When you put a call out to the universe, sometimes the universe answers! A couple weeks ago I mentioned that I did not have the scores of any of my games from 1976. But then I got an e-mail from an old friend I hadn’t heard from for many years: Macon Shibut, who was a frequent sparring partner of mine at the Second Sunday Quads and the chess club at the Virginia Home.

Macon sent me a game score that he thought was from 1976, because he remembered still being in high school at the time it was played. However, I found a diary entry from June 11, 1978 that describes the game to a tee. Macon concedes, “a written diary trumps liveware recollections.” So I couldn’t put this game into a 1976 post. But it’s a very entertaining game, and very suitable for my 1978 entry. I’m grateful to Macon for unearthing it!

The best thing is that I can add Macon’s comments to my own, so you’ll have both points of view on this exciting game.

Dana Mackenzie — Macon Shibut, 6/11/1978

1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4 cd 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 e5 6. Ndb5 d6 7. Bg5 …

In those days the Sveshnikov variation was really popular, and I faced it a lot. In fact, my distaste for playing against it is one reason I eventually stopped playing the Open Sicilian (though not the only reason). Here White has a couple other options: 7. a4 or 7. Nd5. I think, though, that 7. Bg5 has always been seen as the most principled test. White would like to pin Black’s f6 knight and only then sink his own knight on d5, to take advantage of the hole created by Black’s fifth move.

7. … a6 8. Na3 b5 9. Nd5 Qa5+ 10. Bd2 Qd8 11. Bg5 …

Macon was probably higher-rated than me at the time, and so I was okay with a draw. Of course, he was not okay with that (and most Sveshnikov players wouldn’t be — they play this opening because they want a battle). So from the practical point of view, he has to look for a different option than … Qa5+.

11. … Be6 12. c3 Be7 13. Bxf6 Bxf6

The other option is 13. … gf, which may actually be better.

14. Nc2 Bg5 15. a4 ba 16. Rxa4 …

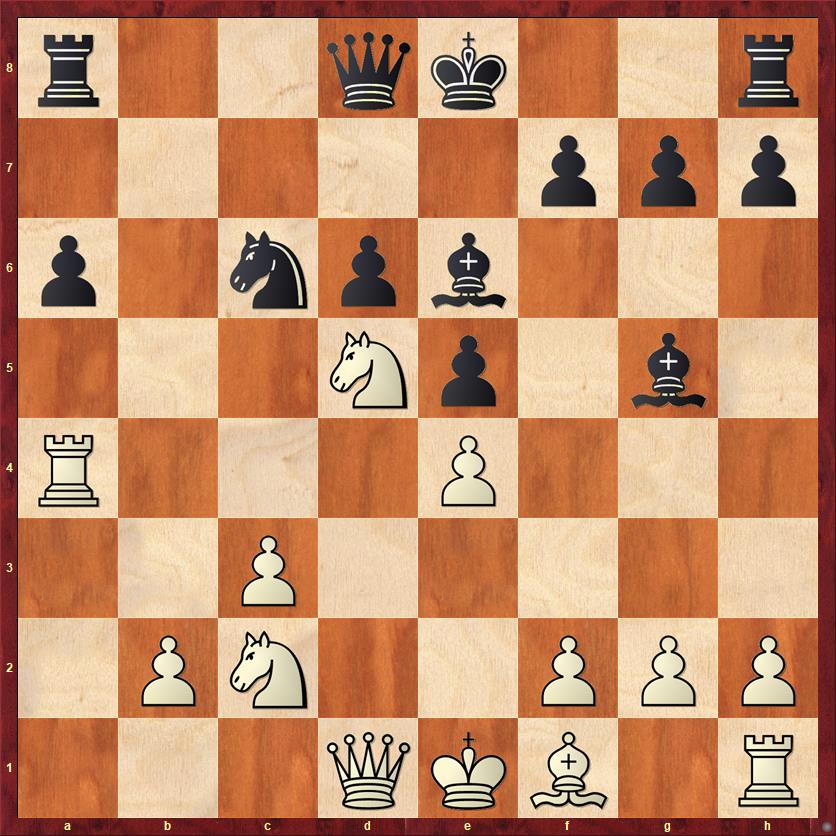

Time for our first diagram, and our first comment from Macon.

FEN: r2qk2r/5ppp/p1npb3/3Np1b1/R3P3/2P5/1PN2PPP/3QKB1R b Kkq – 0 16

Macon: A billion games have gone 16. … a5. Then as now, I believed in piece activity and “natural” moves as the most important thing in chess, even more than material, but of course I have been force to rein in my extremist instincts on this over the years. In any case, I’m certain that (1) I didn’t know the “theory” when this game was played; and (2) I did notice that a6 was hanging and sacrificed it intentionally. Sacrifice by ignoring/not bothering to defend against direct threats was one of my favorite themes.

Dana: This comment shows why Macon was always a tough challenge for me to play against! Because I have the same philosophy. The one thing that surprises me about this comment is that 16. … a5 would be the “theory” here. Both in computer analysis and in practice it has done poorly against 17. Bb5! with the idea of 17. … Bd7 (or … Rc8) 18. Rc4! This rook-super-lift has not been played very much in human games, but the computer gives a really substantial advantage to White, like 1.8 pawns. One example in human chess is the game Joaquin Diaz – Manuel Flores, Mexico City 1991, which went 18. … Rc8 19. h4 Be7 20. Nce3 g6 21. Qa4 Nb8. White just traded pieces and won a pawn after 22. Rxc8 Qxc8 23. Nxe7 Kxe7 24. Nd5+ Kf8 25. h5 h6 26. hg fg 27. Qxa5 etc. No player in their right minds would want to play this as Black. So what gives with the “theory”?

By contrast, the machine likes Macon’s pawn sacrifice much better. It doesn’t think Black has full compensation, but for a game between humans it’s definitely playable. Let’s forget about the computer. For his pawn Macon has lots of piece play, which is what he was all about and what the Sveshnikov variation is all about.

16. … O-O! 17. Rxa6 Rxa6 18. Bxa6 Qa5 19. Bc4 Qc5 20. Na3?! …

When Black sees a move like this, he feels he has already won a small victory. White wastes a tempo to move a piece to square where it just came from… and moreover it’s a “knight on the rim.” That being said, the move tactically seems to work for White. In 1978 I thought much more in terms of tactics than strategy. Today I would probably play 20. Qe2.

20. … Ra8 21. b4! …

Development be damned. Weaknesses be damned.

21. … Nxb4!?

Macon: Ditto all the comments at move 16 — in for a penny, in for a pound.

Dana: The only other move for Black is 21. … Qa7, but after 22. Nb5 it looks to me as if White has the active pieces, not Black! You could say my 20th and 21st moves were brilliant, baiting Black into an unsound piece sacrifice. But in truth, in my previous years as a class-B, C, and D player, I had never met an opponent like Macon before, who would be so willing to sac a piece for the sake of principle. I strongly suspect I was stunned by his 21st move.

22. cb Qc6 23. Bb5 Qc8 24. Nc2! …

The knight keeps changing its mind: a3 or c2? It turns out that c2 is a great square because it protects a1 and frees White’s queen to enter the game. White definitely does not want to play 24. Nc4? because 24. … Bxd5 25. ed Qb8 would win back the piece.

24. … Bxd5 25. Qxd5! …

I too believe in active pieces… and back-rank checkmates.

25. … Qc3+ 26. Kf1 Rc8 27. Bd3?! …

Though it’s not a bad mistake, I think this is my first misstep. The move 27. Ba4!, suggested by the computer, is a “sneaky good” move because Black is simply out of ways to improve his position. The only move to make progress is 27. … Qb2, but after 28. g3 White simply walks his king out of trouble. Black’s pieces, though active, don’t seem to be cooperating with one another.

By contrast, after 27. Bd3 Black has a very easy and obvious way to make progress. I think that this move shows a weakness of mine at the time (and maybe still) — I wasn’t a very strong defender, perhaps because I didn’t think enough about the question: What does my opponent want to do?

27. … Qd2

The game is kind of reminiscent of my game against Kevin Toon a few entries ago. White allows an alien piece into the very guts of his position. When you do that, you’re asking for trouble. White is still much better, in the objective computer evaluation, but his position is internally sick.

28. g3 h5 29. h4?! …

Man, continuing to flirt with disaster. I’m not sure whether I didn’t see the danger or whether I just didn’t know what to do about it. More circumspect would be 29. Kg2, getting the king to safety. After that, the computer analyzes 29. … Rc3 30. Ne1 Be3 31. Rf1, and we get another “maxed out” position for Black, where he just lacks the material to put any more pressure on White. Meanwhile, White is preparing to play Bc4 and seize the initiative back.

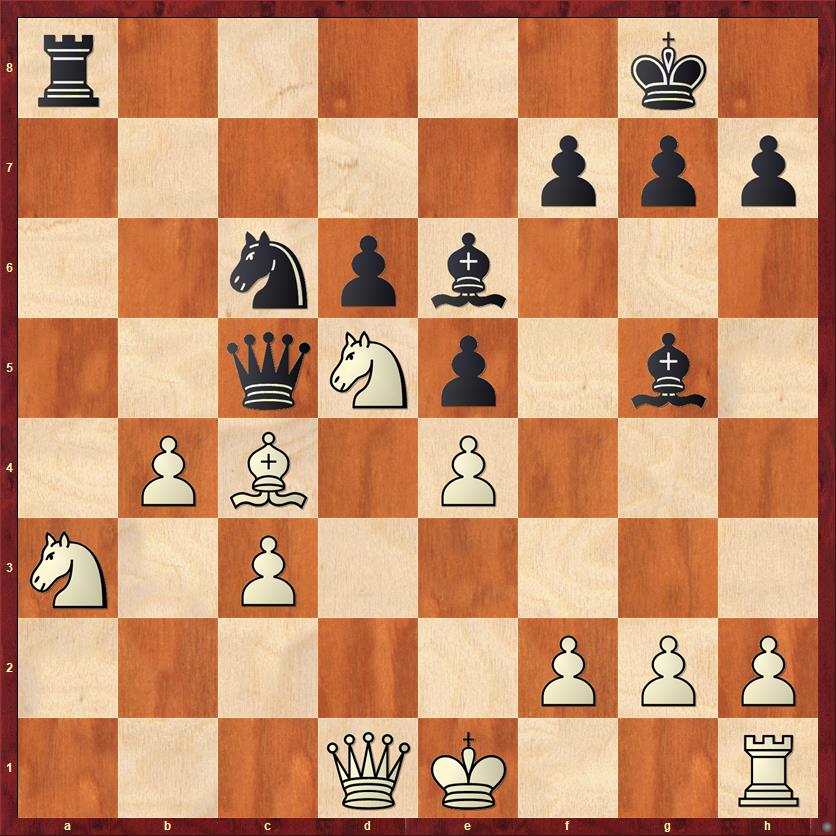

FEN: 2r3k1/5pp1/3p4/3Qp1bp/1P2P2P/3B2P1/2Nq1P2/5K1R b – – 0 29

29. … Rc3!

Once again we see Macon’s strategy of ignoring direct threats, in this case the threat on his bishop. In a sense this is not a sacrifice, because he gets my bishop in return — but in a sense it is a sacrifice because he is letting me achieve my dream of a back-rank check, and even more.

Of course it should not work. But one lesson to learn from this game is that things that should not work often do.

At the risk of repeating myself, I was completely unprepared for an opponent who could repeatedly play this kind of move.

30. hg Rxd3 31. Qa8+ Kh7 32. Rxh5+ Kg6

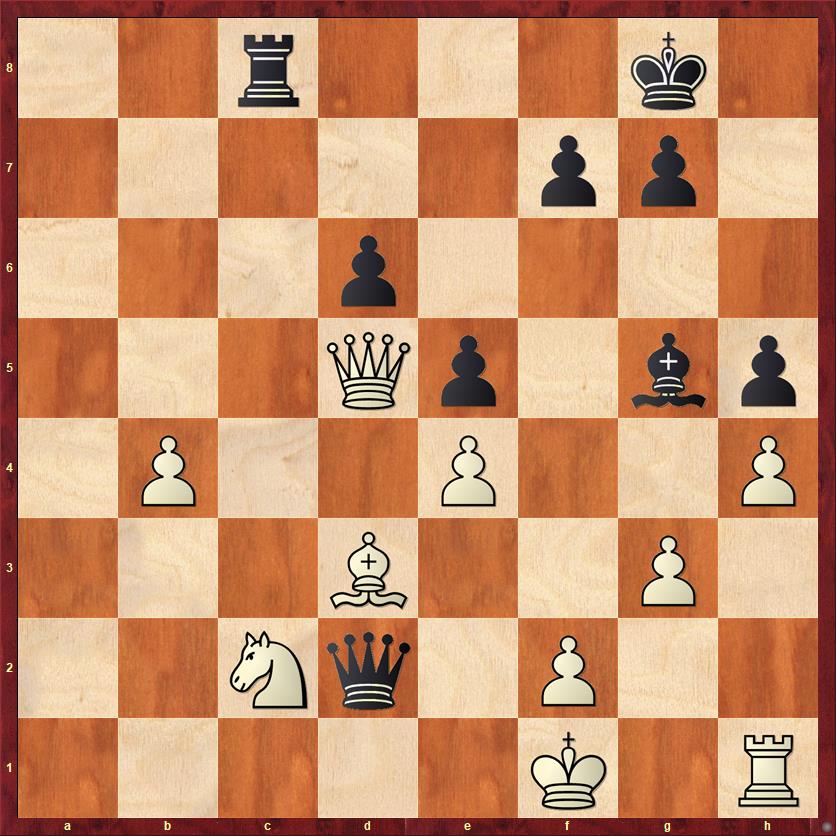

The critical moment of the game. How does White deal with the simultaneous threats on his knight and rook?

FEN: 2r3k1/5pp1/3p4/3Qp1bp/1P2P2P/3B2P1/2Nq1P2/5K1R b – – 0 29

Macon: You could have tried 33. Rh6+ and if 33. … gh? 34. Qg8+ Kh5 35. Qxf7+ Kxg5 36. Qf5 mate. We found this in the postmortem. But 33. … Kxg5! spoils it.

Fritz (computer): In fact, 33. … Kxg5! doesn’t spoil it, as long as White finds the remarkable resource 34. Qh8!!

Dana, 2020: However, this move begs the question of why White didn’t play it a move earlier. In fact, 33. Qh8! is clearly the winning move. White threatens checkmate, and Black has only one way to stop it: 33. … Qd1+ 34. Ne1! Qxh5 35. Qxh5 Kxh5 and, alas for Black, his rook is hanging: 36. Nxd3 and White wins easily.

This is really beautiful and somewhat hard to see; you have to realize that the seemingly innocuous defensive move 34. Ne1 actually contains a threat (Nxd3). On the other hand, that doesn’t excuse my not seeing it. It seems absolutely clear to me today that 33. Qh8 should have been the first candidate move to look at. Threatening checkmate is stronger than threatening check, or giving a check. From there to 36. Nxd3 is basically a forced sequence.

So why didn’t I see this move? Let’s ask my diary.

Dana, 1978: I could have refuted [Macon’s] sacrifice with a lovely counter-sacrifice of a rook that, rattled by time pressure, I discarded as too complicated to analyze.

Dana, 2020: This tells you everything you need to know. I was in time pressure, of course. Throughout my career I have been prone to time pressure, and this game was a particularly complex game. I was clearly lusting to play the rook sacrifice, 33. Rh6+. In part this is because of the mistaken ethos I’ve written about before, that winning with a sacrifice is somehow more glorious or better than winning with simple chess. So I’m sure I burned most of my remaining time trying to find a win after 33. Rh6+, couldn’t do it, panicked and played

33. Qc8?? …

For all practical purposes, conceding a draw. But by now I was in full-blown meltdown/panic mode, as we’re going to see.

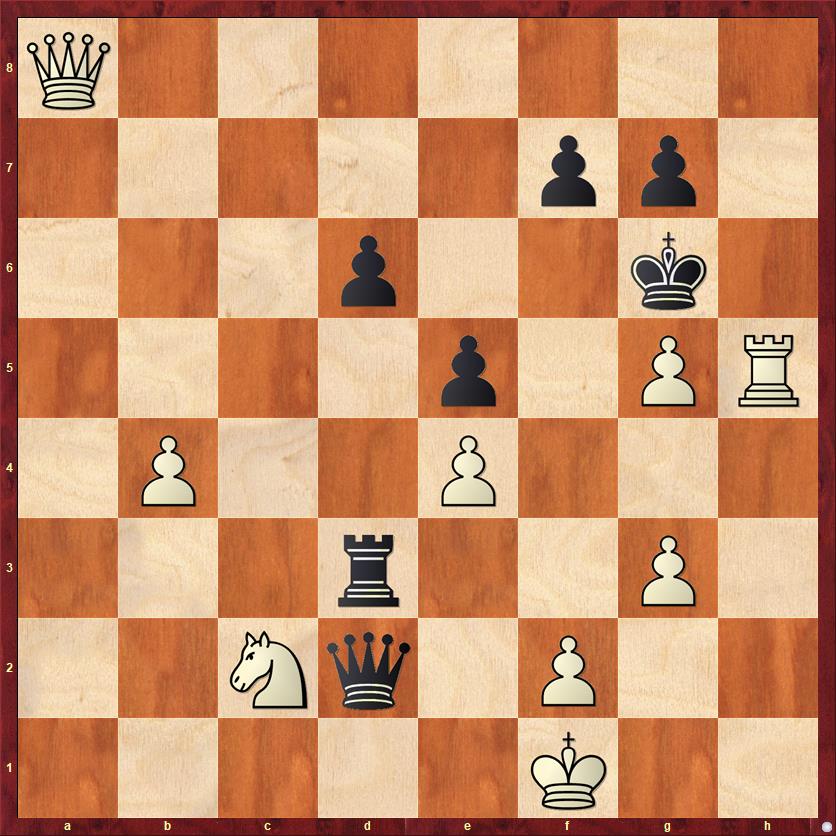

33. … Qd1+(?)

A mistake only a computer could spot. Technically, 33. … Kxh5 right away was better.

34. Ne1 Kxh5 35. Qh3+(?) …

Fritz says that White is winning again after 35. Qf5!! (+2 pawns for White), but would not have been winning if Black had taken on h5 right away on move 33. For humans, and especially humans in time trouble, these subtleties are completely incomprehensible. But this is another case where a move that takes away flight squares from the king is better than a check.

35. … Kxg5

And now the complete meltdown occurs:

36. f4+?? …

This is what I call “hope chess.” I’ll just keep flailing away at his king and hope that something turns up. Here I should have immediately played 36. Qf5+ and thanked my lucky stars that I still have a draw by repetition. After 36. … Kh6 37. Qh3+ he has to go back to g5 or g6, because 37. … Qh5?? would lead to the same lost endgame we saw before.

I just didn’t want to admit I had screwed up and bail out to a draw. Instead I bailed out to a loss. This was immaturity. Older Dana has bailed out to a draw enough times that I no longer feel any shame in doing so.

36. … Kf6 37. Qf5+ Ke7 38. Qg5+ Ke8 39. Kf2 Rd2+ 40. Ke3 Qe2 mate

Oh well, at least I made it to the time control.

In spite of the disastrous finish, I think this was a very entertaining game and a lot of credit is due to Macon, who never gave up, kept applying pressure and was rewarded for it in the end.

There are so many great lessons in this game that it’s hard to narrow them down to just seven, but here they are.

Lessons:

- Winning with a “brilliant sacrifice” is not better than winning with simple chess. Losing because you spent too much time analyzing a “brilliant sacrifice” is worse than winning with simple chess.

- When your opponent threatens a piece, besides the usual options of moving it or defending it, you should always ask if there is a third option: ignoring the threat. That is the strategy that Macon used to perfection in this game.

- Believe in active pieces… and back-rank mates.

- A threat of checkmate is usually stronger than a check. This especially applies to “king hunt” types of positions.

- A key to successful defense is asking yourself what your opponent wants to do.

- “Hope chess” seldom works. Hope chess, where you play moves in the hope that your opponent will make a mistake or that some threat will turn up that you don’t see yet, is different from a speculative sacrifice, where you give up material for concrete counterplay and known threats, which can’t be calculated to the end.

- Screw-ups happen. There is no shame in bailing out to a draw in a game where you once had a winning advantage. The road to mastery is just as much about not losing as it is about winning.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I love these old games, and the stories that go with them. Thanks for sharing the game!

Good column, thanks!