The second week of the PRO Summer Chess League went a whole lot better for me, and a whole lot worse for the team.

Quick refresher: the summer league is an offshoot of the main (winter) league. One big difference is that fans can participate and score points for their favorite team. Each match consists of two parts: a team match in which fans of one team play two games against fans of another (as many fans as want to play); and a 4-man elimination tournament in which each team is represented by a single “pro” player (most likely a GM or IM).

Last week the San Francisco Mechanics got off to a pretty good start, beating the San Diego Surfers in the fan match, 20-12, while Daniel Naroditsky, our pro, placed second in the elimination tournament. This week we were paired against the Chengdu Pandas, and had a complete wipeout. We lost 34½ – 19½ in the fan match and finished fourth in the pro elimination tournament. We are not mathematically eliminated from playoff contention yet, but we will definitely have to beat St. Louis next week and get some good breaks to make the playoffs.

After my disaster last week, I was paired against a 1600 player named “attackchesskid.” In the first game I won a rook and was cruising to victory, but then managed to hang a rook in the only way possible. Disgusted and frustrated, I bailed out to a draw by repetition (which fortunately was there for the taking). I couldn’t believe that I couldn’t even win a game with an extra rook.

Under the circumstances, I was ecstatic to win my second game almost without thinking. The whole game lasted less than three minutes. I played a trap in the Center Counter Defense that I discovered a few years ago. It’s what Roman Dzindzichashvili calls a “good trap,” i.e., one in which you don’t make any dubious moves to set the trap. In this trap, you just play normal moves in an unusual order. If your opponent doesn’t fall into the trap, you can go into normal variations; if he does, then you have a winning attack. This was my first chance to try it in a game that actually meant something.

Dana Mackenzie – attackchesskid

1. e4 d5 2. ed Qxd5 3. Nc3 Qa5 4. Nf3 …

The hallmark of the trap I’m going to show you is that White delays the “normal” 4. d4 for several moves.

4. … Nf6 5. Bc4 Bf5 6. O-O e6 7. Re1 c6?

FEN: rn2kb1r/pp3ppp/2p1pn2/q4b2/2B5/2N2N2/PPPP1PPP/R1BQR1K1 w kq – 0 8

The great thing about this trap is that it absolutely does not look as if White is setting a trap. It just looks as if he is developing pieces and has gotten a little bit confused about the move order. I would expect the trap to be especially effective in speed chess or against “booked-up” players who prefer to play memorized moves – in other words, exactly the situation in this game.

In the normal book lines, 7. … c6 is the move Black typically plays. However, there is absolutely no reason for Black to play it here. Best is 7. … Nbd7, to prevent Re5. Then White has a choice between 8. d4, transposing into the normal variation, or 8. d3, which would force the players to think for themselves. I would have played 8. d3.

8. Re5! …

Seizing the opportunity created when Black played his memorized move.

8. … Qc7 9. Rxf5! …

The whole point of the variation. White sacrifices the exchange in order to win the pawn on f7 and chase Black’s king into the center of the board. I have not done a thorough analysis, but the computer gives White at least a 1-pawn advantage in all lines. From the practical point of view, the position is much easier for White to play – as we see in this game, where Black blunders almost immediately.

9. … ef 10. Ng5 Ng4

FEN: rn2kb1r/ppq2ppp/2p5/5pN1/2B3n1/2N5/PPPP1PPP/R1BQ2K1 w kq – 0 11

A good, feisty move. I would expect nothing else from a player named “attackchesskid.” Obviously White would like to avoid playing a purely defensive move like 11. g3. So there are two checks that come into consideration, 11. Bxf7+ or 11. Qe2+. Which one would you play?

11. Bxf7+?! …

The wrong check! I was surprised to see that Rybka significantly prefers the other move, 11. Qe2+. After sacrificing an exchange, why would White want to let Black trade queens?

There are two reasons. First, White would rather take on f7 with his knight than with his bishop. With the bishop on f7 and the knight on g5, both the knight and the bishop are vulnerable to attack, and the situation is rather precarious. The setup with the knight on f7 is much more stable. Also, the knight on f7 threatens to win more material – the rook on h8.

Second, after 11. Bxf7+ Ke7! 12. Qe2+ Qe5!, White is forced to trade queens anyway, and in a worse position than if he had played 11. Qe2+ right away (because he has the bishop on f7 rather than the knight).

Thus, best according to the computer is 11. Qe2+! A third point, which is quite crucial, is that White is completely winning after 11. … Be7? 12. Bxf7+ Kd7 13. Qd3+! This funky little move wins the f5 pawn with check followed by taking the knight on g4.

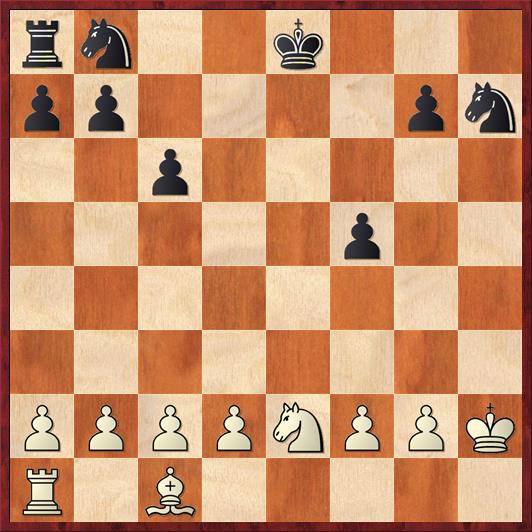

If Black instead answers 11. Qe2+! with Qe5, the followup is 12. Nxf7 Qxe2 13. Nxe2, when White has the “right” piece on f7. A typical line goes 13. … Rg8 14. Nd6+ Bxd6 15. Bxg8 Bxh2+ 16. Kh1 Nf6 17. Bxh7 Nxh7 18. Kxh2. (See diagram.)

This is a pretty amusing position! I’ve never seen a game where White, after 18 moves, has not moved a single piece or pawn past the second rank! Nevertheless, the extra pawn, lack of weaknesses, and bishop-versus-knight advantage give White an excellent chance of winning the endgame.

In our game, Black chose the worst square to move his king to:

11. … Kd8?? 12. Ne6+ Kd7 13. Nxc7 Kxc7

With a queen for a rook White is easily winning. There was just one more odd thing that happened.

14. d4 Bd6 15. h3 Nf6 16. Bf4?? …

Augh! Mouse slip! One more thing I hate about online chess.

16. … Nbd7??

What?! My guess is that Black played this as a “pre-move,” which means he couldn’t take it back and capture the free piece that I offered him. Yet another way in which online chess bears no resemblance to real chess.

The rest of the game needs no comment.

17. Bxd6+ Kxd6 18. Qf3 g6 19. Qf4+ Ke7 20. Bb3 Rhe8 21. Re1+ Kf8 22. Qh6 mate.

An imperfect game, but at least it finally gave me my first win in an active-chess game on chess.com after two terrible losses and a terrible draw. Now maybe I can relax a little bit next week.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I once won a game where I only spent about five minutes, and my opponent almost dropped the flag after spending his hour and a half. And it wasn’t even a trap or something, it’s actually just one of my best games:

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Nf6 5. Nxf6+ gxf6 6. Nf3 Bf5 7.

c3 Nd7 8. Bf4 Nb6 9. Be2 e6 10. Nh4 Bg6 11. Nxg6 hxg6 12. Bd3 Bd6 13.

Bxd6 Qxd6 14. Qf3 Nd5 15. g3 O-O-O 16. O-O-O f5 17. Qe2 Rh3 18. f4 Rdh8

19. Rdf1 Nf6 20. Rf2 Qd5 21. Qf3 Qxa2 22. Bf1 Ng4 23. Rd2 Rxh2 24.

Rhxh2 Nxh2 25. Qh1 Qa1+ 26. Kc2 Qxf1 27. Qg2 Qxg2 28. Rxg2 Nf3 29. Kd1

Rh2 30. Rxh2 Nxh2 0-1

There are few things more annoying in chess than getting to play your favorite line/home analysis, and then botching it up! I’ve done this before on several occasions, kicking myself for not having gone that one extra move deep, or not having reviewed my analysis recently enough to be able to recall what’s going on.

After having seen on your blog what you have referred to as the “The Zvedeniouk-Mackenzie Trap”, I have incorporated it into my repertoire as an option against the Scandinavian. I haven’t had a chance to play it yet, but…

My notes follow your analysis all the way up to 16 Kh1. There, instead of 16 … Nf6, my computer had suggested the kind of weird 16 … h5, so that’s what I had plugged into my “analysis.” I also have entries for the other two alternatives for Black on move 8, namely 8 … Qd8 (which still allows 9 Rxf5!) and the superior but hard-to-find-over-the-board 8 … Qb4!