For every good, instructive game that I play against the computer, there must be two or three really awful games. Here’s one that I played this morning that is so bad that it’s good. I’m playing White, Fritz (with its rating set to 2025) is playing Black, clocks are set at 10 minutes for 40 moves, and I’m in very good shape time-wise, with 4 minutes left for 12 moves.

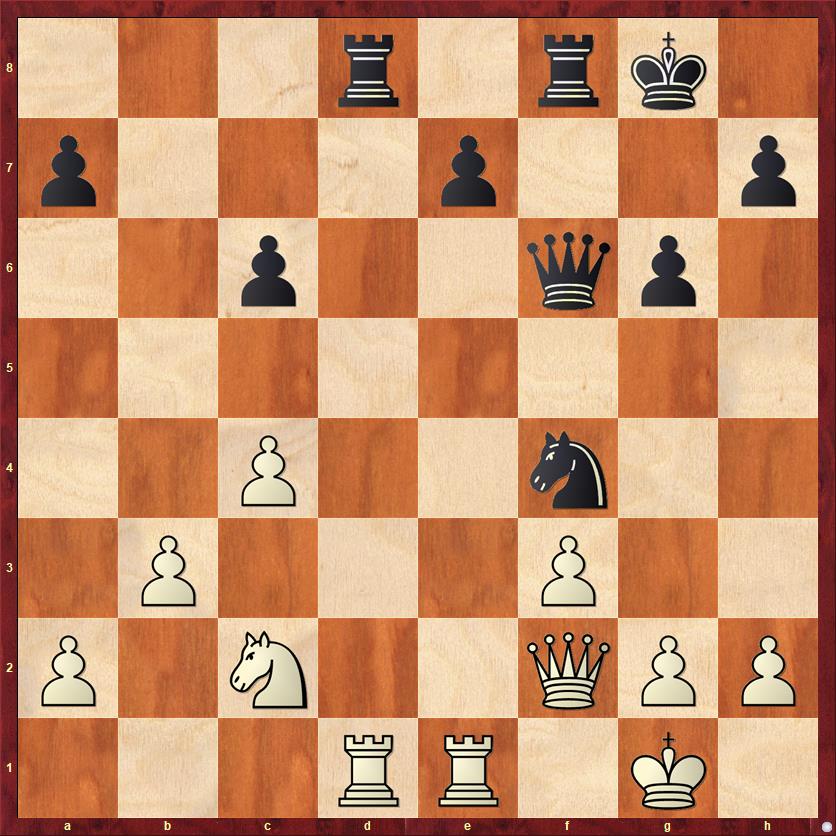

FEN: 3r1rk1/p3p2p/2p2qp1/8/2P2n2/1P3P2/P1N2QPP/3RR1K1 w – – 0 29

Question 1: What is Black’s threat? What should White do about it? Here are three choices, Larry Evans-style: A) 29. Qxa7; B) 29. Qe3; or C) Ne3.

Made your selection? Let’s see…

A) 29. Qxa7? is too greedy. White first needs to take away Black’s counterplay and try to exchange some pieces. Once the position gets stabilized, all of those weak Black pawns will be ripe for the picking. More concretely, after 29. Qxa7? Black can play 29. … Rxd1 30. Rxd1 Nxg2!, the point being that after 31. Kxg2 Qxf3+ the rook on d1 hangs.

B) is correct! 29. Qe3 prevents Black’s main threat, which is … Nd3. It also keeps an eye on f3, so that the “sucker punch” … Nxg2 doesn’t work. It’s important to note also that after 29. … Qg5 30. g3 Rxd1 31. Rxd1 Nh3+ doesn’t win for Black because White’s queen is defended by the knight. Black doesn’t have any apparent ways to turn up the pressure, and Fritz evaluates the position at +2 pawns for White.

C) I was absolutely blind to everything that was going on in the position and I played 29. Ne3?? I guess to be more accurate, I was thinking strategically when I needed to pay attention to tactics. I wanted to maneuver my knight to g4 and e5, and forgot to consider what my opponent might want to do.

Of course, the computer played 29. … Nd3, which wins the exchange. At this point I thought that I had blown the game. But actually, Fritz still evaluates the position as equal! I decided to put up the best fight I could, and I played 30. Ng4 Qg7 31. Qxa7. It’s funny how a move that was previously too reckless is now the best chance to survive.

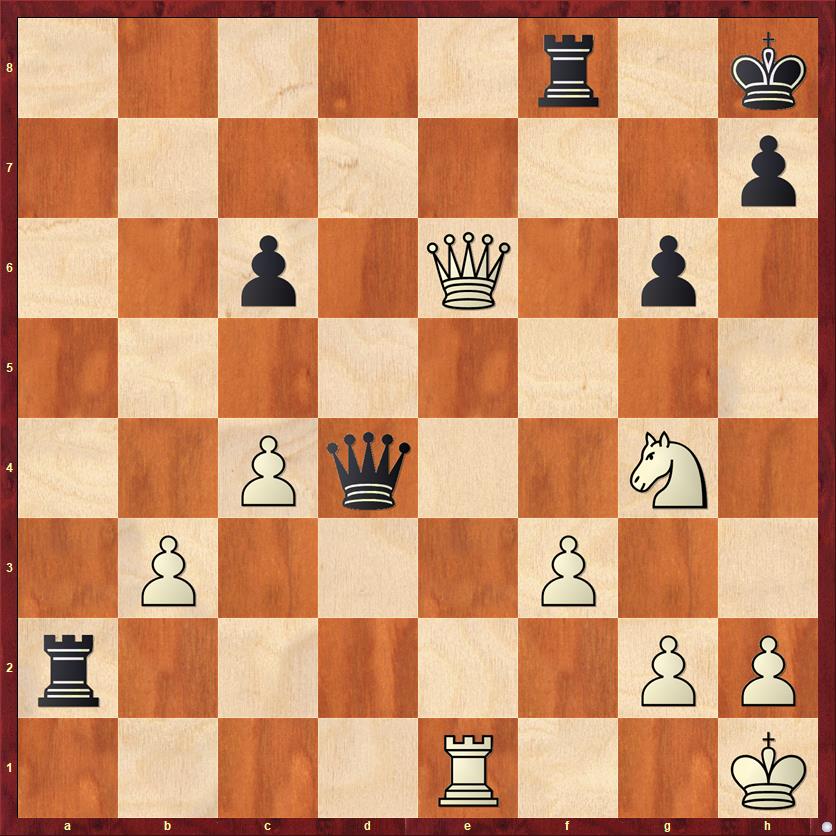

Play continued 31. … Ra8 32. Qxe7 Nxe1 33. Qe6+ Kh8 34. Rxe1 Qd4+ 35. Kh1 Rxa2, reaching the position in the second diagram. Fritz still evaluates the position as even.

FEN: 5r1k/7p/2p1Q1p1/8/2Pq2N1/1P3P2/r5PP/4R2K w – – 0 36

Question 2. Again proceeding Larry Evans-style: Which move do you think gives White the best chances to draw: A) Qe7; B) Qe5+; or C) Qxc6?

A) 36. Qe7 is the move that Fritz recommends. If Black plays aggressively with 36. … Rfa8, then 37. Ne5 Ra1 38. Qf6+ is an immediate draw. If Black tries to trade queens with 36. … Qg7, then White will insist on keeping queens on the board with something like 37. Qe3. I am a little bit nervous about White’s position after 37. … Ra1 38. h4 Rxe1+ 39. Qxe1 Ra1 40. Kh2, but Fritz continues to see it as dead even, 0.00. The key point, I think, is that as long as queens stay on the board it is hard for Black to play aggressively, because the queen and knight work very well together and they can whip up a perpetual check or even a checkmate in almost zero time if Black leaves his king unguarded.

B) I think that 36. Qe5+ is an extremely interesting idea and may actually hold the draw as well. The strategic objection is that by trading queens, White gives up any chance at counterplay. However, White has a different idea in mind here: to win Black’s c-pawn and then set up a fortress on the kingside. The computer (typically) fails to understand this idea. Thus, after 36. Qe5+ Qxe5 37. Nxe5 Rb8? it gives Black a 0.95-pawn advantage. In reality, I think it’s a draw after 38. Nxc6 Rxb3 39. h4 Rbb2 40. Rg1 Kg7 41. Ne5 Kf6 42. Nd3! (the knight is heading for e4) 42. … Rc2 43. Nc5 Rxc4 44. Ne4. Black has no pawn breaks and no apparent way to target any of White’s pawns.

I think that a better try after 36. Qe5+ Qxe5 37. Nxe5 is … Re8. Notice that it sets a trap: if White tries to win the exchange with 38. Nf7+?? Kg7 39. Rxe8, he will get checkmated after 39. … Ra1+. So White has to leave his knight on e5. Meanwhile, Black’s idea is to move his pawn to c5 and then try to win White’s b- and c-pawns. I believe that Black can win the b-pawn, but as long as White can maintain his knight outpost on e5, I don’t see how Black is going to win the c-pawn. I’d be really interested in seeing GM’s play this endgame! The bottom line is that line B is probably not quite as good a choice as line A, because it condemns White to an extremely long and passive defense, but if you have a taste for that sort of thing, you may still be able to hold a draw.

Instead I once again played a move that shows I had no clue what was going on: C) 36. Qxc6?? The funny thing is that I was almost certain that “pawn-grabbing” was not going to be the way to draw, but I did it anyway. I guess the reason was that I still thought I was objectively losing, and so my best chance was to wipe out as many Black pawns as possible in case something strange happened. And guess what? Something strange did happen.

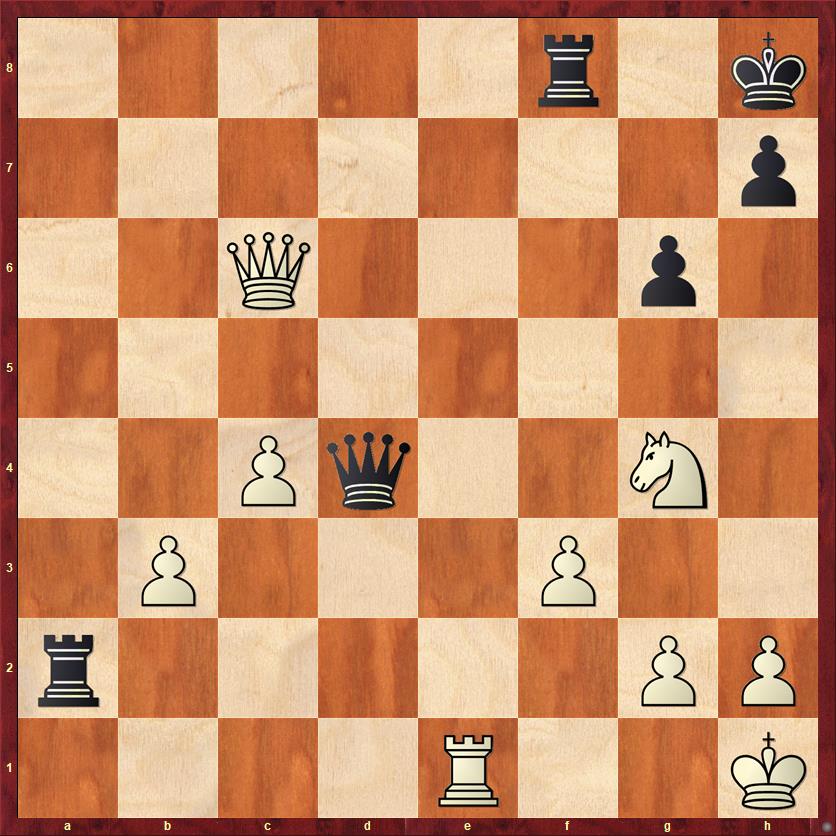

FEN: 5r1k/7p/2Q3p1/8/2Pq2N1/1P3P2/r5PP/4R2K b – – 0 36

Question 3. What is the best move for Black? Your choices are: A) 36. … Re2; B) 36. … Ra1; or C) 36. … h5.

Got your choice locked in? Let’s see how you did.

A) 36. … Re2? is the move that I feared, and the move the computer played, but it is the wrong move. After 37. Rg1 Black is certainly better but the win will still take a long time.

B) 36. … Ra1! ends the game almost immediately. White has no place to run to with his rook (note in particular that Rg1 is not available here as it was in variation A), so he has to defend with 37. Qe6. Then 37. … Rxe1+ 38. Qxe1 Ra8! threatens … Ra1 and there is nothing White can do about it. I love the geometry of this variation and the way the queen on d4 orchestrates everything, controlling the squares g1 (so White’s rook can’t go there) and a1 (so that White can’t keep Black’s rooks out of there).

C) 36. … h5? is similar to what happened in the game. Yes, it wins White’s knight, but it also leaves Black’s king exposed to a blizzard of checks. It’s definitely more difficult than necessary.

So what happened in the game was 36. … Re2?, as I said above. Of course, White can’t take on e2 because of the back-rank mate. If a human made this move I would say it was a case of hubris: the human wanting to play the “clever” move instead of the ruthless winning move 36. … Ra1! This is one of Dana’s Chess Aphorisms: Ruthlessness beats cleverness, every time.

Since it was a computer that played the move, all it means is that I had Fritz set to a rating of 2025, which means that it occasionally blunders. In this case, it picked just the right time. Like I said in the title: anti-chess.

The game continued 37. Rg1 h5?! 38. Qxg6. (Here, an interesting improvement is 38. Nf2! Rxf2 39. Qxg6, when Black cannot both defend the h-pawn and stop perpetual check. Fritz gives 39. … Qf4 40. Qxh5+ Kg7, reaching an amazing position with five pawns against a rook. But White has run out of checks, and I have to think that Black will ultimately win.)

Black played 38. … hg 39. Qh6+ Kg8 40. Qg6+ Qg7 41. Qxg7+ Kxg7 42. fg. Here, too, we have gotten a position where White has five pawns for a rook. However, unlike in the other variation, the queenside pawns are dead meat, and it’s going to become three pawns versus a rook very shortly. But we have one more outbreak of anti-chess to contend with.

42. … Re3 43. h3 …

Finally stopping the back-rank mate threats. There was no point in “defending” the b-pawn with 43. Rb1 because it doesn’t actually defend: 43. … Rxb3!

43. … Rb8 44. Rc1 R8xb3 45. Kh3 Rbc3 46. Ra1 Rxc4 47. Ra7+ …

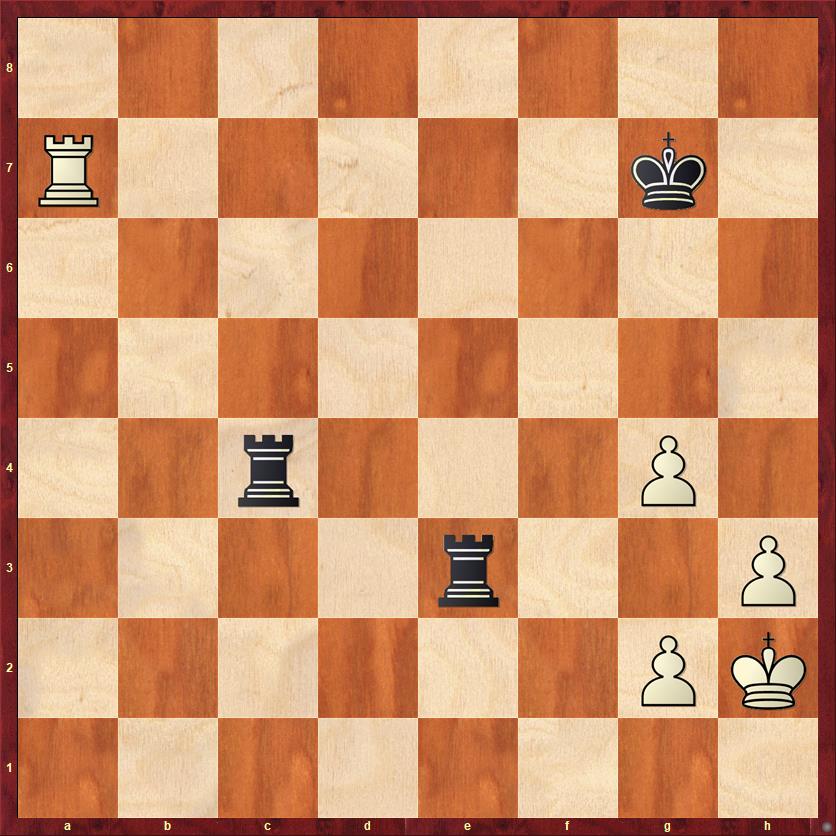

FEN: 8/R5k1/8/8/2r3P1/4r2P/6PK/8 b – – 0 47

And now the last crazy thing happened, which I think is not due to Fritz being “dumbed down” to 2025 but more a problem with computer chess in general. Fritz evaluates the position at +3.5 pawns for Black but it cannot come up with a winning plan. It just keeps on moving its king around, thinking it has a 3.5-pawn advantage but doing nothing to actually realize that advantage. The anti-climax to the anti-chess game was as follows:

47. … Kg6 48. Ra6+ Kg5 49. Ra5+ Kf6 50. Ra6+ Ke7 51. Ra7+ Kf6 52. Ra6+ Kg5 53. Ra5+ Kh6 54. Ra6+ Kg7 55. Ra7+ Kf6 56. Ra6+ 1/2 – 1/2

We had the same position on moves 50 and 52.

Question 4: Is the position in the last diagram actually a win for Black? If so, describe Black’s winning plan. Do what the computer couldn’t do!

Lessons:

- Never forget to ask yourself what your opponent is threatening.

- Don’t give up too soon. Remember that quote from Jesse Kraai that has become (unintentionally) a permanent fixture at the top right of my blog page. (I originally intended to rotate new quotes in regularly, but it was too much trouble, and Jesse’s quote is too good to take down!)

- When ahead in material, your first priority is to eliminate your opponent’s counterplay, not to grab more material.

- Ruthlessness always beats cleverness. A simple and overwhelming winning line is better than a “brilliant” combination that may backfire.

- If you’re trying to hold a draw in the endgame, you should generally prefer a line that gives you some kind of counterplay. Completely passive variations should generally be avoided, except…

- Some endgames can be saved by “building a fortress.” Aim for a position with all the pawns on one side of the board, no pawn weaknesses, no pawn breaks for your opponent, and no entry squares for his king. Examples where this can occur are N+P versus R, B+P versus R, and R+P or R+2P versus Q.

- Evaluation is worthless without a plan. If you don’t have a plan, don’t even talk to me about how winning your position is.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

The ultimate challenge for a computer is to equal Polugaevsky’s analysis and win the endgame Polugaevsky – Geller (Skopje, 1968), at move 43 White.