is 15. g3, to follow it up with 16. f4. There is absolutely no reason to play this “spite check” first, and a good reason not to play it, which you’ll see in a second.

15. … Kh8 16. g3 b5!

A nice, alert move by my opponent. White of course doesn’t want to take on b5, which would give Black an instant attack after … Rb8. The problems with 15. Bc4+ were: 1) it put my bishop on a square where Black could attack it with a gain of tempo. 2) It weakened my control over e4.

17. Bd5 c6 18. Bb3 a5 19. a3 a4 20. Ba2 Bb7?

Until this move, Black was doing pretty well. I would not have played 19. … a4, because it gains nothing and commits Black to an inflexible pawn formation. Even so, Black would still have a perfectly playable game after 20. … Bd4.

It’s ironic, after I criticized Black earlier for developing too slowly, that I’m going to criticize him here for developing the light-squared bishop too quickly. His mistake was comparable to my mistake on move 15. In any position, you should ask yourself, “What does my opponent want to do?” It was really clear to me, at least, that White would love to sink his knight on c5 and blockade Black’s queenside pawns. So Black had to anticipate this and prevent it, while he still could, with 20. … Bd4. This also makes sense from the point of view that Black’s bishop is not really useful on e5 any more. White’s pawn on d6 will be solid after Rd1, which is probably coming next move. So Black should look for greener pastures for his dark-squared bishop — again, while the opportunity lasts. Because it’s not going to last much longer.

From what I’ve just said, my response is probably obvious.

21. Nc5! …

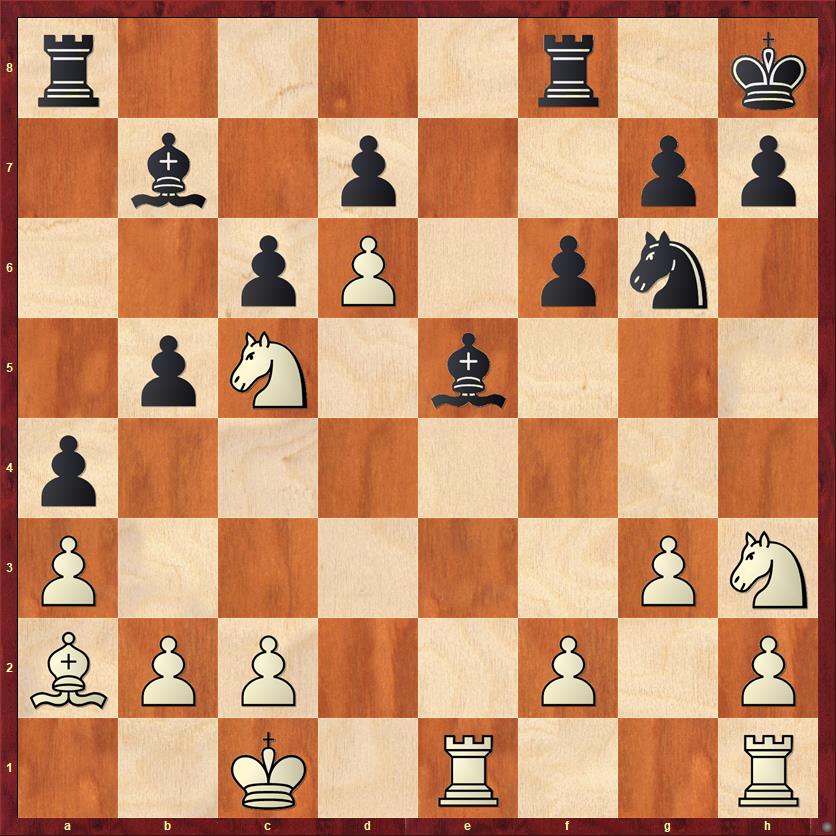

FEN: r4r1k/1b1p2pp/2pP1pn1/1pN1b3/p7/P5PN/BPP2P1P/2K1R2R b – – 0 21

I stick to my Nimzovichian strategy of blockade, blockade, blockade. Of course Black cannot play 21. … Bxd6?? 22. Nxb7 because the bishop has no place to move to that would keep White’s knight trapped.

However, Black can and should play 21. … Bd4! In my notes (again, written before the computer age) I devoted reams of analysis to 21. … Bd4 22. Nxb7 Rfb8?! Now White’s knight is trapped, but Black has trouble actually winning it because of his back-rank weakness after 23. Re4 Bb6 24. R1e1. The only move where I couldn’t find a forced win for White was 24. … Nf8!, but White has a nice positional advantage after 25. Nf4 Rxb7 26. Nd3, with ideas of bringing a rook to e7.

However, it’s all moot because the computer found an improvement for Black: 21. … Bd4 22. Nxb7 Ra7! Now after 23. Re4 Bb6 24. R1e1 there are no mate threats, and Black can calmly play 24. … Rxb7 with equality.

However, my opponent was not a computer but a human expert. He saw his bishop hanging on b7 and his pawn hanging on d7, and thought there was only one solution.

21. … Bc8??

After this move Black’s position is absolutely dead. The rest of the game is basically a mathematical proof of that fact. Of course, my favorite subject is math, so I quite enjoy the rest of the game — even though it is extremely one-sided.

22. Rd1 …

Threatening to win the bishop with f2-f4, so Black’s move is forced.

22. … f5 23. Ng5 …

On h3, this was White’s worst piece. Now it becomes one of his best! In fact, it’s the piece that eventually delivers checkmate.

23. … h6 24. Nf7+ Kh7 25. h4 Bf6

Black would like to exchange off my knight with … Ne5, but of course I don’t want to allow that.

26. f4 …

Prophylaxis, another important Nimzovichian concept.

26. … h5 27. Ng5+ Kh6 28. Rhe1 Nh8

This knight will never emerge.

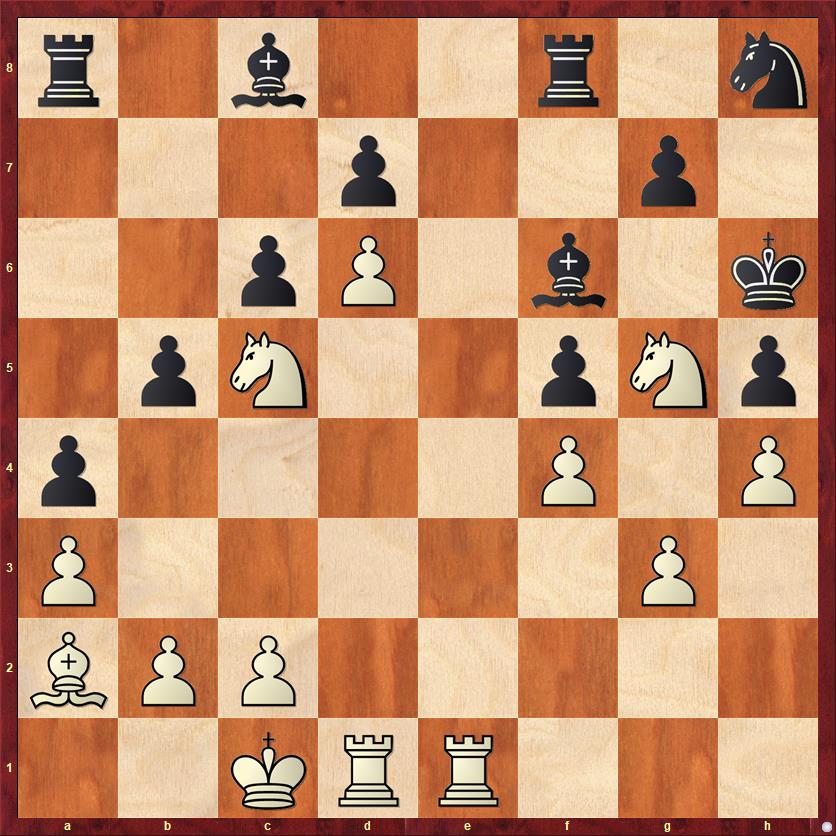

FEN: r1b2r1n/3p2p1/2pP1b1k/1pN2pNp/p4P1P/P5P1/BPP5/2KRR3 w – – 0 29

Black’s position is a sorry sight indeed. The bishop and knight stuck on the back rank. Rooks unconnected. In fact, his whole army has fallen into two camps, the queenside and the kingside, and neither one can do the slightest thing to help the other.

It’s super-tempting here to play the exchange sacrifice 29. Re7, and the computer in fact says that it’s sound. But I thought: Why bother? Three are no risks to me at all in this position. I can just take my time, play some more prophylactic moves, and get all of my pieces ready for the final breakthrough.

29. c3 …

Prophylaxis. Shutting down … b5-b4 (although maybe Black should play this anyway), and also preventing … Bd4 so that I can double my rooks on the e-file.

29. … g6 30. Re3 Kg7 31. R1e1 Ra7

And now, with everything in place, we can proceed with the final combination. The fact that it’s an exchange sac is irrelevant; the important thing is that it removes Black’s only effective defender, the bishop. All of Black’s other pieces are like ghosts. They’re there on the board, but have no ability to affect the action.

32. Re7+! Bxe7 33. Rxe7+ Kf6 34. Nh7 mate

Yes, he did indeed play all the way to checkmate.

Lessons:

- Blockade.

- Prophylaxis. See what your opponent wants to do (even before he does!), and keep him from doing it.

- You can play a mating attack without queens.

- Beware of “automatic moves.” My one bad move this game, on move 15, was a check that I played automatically, without really thinking about the consequences. A more common kind of mistake is automatic captures (or automatic recaptures), but automatic checks fall into the same category. If the check doesn’t actually gain you anything, there’s no need to play it.

- Be alert for “opportunity moves” — moves that you’ll only get one chance to make, like d5-d6 and Ne4-c5 for White and … Be5-d4 for Black in this game. (Black actually had two chances for that move, but he could have saved himself some grief by playing it the first time.)

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Very well played, Dana. Kudos. Your comments and background stories make playing over the game on my Chessbase Reader 2017 the cherry on top of the guava paste.