The year 1987 was one when everything started coming together for me in chess. Even now, going over my games and results from that year, it’s gratifying to see the years and years of effort at improvement starting to bear fruit. Of course, there was plenty more for me to work on. In chess, there is always more to work on.

Anyhow, here is a list of all the great things that happened in 1987:

- Second state championship (on tiebreak over Randy Kolvick)

- First master rating (2206 at year’s end)

- Third place in North Carolina Invitational (qualified for by winning state championship)

- First game against a GM (loss to Boris Kogan)

- First game against an IM (loss to John Donaldson)

Notice I include a couple of losses on this list! Even today, sitting down at the board opposite a titled player gives me a rush of adrenaline. It always makes me feel as if this game could be one for the history books. And even if I lose, it will be a free lesson from one of the best in the business.

Let me talk about the first two items on this list. Probably a lot of chess players would be more excited about the National Master title than a state championship, but I felt the other way. Maybe it’s because my sister was a multiple-time state champion in swimming, and I wanted to have a comparable achievement in chess. Winning a second state title was every bit as sweet as the first. Let’s be honest, I thought the first one was a fluke. I wasn’t ready for it yet. But two titles in three years, I thought, could not be a fluke.

By contrast, the NM title was a little bit less thrilling because, as far as I was concerned, I was going to go a lot higher. It’s only in retrospect that I know that I never got past 2257, and I was never even able to maintain my rating consistently over 2200. I’ll talk about the possible reasons in my next post. In retrospect, National Master was the culmination of a journey, but at the time I thought it was just another signpost on the journey.

For anyone who cares about such things, here is how long I spent in each rating category.

- Class D: 1 year

- Class C: 1 year

- Class B: 2 years

- Class A: 6 years

- Expert: 5 years

- From NM title to all-time rating peak: 6 years

So for all you people who have been playing ten years and still haven’t gotten past class A, fear not! It can be done!

Okay, let’s get to one of my most memorable games from 1987: the game that won me a second state title.

The state championship was an open, not closed tournament that year, as organizer Leland Fuerstman bowed to reality and realized that he could get stronger players if people from Georgia and South Carolina and Virginia could come, too. Going into the last round, I was out of contention for first place in the tournament — but I was tied for the top North Carolina player with Randy Kolvick, both of us with 4-1 scores. Appropriately, we were paired against each other in the last round.

Randy was much more of a force in North Carolina chess than me; he was a 2300-plus player, and he would go on to win six championships (1983, 1988, 1989, 1993, 1994, and 1997). The 1997 championship was his last rated tournament. If anyone knows why he quit, I’d be interested in the story. Maybe he just thought that six was enough. Or maybe his “real” career started taking too much of his attention (he worked for IBM). That happens, you know.

But in 1987, we were at one title apiece, and both going for number two. To win the title, I would have to earn it against the best.

Well, I did… and I didn’t. It’s complicated. You’ll see.

Randy Kolvick — Dana Mackenzie

1. c4 c5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. g3 g6 4. Bg2 Bg7 5. Nf3 e5

The Botvinnik Variation was a fairly recent change to my opening repertoire. For years I had played 1. … e5 against the English and generally improvised from there. I somehow didn’t think the opening was worthy of serious study. But then I saw a game Zitzman-Eisen from the 1980 U.S. Correspondence Championship (in the March 1983 Chess Life), where Black won with the Botvinnik with a kingside attack, and I was impressed by how easy it seemed to be.

6. O-O Nfe7 7. d3 O-O 8. a3 d6 9. Rb1 a5 10. Bd2 f5 11. Ne1 Rb8 12. Nc2 Be6 13. b4 …

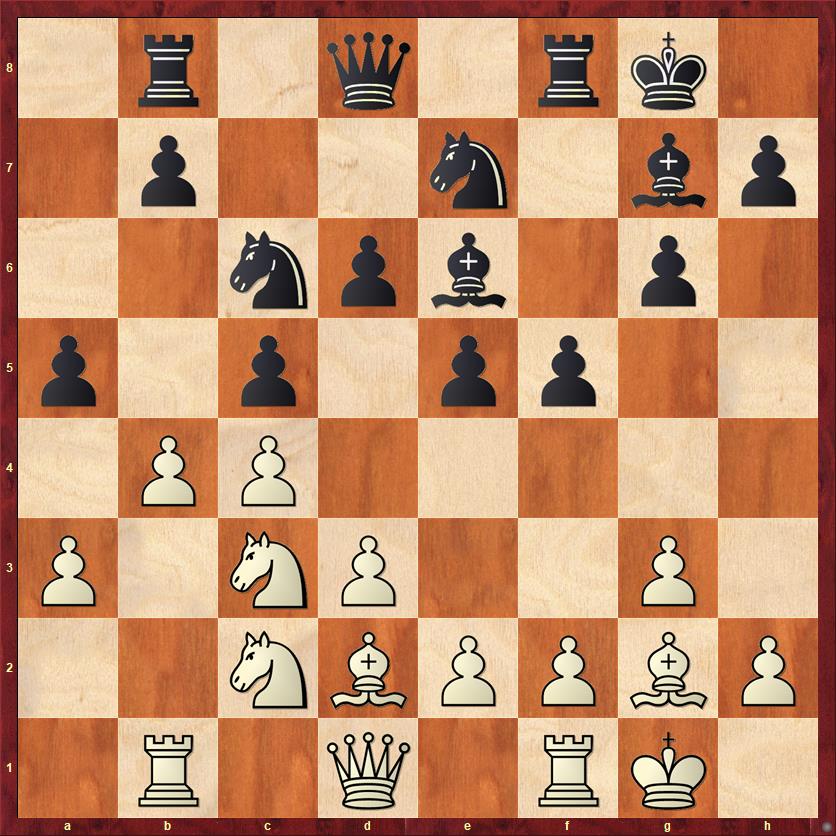

FEN: 1r1q1rk1/1p2n1bp/2npb1p1/p1p1pp2/1PP5/P1NP2P1/2NBPPBP/1R1Q1RK1 b – – 0 13

This is all pretty standard stuff. I wrote in my notebook, “White has spent a half-dozen moves preparing this break [13. b4], and what does it accomplish? Very little, I think.”

Well, obviously I’m not a huge fan of the English Opening. It seems a little bit like sumo wrestling to me. The two sides build up behind their respective walls of pawns (note that no pieces have developed in front of pawns) and they gradually push forward and one of them tries to push the other out of the ring. It’s all a bit ponderous — except that when pawn trades happen and the position opens up, things can get tactical in a hurry. I’m sure that is how someone like Kolvick won his games.

13. … ab 14. ab b6 15. b5 Nd4

The position still seems balanced to me. White’s king bishop now has a beautiful diagonal, but there is nothing on that diagonal. Black’s knight on d4 is impressive, and Black has a fairly straightforward plan of expansion with … d5. With a center like that, how can you lose?

White has two ways to discourage … d5: with Ne3 or with Bg5. He chooses the wrong one.

16. Ne3? …

This is a standard maneuver, but somehow Kolvick has taken too long to get around to it.

16. … f4! 17. Ned5 Nxd5 18. Nxd5?! …

In this case, 18. Bxd5 was the better way to take, but this has to be considered a strategic defeat for White. After he went to all that effort to open the long diagonal for his bishop, now he has to trade it off.

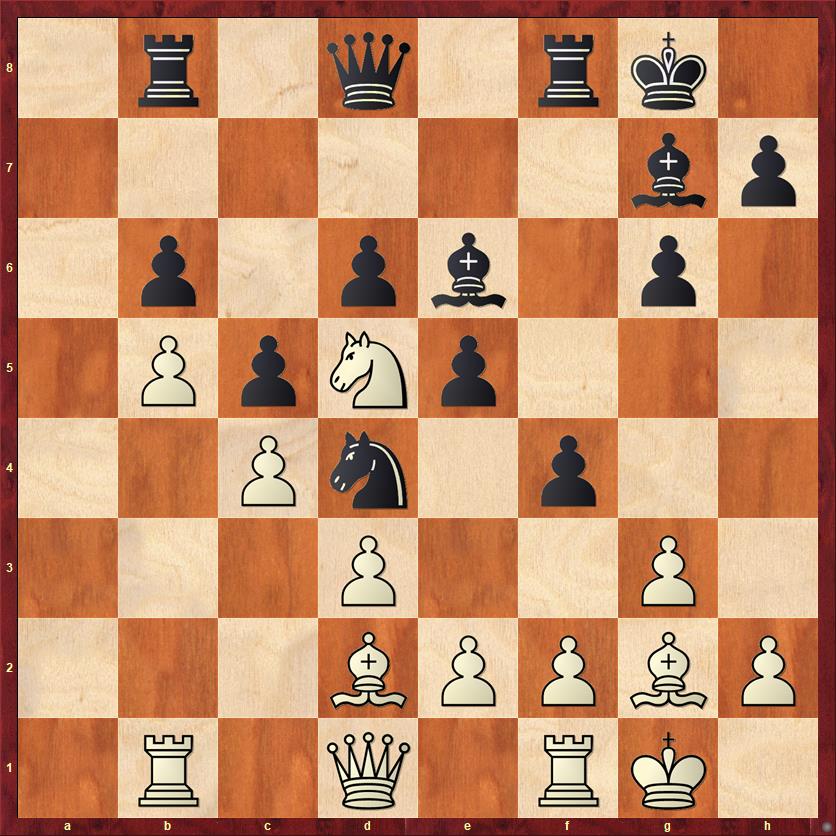

FEN: 1r1q1rk1/6bp/1p1pb1p1/1PpNp3/2Pn1p2/3P2P1/3BPPBP/1R1Q1RK1 b – – 0 18

Going over old games with the computer is so strange. My next move is the move I’m proudest of in this game… and according to the computer, it’s a mistake.

18. … f3!?

Instead, Fritz says I should have played 18. … Bg4! Because 19. Re1 f3 would be awful, White is forced to play 19. f3 and complete the entombment of his bishop. Black can now just play 19. … Be6 with a strategically much better position.

Even knowing this, I like the move 18. … f3 for play against a human opponent. It disrupts White’s pawn formation and forces him to make difficult decisions. In very short order, Black’s pieces start crawling all over the board. Speaking more generally, I think that my willingness to sac a pawn for positional pressure was an upgrade to my game that helped me make the leap from Expert to Master.

19. ef Bxd5 20. cd Qd7!

The move 20. … Qe8 would win back the b-pawn and restore material equality, but the queen is awkwardly placed and White can play 21. Re1 followed by f4 (twice, if need be!).

By comparison, 20. … Qd7 does not threaten to win back the pawn, because … Nxb5? would walk into a pin after Qa4. However, 20. … Qd7 does a lot of other good things. It connects my rooks and nails White’s rook to the b-file, which allows Black undisputed control over the a-file. I’m not playing to win back a pawn. I’m swinging for the fences.

21. f4?! …

Naturally, Kolvick wants to free his bishop. But this was probably his last chance to escape with an okay position by playing 21. Bc3. This takes advantage of the fact that the knight is not ready to take on b5. By taking the knight off the board, White can perhaps aim for a drawn opposite-color bishop endgame.

But I doubt that Kolvick wanted a draw. We’re both playing for a state championship!

21. … Ra8

Who would have thought a few moves ago that Black would gain control over the a-file? Note that the innocent reply 22. Ra1 now loses, because of 22. … Rxa1 23. Qxa1 ef, threatening to win the queen with a discovered attack and also threatening to win the king with 24. … f3 25. Bh1 Ne2 mate. Tactics like this are a sign that something has gone wrong for White.

22. fe Bxe5 23. Be4 Ra2

The position is easy to play for Black now. I am not the least bit interested in winning back the pawn with 23. … Nb5.

24. f4 Bg7 25. Rf2 …

White has to try to contest my rook on the seventh, but now the back rank is vulnerable. Although this is not a critical juncture yet, let me give you a diagram in case you’re trying to follow the game without a set.

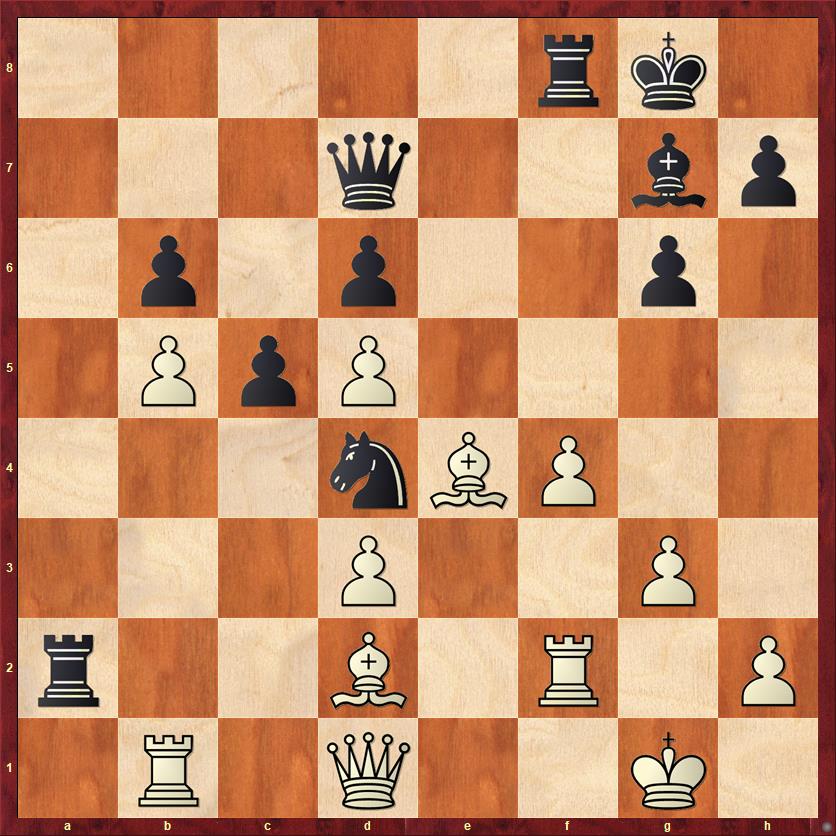

FEN: 5rk1/3q2bp/1p1p2p1/1PpP4/3nBP2/3P2P1/r2B1R1P/1R1Q2K1 b – – 0 25

25. … R8a8

Nothing fancy, but notice that 26. … Ra1! is already a serious threat. Once again, the discovered attacks on the long black diagonal are murderous. White’s next move is intended to stop … Ra1 by moving the king out of checking range by Black’s knight.

26. Kh1 …

Poor Randy, this position had to be hell to play.

26. … Nxb5

Now this move makes sense, again threatening … Ra1. The natural-looking answer 27. Qb3 now backfires horribly after 27. … Nc3! 28. Re1 b5!

27. Qf1 Ra1 28. Kg2 Bd4!

White cannot move the rook away, because 29. Re2 leads to mate after 29. … Rxb1 30. Qxb1 Ra1 31. Qb3 Rg1+ 32. Kf3 Qh3!

29. Re1 Rxe1 30. Bxe1 Bxf2

I kind of hate giving up this bishop for the rook; the move 30. … Ra1 seems more in the spirit of the attack. But the problem is, it might backfire after 31. f5. All in all, it seemed safer to eliminate the rook.

31. Qxf2 Nd4 32. Bc3 Qa4

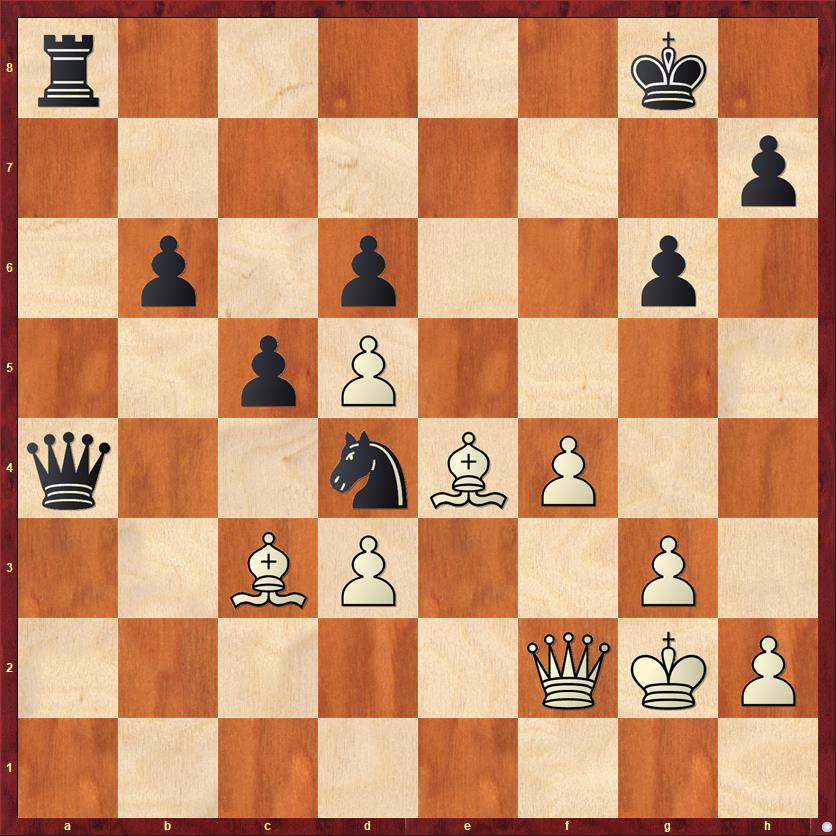

FEN: r5k1/7p/1p1p2p1/2pP4/q2nBP2/2BP2P1/5QKP/8 w – – 0 33

Now a really strange shift of psychology occurred. For the last 15 moves, ever since 18. … f3, the game has been so easy for me. It’s completely obvious that I’m winning now. In my mind, I was already 1987 North Carolina champion. There’s just one inconvenient detail: I still have to finish the game. But basically my attitude was, “Anything wins.” I stopped paying attention.

This is a terrible, terrible thing to do in any chess game, especially against a master. When I said this to Bernie Schmidt after the game, he told me, “Any time a master is still playing a position, you’ve got to take it seriously.”

For Randy, it was the opposite. The worst-case scenario has already happened. He’s had to live through ten moves of some of the worst agony I’ve seen on a chess board. Now the storm has blown over. He’s lost, but that also means he has nothing further to lose. He can try anything, and if it doesn’t work it doesn’t matter because he was lost anyway. Therefore:

33. f5 gf?!

Nothing wrong with this move, but two other good and less risky moves are 33. … Nxf5 or 33. … Qa2, offering a pawn to trade off the queens.

34. Bxd4 Qxd4?

Again I’m playing by rote and not considering the other options. Mike Splane always says that when you’re winning, your first priority is to extinguish all counterplay for your opponent. My move does the exact opposite, it creates counterplay for him. Much better was taking the other bishop with 34. … fe. After 35. Bb2 Rf8 36. Qe2 e3! I can start taking those victory laps. (But not 36. … ed?? 37. Qe6+ with a draw.)

35. Qxf5 Ra2+ Draw agreed.

Yes, you read that right. I proposed a draw in a completely winning position, and Kolvick accepted. I’ve got a lot of explaining to do.

First, the time situation: The time control was 50 moves in 2 hours. I’ve always hated 50-move time controls, because I don’t really recalibrate the speed of my play, and then I find myself in much worse time pressure.

So in this position, both Randy and I had only 3 minutes for 15 moves. This is some serious, nasty time pressure. I was already feeling the game slipping away from me, and I was scared that I would do something really stupid and lose it.

Apart from the time situation, there’s also the psychology of thinking you had the game won and all of a sudden realizing that it’s not so easy and you have to think again.

Finally, I feel pretty certain that I overlooked some important chess details. After 36. Kh3 Qg7 37. Qe6+ there is no indication in my notes that I saw the correct move, 37. … Qf7!, after which Black is still winning. The first point is that 38. Qxd6? Qh5 is mate, so obviously White doesn’t want to do that. But there are tons of other tricky tactics that both players need to wade through. First, after 37. Qe6+ Qf7! White can grab a free pawn with 38. Bxh7+. However, it backfires because after 38. … Kg7!, White either has to trade queens (with a dead-lost endgame) or lose the bishop.

Another possibility for White is to harass me with checks. For example, 38. Qg4+ Kh8 39. Qc8+ Kg7 40. Qg4+. If Black wants to win, he has to take his life in his hands and play either 40. … Kf6 or 40. … Kh6. According to the computer, they both work. But for a poor human with 3 minutes left on his clock, either of those lines is terrifying.

So, the upshot is that it was a complete crapshoot at this point. Literally anything could happen. I think that a draw was actually the most likely outcome. Instead of regretting the draw offer, what I really should regret is the careless play on moves 33 to 35 that got me into this mess.

Now, let’s come back to the tournament. I was absolutely crestfallen after this game. I was certain that I was going to lose the tiebreaks, because I thought for sure that Kolvick had played stronger opponents. He’s a higher-rated player, after all, right?

Well, in one of the two most stunning tiebreak outcomes of my chess career, it turned out that I beat Kolvick by something like a quarter of a point on the third tiebreak. So in fact, my draw offer on move 35 was the best draw offer of my career. It gave me a second state championship. But I absolutely did not know that at the time I made my offer.

So for me, this game is a very bittersweet memory. Thirty-two moves of chess nirvana, followed by three moves of unforgivably bad chess, followed by one of the luckiest breaks I’ve ever had.

For Randy, it was really rotten luck, but as I’ve already mentioned, he got his revenge with five more state titles. Actually, he didn’t even have to wait that long. Three months later, he won the North Carolina Invitational, a six-man round robin. We drew our individual game (again), and this time he was the one who probably should have won. I scored 2 1/2 – 2 1/2, which put me in third place. It is not clear to me why the North Carolina Open champion (or the top N.C. finisher in the Open) is considered the state champion and the Invitational champion is not; seems as if it should be the other way around. But maybe it’s precisely so that ordinary players like me can get lucky and win one. Or two.