Recently it occurred to me that I’m getting very close to the 50th anniversary of my debut in tournament chess. There aren’t so many people who stay active in chess that long. Why not start a series of posts where I pick one game from each year to annotate? I’ll probably get to see some fun old games that I’ve forgotten about, and you’ll get to see me play like a complete idiot. It’s a win-win situation!

One problem is that I’m missing a couple years: I don’t have any of my game scores from 1975 or 1976. Stupid me, for not realizing that I would need those game scores 45 years later for a retrospective on something called the Internet. Also, I didn’t play any tournament games at all in 1981 (graduate school, too busy) and 2017 (writing a book, too busy). However, I think I can dredge up a game from every year except those four.

Today we’re going to turn back the clock to 1971, which was year zero of my tournament career. It was the year when Bobby Fischer was rampaging through his candidates’ matches and earning the right to challenge Boris Spassky for the world championship the next year. The “Fischer boom” in American chess was building but not quite here yet. I was twelve years old, and was playing sporadically in my junior high chess club, but really my only opponent was my father.

So that’s where we will begin, with a game against my father played on the day before my thirteenth birthday. Not rated; I didn’t even know yet that a chess rating system existed. I would guess that my strength was about 1200 and my father was about 1400. At this point he was still winning most of our games but I would beat him now and then,.

Walter Nance — Dana Mackenzie, 11/3/1971

(Parenthetical explanation for those who don’t know: my birth name was Dana Nance. I changed my name years later when I got married.)

1. d4 d5 2. c4 Nf6

Back then I played the Marshall Variation because I didn’t know it was supposed to be bad. Nowadays I play it on purpose because it’s not as bad as it’s supposed to be. At worst Black gets a Caro-Kann-ish sort of position.

3. e3 …

Cautious, but it can’t really be bad.

3. … Bf5 4. b4?! …

If I remember correctly, this was a one-game experiment by my father. He wanted to try the idea of just expanding and claiming a lot of territory on the queenside.

4. … e6 5. a3 dc

This move only helps White develop. I think I was intimidated by my father’s clear intention to play 6. c5.

Sometimes, if your opponent goes all in on a “threat,” you should just go ahead and let him do it. Often it turns out to be not such a big deal. Here, even if White does play c5, what does it accomplish? He has squandered several tempi that Black has used for development. The pawn push to c5 is really only good for White if it’s part of an overall clamp that keeps Black’s white-squared bishop in prison. But here, my bishop is developed outside the pawn chain and all my other pieces have good squares too, which is not usually the case in the Queen’s Gambit Declined.

6. Bxc4 Nc6?!

Super ugly, and part of a pattern that I see in both my play and my father’s at this time. When you’re a beginner and learning chess, you play double e-pawn openings and you learn that knights go to bishop three (notably in the Four Knights Opening). Then you start to learn queen pawn openings and you try to do the same thing. But there are many cases where putting the knight on d2/d7 is better. Here, Nc6 is the wrong square because the knight doesn’t have anywhere to go to from there, and even worse it’s a sitting-duck target on both an open file and on a vulnerable diagonal (a4-e8). Nowadays I would automatically play 6. … Nbd7, saving c6 (if necessary) for my pawn.

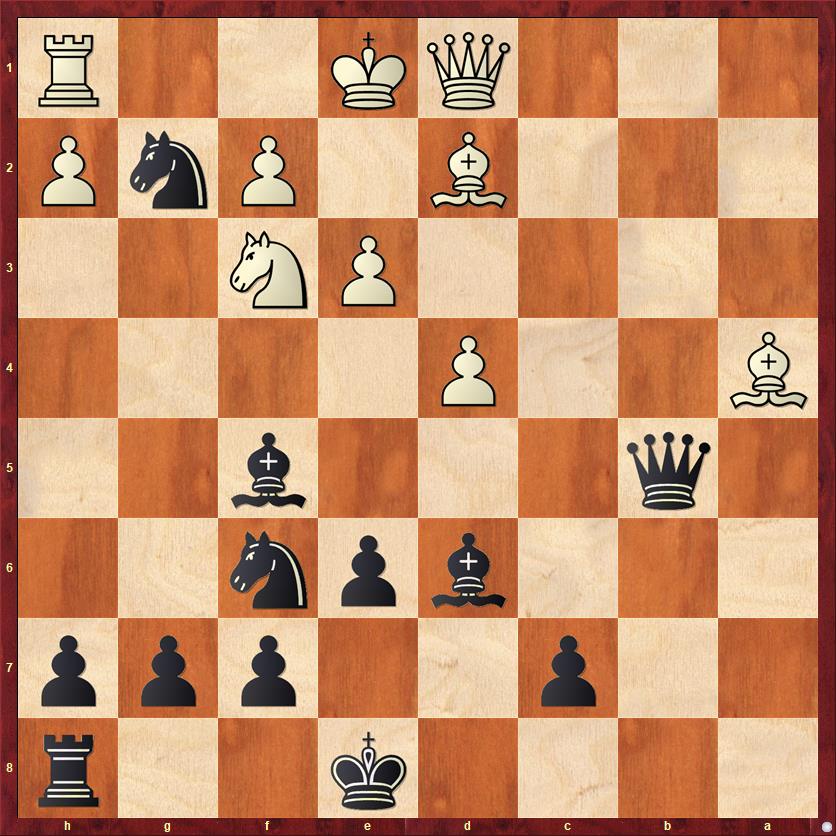

7. Bd2? …

FEN: r2qkb1r/ppp2ppp/2n1pn2/5b2/1PBP4/P3P3/3B1PPP/RN1QK1NR b KQkq – 0 7

My father is showing symptoms of the same disease I had: not knowing when to develop a knight to d2/d7. Here I think that Nd2 and Bb2 is the most logical way to develop the queenside pieces, because neither of them interfere with each other. By contrast, on d2 the bishop interferes with the knight (and the queen), and if the knight goes to c3 it interferes with the bishop.

Mike Splane has commented that it’s remarkable how often you can identify the right move simply by asking which one creates the least conflict between your pieces. In this case, 7. Bd2 is already suspicious because it causes White’s pieces to step on each others’ toes, but it also has a tactical flaw. Do you see what Black can do?

7. … a6?

Not a terrible move, but I failed to spot the tactical opportunity. With 7. … Nxd4! I simply win a pawn, because 8. ed would be met by 8. … Qxd4 forking the unprotected bishop and the unprotected rook. A great lesson for beginners: loose pieces drop off. Note that if White had played 7. Nd2 or 7. Bb2, one of those two loose pieces would have been defended.

8. Nf3 b5 9. Bb3 Bd6 10. a4? …

When going over beginner games, I have to fight the temptation to be hyper-critical. For example, you get a lot of moves like 7. Bd2? a6? where one player makes a mistake but it doesn’t hurt them because the other player is not able to capitalize.

However, 10. a4? is the move that causes White’s position to start spiraling downhill, so I have to criticize it. White is playing a middlegame move when he’s not out of the opening yet. In the opening you have to get your pieces out and get your king to safety. A very common mistake of beginners (and experienced players too, sometimes!) is to open up the position before they have done those two things. In this game, White had lots of chances to castle but he never did, and paid a very steep price.

10. … Nxb4 11. ab ab 12. Rxa8 Qxa8?

More mistakes of inexperience. At this stage of my chess “career” I had never heard of zwischenzugs (in-between moves). So it never occurred to me that I could postpone the “automatic recapture” and play 12. … Nd3+ instead. This stops White from castling and puts the knight on a dominant square. By playing the automatic recapture I let White off the hook. He can now castle and have a bad game, but not a catastrophic one.

13. Nc3? …

Hard to explain this mistake. Even a beginner should know that it’s time for White to get his king to safety. Once again we have a case of canceling errors, where my inaccurate move order on move 12 didn’t really hurt me.

13. … Nd3+ 14. Ke2 Qa6

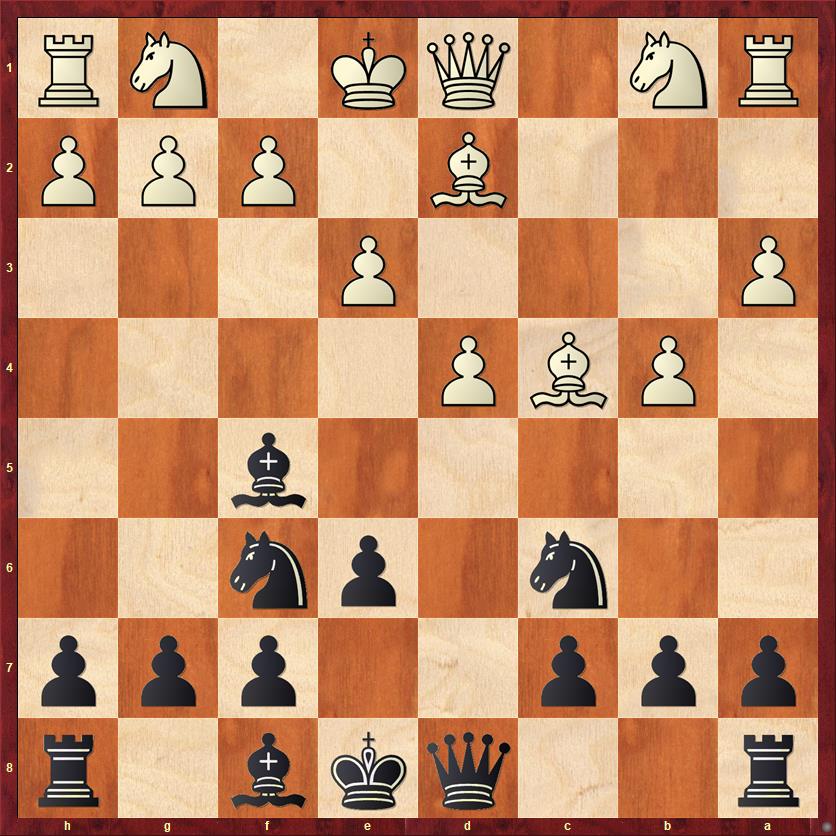

FEN: 4k2r/2p2ppp/q2bpn2/1p3b2/3P4/1BNnPN2/3BKPPP/3Q3R w k – 0 15

Now we get to the neat conclusion of the game (and the reason I saved the game score all those years ago). See if you can figure out how the game ends. My father plays a move that he thinks is setting a trap for me. I “fall into the trap” on purpose, and my father’s cleverness backfires on him in a rather spectacular way.

Have you figured it out?

Here goes:

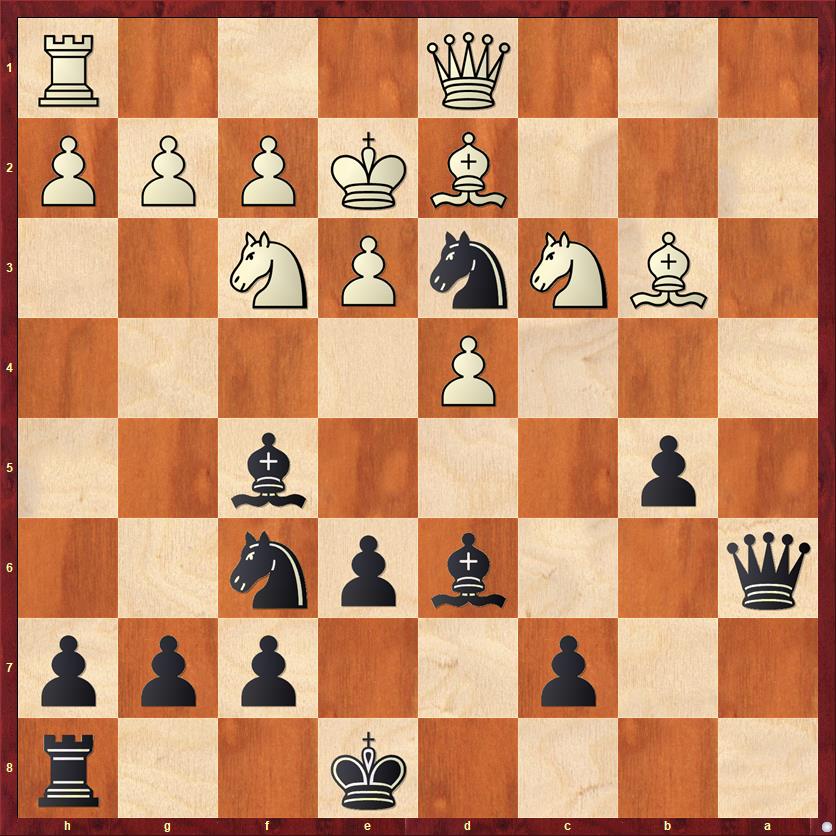

15. Nxb5?? …

This seems to win a pawn. But…

15. … Qxb5! 16. Ba4 …

This seems to win a queen! But I had seen this move coming and had an answer prepared.

16. … Nf4+!

It’s possible that my father missed the fact that this was a double check, so he can’t get out either by taking my queen or by taking my knight. He has to move the king.

17. Ke1 Nxg2 mate

I was so pleased with this that I wrote the position down in my scorebook. I’ll do the same thing here.

FEN: 4k2r/2p2ppp/3bpn2/1q3b2/B2P4/4PN2/3B1PnP/3QK2R w k – 0 18

I was a little bit excited. Here’s what I wrote in my diary: “I BEAT DADDY IN CHESS FOR THE THIRD STRAIGHT TIME! It came with a pinned queen and a knight.” (The word “pinned” was underlined twice, so I suppose that means bold italics.)

Lessons:

- Openings are about three things: Controlling the center, developing your pieces, and getting the king to safety.

- Watch out for making middle-game moves in the opening. What does this mean? It means doing things that do not contribute to the three principles above, in order to achieve other goals like winning material. Of course it’s okay to do these things sometimes, but only if you are quite confident of your calculations and if you suspect that your opponent has made a mistake.

- Loose pieces drop off. So many combinations are made possible by pieces that aren’t defended.

- For beginners: Knights don’t have to go to bishop three. If you can, try to look at games by strong players and see if you can understand when and why they develop their knights to other squares.

- For beginners: Double checks are even more dangerous than ordinary discovered checks, because neither checking piece can be captured.

- For more advanced players: Always think twice before you play an “automatic recapture.” Can you play an in-between move or zwischenzug that makes your position better?

- Often you can tell whether a move is suspicious simply by asking how many of your pieces get in the way of other pieces.

Finally, a question for everybody. Do you think that going over games played by beginners is helpful for other beginners?

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Wow, I started in 1971 too, on my 16th birthday! There aren’t too many Fischer boom kids still playing. My first was a National High School tournament in NYC with Bill Goichberg directing and hundreds of kids gathered around pairing sheets taped to the wall. Some things never change. I actually have my scorebooks from all my years though sometimes there are so many notation mistakes that it’s hard to go through the games. Other than a few years in the 80’s and a very skimpy playing schedule in the 90’s, I’ve been active all that time. I’d like to play next year just to say I hit 50 years but who knows what the future of OTB play is.

I think that for beginners, games played by stronger players are useless. I personally learn nothing from watching online commentary of high level games.

Congrats on your first 50 years! I started playing chess just a little before you (joining the USCF in 1969), so I also recently marked 50 years at the chessboard.

Though rudimentary, I think such games are very useful for beginners, and even as reminders sometimes for experienced players. A game such as this has more good teaching info in it than, say, Ding Liren’s win over Caruana when Fabi forgot his home analysis at move 16…

I would also add that the move … Nc6 in queen’s pawn openings is a real bugaboo for most beginners. Even though this move is often justifiable (as is Nc3 for White in 1 d4 openings), I’ve taken to the statistical approach and simply tell my students “don’t do this!” Besides the reasons you give, I also make explicit the need in QP openings for the Black c-pawn to be mobile, whether to support the center with … c6 (as you state), attack the center with … c5, or even to give the Black queen some “room to move.”

May all your future 49 (or 45) game posts be as instructive as this one!

I am currently coaching two elementary school kids (via Zoom) and they definitely feel that looking at games by beginners is useful, perhaps more useful than looking at better games. They can understand why the players’ mistakes were mistakes, and that encourages them. They can find improvements whose superiority is fairly easy to establish, too.

Today we did a master game instead, and while they appreciated the sudden violence of the final combo (and one of them suggested the winning queen sack, though not its motivation) they were puzzled by much of what led up to it. “Neither player is bringing his pieces to the party,” one kid said, “and why isn’t Black castling?” (Black won.)

A study partner (in India–what a weird world we live in!) and I recently played through the first half of Chernev’s _Logical Chess_ and were struck by his choice of very one-sided games. Most current master games are not one-sided like that; the loser was fighting for counterplay all the time. It’s better chess but less instructive in some ways.