Once upon a time there were two guys who liked to play chess in a park. One of them worked for a tech company, and the other had an idea. Why not build a chess website that would be both a hangout and a database? They didn’t really have a plan for making money, but it didn’t seem to matter. This was 2000, during the first dot-com boom, an era when it seemed as if anybody could set up a website and the world would come to it.

And so Chessgames.com opened its (virtual) doors in 2001, and lo, the chess world came. The membership grew to more than 200,000. The number of games in the database grew to more than 700,000. Everything was wonderful. Then one of the co-founders died.

But it was still okay, because the other co-founder, the tech guy was still alive and young and kept the website running with its own unique flavor that mixed chess geekdom with Reddit-style no-holds-barred user commentary. If you didn’t want to spend money on a database program, Chessgames.com was the premier free solution.

But then, completely out of the blue, the other co-founder, Daniel Freeman, died just two months ago at a mere 50 years of age. And now there are real questions surrounding the future of what has been for years one of the go-to chess websites.

First, let me say that I never knew Daniel Freeman, never had any contact with him except through visiting the website and appreciating his handiwork. However, the tributes that poured into the website in the days after his death all testified to the fact that he was a gentleman who treated every visitor who had a question as if that person was the only visitor to his website. If you submitted your game to Chessgames, you got a personal answer from Freeman. Even the trolls and flame-war lovers, of whom there were quite a few, didn’t seem to mind too much when Freeman told them they had gone too far. He was one of the most tolerant webmasters around, so if he said you had gone too far, you probably had.

In the aftermath of Freeman’s sudden death on July 24, a long-time user and friend who goes by the user name of Sargon (no one, not even Wikipedia, seems to know his real name) posted that he was going to keep the site running. He candidly admitted that he did not know all the ins and outs of the administrative software, but he knows enough. To those who say that the sky is falling in, he has said, “Don’t panic.” Chessgames may be running behind in posting new games, and some other things may be glitchy, and the trolls may be running wild, but the site is not going anywhere.

Still, one does have to worry a little bit. The ownership of the site is not clear, at least from the outside. The legal ramifications of a death can take a while to work themselves out. And even if it had happened in a less traumatic way, this kind of transition is exactly the problem with a one-man show, which describes a lot of Internet businesses.

I used to work for a nearly one-man show, ChessLecture.com. It ran great for a few years, but inevitably the pressure wore down the guy who was running it, and we went through a similar Perilous Transition. New owners were found who kept the website running and who have improved it in various small ways. But it was a difficult time and I think that it permanently impacted the site’s membership base. That and the fact that so many other sites, like chess.com and YouTube, have lessons that you can view for free.

My experience makes me think that the long-term solution for Chessgames.com cannot be simply transitioning to another one-man show. Whoever he is, “Sargon” will eventually run out of energy and/or enthusiasm, and probably faster than Freeman did. I hope that Chessgames will find a more sustainable business model, and a larger and more stable ownership. Frankly, this seems to me like something that either the USCF or Rex Sinquefield ought to support, because it provides such a huge service to the chess community.

Freeman, a 1700-level player, included seven games of his own on the Chessgames database. Although the database is supposed to consist mostly of master games, I don’t think that anyone would begrudge him this small bit of self-indulgence. One of the seven games is particularly notable, because of who his opponent was. And it was quite an exciting battle, which teaches an important lesson.

Daniel Freeman (1726) — Ray Robson (1972)

U.S. Open 2004

When this game was played, Robson was nine years old!

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Bg5 Be7 5. e3 O-O 6. Qc2 h6 7. h4 …

Of course, White is begging Black to take the bishop and open the h-file for him. But Black doesn’t have to take the bait, and it is open to debate whether this move is creating a long-term weakness or serving as the launching pad for a kingside attack. White is committed now to castling queenside, which as this game shows is a risky choice in a queen pawn opening.

7. … b6 8. cd ed 9. Bd3 Be6 10. Nf3 c5 11. Bxf6 Bxf6 12. O-O-O Qc8 13. Ng5?! …

This move looks a bit like an amateur’s move to me, although the computer does not suggest anything much better. White is again playing “hope chess,” hoping that Black will take the knight and kick-start White’s attack. On the plus side, White is trying to put pressure on his opponent, and one has to commend Freeman for that. But meanwhile, the knight has moved away from the center, causing the d4-pawn to become especially weak. Robson wastes no time in taking advantage of that fact.

13. … Nc6

Rybka thinks that taking on d4 right away is slightly better, but this move cannot be wrong.

Now White’s “hope chess” really goes into overdrive.

Position after 13. … Nc6. White to move.

FEN: r1q2rk1/p4pp1/1pn1bb1p/2pp2N1/3P3P/2NBP3/PPQ2PP1/2KR3R w – – 0 14

Here the computer and I agree that White’s best try would be 14. Nh7. This move at least creates some kind of tangible result of the knight sortie. After, say, 14. … Nb4 15. Nxf6+ gf 16. Qb1 c4 White’s position is congested, but at least he has compromised Black’s pawn structure on the kingside, so there are chances for both sides. (Rybka says it’s equal.)

But Freeman played the shocking piece sacrifice 14. Nxd5?

What was he thinking about? Fortunately, he has told us his thoughts: “Yes, 14. Nxd5? was an error, but it wasn’t a mindless error. I became engrossed with the variation 14. Nxd5 Bxd5? 15. Ba6! winning the queen. However, I also found that the intermezzo 14. … Bxg5! seemed to refute my idea, although I had a vague feeling that it still might leave me with an attack.

At that point, I committed a cardinal sin of chess: I bluffed. I had fallen in love with my conception so much that I decided to play it anyhow, hoping that my young opponent wouldn’t be savvy enough to find the best defense. Bluffing is for poker, not chess.”

Well said! I especially like the part about not falling in love with your own ideas. This is a very important point on the road to chess mastery. For every tactical trick that a chess master plays, he sees at least two more that don’t work. To be a master, you have to be stone cold sober in your assessments. If it doesn’t work, you don’t play it, period. But also masters are very adept at keeping these ideas alive as possibilities, which might become playable one move or five moves down the road.

It goes without saying that I also agree with Freeman about bluffing. Every now and then a bluff might work, but usually it will not. You will lose more than you win, and your understanding of chess will not improve, because you took the easy way out (the bluff) instead of doing the hard work of figuring out what is actually the best move.

There are times when you honestly cannot tell whether a sacrifice is sound or not, and there are times when you might rely on the fact that it’s harder to defend than attack. This kind of bluff is perfectly okay. Often your opponents won’t take the material, because they have learned the same lessons too. But playing a move after you have seen what is wrong with it is definitely a recipe for disaster. It should be done only if you are in a completely lost position anyway. (If you can see refutations to all your moves, it becomes a matter of deciding which refutation will be hardest for the opponent to find.)

Robson, a future grandmaster, of course does not fall for Freeman’s bluff, and tears into his position with great gusto.

14. … Bxg5! 15. hg Bxd5 16. gh Nb4 17. Bh7+ Kh8 18. hg+ Kxg7

At least White has succeeded in opening the h-file. Not time to give up yet.

19. Qe2 cd+ 20. Kb1 Bxa2+ 21. Ka1 Bc4!

Giving the queen a route into the attack.

22. Qh5 Qa6+ 23. Kb1 Ba2+

And now, curiously enough, we have arrived at exactly the kind of position I was just talking about. Both of White’s king moves lose, but which one makes it hardest for Black to finish the game?

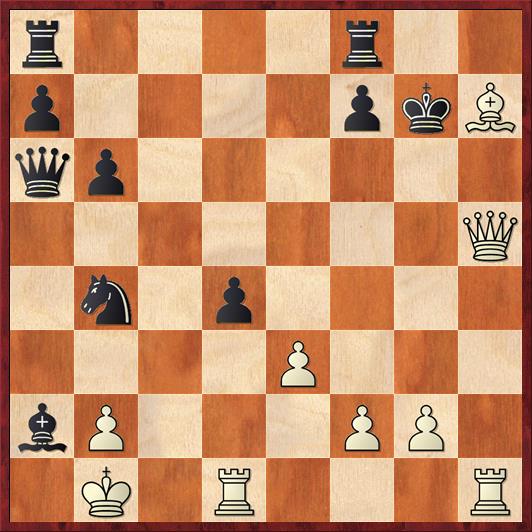

Position after 23. … Ba2+. White to move.

FEN: r4r2/p4pkB/qp6/7Q/1n1p4/4P3/bP3PP1/1K1R3R w – – 0 24

Here, if I were playing White, I would have played 24. Ka1. This counterintuitive move, walking back into the lion’s den, of course loses. But the point is that Black cannot win just by playing checks. He does not have a mating net. (That bishop on h7, in fact, does a great job of defense; Black can never play a move like Nd3+ or Nc2+ because the bishop takes it and then Black’s king is in a mating net.)

The problem for Black is that if he can’t checkmate White directly, or at least trade off either the queen or the rook at h1, then Black will have to play at least one move of defense. Here is what happens if Black goes for Maximal Attack With No Defense: 24. Ka1!? Bb3+ 25. Kb1 Qa2+ 26. Kc1 Rac8+? (26. … Rfc8+ is better, creating luft for the king) 27. Kd2 de+ 28. Kxe3! Rfe8+ 29. Kf4!! and Black has no way to checkmate and no good way to prevent Qh6+. According to Rybka, his only choice is 29. … Qxb2 30. Qh6+ = with perpetual check. I could totally see many players falling into this, although maybe not Robson.

Instead the silicon monster says that Black should play 24. Ka1 Bb3+ 25. Kb1 Qa2+ 26. Kc1 Rfc8+! 27. Kd2 Qxb2+ 28. Ke1 Kf8! Black’s king runs away and, supposedly, White can’t catch him. But if I’m White, I’m totally fine with this variation. If I can force Black to play some defensive moves, then I still have a chance. Even if I lose, it will be an honorable defeat.

Instead Freeman played the more natural 24. Kc1?!, which allows the young prodigy to win without ever breaking a sweat.

24. … Qc4+! 25. Kd2 de+ 26. Kxe3 Rfe8+ 27. Kf3 …

Note that in this variation, Kf4 is not possible.

27. … Qe2+ 28. Kg3 Qxh5

Mission accomplished. The attack is defused, and Black’s extra piece will win easily. Freeman played one more move, 29. Rxh5, but then he either resigned or lost on time.

Lessons:

- Don’t fall in love with your own ideas.

- Don’t play “hope chess.”

- Don’t bluff. (This is another form of hope chess.)

- But if you’re in a lost position, do play the move that gives your opponent the greatest chance to go wrong.