Welcome to 2021! One of my resolutions is to somehow, some way, play chess against live, human, in-person opponents before the end of the year. Of course, that depends to a considerable extent on factors I can’t control — the progress of the epidemic and the vaccine — so perhaps I should consider it more a wish or a desideratum rather than a resolution.

For now, the pandemic is still very much with us and I’m not going anywhere. So there is nothing else to do but to continue my journey through the years, starting where I left off a couple of weeks ago, in 1990.

Here’s a little-known fact about getting a master rating: it doesn’t necessarily bring with it the opportunity to play more masters. In a typical open weekend Swiss, when you’re an expert, if you win your first game, or maybe two games, you’re pretty much guaranteed to be paired against a master next round. On the other hand, when you’re a master and you win a game or two, you don’t earn a date against a master. It only means that in round three, you’ll have to play an expert who is on a winning streak. Only in the last round or two of the tournament, if you don’t screw up, you might get a chance to play one or two games against other masters. But if you lose a game or give up a couple draws, you’ll be playing against experts for the rest of the tournament.

That was one of the reasons I decided to travel to Chicago in March 1990 for the U.S. Masters (previously known as the Midwest Masters). It was a tournament with a minimum rating requirement of 2200 to get in. With my rating in the low 2200s, I knew that it was going to be a challenging tournament for me. But it was also exciting to know that I would have the opportunity to play against nothing but masters for seven rounds.

After five rounds I was still winless, with two losses and three draws. But in round six I finally got my first win, and in round seven I was paired against Eric Fischvogt, a life master from Michigan. By winning this game, I ended with an even 3.5-3.5 score, which was quite good for me rating-wise. In fact, after the tournament I reached my highest published USCF rating ever: 2248.

There’s a small technicality to discuss here. A few years later, in 1994, I managed to lift my rating a few points higher, up to 2257. But it didn’t stay there long enough to actually be published in a rating supplement. So I didn’t even realize that I had set a new personal record. It was only several years later, after the USCF put all of its records (post-1991) online, that I found out. I’ll probably discuss my “official” personal record in a later post, but for now I’ll show you the game that (at the time) gave me my highest rating ever.

One small warning: some parts of this game are about as exciting as watching paint dry. And it was unfortunately decided by a blunder at the end. But until that point, I think it was a high-quality game, and even though there was a blunder, I think that the endgame as a whole (including the blunder) is quite instructive).

Eric Fischvogt — Dana Mackenzie, 3/18/1990

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nd4

At this time, the Bird Variation (3. … Nd4) was still new to my opening repertoire, and I was alternating between it and the Modern Steinitz Variation (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 a6 4. Ba4 d6), which I had played previously. My results with the Bird were better, so it has now been my exclusive weapon against the Ruy Lopez for almost thirty years.

4. Bc4 …

This is an excellent and underrated way to play against the Bird. The three grandmasters whom I have faced in this variation all chose this move, and they all beat me. However, Fischvogt did not get any advantage out of it.

4. … Bc5 5. O-O d6 6. c3 Nxf3+ 7. Qxf3 Qf6 8. Qe2 Ne7 9. d3 Ng6 10. Be3 Nf4!

I liked this move then and I still do. Black is fighting for more than just equality.

11. Bxf4 Qxf4 12. Kh1 …

FEN: r1b1k2r/ppp2ppp/3p4/2b1p3/2B1Pq2/2PP4/PP2QPPP/RN3R1K b kq – 0 12

This is a position worth talking about. After the game I was under the impression that Black had an opening advantage, and I tried to figure out why I had not been able to capitalize on it.

Here’s what I wrote: “Perhaps 12. … O-O was too routine. I think Black should not have allowed his bishop to be driven from its active post so easily. Here is a possible plan: … a5, … Bg4 (to provoke f3), … Be6, … h5, … h4, … Qh6, … Be3 and … Bf4.”

I like the fact that I was trying to put together a plan (albeit in hindsight). And it’s good to stop and think about whether castling is really the right thing to do; we shouldn’t castle automatically, just as we shouldn’t do anything in chess automatically. Our decisions should have good reasons. Is there anything to my idea of leaving the king in the center, or perhaps even castling queenside, and launching a kingside pawn charge?

To answer this question, let’s think about the nature of Black’s so-called advantage. Do I have a better pawn structure? No. Am I ahead in development? No. Has White made any questionable moves? No. The move he just made, 12. Kh1, is a little bit slow but it is normal prophylaxis, enabling him possibly to play f3 or even g3 and f4 at a later time.

There is one and only one thing that might give Black an advantage here: the two bishops. But going all-out for a pawn thrust on the h-file does not make use of that advantage. I do like the beginning of the plan I wrote. I like the idea of … a5, to keep my dark-squared bishop on the a7-g1 diagonal. I like the idea of … Bg4, provoking f2-f3. If I can accomplish that, I have done something to enhance the power of my bishops, specifically the dark-squared bishop. As long as that bishop is staring at g1, the square right next to White’s king, that king is never going to be completely comfortable. I want you to compare this variation with what actually happened in the game, where my dark-squared bishop never really lived up to its potential.

The other thing that Black’s position needs is flexibility. We have to be objective: neither side really has much of an advantage yet. So we need to develop our pieces in a way that gives us lots of different plans of action. The plan I outlined in my note, committing everything to a quixotic “attack” that doesn’t even accomplish anything, is the opposite of flexible. It’s putting all of my eggs into one basket.

So the bottom line is that I didn’t really do anything wrong here. I was only under the impression that I had done something wrong because I didn’t get enough of an advantage. It’s possible that … a5 followed by … Bg4 and then (if chased by f2-f3) … Be6 or … Bd7 would have been a little better. Castling should also be part of the plan, but I don’t necessarily have to do it right away.

12. …. O-O 13. Nd2 c6 14. a4 Be6 15. b4 Bb6 16. a5 Bc7 17. f3?! …

I think this is the first misjudgment of the game. White should take on e6. The player who controls the pawn breaks controls the game. This move allows Black to carry out both of his desired pawn breaks, … d5 and … f5.

17. … d5 18. Ba2 Rad8 19. Rfd1 Kh8 20. Nf1! f5

Second pawn break accomplished. But it does come with a cost: the queens come off the board.

21. Qe3 Qxe3 …

Sacrificing the a7 pawn with 21. … Qh4? 22. Qxa7 is not a realistic option, because White’s kingside is well-defended and the queen is not at all out of play on a7; it can easily come back all the way to g1 if necessary.

22. Nxe3 …

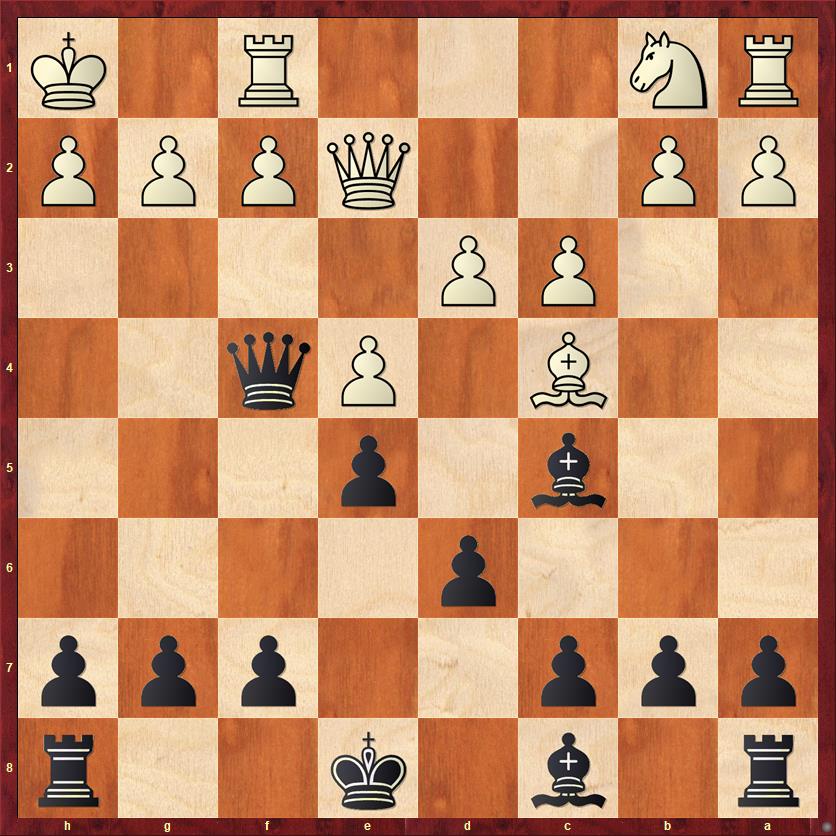

FEN: 3r1r1k/ppb3pp/2p1b3/P2ppp2/1P2P3/2PPNP2/B5PP/R2R3K b – – 0 22

Another good time to pause and assess. Here I think I made a positional mistake. Right now, Black’s white squares are a little bit shaky. The undefended bishop on e6 is worrisome. I would like to retreat it to g8, but then the f5 pawn would hang. So I played what seemed like a natural move,

22. … f4?!

This would be great if we had a King’s Indian sort of position where I could launch an avalanche attack on the kingside. But with queens off the board, that’s not likely to work. The first problem with 22. … f4 is that it more or less permanently establishes my dark-squared bishop as a bad bishop. And the second problem is that it closes the f-file. Before this move, White at least had to worry a little bit about the possibility of a pawn trade on e4 and a rook landing on f2. Finally, just as a general rule, the two bishops are better in a position with open lines, and less effective in a blocked position. For all these reasons, a more flexible move would be 22. … g6, keeping all the options open, followed by … Bg8 and then possibly opening the f-file.

23. Nc2 Bg8 24. c4?! …

I’m skeptical about this move, too. The exchange of pawns transforms the position drastically, and not in a way that helps White. The rooks come off the board, and the pawn on c4 becomes pinned. Probably White is still okay but he’s starting to skate on thin ice.

24. … de! 25. de Rxd1+ 26. Rxd1 Rd8 27. Rxd8+ Bxd8 28. Ne1! …

Aiming for d3, and trying to make Black’s dark-squared bishop into a passive piece.

28. … b6 29. Nd3 Bc7 30. ab ab 31. Nc1 …

Breaking the pin on the g8-a2 diagonal. White can now think about playing c4-c5.

31. … g5

Now and for the next three moves, the computer thinks that White should play c5 and trade bishops while he has the chance. However, both sides are executing the very natural plan of activating their kings, so I don’t think it is worth giving out “?!”s for these moves.

32. Kg1 Kg7 33. Kf1 Kf6 34. Ke2 Bd6 35. b5 …

Now White plays the other pawn break! This might seem like an obvious move, but we’re starting to warm up to the main theme of this game: there is nothing obvious about endgames, and especially king and pawn endgames and the transition to such endgames.

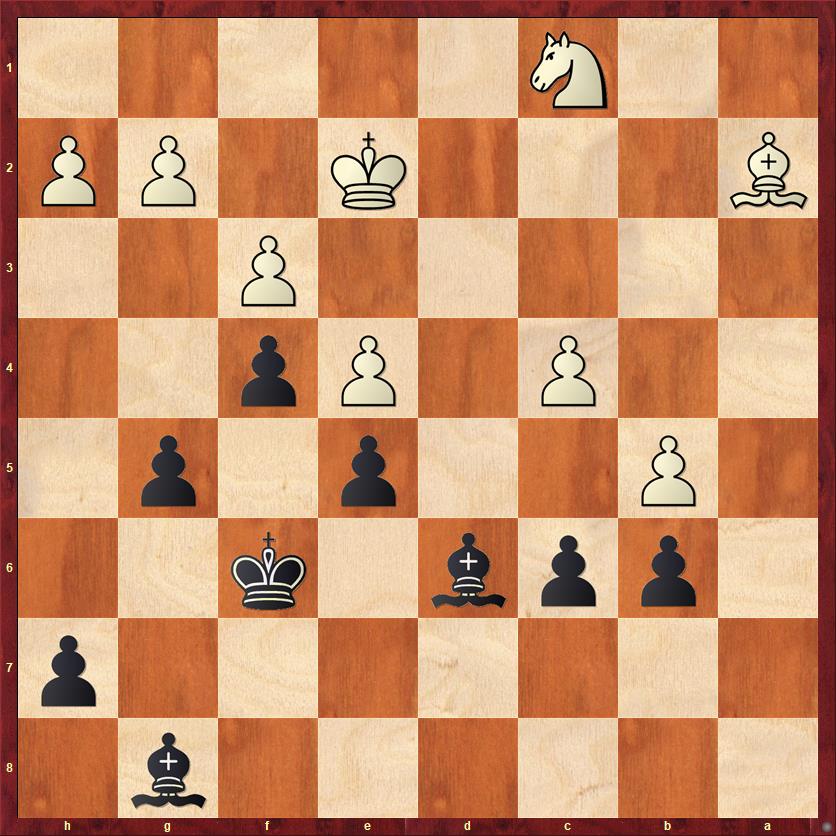

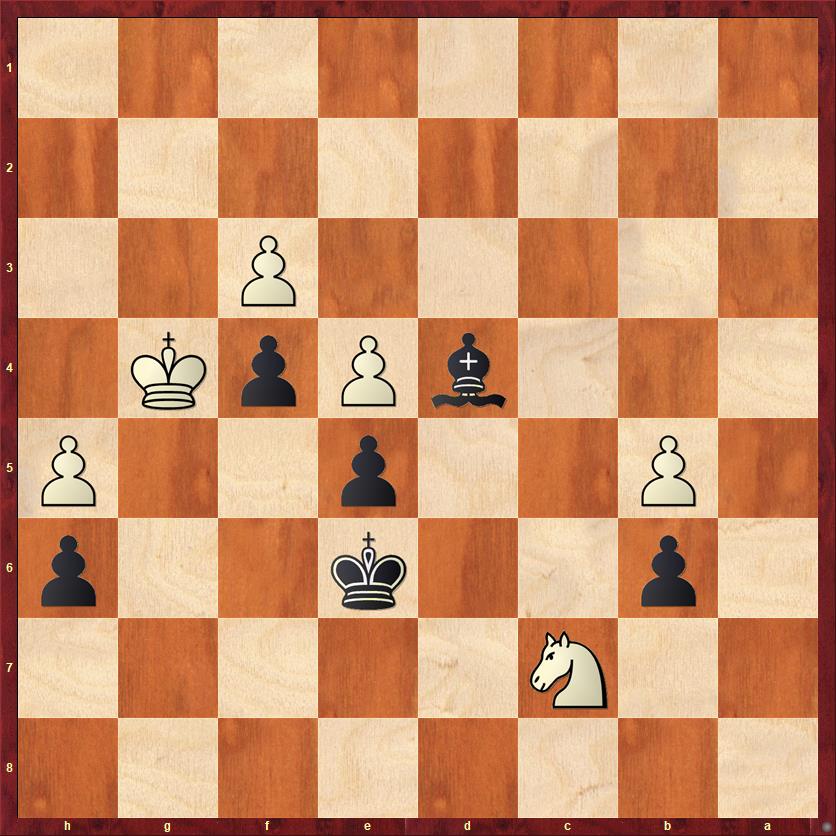

So let me ask you: What is wrong with just sitting on the position with 35. Nd3? You’ll probably say, obviously this is bad for White because 35. … b5 wins a pawn. But let’s go a little bit deeper. After 36. Kd2 Bxc4 37. Bxc4 bc 38. Nc5! it looks as if White will recover the pawn with an easy draw, after 38. … Bxc5 39. bc (diagram).

FEN: 8/7p/2p2k2/2P1p1p1/2p1Pp2/5P2/3K2PP/8 b – – 0 39

This, to me, is one of the most amazing positions that didn’t happen in the game. It seems like an effortless draw for White. Just play Kc3 and Kxc4, and you can start signing the scoresheets.

Well, some of you might say, we can start pushing the kingside pawns with 39. … h5. And you’re getting warmer, but 39. … h5 is still too slow. The h-pawn isn’t the one that is going to queen — it’s the f-pawn! After 39. … h5 the computer says that the position is a draw.

The winning move here for Black is the remarkable 39. … g4!! This is a great example of a theme I’ve been harping on with some regularity recently: sometimes you don’t need to prepare a pawn break. We don’t need to prepare … g4 with … h5. We save a tempo by doing it right away — and tempi are everything in this endgame.

The main line after 39. … g4! goes 40. Kc3 Kg5 41. Kxc4 gf 42. gf Kh4 43. Kb4 Kh3 (watching the lumbering pace of these kings is like watching turtles race!) 44. Ka5 Kg2 45. Kb6 Kxf3 46. Kxc6 Kxe4 47. Kd6 f3 48. c6 f2 49. c7 f1Q 50. c8Q. Both sides promote, but Black promotes first and has an extra pawn, which should be enough to win. Note that if we had wasted a tempo with 39. … h5, then White would have promoted first, and the computer judges it to be a draw.

The other thematic idea after 39. … g4! is for White to accept the pawn sacrifice. But then Black wins very easily with 40. fg Kg5 41. h3 Kh4, and the dark squares are a highway for Black’s king to invade.

I certainly wasn’t aware of any of these possibilities. In my notes, I simply wrote, “35. Nd3? b5 etc.”, which is probably the most superficial analysis in history. I would guess that Fischvogt wasn’t aware of any of this, either. He just played the move he thought was logical. But as Hamlet said, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy,” … or your logic.

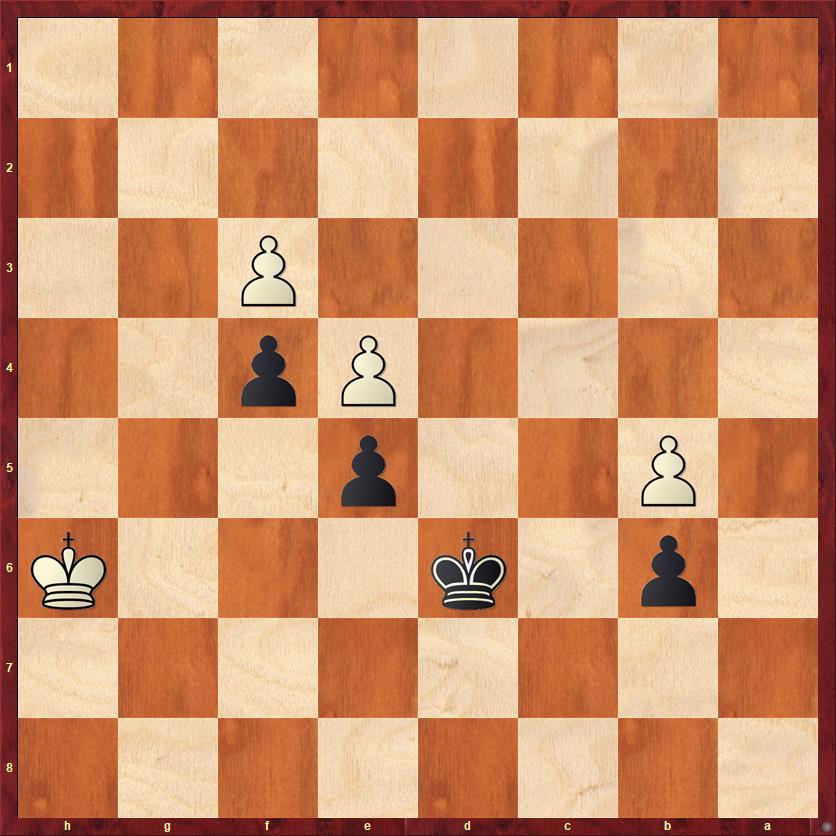

Okay, let’s get back to the game, where Fischvogt has just played 35. b5. This is also a very critical line, where once again there were more things going on than I dreamed of in my philosophy. What should Black play? What is the evaluation?

FEN: 6b1/7p/1ppb1k2/1P2p1p1/2P1Pp2/5P2/B3K1PP/2N5 b – – 0 35

Here I played the extremely lame move 35. … cb?, leading to a trade of white-squared bishops and an endgame of bad bishop versus knight. Even though my bishop is not trapped behind the pawn chain, it’s still a position that I have no hope of winning because the bishop literally can’t attack anything. Meanwhile, it has to babysit all of those dark-squared pawns to make sure they don’t get eaten by the big bad wolf, er, White knight.

You’re probably asking: If Black has no hope of winning, how did I win the game? Shhh. All will be revealed in due time.

A much better winning try was the move 35. … Ba3, when for the first time all game the black-squared bishop is actually attacking something. It was originally my intention to play that move, but then I saw the crazy idea 36. bc!? Bxc1 37. c5! Bxa7 38. cb, when I thought there was no way for the bishops to stop the pawns. But there is! I can play the beautiful scissors maneuver, 38. … Ba3 39. c7 (if 39. b7? Bd6 stops the pawns) 39. … Bc4+! followed by … Ba6. Whew!

So is Black winning? It looks like it … until you start asking whether White has any way to save a tempo. Remember, tempi are everything! In fact, White can save a tempo by playing c5 one move earlier: 35. … Ba3 36. c5! Now Black does not have time to take the knight, because 36. … Bxc1? would be met by 37. cb! and the scissors trick doesn’t work. Black has to settle for 36. … Bxa2 37. Nxa2 Bxc5, which wins a pawn but not the game after 38. bc Ke6 39. Kd3 Kd6 40. Kc4 Kxc6 41. Nc3, establishing a secure blockade.

This is really the way the game should have ended, and if White had drawn this way, I would just have to tip my hat to him for a well-played defense.

The way the game actually ended was… different.

35. … cb? 36. cb Bxa2 37. Nxa2 Bc5 38. Nc3 Ke6 39. Nd5 Bg1 40. g3!? …

I have to give my opponent credit here. He could have played 40. h3, with a risk-free draw. But he was still playing for a win, and as we’ll see, that was eventually his downfall.

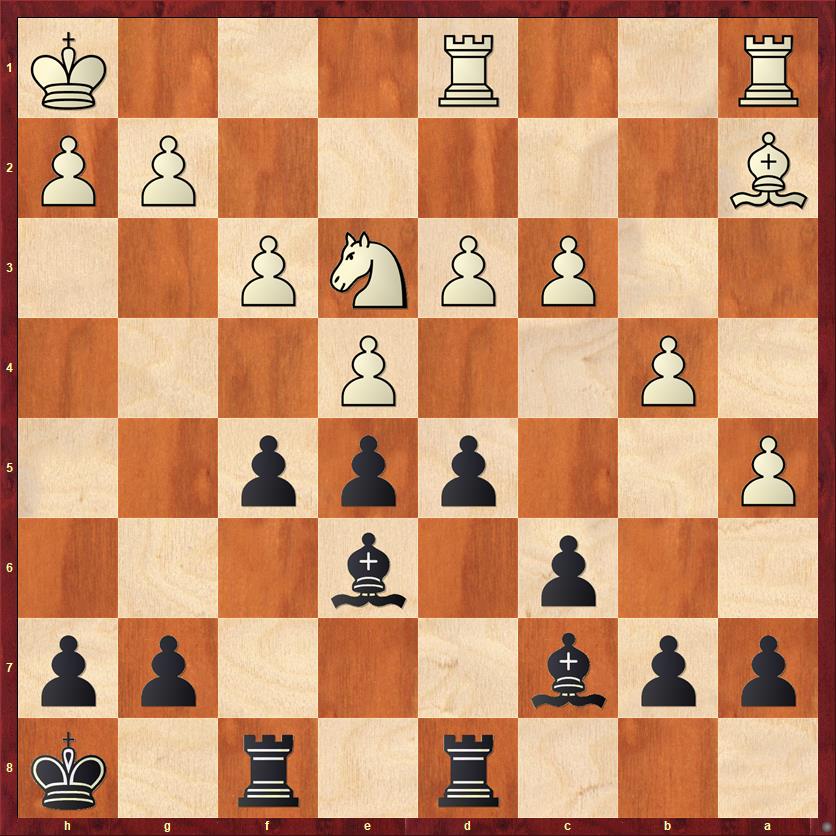

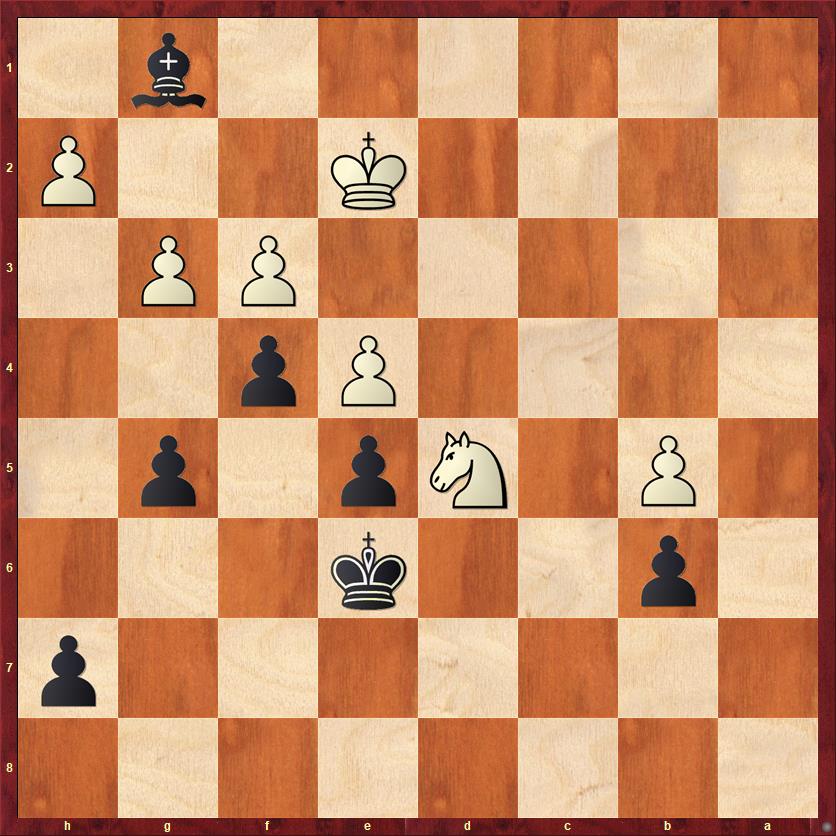

FEN: 8/7p/1p2k3/1P1Np1p1/4Pp2/5PP1/4K2P/6b1 b – – 0 40

40. … Kd6

On the last move of the time control, with my flag hanging, I wasn’t about to take the bait with 40. … Bxh2. This position is still drawn, but it contains the seeds of disaster. Here is one way that everything could go wrong: 40. … Bxh2 41. Nxb6 Bxg3 42. Nc4 h5 43. Nxe5! Kxe5?? 44. b6 Kd6 45. e5+! and White wins. The king cannot stop the two passed pawns, and the bishop is absolutely useless. Wow.

Compared to that exciting variation, the next fourteen moves are, as I said earlier, like watching paint dry. In my mind I had completely conceded a draw, but my opponent kept probing for a way to win.

41. gf gf 42. h4 Ke6 43. h5 Bc5 44. Kf1 h6 45. Kg2 Bd4 46. Kh3 Bc5 47. Kg4 Bd4 48. Nb4 Bc5 49. Nd3 Be3 50. Ne1 Bf2 51. Nd3 Be3 52. Nb4 Bc5 53. Nd5 Bd4 54. Nc7+ …

Now it starts to get interesting again.

FEN: 8/2N5/1p2k2p/1P2p2P/3bPpK1/5P2/8/8 b – – 0 54

A wake-up call for Black! The game hinges on moving the king to the right square.

54. … Kd7!

Not 54. … Kf6?, which would lose to 55. Ne8+ and the knight reaches f5 with a winning fork. A very ingenious trap by my opponent! But he isn’t finished.

55. Kf5?! …

He could just have played 55. Nd5, with a completely routine draw. But he is determined to take every conceivable chance to win the game. Probably this is what life masters do. They’re used to squeezing wins out of positions where ordinary mortals just agree to a draw.

White sacrifices a piece, but I will have to give it back to stop his passed h-pawn.

55. … Kxc7 56. Kg6 Bc5 57. Kxh6 Bf8+ 58. Kg6 Kd6 59. h6 …

Again, White could have a draw for the asking with 59. Kf7 Bh6 60. Kg6. But he is determined to keep on squeezing for a win.

59. … Bxh6 60. Kxh6 …

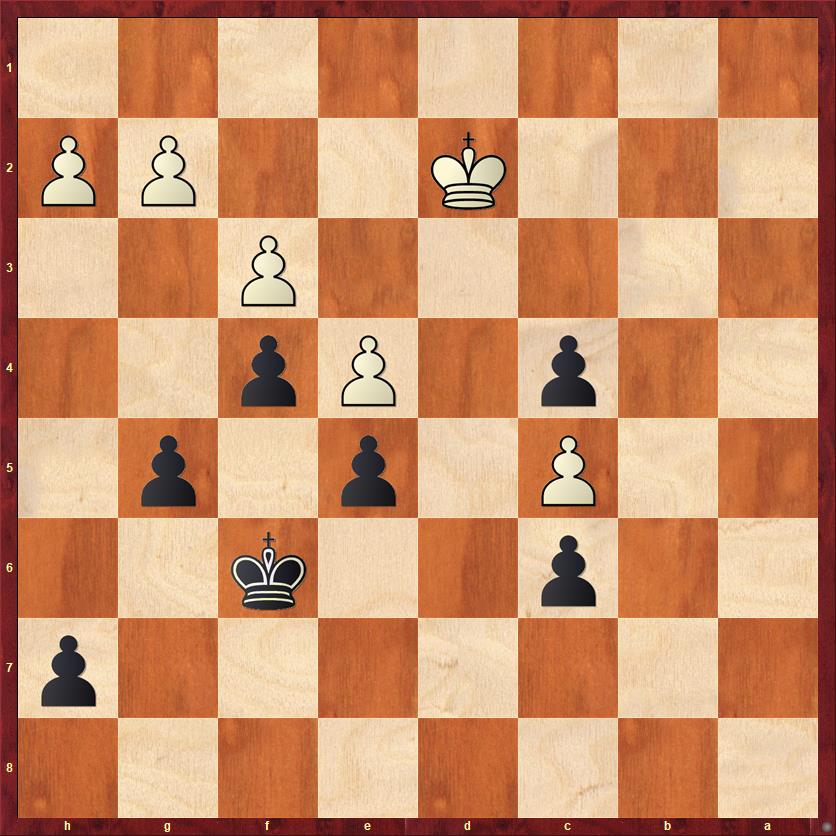

FEN: 8/8/1p1k3K/1P2p3/4Pp2/5P2/8/8 b – – 0 60

And now we have gotten to a king and pawn endgame. King and pawn endgames are where everything seems obvious and nothing is obvious, and where dreams go to die.

60. … Kc5!

No points for 60. … Ke7?? or 60. … Ke6??, when White takes the opposition, shoulders the Black king away from the e-pawn, and wins easily.

61. Kg6 Kxb5 62. Kf5 Kc4! 63. Kxe5 b5 64. Kxf4 b4

It would be interesting to know where exactly White’s thinking went wrong. Did he see this endgame way back on move 55, and think that with K+2P versus K+P it was going to be an automatic win for him? If so, I would be profoundly impressed with the depth of his conception. But… it’s wrong. And now he makes his fatal mistake.

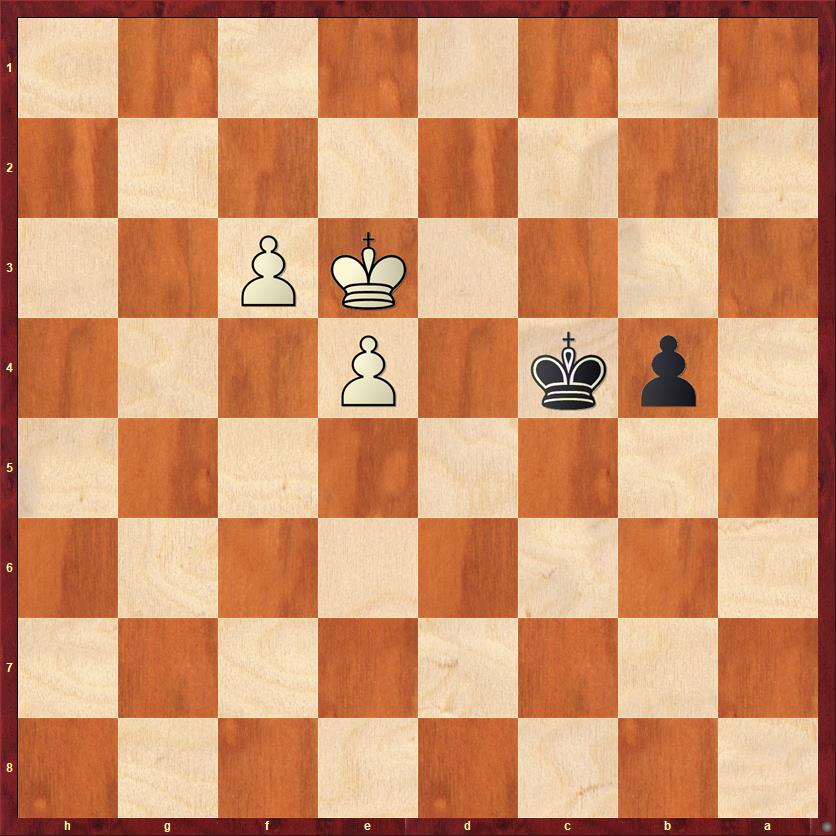

65. Ke3?? …

FEN: 8/8/8/8/1pk1P3/4KP2/8/8 b – – 0 65

The right way to draw was 65. e5! Black of course cannot go for the pawn race: 65. … b3 66. e6 b2 67. e7 b1Q 68. e8Q and according to the tablebases, White mates in 66 moves. So I have to try to stop the pawn with 65. … Kd5. Then White, in turn, needs to avoid a blunder. (Remember what I said about king and pawn endgames never being obvious?) If he tries to advance his pawn with 66. Kf5??, White loses because now Black will queen with check. Instead, it is now time for him to play 66. Ke3!, giving up his e-pawn but getting within the square of Black’s b-pawn. After 66. … Kxe5 it is definitely scoresheet-signing time.

But in all fairness to White, I don’t think that he was ever, ever playing for a draw in this endgame. He was playing for a win. And with this move, he thought he had achieved it. He had a very rude awakening when I played

65. … Kc3!

This move has two points, and he must have missed one of them. The first point is that he can’t stop my pawn with 66. Ke2 b3 67. Kd1 b2, because the pawn itself keeps his king from playing Kc1, and there is no c0 square.

The second point is that he now loses in a pawn race, because 66. e5 b3 67. e6 b2 68. e7 b1Q 69. e8Q loses the queen to an x-ray check after 69. … Qe1+. This is absolutely one of my favorite motifs in king-and-pawn endings, the pawn race ending in a promotion for each player and then an x-ray check.

So…

White resigns.

One small thing I didn’t like about the television series “The Queen’s Gambit” was that Beth Harmon’s opponents never saw that they were losing until the very last move, and then they would stop the clock and stomp off in a huff. In my experience in tournament chess, such an ending is extremely rare. Usually the losing player knows for quite a while that the game is going badly, and usually people at least shake hands after resigning, and sometimes even make a friendly comment like “Good game.”

But this was one game that absolutely fit the “Queen’s Gambit” script. My opponent clearly did not see my last move coming, and he stomped off in disgust, without saying a word. It’s hard to blame him. He resisted the temptation to take a draw over and over again, played this beautiful fifteen-moves-deep conception to get what he thought was a winning position… and then he lost because of an x-ray check. Or he lost because there isn’t a c0 square. Sometimes chess just isn’t fair.

Lessons:

- King-and-pawn endgames are where everything seems obvious but nothing is obvious, and where dreams go to die.

- He who controls the pawn breaks controls the game.

- In a position where neither player has established an advantage, it’s usually best to choose the moves that give you the maximum flexibility.

- Even when it is developed outside the pawn chain, a bad bishop can still be a pretty sad piece because it has nothing to attack.

- In positions with passed pawns or potential passed pawns, one tempo is worth its weight in gold (or at least its equivalent weight in pawns).

- If you think you need to prepare a pawn break before playing it, so as not to lose a pawn, take a closer look. Pawn breaks are often strongest precisely when they are unprepared (because your opponent won’t be prepared for them either!).

- Don’t ever forget the double-promotion-and-x-ray-check trick.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Hi, I stumbled on this page after playing Eric last weekend in August 2022(!). I’m pleased to report he still plays fighting chess. It was a small weekend swiss that attracted a few “Fischer-era players.” PS – I enjoyed kibitzing and chatting with Eric between rounds, but at the board it was all business!