This weekend I’m in Reno to play in my second chess tournament of the year, the Western States Open. When I got up this morning I wanted to wash my hair, but I couldn’t find the complimentary bottle of shampoo provided by the hotel. I looked high, I looked low, I looked in the bathroom, I looked in the bedroom — nothing.

Then, completely by accident, I looked in the mirror, and I saw it immediately! Somehow it had been wrapped up in a washcloth in just such a way that I couldn’t recognize it from the front, but immediately recognized it from the back.

Chess provides a lot of situations similar to my parable of the shampoo and the mirror. Sometimes we find ourselves in positions where the right move seems very hard to find — until we ask ourselves the right question, and then the answer becomes obvious. By asking the right question, we can find the right move even if part of our analysis is faulty (“I can’t find the shampoo anywhere!”). Sometimes a shift in perspective is all that y0u need.

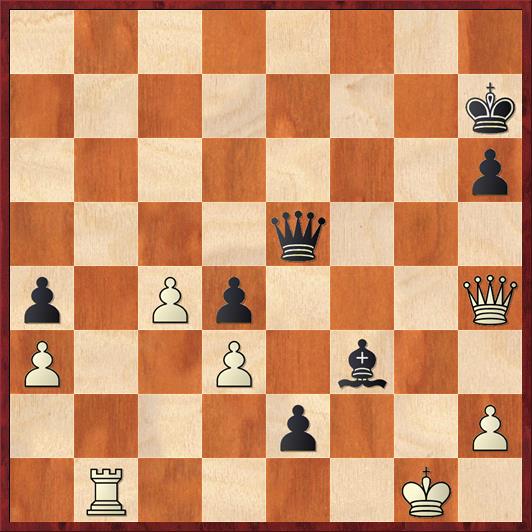

Here’s a game I played against the computer this week that illustrates these ideas. I’m playing Black, and Shredder (set at a strength of 2412) is playing White. Against the computer I allow myself one time-out per game, and I took it in this position.

Position after 38. Nf4. Black to move.

FEN:q4r2/1b2N2k/1R5p/8/p1Pp1N2/P2PpnP1/7P/3Q3K b – – 0 38

Ironically, if you give this position to a computer and ask it for Black’s best move, you will be told that it doesn’t matter. Black can play 38. … Rxf4 or he can play any discovered check with the knight — they all evaluate as 0.00, a draw. But to me, it was not obvious that Black can draw in all variations: What if White’s king tries to run to g3 or h3? You could spend hours trying to work out all the possibilities.

That, I would argue, would be the analogue of my looking high and looking low for the shampoo. First, we need to look in the mirror and ask ourselves a version of the Mike Splane Question: Am I playing for a draw or am I playing for a win?

The answer is, of course, I’m playing for a win! Granted, Black is a pawn down, but there are three ingredients in the position that are hugely in my favor. First, I have a very menacing attack against a king that is nearly in a mating net and is very inadequately defended. White’s rook and knights are very far away, and if they can be prevented from participating in the defense (by N7d5, N4d5, or Rxb7) then White’s only defender will be the queen. Second, I have a passed pawn at e3 that is much more dangerous than White’s passer on c4. In many variations Black’s winning plan is simply to play … e2 and … e1Q. Again, White’s pieces (other than the queen) are in no position to stop this. Third, White has a number of loose pieces — the rook on b6, the knight on e7 — and “loose pieces drop off.” In some cases I can gain time by attacking one of them; in other cases I can simply win one of them.

So the answer to the Mike Splane Question, “How am I going to win this game?” has to be as follows: 1) prevent N(either) to d5 or Rxb7; 2) place the bishop on f3 as soon as possible, so that none of the above moves becomes a problem in the future; 3) possibly sac the rook on f4 to eliminate a defender; and 4) Win with either … Qg2 mate or … e2-e1Q or simply by snatching a loose White piece.

How does this guide us toward finding the right move? Well, first, 38. … Rxf4 is eliminated because it makes White’s defense too easy. After 39. gf Nd2+ (or any knight check) White can sac the exchange back with 40. Rxb7 and blunt Black’s attack. If we’re playing for a win, this is not the way to go. Moral: Don’t sacrifice material until you need to!

Second, of the many knight checks, the ideal one would threaten g2 and not get in the way of our intended … e3-e2-e1 advance. This rules out the otherwise attractive move 38. … Nd2+, because we can no longer play … e2 because the knight hangs. Another good general principle here is that when attacking, you should play the moves that give yourself the greatest flexibility. If we sabotage ourselves by taking away the … e3-e2-e1 threat, we give our opponent fewer threats to worry about.

So the move that stands out as being most consistent with our plan is 38. … Nh4+. And we figured this out without doing any analysis! Furthermore, when we start looking at variations it seems as if this move also prevents White from getting any of his minor pieces involved in the defense. 39. Rxb7 gives up the exchange, and Black should be better. Notice the benefit of not sacrificing on f4 until you have to! On the other hand, if 39. N7d5 now 39. … Rxf4! is a stone-cold killer: 40. gf Bxd5+ obviously leads to mate, and 40. Rxb7+ Qxb7 41. gf gives Black an absolutely exquisite win after 41. … e2!! 42. Qe1 Qb3. These variations beautifully illustrate what Black can do by combining the mating threats with the pawn-promotion threats. Finally, 39. N4d5 seems to lose to 39. … Rf2 (see diagram).

Position after 39. … Rf2 (analysis). White to move.

FEN: q7/1b2N2k/1R5p/3N4/p1Pp3n/P2Pp1P1/5r1P/3Q3K w – – 0 40

Here I made a mistake in my analysis! Of course, Black’s threat is … Nf3 (a new winning idea!), so White has to play 40. gf. But then 40. … e2 seemed crushing to me, and I stopped my analysis here. But I was wrong! In fact, 40. … e2 is a mistake because it allows 41. Qd2!, threatening Qxh6+! All of a sudden Black has to worry about White’s counterattack. But wait a minute, you may say. Can’t Black just play 41. … Bxd5+ 42. cd (not 42. Nxd5?, when 42. … Rf1+! 43. Kg2 Qg8+ wins) 42. … Qf8? This defends h6 and seems to create unstoppable threats on the back rank. But again, looks are deceiving! White can throw a monkey wrench into Black’s plans with 43. Nf5!! If Black takes with the queen, White wins with Qxh6+. If Black takes with the rook, White wins the e2 pawn and now Black will have to fight for a draw.

So in fact, after 40. gf in the diagrammed position Black should play 40. … Qf8 first, anticipating White’s threat. After several very difficult “only moves” for both sides, the game ends up being a draw. I will leave the analysis to you — it’s quite spectacular!

During my time-out I didn’t see any of this stuff, and I just thought the diagrammed position was winning. It was the computer (Rybka) that found White’s miraculous drawing line. Nevertheless, I would argue that my move 38. … Nh4! was exactly the right move! Even if I had possessed Rybka’s perfect vision and realized that White could draw, it would still be much better to play a variation where White draws only by a miracle than to play a variation where White draws easily. This is where the computer fails: to it, a draw is a draw. It has no conception of “drawing by a miracle.” But I can tell you that somewhere around 0.01 percent of human players would have found the drawing line for White. So I got to the right answer even though my analysis was slightly flawed.

Remarkably, even my computer opponent (Shredder) did not find the drawing line, perhaps because it was set at 2412 strength rather than its maximum strength of 2600. Going back to our original position, after my move 38. … Nh4+! it played 39. Kg1? and now Black is winning! To avoid confusion, the position is diagrammed below.

Position after 39. Kg1. Black to move.

FEN: q4r2/1b2N2k/1R5p/8/p1Pp1N1n/P2Pp1P1/7P/3Q2K1 b – – 0 39

Black’s next move should not be hard for you to find, because I already told you my answer to the Mike Splane Question, “How am I going to win this game?”

39. … Bf3!

Here White has six different plausible moves, and I wasted oodles of time during my time-out analyzing all six of them. It was incredibly fun, but during a tournament game I would not have that luxury. Here, in fact, I would argue that my thinking process was more seriously flawed than on the previous move. Instead of going through every line looking for a win (looking for the shampoo) I should look in the mirror and ask, what is Black’s biggest threat? In fact, on every queen move except 40. Qe1, Black wins with 40. … Rxf4! A pretty example is 40. Qc2 Rxf4! 41. gf Bd1!! 42. Qb2 e2! Once again we see the power of combining the mate threats on g2 with the pawn-promotion threats.

The only move that needs to be treated differently is 40. Qe1, because now after 40. … Rxf4? 41. gf the knight on h4 is hanging. But it’s easy enough to work out that Black wins after either 40. Qe1 Ng2 or 40. Qe1 Bh5 (the move I was going to play).

In fact, Shredder played 40. Qf1, and I played my standard winning move, 40. … Rxf4! But then, after 41. gf, I made an interesting mistake. I realized that I needed to move my queen to the kingside, and I realized that attacking White’s loose knight on e7 would give me an extra tempo to make the transfer. (Remember point three of the winning plan!) However, for some reason I got hypnotized by the move 41. … Qf8?!, which makes the win a lot harder. After 41. … Qe8 42. Re6 Qh5 White’s defenses crumble.

But there’s actually a good reason that I got hypnotized, because after 41. … Qf8 there are some spectacular tactics. If White doesn’t want to lose material he has to play (and did play) 42. Ng6! At first this looks like a gut shot, but I had an answer up my sleeve: 42. … Qf5! Now White’s intended move 43. Nxh4? fails to 43. … Qg4+ 44. Ng2 e2! 45. Qf2 e1Q+! For the umpteenth time, we see how the combination of two threats, the mate on g2 and the pawn promotion, is too much for White to defend. Also, 43. h3? (to prevent … Qg4+) fails to 43. … e2 (chasing the queen away from the defense of h3).

However, here too White has a stunning defense: 43. Ne5!, which keeps the queen away from any of the checking squares on the e-file. But of course, I anticipated this too (remember, I told you I spent a long time analyzing the position during my time-out), and I played 43. … e2! 44. Qf2 Qxf4. The tempo gained with 43. … e2 was crucial, because now White does not have time to exchange on f3. He is forced to play (and, in fact, did play) 45. Rb1 to defend the back rank. The next two moves are fairly obvious: 45. … Qxe5 46. Qh4. But Black’s next move is far from obvious, and it was in fact my favorite move of the whole game. (See diagram.)

Position after 46. Qxh4. Black to move.

FEN: 8/7k/7p/4q3/p1Pp3Q/P2P1b2/4p2P/1R4K1 b – – 0 46

At first, Black’s move seems absolutely obvious: of course I should play 46. … Qe3+ 47. Qf2 Qxd3, right? I mean, what could go wrong?

Well, what could go wrong is 48. Rb7+!! If Black takes the rook, 48. … Bxb7, then 49. Qf7+ is an instant draw by repetition. And if Black tries to escape the rook checks, then the instant he steps on the g-file White will play Qg3+ and have a winning attack.

This is the same sort of “miraculous draw” that I missed earlier, but I’m happy to say that I spotted this one. So in the above-diagrammed position, I asked, is there anything that I could do before playing … Qe3+ that would eliminate White’s miraculous draw?

And after a little thought, it hit me: Black can play 46. … h5!! I’d give this three exclaims if I could. Rybka confirms that it is the only winning move. The point is simply that Black is creating an extra flight square on h6 for the king. Thus, for example, if 47. Qf2 Qb5+ 48. Qg3 Qe3+ 49. Qf2 Qxd3 50. Rb7+ Bxb7 51. Qf7+ Kh6! 52. Qf6+ Black now has the winning get-out-of-check-with-a-check move, 52. … Qg6+! White does have other checks besides Qf6+, but it’s pretty clear that on Qf4+ or Qf8+ Black can head his king over to the queenside and eventually escape the checks.

This shows the importance of anticipating the opponent’s tactics. Moves like 46. … h5!! are when chess is really worth all the struggle.

Instead Shredder played 47. Re1, but now Black is definitely winning after 47. … Qe3+ 48. Qf2 Qxd3. This was the point at which I stopped my analysis during the time-out. So you can see that my move 41. … Qf8 was not really a mistake, because I had worked it out to a winning position. However, there’s no question that 41. … Qe8 would have been easier, and would be preferable in an actual tournament game.

The rest of the game does not require too much comment. It went 49. h4 Qe4 50. Kh2 d3 51. Qa7+ Qb7 52. Qd4 Qc7+ 53. Kh3 Bg4+ 54. Kg2 Qc6+ 55. Kg1 Qf3 56. Qe5 Be6! This was the last really nice subtlety of the game, and I had to find it over-the-board because we’ve long since left my time-out analysis. After 57. Qg5 Qg4+ 58. Qxg4 Bxg4 59. Rxe2 de nothing more needs to be said. Except I’ll say something anyway! I was interested to see that for 17 out of 18 moves after my so-called “mistake” on move 41, I played the top move according to Rybka. The only exception was move 51, where Rybka slightly prefers 51. … Kg6 instead of decentralizing the queen with 51. … Qb7. But the difference is really academic; +4.28 pawns for Black versus +3.87 or something like that. I would like to think that from move 41 on, I played the game perfectly.

Okay, time to re-focus my attention on the upcoming tournament, instead of the practice game from several days ago.