During the Pro Chess League season this year (which still has not ended, by the way — the finals have been postponed until September) Robert Hess made a comment that jolted me awake. “When I’m evaluating a position,” he said, “The first thing I look at is who has the pawn breaks?”

What?! The first thing I look at is who is ahead in material. Pawn breaks may come fifth or sixth, or maybe even lower than that, on my personal list. But Robert Hess is a grandmaster. I am not. Ergo, it would behoove me to listen to him.

Hess’s point is that the player who has more playable pawn breaks has more control over the evolution of the position. It’s a tremendous advantage to have. Imagine that you’re in a race and you have the right to change the course, say by opening up a shortcut. You could even be behind, but if you have the shortcut advantage you can catch up.

The definition of a “playable” pawn break can be quite loose, and this is one of the subtleties in the concept. Often pawn breaks may look unplayable — they cost you a pawn — but they change the position in important ways, opening a line for your pieces or closing lines for your opponent’s pieces. Or they may weaken your opponent’s pawn structure and create targets for you to attack.

Recently I lost a game against my computer in which I missed not just one but four pawn breaks that would have given me excellent attacking chances. Ironically, the one time I did play a pawn break was the wrong time, and it didn’t do very much to improve my position.

This is another humiliating game for me because I lost a very superior position. But I’m showing this game not to humiliate myself, but to show you how to improve your game. (For the record, I do think I would have played some of these pawn breaks in a tournament game. But the fact that I could not find them when playing a blitz game means that they are not the first thing I think about, as Robert Hess says they should be.)

Fritz 17 — Dana, 40 moves in 10 minutes

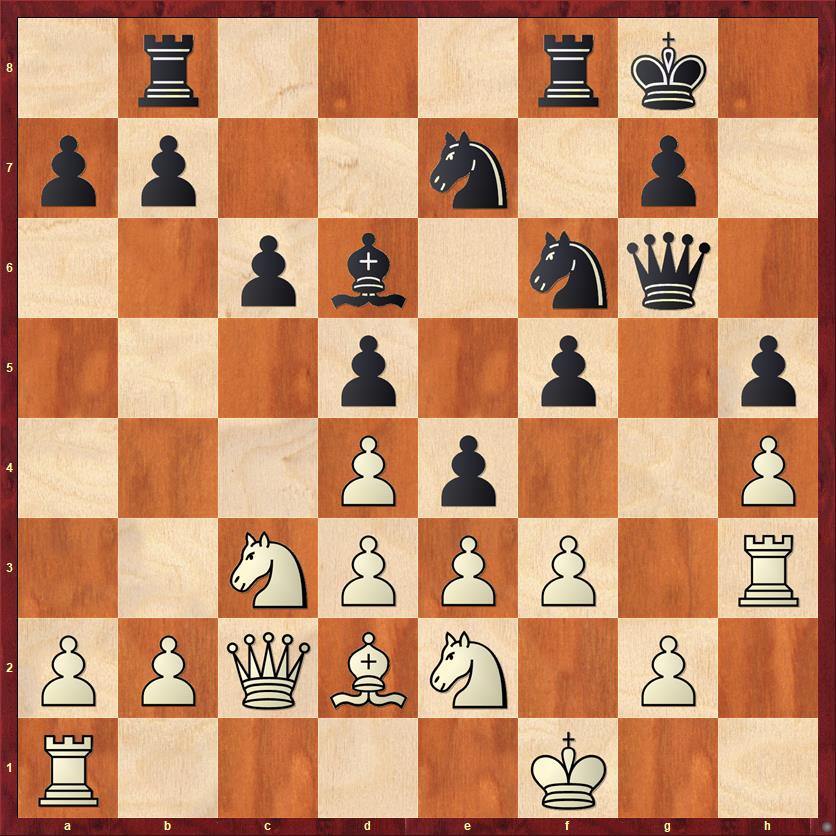

FEN: 1r3rk1/pp2n1p1/2pb1nq1/3p1p1p/3Pp2P/2NPPP1R/PPQBN1P1/R4K2 b – – 0 18

As usual Fritz played a super funky opening, which I’ll skip, and we will start on move 18. Who has the advantage in the above position? Let’s think about the position Robert Hess style. Who has the pawn breaks?

Well, White has essentially zero pawn breaks. The move g4 is never playable because it opens lines that Black can use to attack the White king. Over the very long term White has two possible breaks with b2-b4-b5 and a2-a4-a5-a6, but these take a long time to carry out and are not exactly terrifying.

How about Black? Well, he has a pawn break with … c6-c5 that may be good at some point but isn’t good yet. And he has a break with … f5-f4 that is like a hand grenade. You’d better pick the right time to pull the pin, but it can do a heck of a lot of damage. So Black has two pawn breaks, and one of them is kind of meh but the other should be checked carefully on every single move.

What if we play it now? Here’s where beginner chess is a lot different from master chess. The beginner looks at 18. … f4 and says, “You can’t play that, because it’s attacked 3 times and only defended once.” But the master says, “Please! Go ahead and take it!” And after the beginner plays 19. ef (or Nxf4 Bxf4 ef), Black plays 19. … ed, forking White’s king and bishop. Here we see the idea of a sweeper; the move 18. … f4 swept open the a2-h7 diagonal and increased the pressure on White’s d3 pawn.

Then the beginner says, “Okay, you got me there, but you still can’t play 18. … f4 because the e-pawn is attacked 4 times and only defended 3 times. So I’ll play 19. de instead.” The master says, “Make my day!” and plays 19. … fe 20. Bxe3 Nxe4. Not only has Black swept open the a2-h7 diagonal, he has also swept open the f-file. So the knight cannot be taken by the f3 pawn, and meanwhile it threatens 21. … Ng3+, with a discovered attack on White’s queen. If White tries to break the pin with 21. Kg1, now Black has 21. … Ng5! 22. Qxg6 Nxh3+! So 21. Nxe4 looks forced, and after 21. … de 22. Kg1 Black can obliterate White’s kingside with 22. … Rxf3.

Moral: When determining whether a break is “playable,” don’t just count the attackers and defenders. Look at all the ways in which the move changes the position.

Instead, I played the less accurate

18. … de 19. Qxd3 Ne4

It’s interesting how I have the right themes in mind, but they aren’t as effective in this move order. The move Ne4 was much more forceful in the previous line, where it took a pawn and threatened a discoverd attack on White’s queen.

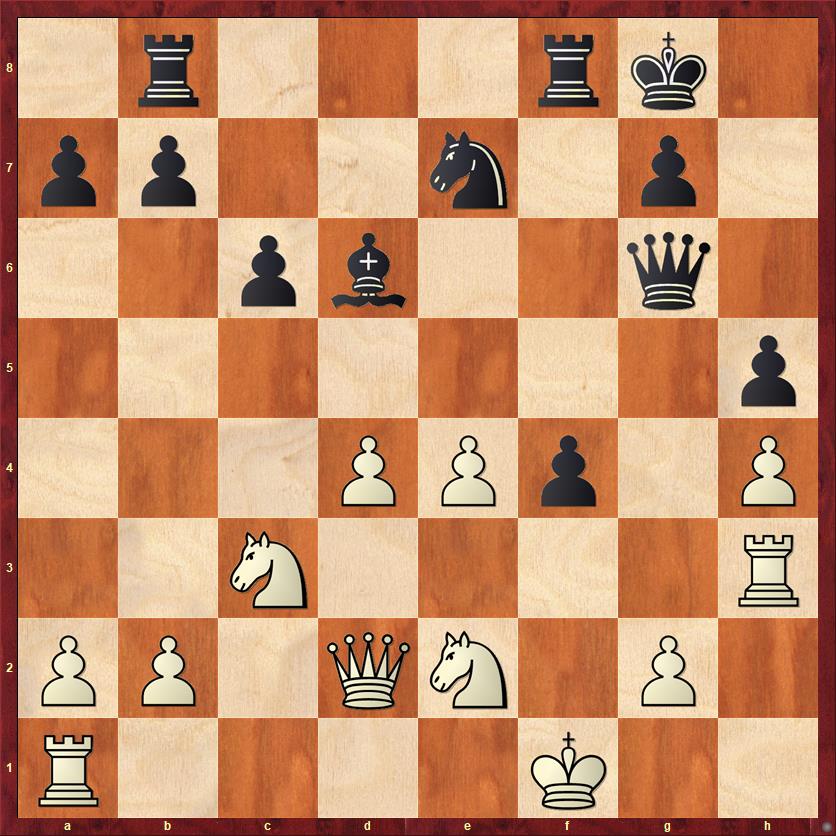

20. Qc2? …

This gives me another shot at our favorite pawn break…

20. … Nxd2?

Which I whiff on again! Once again, 20. … f4! blasts open lines, and all the tactics favor Black. If 21. fe fe+ wins back the piece and opens up lines against White’s king. If 21. ef Ng3+ wins the queen with a discovered check (one reason that 20. Qc2 wasn’t so good).

21. Qxd2 f4?!

Ironically, when I finally played the pawn break it was no longer a clear winner. My thinking was that after 22. Nxf4 Bxf4 23. ef Nf5 my knight is taking aim at a lot of weak points in White’s position: h4, g3, e3, d4. But nothing really clear comes out of it after, say, 24. Re1 Qf6 25. Re5 Nd6 (threatening Nc4) 26. Rxh5 Qxf4 27. Qxf4 Rxf4. It feels as if Black has given away his advantage.

However, Fritz decided not to accept the pawn and instead played

22. e4 de 23. fe …

What do you think we should do here? All together now…

FEN: 1r3rk1/pp2n1p1/2pb2q1/7p/3PPp1P/2N4R/PP1QN1P1/R4K2 b – – 0 23

PAWN BREAK!! Now is a great time for 23. … f3!, forcing open the f- and g-files, which are exactly the files that White does not want to have opened. If 23. … f3 24. Rxf3 (or gf) Qg4 Black will win back the pawn for sure and probably more with the idea of … Ng6, …. Nxh4, etc.

Instead my attention was focused on the wrong part of the board. I saw White’s pawn duo on d4 and e4 and thought that I wanted to reposition my bishop to I could put more pressure on them. So I played

23. … Bc7,

not a horrendous move but still a missed opportunity. Fritz answered

24. Qd3 Rbd8 25. Rc1 Qg4 26. Nd1.

Hmm, what do you think that Black should do here? All together now…

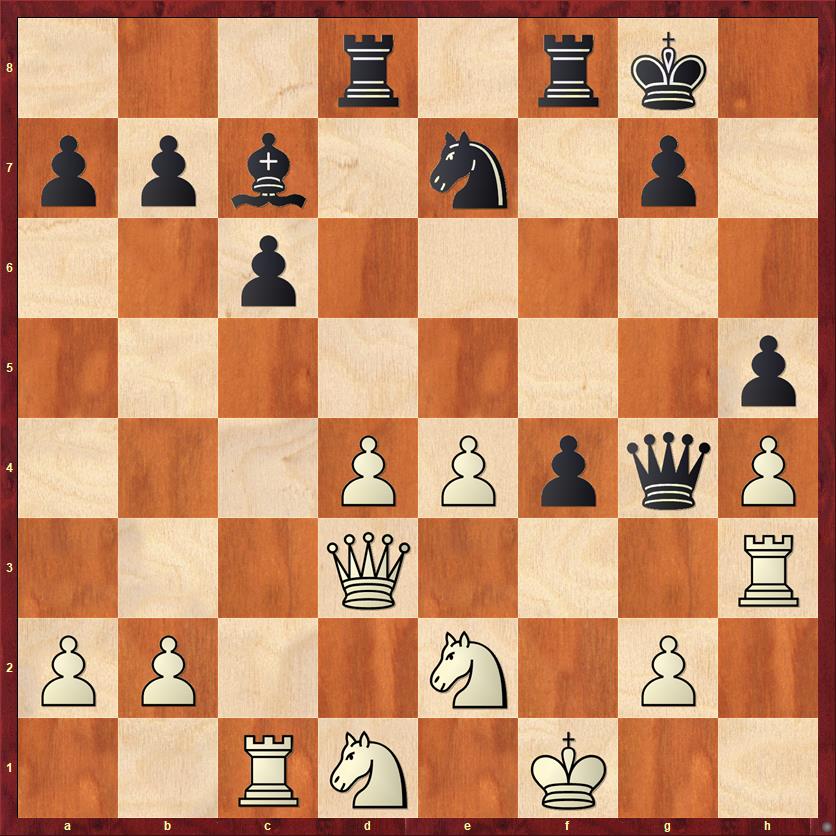

FEN: 3r1rk1/ppb1n1p1/2p5/7p/3PPpqP/3Q3R/PP2N1P1/2RN1K2 b – – 0 26

PAWN BREAK!!!! The position is crying out for me to play 26. … f3! How could I miss it?

It’s perfectly set up. White can’t ignore the threats to take on e2 or f2. He has to take the pawn. He can’t take with the queen, obviously. He can’t take with the pawn, obviously. So there’s only one move to look at, 27. Rxf3. And then after 27. … Rxf3+ 28. gf Rf8, Black has tons of targets: f3, h4, the weak dark squares on the kingside.

Instead I played a move that was too slow, and White’s counterattack came like a punch from behind. I never saw it coming.

26. … Ng6?? 27. Qb3+ Kh7 28. Nf2 …

This surprised me because I thought it would just take on b7. As usual, I failed to understand what the computer was doing.

28. … Qc8 29. Rc5! …

And my jaw hit the floor. There’s no way for me to defend the h5 pawn!

29. … Kh6 30. Qf3 …

I’m just dead here. I might as well resign, but I played a couple more moves out of inertia.

30. … Ne5 31. de Bb6 32. Nxf4 Rxf4 33. Qxf4+ resigns

Well, I apologize you for showing so many mistakes. It is just a blitz game, after all. But I hope I have learned a lesson — to make the pawn breaks the first thing I look at, not the last.

{ 7 comments… read them below or add one }

I guess with …Ng6 you didnt’ ask yourself the question: “What are the drawbacks of this move?”

1. less control over d5. not a problem, if white plays d5 then black can just take, and white will be left with a isolate pawn.

2.less control over f5. not a problem.

3. stops me playing g6. only a problem if h5 can be attacked. Rc5 attacks it once, the queen can be chased away with Nf2…. More calculation needed here.

did you consider point 3 at all?

did you just miss the Rc5 possibility?

Do you ask yourself what are the drawbacks when you make moves?

No, I completely missed the whole Rc5 idea. That is, of course, one reason that the computer played Nd1. I only saw it as a repositioning move to be followed up by Nf2… I had no idea that it was actually setting up Rc5.

A couple points here. First, I think that rook lifts, especially long rook lifts (to the fourth, fifth, or sixth rank) are psychologically somewhat difficult to see. At least for me. I’m not sure why, and this is something that might be worth exploring in a post.

Second, when playing tournament chess I do of course think about drawbacks, and I also ask myself more often, “What is my opponent trying to do?” But these rapid games show that this part of my thinking process tends to break down when I am under time pressure.

regarding the difficulty to see moves. For me I am biased towards: “rooks and bishops are long range pieces”, so it feels awkward to put them on squares adjacent to enemy pieces.

Another aspect is just lazyness. When advancing a rook up the board, you have to consider all the ways the opponent can attack the piece and all the free tempos you are giving him, further you need to make sure that your opponent can’t create a “mating net around the rook” it’s just a lot of extra calculation that I’m reluctant to do as it lowers my enjoyment of the game.

An analogy that I like to use regarding pawns and pieces. Is that pawns make up the battleground and the pieces are the military units that operate on that battleground. So before choosing where to deploy your forces you must make sure the battleground can’t change.

I wonder if it is inherently harder for pawn moves to come to mind when calculating, given their unique movement/capture pattern. Am I the only one that tends to miss pawn resources in tactical puzzles surprisingly often? It seems to get worse after taking some time off from chess.

There may be a tendency to underrate pawn moves because the pawn seems like such a weak and insignificant piece. That’s why it is really important to keep Hess’s comment in mind. Another analogy is that each pawn break starts a new chapter of the game.

In the initial position the pawn on f5 is a “traitor pawn”, to use my terminology. It blocks the activity of the rook on f8, the queen on the diagonal and the e7 knight. Black would be better off without it. It’s not surprising that pushing it to f4, even as a sacrifice, is a good idea.

I call situations like this, when you give away a pawn to open a line ” losing a pawn but gaining a rook. ” It’s a key idea in many of my games. Most chess players are familiar with this theme if they play the Benko gambit.