By the end of 1982, it was starting to look as if my two-year sabbatical to focus on math instead of chess had been a good decision — not only for my math dissertation, but also for my chess game! My rating was up to 1989, the closest I had ever been to the “promised land” of 2000 and being an official chess expert.

My first tournament in 1983 was, again, the U.S. Amateur Team East championship. Again I was playing for the Princeton University team. We had a pretty good tournament, including a victory over the strong Collins Kids team (coached by Jack Collins, the legendary coach of Bobby Fischer). For me personally, it was an unforgettable tournament, as I went 5-0 on third board in the first five rounds. Unfortunately, one of my teammates had to miss round six and I had to move up to board two, where I got thumped. My dreams of winning a chess clock (for a 6-0 score) went up in smoke. Still, I had a pretty good consolation prize, my first expert rating. After six years in class A, it was about time!

However, the real reason I remember this tournament was none of the above things. Let me tell you about the day I played the world’s best chess computer … and won.

Princeton was paired against a team from Bell Labs, and the third board on that team was Belle, the world champion chess computer. Created by Ken Thompson, the same computer scientist who invented the programming language C, Belle had just become the first computer ever to achieve a USCF master rating (2200). I think that must have satisfied Thompson, because 1983 was the last year that he entered Belle in chess competitions. To him, I think, Belle was never anything more than a computer science experiment. He didn’t want to make any money off of it. When Belle reached a master rating, it was a successful end to the experiment. Thompson may also have seen that further progress in computer chess would depend more on brute force than programming advances. Until Alpha Zero, that is. But neither Thompson nor anyone else could have foreseen Alpha Zero 35 years earlier.

It may seem surprising to some readers that computers were even allowed in human competitions back in 1983. After all, we do our best to exclude them now, and computer-aided cheating is the bane of online chess. But this was a different era. Computers were allowed in most tournaments. (If not, there would be an “NC” for No Computers in the Chess Life announcement.) Usually individual players could choose not to play a computer, and the tournament director would do his best to honor their request.

Frankly, I considered those people to be chickens. When I saw that I was going to be playing against Belle, I was thrilled! When would I ever get such a chance again? (As it turns out, never.) I had never played against a computer before, not even a chess calculator. But I was young and afraid of nothing.

Obviously I’m showing you this game partly so that I can brag about beating the world champion chess computer. It’s something that not even Magnus Carlsen can put on his resume. But more importantly, I think it’s a historic game, a record of a unique moment when computers had just made the transition from a computer science experiment to a worthy adversary for even the best human players. You can see a few hints of the computer’s “science experiment” past in this game — particularly moves 30 and 43, where Belle played “too much like a computer.” There’s also one place, on move 19, where I definitely played “too much like a human.” My fallibility and Belle’s were just about perfectly balanced.

The latest chess engine I’ve used to analyze this game was Stockfish 10 at chess.com. It has an “accuracy” feature, which gives each player a grade from 0 to 100. I have to say that I was surprised — not by Belle’s grade (95.5, which is to be expected for a computer) but my grade, which was 98.9! According to Stockfish, I did not make a single mistake in the whole game: out of 50 moves, I played 6 book moves, 35 best moves, 4 excellent (but not best) moves, and 5 good (but not excellent) moves. I made zero inaccuracies (i.e., moves labeled ?!), zero mistakes (moves labeled ?), and zero blunders (moves labeled ??).

To be honest, I don’t agree. I did make an inaccuracy at move 19, and Stockfish spots it. (Belle didn’t.) According to Stockfish, my advantage before that move was +0.88 pawns, and if Belle had made the right reply my advantage would have gone down to +0.28. So my “perfect game” was not quite perfect.

However, Stockfish’s analysis did give me a new way of looking at this game after all these years. I’ve always looked at the game from the point of view of “what did the computer do that was stupid?” But I didn’t give myself enough credit for doing the right things. I won simply by being more accurate than Belle, and that was a pretty good accomplishment for a class A player.

Okay, enough chatter. Let’s get to the game!

Dana Mackenzie — Belle Computer

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 c6 4. e4 de 5. Nxe4 Bb4+ 6. Nc3 …

I had never seen this variation before. The sharpest answer for White is 6. Bd2, sacrificing a pawn after 6. … Qxd4 7. Bxb4 Qxe4+ in order to win the two bishops and trap Black’s king in the center. I don’t think that I seriously considered this. Even if I had known the theory — which I didn’t — it would be a questionable decision to go into a highly tactical line against a computer that is guaranteed to know all the theory.

And besides, 6. Nc3 is a perfectly good move! Not ambitious, but not bad either.

6. … Nf6 7. Nf3 O-O 8. Bd3 c5 9. O-O cd 10. Nxd4! …

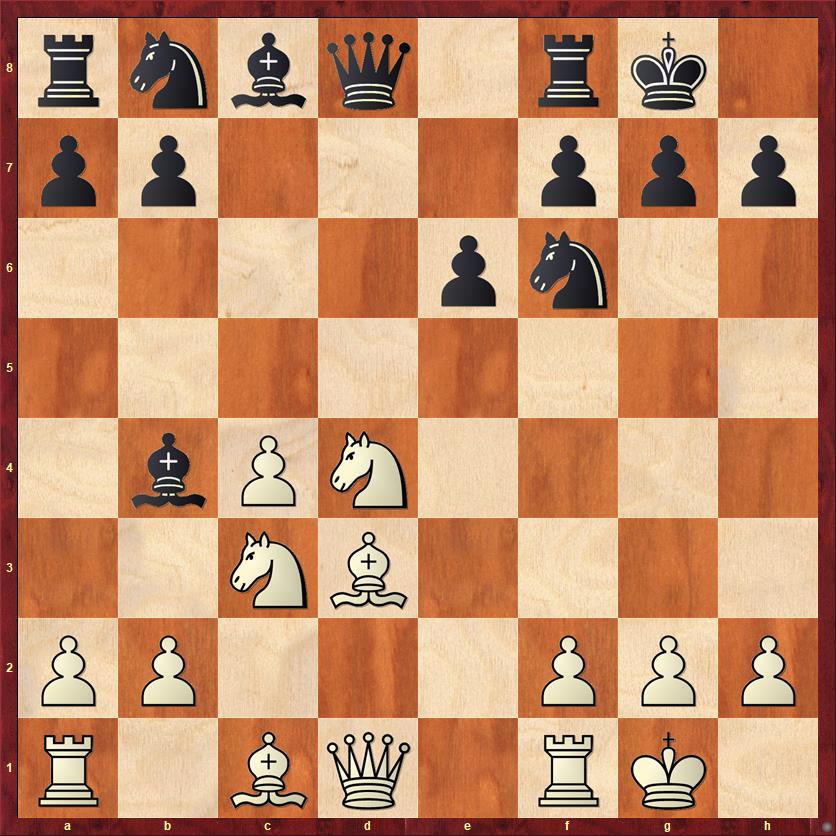

Time for our first diagram.

FEN: rnbq1rk1/pp3ppp/4pn2/8/1bPN4/2NB4/PP3PPP/R1BQ1RK1 b – – 0 10

I like this move! Of course, we all see the trap 10. … Qxd4?? 11. Bxh7+ winning the queen. But the more important thinking behind this move is strategic. White could have played 10. Ne2 or 10. Nb5, winning back the pawn without allowing Black to take on c3 and double the c-pawns.

But I played 10. Nxd4, inviting Black to double my c-pawns. At this point in my career I had a theory that doubled pawns are not as bad as is commonly believed. The reason is that they usually entail an increase in open lines for the pieces. In this position, White gets an open b-file and a nice diagonal from a3 to f8, and both of those things will turn out to be important factors in the next few moves.

So my move has to be seen as a “positional gambit,” sacrificing one positional factor (pawn structure) to gain other positional advantages (open lines, two bishops, active pieces). I was counting on the fact that Belle, having been programmed by a human, might have the same prejudices a lot of humans do. I don’t know whether this theory was correct or not, but Belle did take the bait.

10. … Bxc3?!

At this point Belle evaluated the position at 0.17 pawns in Black’s favor, its most favorable self-evaluation of the game. A more modern computer program like Fritz 17 prefers White, by 0.53 pawns. And Stockfish splits the difference, coming in at +0.20 pawns for White.

11. bc e5 12. Nb5 e4

Belle continues to play very aggressively and sharply.

13. Bc2 Qa5

Belle wants to free d8 for its rook. But the queen is not exactly comfortable on a5, and White’s next move poses additional problems. Black’s position just feels overextended and underdeveloped.

14. Bf4 Nc6 15. Nc7! …

This move is again more sophisticated than it appears. It looks as if I’m just trying to grab the exchange. However, Black can easily get out of that threat by playing the in-between move 15. … Bg4. The sneaky thing about 15. Nc7 is that the knight creates some havoc in Black’s position just by being there. It keeps a rook from coming to e8, it cuts the queen off from the rest of her army, and it has designs on coming to d5 later.

15. … Bg4 16. Qb1 …

What a great spot, at the intersection of two important lines, the b-file and the b1-h7 diagonal.

16. … Rad8 17. Qxb7! …

I like the fearlessness of this move, especially because I distinctly remember feeling at this point in the game that the position was spiraling out of my control. I did not know whether this move was smart or stupid, but I didn’t see anything wrong with it, so I played it. Fritz and Stockfish both say it was smart.

17. … Qxc3 18. Qxc6 Qxc2 19. Bd6?! …

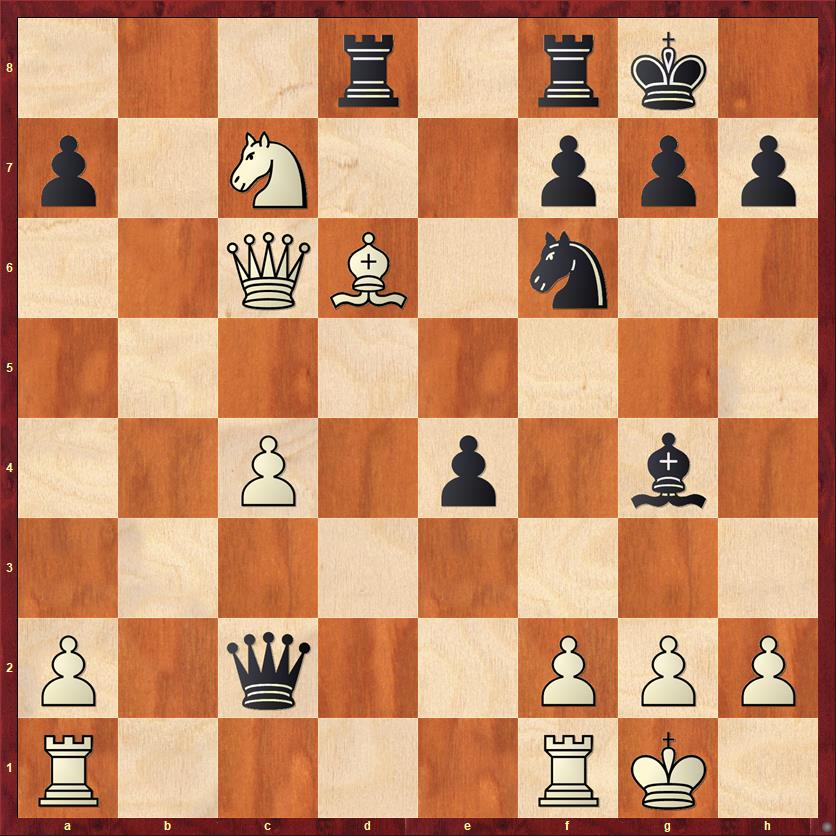

FEN: 3r1rk1/p1N2ppp/2QB1n2/8/2P1p1b1/8/P1q2PPP/R4RK1 b – – 0 19

Here it is, my one inaccuracy of the game. This is a move that I believe 99 percent of humans (at least beyond a certain minimal skill level) would choose. It just seems like a straightforward win of the exchange. Yet according to Stockfish, 19. Be5 was better. I think it would take GM-level insight to pass up the win of an exchange and play that move instead.

The above position is a great litmus test, for both computers and humans. Can you figure out what Black’s resource is in this position? If you can’t, don’t worry. I didn’t see it. Belle didn’t see it. Even more remarkably, Fritz 9 (circa 2005) didn’t see it. Rybka 3 (circa 2008) was the first chess program I owned that found the right move for Black here. Fritz 17 and Stockfish 10 (circa 2020) laugh and say that it’s obvious.

Belle played

19. … Rxd6?

acquiescing to the loss of an exchange. My one criticism of it is that Black gets to a position that is lacking in counterplay. In fact Black is close to lost after this move. In such a situation, almost anything else, no matter how desperate, is worth considering. And such a move is 19. … Be2! Of course White will play 20. Rfc1, gaining a tempo with an attack on the queen and defending the c-pawn. Black plays 20. … Qd2, and now White grabs the exchange with 21. Bxf8. And here Black has the amazing resource 21. … e3!!

How’s that? Can’t White just play 22. Bc5 and end up a full rook ahead? No! On 22. Bc5 Black wins with the stunning move 22. … Bd1!! when Black now threatens … Qe1 mate as well as … Qxf2+ and the pawn push … e2. White has to nip this threat in the bud, so he’ll likely play 22. fe Qxe3+ 23. Kh1 instead. But now after 23. … Ng4! 24. Bc5! (covering the g1 square so that Black can’t play the “Philidor’s Legacy” combination) 24. … Nf7+ 25. Kg1 Nh3+, it’s a simple draw by repetition.

No wonder I didn’t see this amazing resource. I was thinking too much like a human, going for the simple win of material. It’s a little more surprising that a good commercial program like Fritz 9 still didn’t see it as recently as 2005.

20. Qxd6 Qxd4 21. Rfc1 Qa4 22. Nd5 Nxd5 23. Qxd5 Be6 24. Qe5 Rd8?!

A week or two after the game was played, Ken Thompson sent me a scoresheet not only with all of the moves but also a printout of Belle’s top choice at each number of ply. This move was a particularly fascinating case because Belle changed its mind twice. At a depth of 3, 4, and 5 ply it preferred 24. … Rd8. At a depth of 6 and 7 ply it preferred 24. … Re8. And at a depth of 8 ply it changed back to 24. … Rd8. But 24. … Re8 was clearly a more feisty move, pointing out that e5 might not have been the best square for my queen. After the text move, Black’s position just becomes very passive.

25. Re1 Bd5 26. Red1 f6 27. Qc7 Rd7 28. Qc8+ Kf7 29. h3 …

Probably better was 29. Rac8, but I’m basically saying that I am in no hurry and I’d like to make luft for my king so that I won’t fall into any back-rank mates.

29. … Be6 30. Rxd7+ …

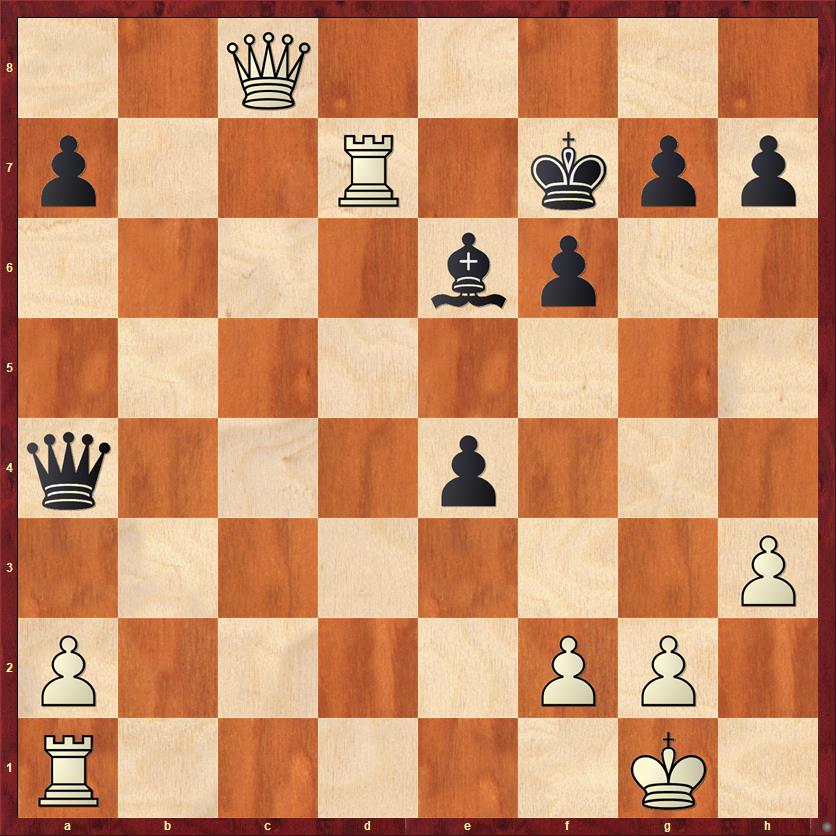

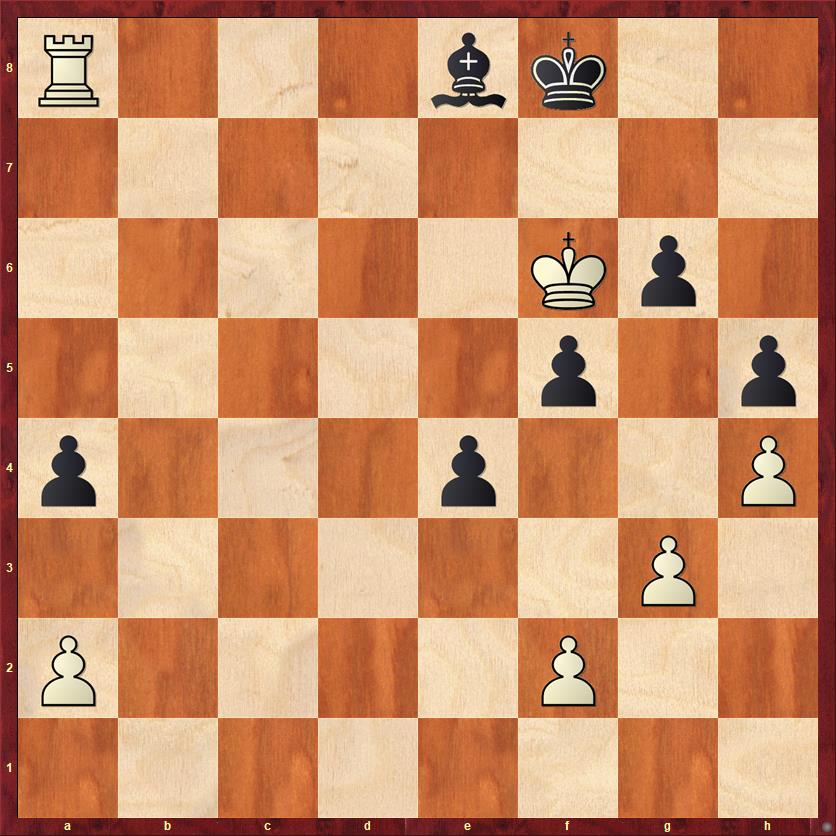

Time for another diagram. This is a very interesting position, not for humans (because White is clearly much better) but for probing the difference between humans and computers.

FEN: 2Q5/p2R1kpp/4bp2/8/q3p3/7P/P4PP1/R5K1 b – – 0 30

Which way should Black recapture? I think that most humans would say, without much thought, that 30. … Bxd7 is better. Black is clearly fighting for a draw, and his only hope is to keep the position complicated and keep queens on the board.

But every generation of computers, from Belle to Fritz 9 to Rybka 3 to Fritz 17 to Stockfish 10, has concluded that 30. … Qxd7 is better. Maybe not by much, but at least by a little bit. I think the reason is that the computer sees that White’s queen and rook together can create so many dangerous threats that Black cannot hold out for very long. With queens off the board, on the other hand, White cannot win with a direct attack but must squeeze a win out of a prolonged endgame.

Therefore, Belle played

30. … Qxd7?!

a move that I consider to be “too much like a computer.” When Belle played this move during the game, I was for the first time absolutely sure that I was winning. It turns out to be a little more complicated than I thought, but still I was right. White should win this position. Belle, on the other hand, felt that after the queen trade its deficit had shrunk from 0.8 pawns to 0.5 pawns. In other words, it is going by the classical rule that a bishop and pawn against a rook is a “half-pawn” deficit. This shows the downside of evaluating positions based on a pawn count equivalent, as every computer until AlphaZero did.

I suspect that AlphaZero, which evaluates positions based on winning probability, might be the first computer to “think like a human” and prefer 30. … Bxd7. If anyone wants to try this out with one of AlphaZero’s imitators, I’d be interested to see what it says.

31. Qxd7+ Bxd7 32. Rb1 a5 33. Rb7 Ke6 34. Ra7 a4 35. Kf1 f5 36. Ke2 …

FEN: 8/R2b2pp/4k3/5p2/p3p3/7P/P3KPP1/8 b – – 0 36

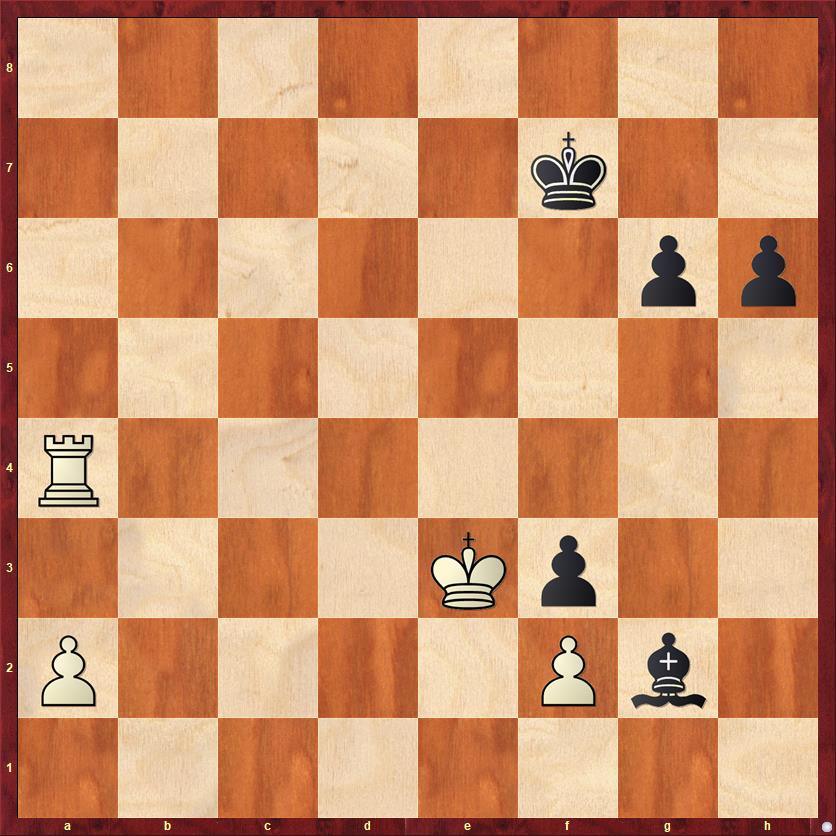

Okay, let’s talk about this endgame. Although I’m obviously “ahead in material,” that doesn’t necessarily mean I’m winning. And even if I’m winning, I need a plan — the game won’t win itself.

Actually this position is quite interesting because it’s a decision point for Black. One strategy for him is to play pure defense, put all of his pawns on White squares, keep everything defended and ask White how he’s going to make progress. It’s important to realize that the most obvious plan for White does not work. White cannot just bring his king to the queenside and sac his rook for the a-pawn and bishop, creating an outside passed pawn. The reason is that Black’s pawns on the kingside are too fast, and he will queen first.

Instead, if Black puts all his pawns on the light squares, White will infiltrate on the kingside, using tempo moves to force Black’s king back. White is aiming to (eventually) reach a position like this one:

FEN: R3bk2/8/5Kp1/5p1p/p3p2P/6P1/P4P2/8 b – – 0 50

This is the apotheosis of Black’s strategy of keeping everything defended. But his problem is that he’s in zugzwang — he has to move and that move will cost him material. (Even if he wasn’t in zugzwang, White can now win by sacrificing his rook for the bishop and taking on g6.)

Going back to the previous diagram, Black’s other strategy is to play … f4, delaying White’s king invasion for as long as possible and getting ready to mobilize his other pawns. But the downside of … f4 is that the e-pawn is weakened, and Black will get to the point of having too many weak pawns to defend. He can defend two but he can’t defend three.

Nevertheless, this is clearly Black’s best hope. The farther advanced the pawns are, the more careful White needs to be.

36. … f4!

Hey, I might as well give Belle credit for doing one thing right this game!

37. Kd2 g6?!

This move, on the other hand, makes no sense. See my comment above. 37. … g5 saves a tempo. White would still be winning, but the margin of victory is narrower. For fans of long-winded computer analysis, here is how the game might go (analysis courtesy of Fritz):

37. … g5 38. Kc3 h5 39. Kd4 h4! is Fritz’s clever idea. This prevents White from playing h4, and puts White on the spot: can he afford to take on e4 and lose both the g2 and h3 pawns? Actually 40. Kxe4 is playable, but a much safer and simpler move is 40. Rc7! preventing Black’s bishop from coming to c6. Black has to play 40. … Kd6, but now his king has strayed too far from the g-pawn. White can play 41. Rc5 winning a pawn and the game.

38. Kc3 f3!

Setting a trap: after 39. g3?? e3! would win for Black! Yikes! Of course I didn’t fall for that.

39. gf ef 40. Kd4 h6 41. Ra6+ Kf7

This retreating move might seem a little bit odd, but Belle was enticed by the possibility of winning my h-pawn. If 41. … Kf5 42. Ke3 Kg5 43. Kxf3 the f-pawn is dead and Black doesn’t even get the h-pawn.

42. Ke3 …

The king completes its long, strange, circuitous march from the kingside to the queenside and back to the kingside again. The f-pawn cannot be defended, but Belle is under the illusion that it can.

42. … Bxh3 43. Rxa4 Bg2?

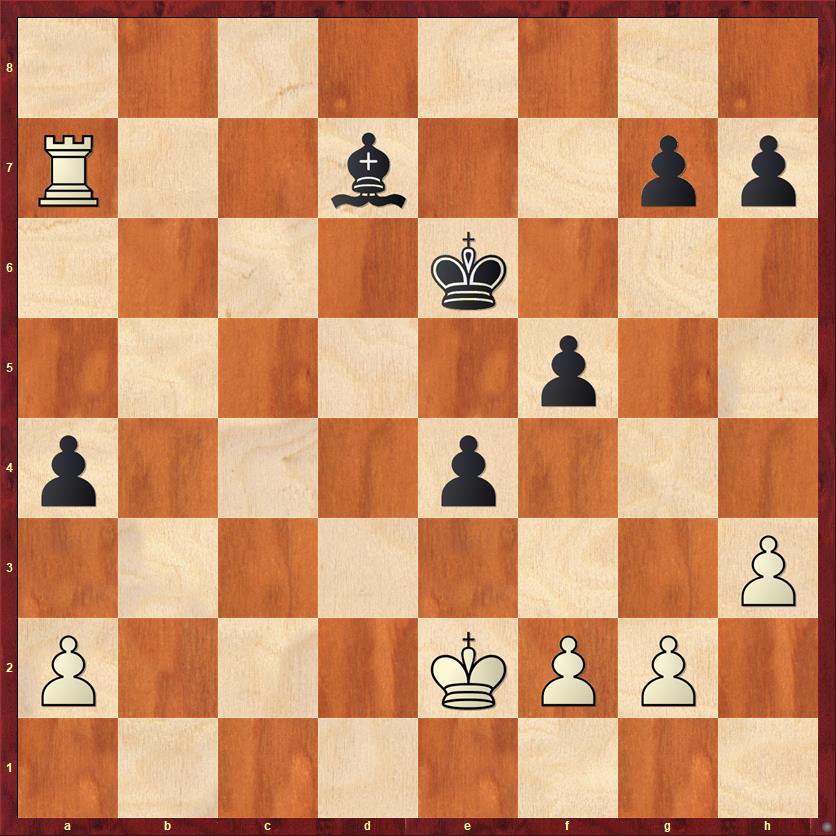

FEN: 8/5k2/6pp/8/R7/4Kp2/P4Pb1/8 w – – 0 44

The last interesting position of the game, more for historical reasons than for chess reasons. One problem for computer chess programmers has always been the “horizon effect.” No matter where you place your “horizon” for analysis, the computer is going to be blind to things that happen beyond the horizon. Here, Belle sees that it is defending the f-pawn and even has threats of pushing and promoting its own h-pawn. It in fact believes that White has made a major blunder; after bottoming out at -2.53 pawns a couple moves ago, it now thinks that it is only behind by -0.75 pawns.

By contrast, a human can see what a computer of that era could not: the bishop on g2 can never stop my a-pawn. And because my rook can easily keep Black’s king from reaching the a-file, Black has no way to keep me from promoting. It will eventually have to move its bishop from g2, and at that point I can take on f3 and its decision to protect the pawn on f3 will have been worse than useless.

This kind of “eventually Black will have to…” logic entails pushing the horizon arbitrarily far back, and it’s the sort of schematic thinking that is still hard for computers even today. I believe that programmers have made some work-arounds, because you don’t see Fritz making mistakes quite this bad, but I don’t think they have solved the problem completely. Except maybe for AlphaZero.

All that White needs to do now is play Rd4 to cut off Black’s king, Rd1 to defend against the h-pawn promotion, and then start running the a-pawn. The rest of the game needs no comment.

44. Rd4 h5 45. a4 Ke6 46. Rd1 Ke5 47. a5 Bh3 48. a6 Bc8 49. a7 Bb7 50. Rd8 and Black resigned.

Belle didn’t have a feature to decide on its own when to resign; instead, Ken Thompson (who entered all the moves) had to decide for it. He certainly knew enough about chess to see that White is going to play a8 and win Black’s bishop. However, I’m not sure if I would have resigned the position just yet! The reason is that after 50. … Kf5 51. a8Q Bxa8 52. Rxa8 Kg4, White still has to decide how he is going to win. If Black could somehow get to a position with K+RP versus K+R, then he would be able to draw. If I were Black, I would at least play long enough to see that my opponent has a plan for avoiding that endgame. A good forcing line for White is 53. Ra4+ Kh3 54. Kxf3 g5 55. Ra5 g4+ 56. Ke3 h4 57. Rg5. If 57. … g3 58. fg hg 59. Kf3 winning the last pawn. [Note: I left out a couple moves in original post, corrected about two hours later. Sorry about the confusion.]

This was a long game, without any flashy attacks, but I think it is much better on a conceptual level than most of my games from this period. And my win over a world champion is something that can never be taken from me!

Lessons:

- Explore the idea of sacrificing one positional imbalance for another. Here, sacrificing pawn structure for piece activity and open lines.

- Doubled pawns are often underrated. Many people assume they are automatically bad. But it all depends!

- Desperate times call for desperate measures! Although personal taste enters into the decision, I would usually prefer to play a move like 19. … Be2 that at least throws a scare into my opponent, instead of a move like 19. … Rxd6 that locks Black into a passive, inferior position.

- Don’t be a slave to material count. Machines have improved a lot by incorporating other factors into their evaluation, and so can you. Also, especially in the ending, a material advantage means nothing if you don’t have a plan to use it.

- Zugzwang is often the secret ingredient that breaks down a passive defense in the endgame.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Nice game and an interesting account!

I remember playing two tournament games against computers back in the day, probably around roughly the same time frame as your Belle encounter. Both games were against computers that were in the process of coming to market. One was the Novag, and I forget the other. Both were rated somewhere in the 2000s at our time limit (approx G/90 or so).

I forget the details of the drawn game, but I beat the other computer due to a better positional understanding. I was able to reach a position where I had a good knight against my opponent’s bad bishop. In fact, White willingly blocked in its QB with f4 in the late opening, and paid for it later on.