The big story in round 5 of the FIDE Candidates Tournament is that we have a single leader for the first time. In a matchup of two of the leaders, Ian Nepomniachtchi of Russia and Wang Hao of China, Nepo took advantage of a subtle mistake by Wang and won.

It was an impressive game by Nepo, who never had much of an advantage as White but nevertheless kept worrying Wang with little threats. Wang’s strategy was just to trade pieces and get to a drawn endgame. But in a complex late-middlegame position, Q+N versus Q+N, Wang put his queen on the wrong square, and Nepo finished with a nice little combination based on the fact that Wang’s king was overworked (defending both the queen and knight).

However, I’m not going to show you that game! The reason is that I think the most fascinating game of the round was the draw played by Kirill Alekseenko (White) and Maxime Vachier-Lagrave (Black). This game featured daring attack and defense, with pieces being sacrificed by both players all over the board.

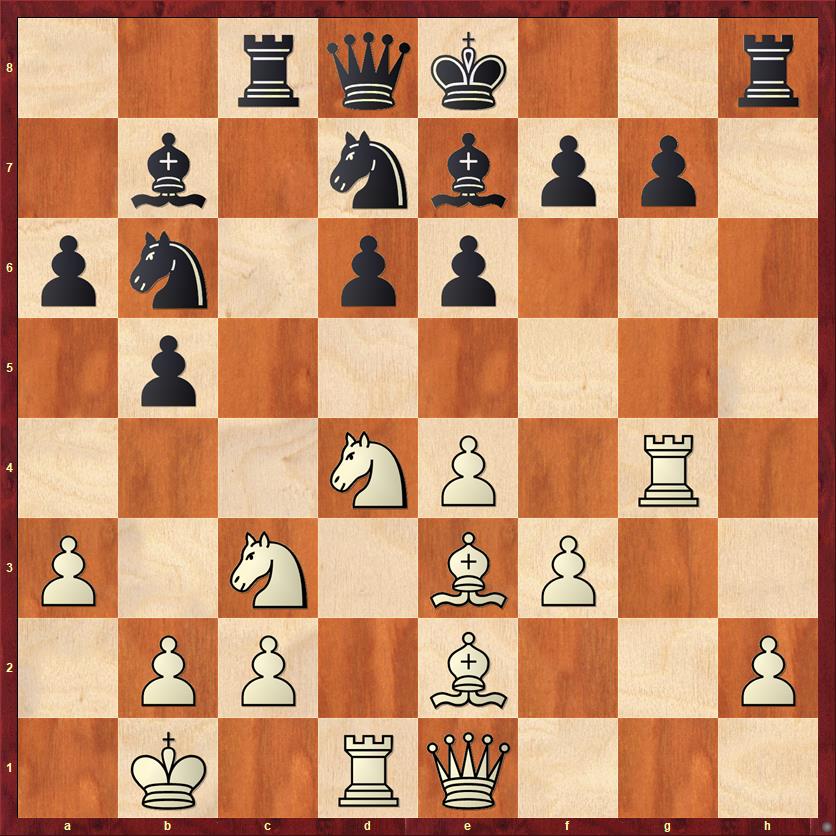

FEN: 2rqk2r/1b1nbpp1/pn1pp3/1p6/3NP1R1/P1N1BP2/1PP1B2P/1K1RQ3 b k – 0 16

Here is the position where everything exploded. Interestingly, MVL had reached the same position as Black against Magnus Carlsen in December. In that game he played 16. … Bf8, because he thought that 16. … g6 would simply lose to 17. Rxg6 fg 18. Nxe6, trapping Black’s queen.

However, post-game analysis revealed that in fact 16. … g6 is playable, and that is the move MVL played against Alekseenko. Of course, Alekseenko thought this was a blunder and played 17. Rxg6. Then MVL uncorked the move that he (or his computer) found after the Carlsen game: 17. … Rxc3!!

This is of course a standard resource for Black in the Sicilian Defense, but in this particular case the point is somewhat different from usual. First, Black wants to free up the square c8 for his queen. Even so, that doesn’t seem to be enough to save him. After 18. Qxc3 Black still can’t take the rook on g6, because 18. … fg? 19. Nxe6 discovers an attack on the Black rook on h8, in addition to attacking the Black queen on d8. After 19. … Bf6 20. Nxd8 Bxc3 21. Nxb7 White escapes with an extra pawn or two.

But we’re not done! After 18. Qxc3 Black has yet another zwischenzug: 18. … Na4!, forcing White’s queen away from the long diagonal. After 19. Qb3 now Black can take on g6: 19. … fg 20. Nxe6 Qc8 and at this point White’s best option is to take a draw by repetition with 21. Ng7+ Kf8 22. Ne6+ Ke8.

No one would have blamed Alekseenko if he had bailed out into a draw this way. But to his very great credit, after a 48-minute think (!) he decided to continue playing for a win.

It’s fascinating how the same position can have very different psychological content for the two players. Vachier-Lagrave is in his home preparation. He has gone over this position, most likely several times, with a computer, and he knows that every variation leads to a draw if both players find the best moves. It’s a huge psychological advantage, because if his opponent does something unexpected he knows that there should be a solution and he just has to find it.

On the other hand, Alekseenko was clearly not prepared for MVL’s move 17. … Rxc3, and he had to fly blind through this exceedingly complicated tactical position. I think it’s a testament to his courage that he chose to do so (instead of bailing out to a draw at the first opportunity) and it’s a testament to his chess skill that he in fact found all the right moves and managed to draw the game. While Vachier-Lagrave was merely solving puzzles that he already knew had an answer, Alekseenko was fighting for his life without knowing what would happen. One chessboard, two very different games!

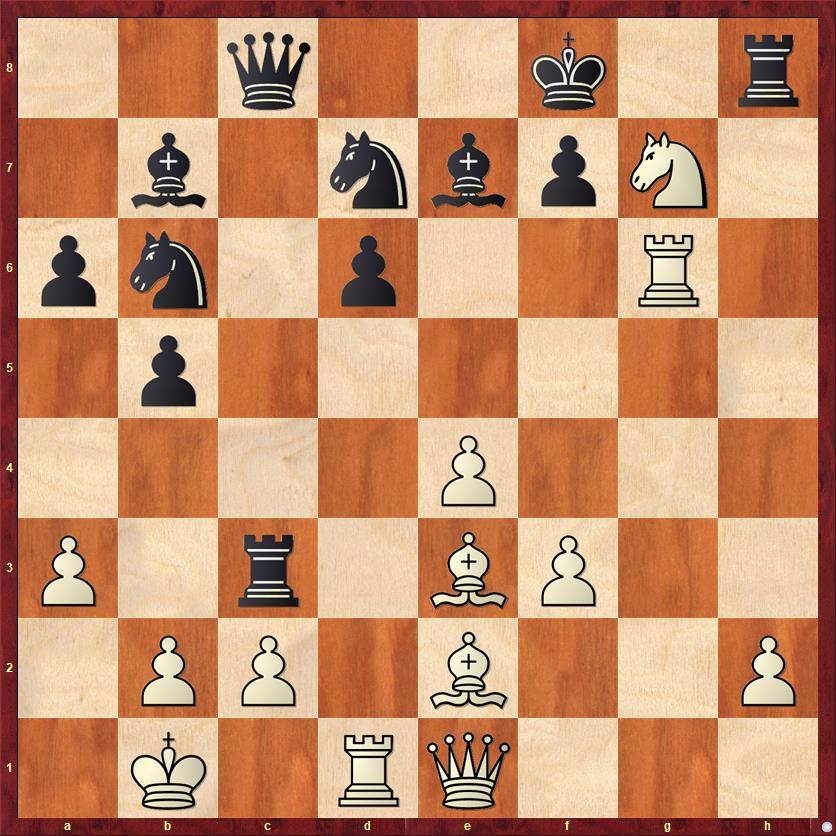

After his 48-minute think, Alekseenko doubled down with yet another sacrifice: 18. Nxe6! Obviously 18. … fe 19. Qxc3 would be bad for Black because the rook on h8 is attacked and the e-pawn falls. So MVL left everything en prise and played 18. … Qc8 19. Ng7+ Kf8. Now White has a rook hanging on g6, a bishop hanging on e3, and a rather insecure knight on g7. How can he save all of them?

FEN: 2q2k1r/1b1nbpN1/pn1p2R1/1p6/4P3/P1r1BP2/1PP1B2P/1K1RQ3 w – – 0 20

The answer is a very nice move: 20. Rh6! I always like this kind of move, when you protect one doomed piece with another doomed piece, thereby saving them both from extinction. If 19. … Kxg7? then 20. Qg3+ leads to mate. So Black has to play 20. … Rxh6, allowing White to save both the bishop on e3 and the knight on g7 with 21. Bxh6. Bravo!

After Vachier-Lagrave’s response, 21. … Rxc2, Alekseenko played his discovered check, 22. Nf5+ Ke8. There are lots of interesting options for White, like 23. Rxd6?! or 23. Bg5?!, but Alekseenko opted for the most straightforward move, which eliminates a good defender of Black’s king: 23. Nxe7 Kxe7 24. Qh4+ f6.

By the way, 24. … Nf6 also draws, provided that MVL is prepared to meet 25. Rxd6! not with 25. … Kxd6? but with 25. … Nbd7! White’s rook can continue its marauding ways with 26. Rxd7+! but after 26. … Kxd7 27. Qxf6 Rxe2 28. Qxf7+ Kc6 it’s clear that Black will not get mated as long as he keeps his king on light squares.

Great stuff! However, it’s understandable that MVL was a little bit wary of that line and played 24. … f6 instead. Alekseenko played 25. Bf4!, offering yet another piece sacrifice, his third of the game. Can Black take on e2? If not, how should he defend?

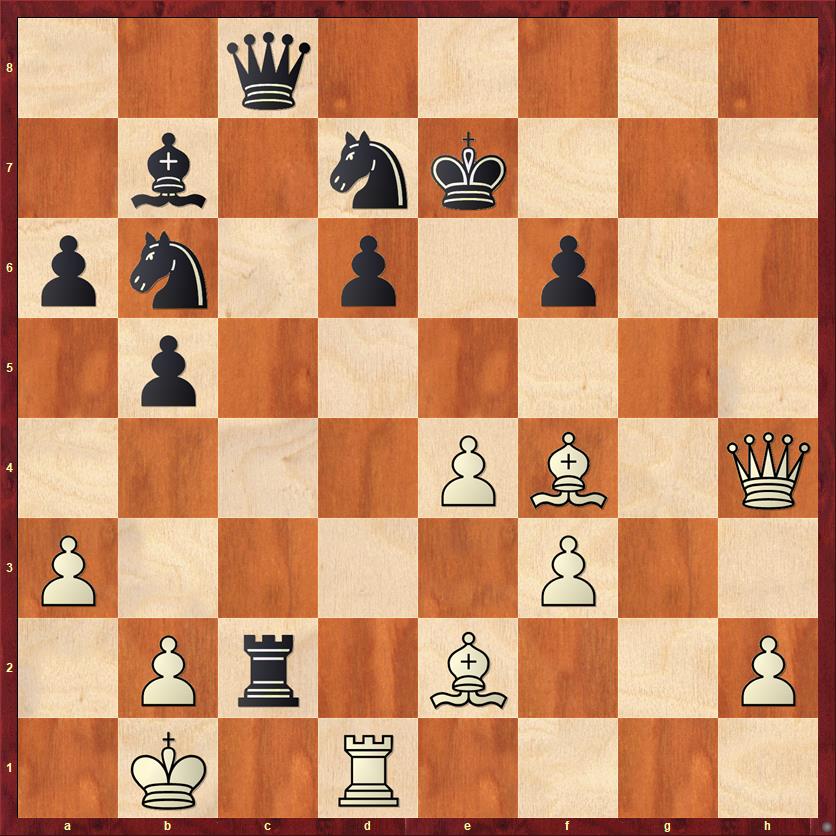

FEN: 2q5/1b1nk3/pn1p1p2/1p6/4PB1Q/P4P2/1Pr1B2P/1K1R4 b – – 0 25

First answer: 25. … Rxe2?? walks into a lovely mating net: 26. Bxd6+ Ke6 27. Qh3+! Kf7 28. Qh7+ Ke6 29. Qe7 mate! You don’t see that one every day.

If you’ve learned anything from this game, you’ve learned that the way to defend is to give away material, not take material. (Note: This is not true in all games, but definitely is in this one.) So MVL steers the clearest path to a draw: 25. … Rxb2+! 26. Kxb2 Na4+.

Unfortunately for Alekseenko, he has only one king move that doesn’t lose on the spot: 27. Kb1. After 27. … Nc3+ 28.Kh1 Nxd1both players headed for a draw by repetition. (Draw offers are not allowed before move 40 in this tournament.) 29. Qh7+ Kd8 (if 29. … Ke8 30. Qg6+) 30. Qg8+ Ke7 31. Qh7+ Kd8 32. Qg8+ Ke7 33. Qh7+ 1/2 – 1/2. The only remaining question is whether Alekseenko could have tried the endgame after 31. Qxc8 Bxc8 32. Bxd1 Ne5, but Black’s knight is such a strong piece that White didn’t see any point in continuing.

It’s funny that the annotation to this game on ChessBase says, “Not much happened in this game.” I’m pretty sure that statement was written by a computer! (Seriously, Fritz has an auto-annotate function.) More things happened in this game than in all of today’s other three games combined. I counted five piece sacrifices, three by White and two by Black, and lots more that could have happened. From a computer’s point of view, not much happened in this game because both players played the best moves. In fact, the computer gave Alekseenko an accuracy score of 100% for the game! That’s not a lack of action, that’s just great chess.

I feel sorry for those chess fans whom one might call Houdini/Stockfish Slaves, who don’t try to figure out the position for themselves and just follow the computer evaluations. From move 16 on, the computer evaluation was 0.00, so yes, “not much happened.” But for humans, this was a rich and fascinating game.

At the end of the day, here are the standings after five rounds (roughly one-third of the tournament).

1-1. Ian Nepomniachtchi, 3.5-1.5.

2. Maxime Vachier-Lagrave, 3-2.

3-5. Fabiano Caruana, Wang Hao, Alexander Grischuk, 2.5-1.5.

4-6. Ding Liren, Kirill Alekseenko, Anish Giri, 2-3.

Looking ahead, Robert Hess said on chess.com that Nepomniachtchi is a streaky player, who is not afraid to take risks. It will be interesting to see whether he starts playing it a little bit safer or whether he tries to stretch his lead (at the risk of going down in flames, the way Caruana did two rounds ago).