Yesterday’s chess party at Mike Splane’s house turned into an endgame workshop, because both Mike Arne and Paulo Santanna came prepared with some beautiful positions.

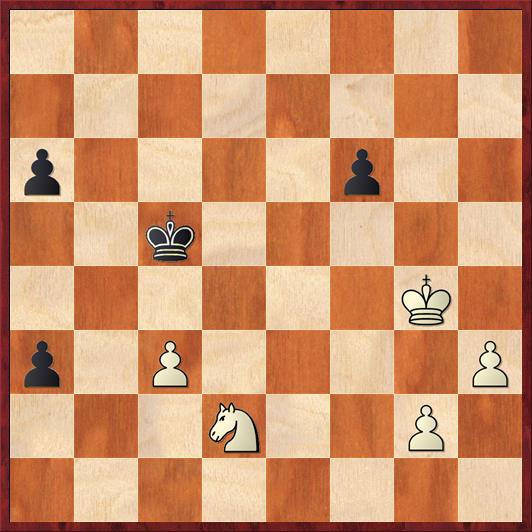

Ironically, both of them went to Spain this summer but they didn’t play in the same events. Mike Arne played in the Benasque tournament, and showed us this deceptively simple position.

FEN: 8/8/p4p2/2k5/6K1/p1P4P/3N2P1/8 b – – 0 1

Mike was playing Black, and it’s his move here. As Mike says, it’s obvious that Black’s next two moves are … a2 and … a5 in some order. The first move threatens to promote the pawn, but it’s not a real threat yet because of the defense Nb3+. The move … a5 is needed to put some teeth into Black’s threat; it forces White to play Nb3 right away, lest his knight lose the b3 square.

Mike didn’t think that the move order made any difference, so he played 1. … a2?? Astoundingly, this turns a won position into a lost position! But not a single person at the party saw White’s winning plan. And in fact, Mike’s opponent didn’t find the win either. He played 2. h4??, and after 2. … a5 Mike was once again on the winning track. The game finished 3. Nb3+ Kc4 4. Na1 (4. Nxa5+? is hopeless because after 4. … Kxc3 White’s knight cannot stop the remaining a-pawn) 4. … Kxc3 5. h5 Kb2 6. h6 Kxa1 7. h7 Kb1 8. h8Q a1Q. This has the makings of a very long endgame, but Black should be winning. The f6 pawn definitely helps Black escape from White’s checks. The game actually didn’t last too much longer because of a mistake from Mike’s opponent. 9. Qb8+ Kc2 10. Qc8+ Qc3 11. Qf5+ Kb7 12. Kh5? Qe5! Here White resigned. On the trade of queens, 13. Qxe5 fe, we once again get a pawn race where both sides queen, but this time Black queens first, plays … Qh1+ and … Qg1+, trades queens, and then promotes for the third (!) time with his remaining pawn.

Now let’s see where both players went wrong. After Mike’s mistaken first move, White should have played the ingenious 2. Kf3!! The idea is to bring the king one step closer to the queenside. He still seems hopelessly far away, but this sets up a “stalemate defense”. After 2. … a5 3. Nb3+ Kc4 4. Na1 Kxc3 5. Ke2 Kb2 6. Kd2 Kxa1 7. Kc2, we see the point of White’s idea: although Black has won the knight, he is unable to move the king out of the way of his own pawns. He is reduced to making pawn moves, and meanwhile White will promote the h-pawn. The cutest line is 7. … f5 8. h4 f4 9. h5 f3 10. h6 (White can simply ignore Black’s pawn!) fg 11. h7 g1Q 12. h8Q+ with mate next move.

In order to eliminate the “stalemate defense,” Mike should have played 1. … a5!! right away. Then White has to play 2. Nb3, and after 2. … Kc4 3. Na1 Kxc3 we transpose to the line actually played in the game, because White’s king is too far away to play the stalemate defense.

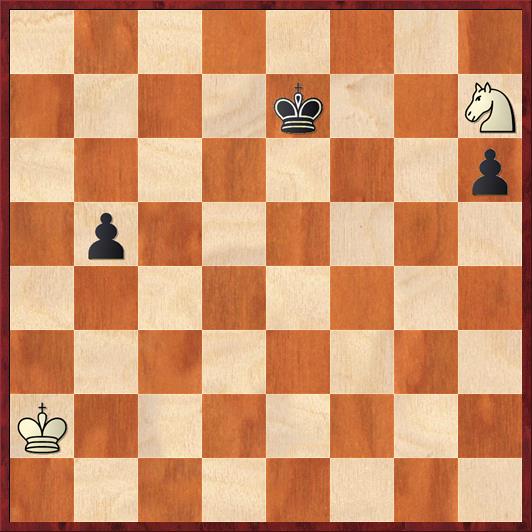

After Mike finished showing us this wonderful endgame, Paulo got up and showed us a similar study by Mark Dvoretsky, which has some of the same motifs of a knight trying to stop a rook pawn.

FEN: 8/4k2N/7p/1p6/8/8/K7/8 w – – 0 1

Again, just as in Mike Arne’s position, it seems as if there are two possibilities, 1. Kb3 and 1. Ka3, that are absolutely equivalent. The hard part once again is not finding the right move, but telling it apart from the wrong move!

Most people would play 1. Kb3??, just because it moves the king one square closer to the kingside. Because this is a Dvoretsky endgame study, you might suspect that this is wrong and 1. Ka3! is right instead. But do you see why?

The reason is that after 1. … Ke6!, White needs to extricate his knight in order to stop the h-pawn. Generally speaking, White can draw with the knight against the rook pawn if he can stop it before it reaches h2. Then the knight can hop around the “circuit” f1-h2-g4-e3 and can never be driven away.

The beauty and ingenuity of Dvoretsky’s study is that in this position White’s knight has to travel a much longer circuit, which goes h7-f8-d7-c5-b3 (The key square!! This is why 1. Kb3?? is a blunder.) and then d2-f1-h2. Thus the drawing line is:

2. Nf8 Kf5 (Black does his best to shut the knight out, but this turns out later to be an unfortunate square) 3. Nd7 h5 4. Nc5 h4 5. Nb3! (not Nd3, because the knight has to blockade the pawn on h1, and as we saw in Mike Arne’s game that doesn’t work, unless the king can help out with a stalemate defense) h3 6. Nd2 h2. It seems as if the knight has arrived too late, but Dvoretzky has one more trick: after 7. Nf1 h1Q 8. Ng3+! forks the king and queen. Amazing! Of course 7. .. h1N 8. Kb4 is also a draw.

Just going over these two endgames makes me feel as if I have gained 10 rating points. Certainly I understand the knight vs. RP scenario much better. It’s interesting to see how the right moves depend on concepts rather than I-do-this-he-does-that style analysis. The concepts are (1) the idea of a knight “circuit,” (2) the fact that a pawn on R7 is much harder to stop than a pawn on R6 because the knight gets trapped in the corner, (3) the possibility of the “stalemate defense,” and finally (4) the heroic “let him queen but then fork the king and queen at the last minute” defense.

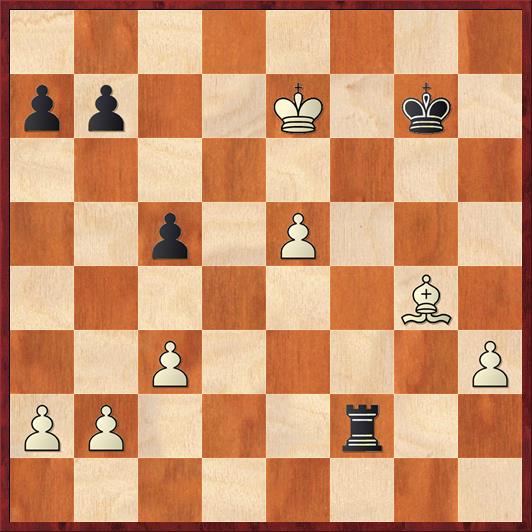

After this Mike showed us another endgame with a similar property – the correct moves depend on schematic thinking.

FEN: 8/pp2K1k1/8/2p1P3/6B1/2P4P/PP3r2/8 b – – 0 1

This was a game played by two Bay Area masters: FM Josiah Stearman (White) and IM Elliott Winslow (Black). Winslow played 1. … Rd2?, a sensible-looking move that tries to keep White’s king stuck in front of the pawn. But the trouble is that this is completely passive, and it doesn’t even work because White can play e6, Ke8, e7, Bd7, and Kd8 in some move order, just as in the game. The game ended up a draw (Mike didn’t show us how).

If Black wants to play for a win, he has to try 1. … Rxb2, with the idea of wiping out all of White’s queenside pawns and then sacrificing the rook for the e-pawn. Does this work?

As Mike pointed out, it all depends on whether the three connected passed pawns can beat White’s bishop all by themselves. He discovered a simple rule (actually, three of them):

- Is the RP the “wrong color”? In other words, is the queening square opposite to the bishop? The answer here is yes: White’s bishop cannot cover a1.

- Is the defending king too far away to help stop the pawns? Here the answer is yes, although just barely, as we’ll see.

- Can the pawns get to c4 and b5? If yes, then the pawns win, because they take away all the squares from which White’s bishop could stop the a-pawn.

So simple! Almost no analysis required. So in fact the following line would have won for Black: 1. … Rxb2 2. e6 Rxa2 3. Ke8 (unfortunately White has to lose a tempo this way, because 3. Kd8 would allow … Rd2+) 3. … Ra3 4. e7 Rxc3 5. Kd8 Re3! (… Rd3+ is unnecessary and would actually help White) 6. e8Q Rxe8 7. Kxe8 c4.

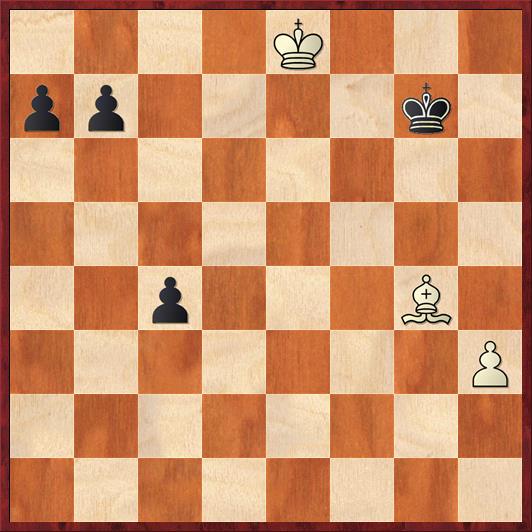

FEN: 4K3/pp4k1/8/8/2p3B1/7P/8/8 w – – 0 7

Black is aiming for the b5-c4 setup, and White can’t really stop it. For example, if 8. Bd7 c3 9. Ba4 b5! 10. Bc2 a5 and the pawn runs to a4 and a3. Once the pawns are on a3 and c3, they are unstoppable.

The trickiest variation in the position above is 8. Kd7. Here 8. … b5? is wrong, because 9. Kc6 gets the king into the defense in time. Instead Black recognizes that the pawn on b7 is doing good work, keeping White’s queen out of c6, and he plays instead 8. … a5! And the a-pawn is unstoppable, for example 9. Bd1 b5 10. Kc6 a4 11. Kxb5 a3.

Although this might seem like a rather special position, it addresses a very fundamental question: When do three pawns beat a bishop? Every chess player (above a certain level) knows the answer for rooks: two passed pawns on the sixth rank beat a rook. Yet I think most of us do not know the answer for bishops. From the above lines, a simple rule is: two passed pawns separated by a file on the sixth rank beat a bishop. (For example, pawns on a3 and c3 in the above lines.) If you have three connected passed pawns, they win if you can answer “yes” to all of questions 1-3, basically because you can then force a position where the pawns reach a3 and c3.

Note: I originally posted this entry with an incorrect position for the Dvoretsky study. (I had the king on a3 already!) My apologies to anyone who was confused.

Also, a followup to my last few posts: Teimour Radjabov won the World Cup, which is of some interest to U.S. chess fans because it means that Jeffery Xiong lost to the eventual tournament winner. Doesn’t change the fact that he lost, but maybe it’s a “moral victory.”

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Great column, thanks!

Just an FYI.

The rule of thumb I use most often in evaluating Bishop versus pawn endings, and in opposite color bishops endings as well, is very easy to apply and to remember. If the kings can not help to advance or to stop the pawns, the bishop can hold the position if it can reach a single diagonal that all of the pawns need to cross. If he has to guard 2 diagonals the pawns win.

With black pawns on a3 and c3 the bishop has to guard squares on two diagonals b1-a2 and ba-c3 or b3-a2 and b3-c2 When one pawn advances the bishop has to abandon one of the diagonals and allow the other pawn to queen.

Move the pawns one square up the board, a4 and c4, and the bishop can stop them on either the a3-c1 diagonal or the a3-c3 diagonal.

Adding a pawn doesn’t change the outcome, as long as it too can be stopped on the same diagonal. If Black pawns are on a4 b3 c2 the bishop can hold on the c1-a3 diagonal.

It works for widely separated pawns as well. For example, a bishop on f1 can stop black pawns on f2, d4, and b6.