This morning I got a reminder in Facebook of a blog post I wrote exactly two years ago, called How to Beat a Grandmaster. My friend Robin Cunningham, a FIDE Master, was at that moment playing in the Hastings Masters tournament in England, which traditionally bridges the old year and the new year in chess. Robin got off to a great start that year, with a very impressive win in round one against GM Glenn Flear that was the subject of my blog post, followed by a draw in round two against GM Daniel Gormally. Robin finished with a score of 5/9, including a 2/6 score in his six games against grandmasters.

Robin isn’t playing at Hastings this year — in fact only one American player is — but history is nevertheless repeating itself. In round one a young British FIDE Master named Adam Taylor (rating 2242) defeated the highest-rated player in the tournament, Deep Sengupta of India (2586) on board one. And like Robin, Taylor has followed up his strong start by drawing against another grandmaster (Alexander Cherniaev) with the Black pieces in round two. Can Taylor keep the pace going?

At this point, though, the similarities end. The two games are quite different. Robin’s was complicated and hard-fought, and it includes a brave queen sacrifice. Taylor’s victory, on the other hand, was simple and pure. His opponent made a mistake in the opening, in a variation that looks a little bit suspect to me. Taylor then initiates a series of what seem to be harmless exchanges, but at the end of the exchanges it turns out that one of Sengupta’s pieces has nowhere to go!

If you don’t believe that a grandmaster can reach a lost position in ten moves against a FIDE master, this game will prove it to you.

Adam Taylor (2242) — Deep Sengupta (2586)

1. Nf3 d5 2. g3 Nf6 3. Bg2 Bg4

This move has been played many times, but I have to query what the point of it is. Why not just put the bishop on f5 right away? What is the point of giving White a free tempo for 4. Ne5? I’m sure these questions have reasonable answers, but Sengupta completely fails to answer them in this game.

4. Ne5 Bf5 5. c4 c6 6. cd cd

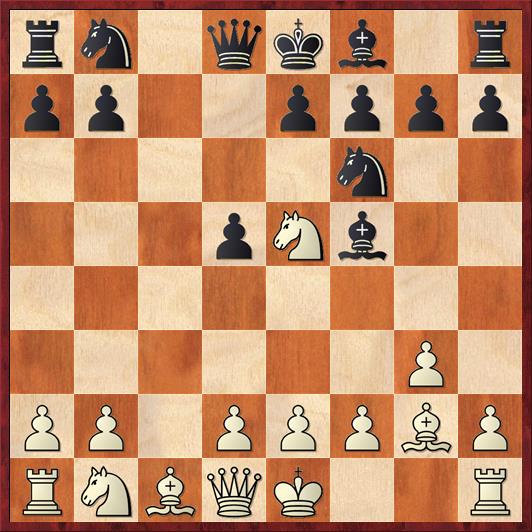

Position after 6. … cd. White to move.

Position after 6. … cd. White to move.

FEN: rn1qkb1r/pp2pppp/5n2/3pNb2/8/6P1/PP1PPPBP/RNBQK2R w KQkq – 0 7

Here White already has an interesting option of playing 7. Nc3, adding to the pressure on Black’s center. The main point of this is that 7. … d4? would be met by 8. Qb3!, threatening mate on f7 as well as adding another attacker to the pawn on b7. In ChessBase Black’s two most common replies to 7. Nc3 are 7. … e6 and 7. … Nc6. However, each one of these has liabilities. After 7. … e6 White can play 8. g4! when the pawn cannot be taken because White trades a pair of pieces and then plays the fork Qa4+. So Black has to play 8. … Bg6 and then White continues 9. h4, and if Black plays 9. … h6 White can seriously compromise his pawn structure with 10. Nxg6. As for 7. Nc3 Nc6, 8. Nxc6 compromises Black’s pawn structure on the queenside, giving Black a rather weak pawn on c6.

These lines already convince me that there is something not quite right with Black’s position, and I have to go back to 3. … Bg4 as the source of the problems.

Taylor opts for a slower, safer approach, but as the game shows this approach too poses real problems to Black.

7. O-O e6 8. d3 Bd6?!

According to Rybka, this is where Black really gets into trouble. More flexible is 8. … Nbd7, so that Black can answer 9. Qa4 with 9. … a6. This game is a good example of why they always tell you to develop knights before bishops.

9. Qa4+ Nbd7 10. Bf4 Qe7?

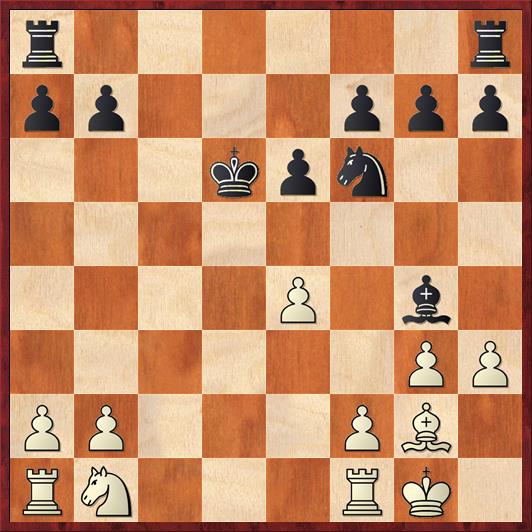

Position after 10. … Qe7. White to move.

Position after 10. … Qe7. White to move.

FEN: r3k2r/pp1nqppp/3bpn2/3pNb2/Q4B2/3P2P1/PP2PPBP/RN3RK1 w kq – 0 11

White to play and beat a grandmaster for the first time in his life!

The position after 10. Bf4 had occurred only once before in ChessBase, so there is no way that this was home preparation by Taylor. In the previous game, Black sniffed out the danger and played 10. … Bxe5, which is probably the “least-worst” move. However, in this game, Black is probably overconfident because he is a GM playing an FM, and he is oblivious to the danger.

It’s hard to blame him, because all of Black’s developing moves seem to be pretty natural. However, notice how all of Black’s pieces form a clump in the center. Positions where all the pieces form a clump often are worse than they look, and that is certainly the case here.

11. e4! …

A natural break that is made much stronger by the fact that there are so many pieces that White’s advancing pawns can attack.

11. … de 12. de Bg4

This is essential, in part because it controls the d1 square but more simply because 12. … Bg6? would lose to 13. Nxg6 hg 14. e5.

13. Nxd7 Qxd7

13. … Nxd7 would fail catastrophically because of 14. Bxd6 Qxd6 15. e5!

14. Qxd7+ Kxd7

Maybe Black thought he was safe here because White can’t play 15. Rd1. However, he underestimated the power of simple exchanges.

15. Bxd6 Kxd6 16. h3! …

Position after 16. h3. Black to move.

Position after 16. h3. Black to move.

FEN: r6r/pp3ppp/3kpn2/8/4P1b1/6PP/PP3PB1/RN3RK1 b – – 0 16

And suddenly it becomes obvious that Black is completely busted. He has no way to parry White’s two threats: to create a “Noah’s Ark” trap on the bishop with f4, g4, and f5, or to fork the king and knight with f4 and e5. Note that 16. … Be2 does not get Black out of trouble because after 17. Re1 B-moves White gets to play the fork 18. e5+ anyway.

Notice, by the way, that the more aggressive-looking 16. f4?! would have been inaccurate because Black can play 16. … e5 himself. Black’s position is still difficult, but he is alive. If you want to beat a grandmaster, you’ve got to be precise in your execution, as Taylor was here.

The other thing I think is cool about the combination is how utterly prosaic White’s moves were. 11. e4, followed by a bunch of trades, followed by a completely ordinary pawn kick with 16. h3. A game won by prosaic methods counts exactly the same number of points as a game won by a brilliant queen sacrifice.

If you’re curious, the game continued 16. … Bh5 17. f4 Ke7 18. g4 Nxg4 19. hg Bxg4 20. Bf3. More exchanges! Black can’t escape with 20. … Bh3 because after 21. Rf2 his bishop would be on the endangered species list. So he played 20. … Bxf3 21. Rxf3 Rad8 22. Nc3 Rd2 23. Rf2 and I think I’ll stop here. It’s clearly “just a matter of technique” for White, with a knight versus two pawns and with Black’s counterplay completely neutralized. Of course, a “matter of technique” becomes more complicated when a grandmaster is sitting across the board from you, but White was up to the challenge.

In my previous blog post, I made a tongue-in-cheek list of steps to defeating a grandmaster. How did Taylor do on that list?

- Play White. Check!

- Don’t play the opening your opponent has written a book about. Check! Sengupta hasn’t written any books.

- Make him think that you’ve blundered. Fail. Taylor didn’t play any moves that looked dubious.

- Sacrifice your queen. Fail. Taylor played completely boring even trades.

- Don’t forget that he is human, not a computer. Check! The one thing that Taylor did well in this game was to go deeper than his opponent. It would be easy to shrug off moves like Nxd7 and Bxd6, thinking that White is just trading away his advantage, and besides, there’s no way that a grandmaster could overlook such obvious moves. Taylor did not take Sengupta’s word for it that Black’s position was okay, he kept on going and he discovered that it was not okay. That’s why Taylor won the game.

Of course my “list” was tongue-in-cheek; there is no list of rules that will enable you to beat a grandmaster. I’ve never beaten one myself. But I think that when it finally happens, it will be a game very much like this one. It will be very easy, and when it’s over I will wonder what all the fuss was about and why it took me so many tries to do it.

However, I do believe that point five on the above list is an important one to keep in mind. Chess is hard, and GM’s are human, and every now and then they will miss something, either because of overconfidence or plain human fallibility. Be prepared for the mistake, be confident of your ability to spot the mistake (but not overconfident), and be precise in your execution, and then you will win.

Happy new year, and I wish all my readers lots of victories in 2018!

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I had a similar experience. The first GM I beat – who was also the first GM I ever played – was top-rated Miguel Quinteros in the first round of the 1984 World Open. I then scored another upset in round 2 vs. a non-GM (before GM Farago of Hungary put a hurting on me in round 3). There must be something about knocking off a top guy in round 1 that inspires lesser players to do well again in round 2.

Whoops, my main instinct was to try to make the nonsense 10.Nc6? work. Specifically, I was trying to find something after 10…Qf8. But actually, this whole ridiculous idea gets refuted directly after 10.Nc6 bxc6 11.Qxc6 (this fork was the idea) 11…Bxf4 12.Qxa8+ Bb8!