With nothing much going on the world of chess, I’ve been playing against my computer a lot. It’s a bad habit, really. But one somewhat unexpected benefit is that I’ve gotten to play a few interesting endgames recently.

When I play against Fritz, I generally set it on “Rated Game,” because that setting allows you to play without kibitzing and without being able to see the computer’s evaluation of the position. It also allows you to set the computer’s strength. Lately I have always been setting it at 2025, which seems to be a good challenge for me. Finally, I set it at 40 moves in 10 minutes. Call me a traditionalist; I like having a lot of time to think after the 40th move. It’s enabled me to win games that I would not have been able to win in a blitz time control. But at the same time, it’s pretty fast, so I can usually finish a game in half an hour.

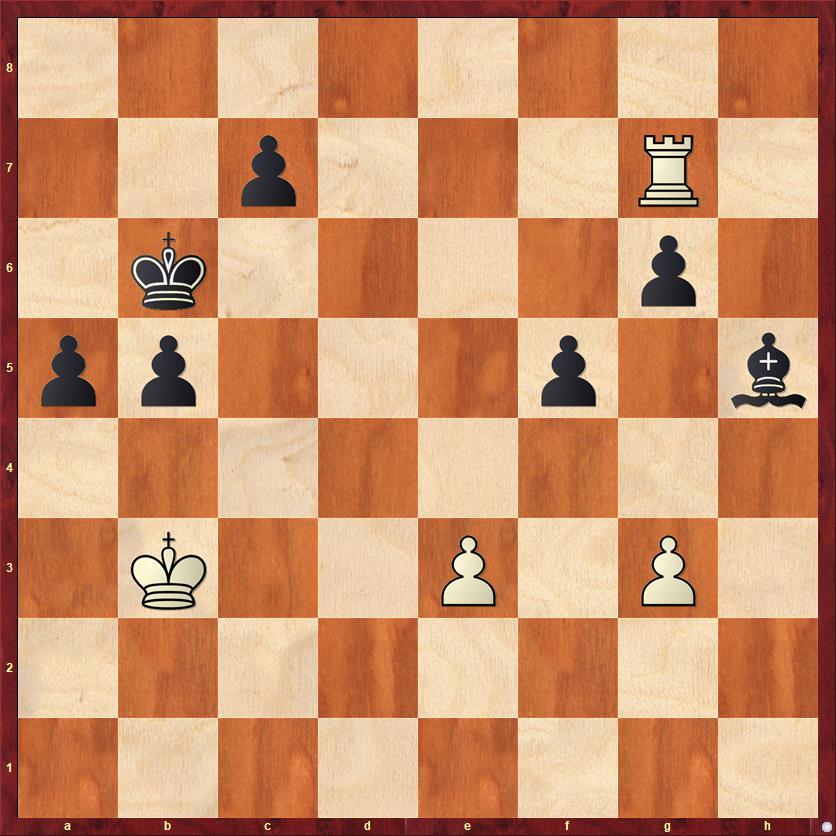

FEN: 8/2p3R1/1k4p1/pp3p1b/8/1K2P1P1/8/8 w – – 0 37

The position you’re looking at exemplifies my struggles against the computer. I was Black, and when you look at the position you will of course say, “Black is completely winning!” It’s inconceivable that the game could end in anything other than a Black victory.

But… White was a computer. And even “dumbed down” to 2025, Fritz will try every trick in the book, and a lot of tricks that aren’t in the book. And… Black was a human. Me, in time trouble, with half a minute left to play 4 moves.

So, when the computer played 37. e4!, I didn’t stop to think about what it was doing or why. If I had thought for even a few seconds, perhaps I would have realized the need to get my bishop to safety with 37. … Bd1+. After 38. Kb2 fe 39. Rxg6+ c6 it’s true that I will need to worry a little bit about White’s passed g-pawn, but my flotilla of passed pawns should easily decide the game in my favor.

But instead I played 37. … fe?, walking right into the computer’s cheapo: 38. g4!

Oh, so that’s the point! There’s no saving the bishop. At this point I had a complete emotional meltdown. That’s another difference between humans and computers. They aren’t prone to meltdowns.

I thought I had blundered the game away, but in fact Black should still draw easily. The best way to do it is to continue “falling into the trap” on purpose with 38. … Bxg4 39. Rxg6+ Kc5 40. Rxg4 Kd4. There’s no way on Earth that Black should lose this game; in fact, the question is whether White can actually stop the four passed pawns. According to Fritz, the drawing plan is to move the rook to the eighth rank and play checks from behind. If Black moves his king in front of the e-pawn to escape the checks, then White plays Rc8 attacking the c-pawn. If Black defends with … Kd4, then White plays Rd8+ again, and we have a repetition of position.

But in time trouble I lost all semblance of rational thought and played 38. … a4+ 39. Kb2 c5?

The difference between this line and the previous one is that Black’s king is behind the pawns and too far away from the e-pawn to defend it. So instead of 4 pawns versus rook with an easy draw, we will have 3 pawns versus rook with a very tricky position.

More generally, another moral here is that in most endgames, given a choice between pushing your pawns and activating your king, you should activate your king first.

Okay, let’s move ahead to our next interesting position, which arises after 40. gh gh 41. Re7 b4 42. Rxe4 Kb5 43. Rh4 Kc6 44. Rxh5 Kd6 45. Rh6+.

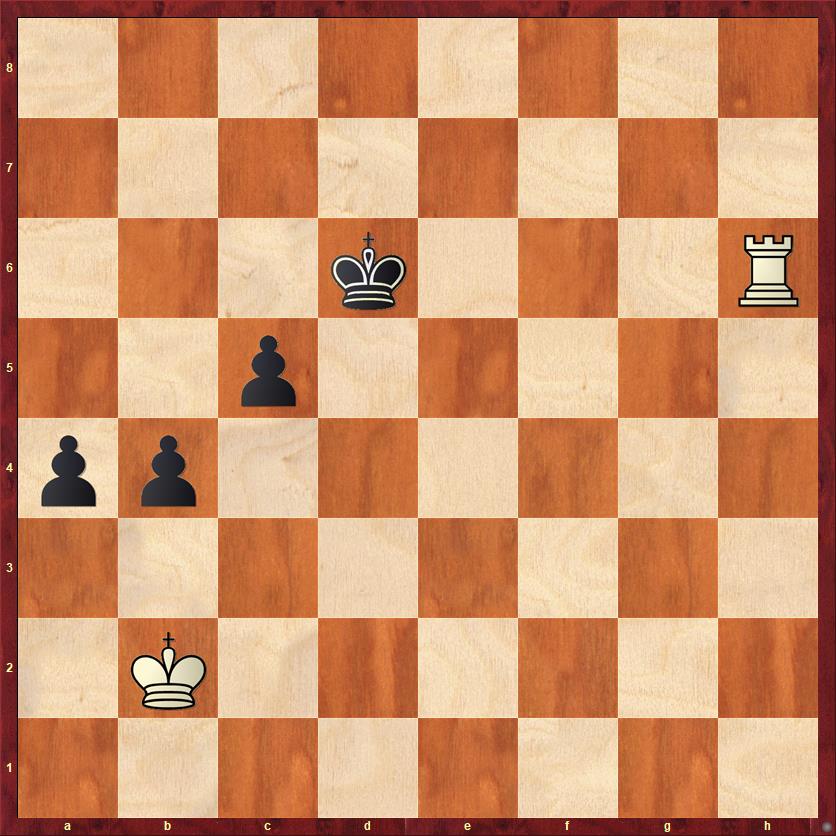

FEN: 8/8/3k3R/2p5/pp6/8/1K6/8 b – – 0 45

Which way do you go with your king?

I’m sure it will be no surprise when I tell you that I went the wrong way. But it’s a really interesting mistake. I played 45. … Kd5?? automatically (I took only 5 seconds on the move), in part because of the moral I just told you about. In endgames, 99 percent of the time you want to make your king as active as possible.

This position is in the one percent of exceptions. The correct move is 45. … Kc7!!, with a tablebase draw. (Also, 45. … Kd7 works, but … Kc7 is the more thematic move.) Yes, the job of the king here is to defend. There is no way that it can get in front of the pawns, so 45. … Kd5 is just useless bravado.

Ironically, the computer blundered a few moves later and gave me a second chance to do the right thing. The game continued as follows:

46. Ra6 a3+ 47. Kb3 Kd4

In for a penny, in for a pound. I had no choice but to continue “activating the king.”

Here the simplest route to victory for White is to cut my king off from the pawns with 48. Rd6+ Ke5 49. Rd1! This is another surprise. We are all used to the mantra, “Rooks belong behind passed pawns.” But here the rook’s job is to protect the first rank. We see why after 49. … Ke4 50. Kc4 Ke3 51. Kxc5 b3 52. Kb4, and White’s king is in time to vacuum up the pawns. (If White had played 49. Rd8, Black would just play b3-b2 and win.)

However, when it is “dumbed down” to 2025 the computer doesn’t always play the best moves, and here it starts drifting a little bit without a plan.

48. Ra7? Kd5 49. Rc7 Kd6 50. Rc8 Kd5 51. Ra8 Kc6!

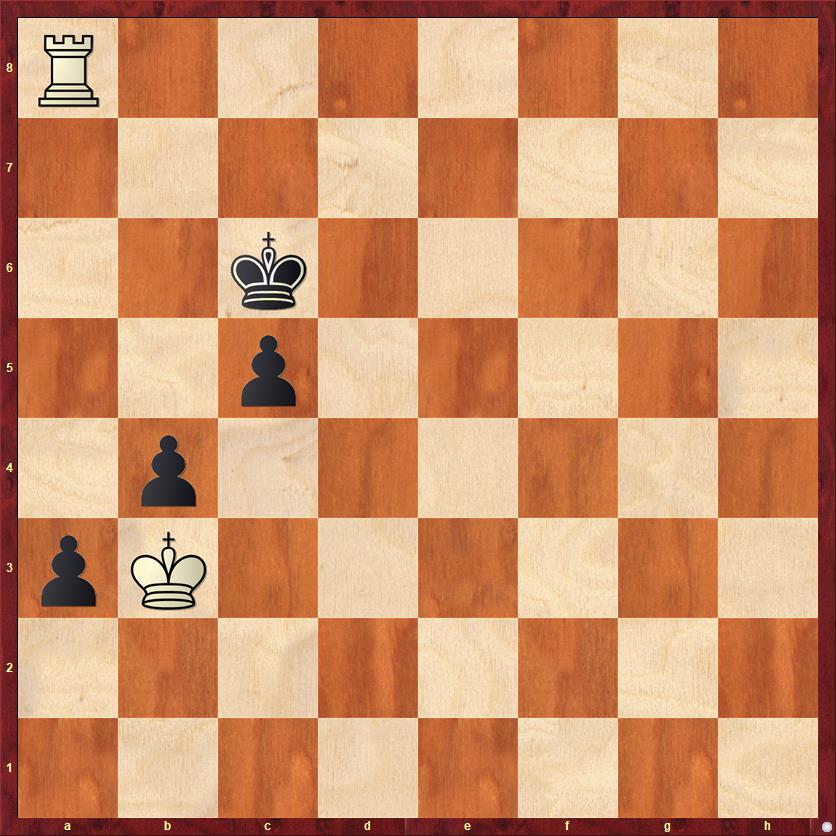

FEN: R7/8/2k5/2p5/1p6/pK6/8/8 w – – 0 52

This is the point where I figured out that the right idea was not moving my king forward, but moving it backward. Although White’s play has not been accurate, he is still winning. There is only one winning plan, though, and it’s far from obvious.

52. Kc4?? …

This natural-looking move is wrong, and leads to a tablebase draw. The correct move is 52. Rb8!! Why this move? The point is that White, of course, wants to win Black’s c-pawn, but he must make sure that Black’s king doesn’t get to b6. If you imagine the position with Black’s king on b6 and White’s king on c4, White can never play Rxc4 because Black would play … a2 and win. A tragedy for White, where his own king gets in the way of the rook, which cannot stop the pawn from queening.

After 52. Rb8!! Kc7 53. Rb5 Kc6 54. Kc4 Kd6 55. Rxc5 b3 56. Rd5+ Ke6 57. Rd1 b2 58. Kb3 we once again have a position where White’s king is just in time to stop the pawns.

52. … Kb7!

Finally the king reaches his ideal square! Black’s king harasses the rook endlessly on the a-file. If the rook moves somewhere on the eighth rank, Black will just play … Ka7-b7-a7 and White cannot make any progress. Amazing!

The game ended quickly with a threefold repetition: 53. Ra5 Kb6 54. Ra8 Kb7 55. Ra5 Kb6 56. Ra8 Kb7 1/2-1/2. Ironically, Fritz evaluates this position at +2.78 pawns in favor of White, but the tablebases show the truth: White has no way to win. (I’m a little bit surprised that Fritz 17 doesn’t come with the 6-piece tablebases already programmed into it. I had to look the position up online.)

Of course, before tablebases there were endgame manuals, and they could not have overlooked such a fundamental endgame as this. In Reuben Fine’s Basic Chess Endgames (1941), he says, “Pawns on 6th, 5th, 4th lose. [Pawns on 5th, 4th, 3rd draw.] Pawns on 4th, 3rd, 2nd win.” He refers to “Handbuch,” which I think must mean Grosses Schach-Handbuch by J. Dufresne and J. Zukertort (1873). So this position and this drawing idea have been known since at least 1873!

Obviously, it would have been better if I had known about the drawing motif in advance. I’m lucky that the computer gave me a second chance, and I’m pleased that I actually did manage to figure it out on the second try. Good things can actually come out of playing against a computer!