Note: If any of you are waiting for the follow-up to my previous post, “Chicken!” (Part 2), I am delaying that post for a few days because I decided I wanted to cover it in a ChessLecture first. So look for the thrilling conclusion to the chicken saga later this week! For today’s post, I would like to follow up on an interesting question in chess psychology that I brought up in another post not too long ago. Specifically, I would like to talk about the psychology of The 41st Move.

Here’s the situation. You are in a time scramble, and you have been checking off the moves on your scoresheet instead of writing them down, as USCF rules allow you to do. (In FIDE tournaments, with the 30-second time increment per move, you are not allowed to do this any more.) Your scoresheet shows that you have just made your 40th move, and so you are past the time control. Your opponent makes his move, and now your clock is ticking again. Just to make the problem a little more difficult, let’s suppose that your opponent also does not have a complete scoresheet, or suppose his scoresheet only shows that you have finished move 39. What should you do?

(a) Play one more quick move, “just to make sure” that you have reached the time control. (After all, maybe you made a mistake in notation earlier, or gave yourself one extra check mark somehow.)

(b) Trust your scoresheet. Get up from the board, walk away, collect your thoughts, and let your flag fall.

A lot of people will choose (a). For example, I wrote in my earlier post about a game I watched in Norway where both players continued blitzing out their moves up to move 44. At that point one of the flags fell and they went to another board to reconstruct their scoresheets.

However, I am convinced, from painful experience, that the correct answer is (b). Unless you are a sloppy scorekeeper, the chance that you will lose the game by rushing your 41st move is much greater than the chance that you will lose on a time forfeit because you checked off the wrong number of moves.

Here is the game that convinced me once and for all not to rush the 41st move. I was playing against Ilan Benjamin in the 2003 Santa Cruz Cup, and this was to all intents and purposes the decisive game. I had been fighting for a draw the whole game, and by move 35 I was within sight of it:

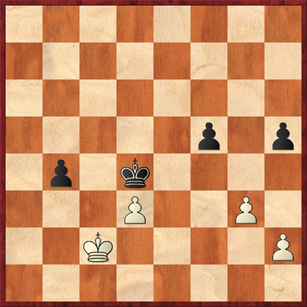

White to move.

This is, by the way, a rare example of a king-and-pawn endgame where the player with the outside passed pawn does not win. The reason is that Black’s pawns on the kingside are too weak, plus I have a little bit of rook file voodoo. He can win my pawn on h2 and get a pawn advantage (f- and h-pawns versus g-pawn), but alas, as soon as he captures on h2 I will put my king on f2 and his king will never be able to escape! I suspect that Ilan probably went into this endgame thinking it was a win, but it’s not.Â

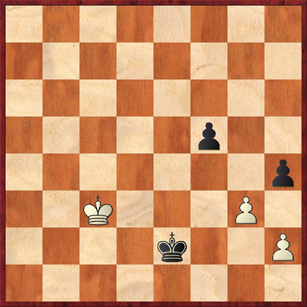

I played the only drawing move, 36. Kb3! and the game continued 36. … Kxd3 37. Kxb4 Ke4 38. Kc3 Ke3 39. Kc2 (by the way, 39. Kc4 also draws) 39. … Ke2 40. Kc3! (Even with my flag hanging, I saw that 40. Kc1?? loses to 40. … h4 41. gh f4 and Black’s pawn queens with check.) 40. … h4 (diagram 2).

Now let me explain what happened. I was reasonably confident that I had finished 40 moves. However, we were playing with a digital clock that counts the number of moves, and the clock showed I had only made 39 moves! So it was counting down my final seconds and was going to show me as overstepping the time control if I didn’t make my move!

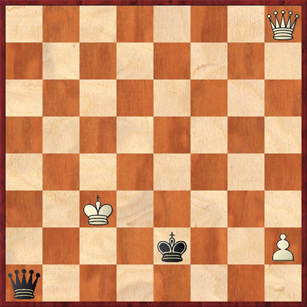

You can’t argue with technology, right? And besides, I thought that I had avoided Black’s trap with my 40th move, and therefore I thought that the pawn capture was completely safe. So I played 41. gh?? and lost the game! After we played the moves 41. … f4 42. h5 f3 43. h6 f2 (yes, I really did play on this far) I was horrified to see that he wins with a skewer after 44. h7 f1Q 45. h8Q Qa1+! (diagram 3)

Position after 45. … Qa1+ (analysis)

This is an old trick, and one that is well worth memorizing. If you have seen the movie “Searching for Bobby Fischer,” you have seen this exact trap. In the final game sequence, where Josh Waitzkin is playing against his archrival, both of them promote their pawns and then Josh hits him with the skewer-check along the diagonal. (By the way, this bears no resemblance to the actual game between Josh Waitzkin and Jeff Sarwer; the endgame was composed for the movie.)

Unlike Josh’s opponent in the movie, I resigned at move 44 rather than allow the skewer to happen.

So what happened? Why did the clock malfunction? I believe the reason must be that Ilan had forgotten to press his button or had not pressed it solidly enough at some point earlier in the game. Then I played my move without noticing that Ilan’s clock was still running. Thus the electronic clock failed to record that move pair, and so it showed only 39 moves having been made at the critical moment.

So what is the moral of the story? Do not trust technology. Do not trust your opponent. Do not trust anything except your own scoresheet — and make sure that you keep score as accurately as you can (even if you are just checking off moves).

By the way, I was very interested to see an article in this month’s (April 2009) Chess Life that makes the very same point! Check out GM Lev Alburt’s review of Garry Kasparov’s new book, Kasparov vs. Karpov, 1975-1985. In the sixth game of the first Karpov-Kasparov match, Kasparov also rushed his 41st move, and it turned out to be the losing move. Here is what Alburt has to say:

Making a quick after-time-control move is common among players of all levels; usually it’s done in order to avoid a forfeit in case you’ve missed writing down one of your moves.

Personally, I was put on the right path here by Botvinnik, who told me, “Lev, go over your games and see how often you missed a move. Then find out how many points you lost by making a 41st move quickly.”

The results? One in four hundred vs. at least three points deficit in just one hundred games! After that, I never made just-in-case-a-move-was-missing quick after-time-control move[s again].

A practical bit of chess psychology that will definitely save you points!

P.S. What should I have done on my 41st move instead? The answer is 41. Kd4! It doesn’t matter whether Black plays 41. … hg or 41. … h3; in either case, White’s king will get to Black’s f-pawn in time to save the game.