Back in April I posted an entry called “Chicken!” (part 1) that began telling the story of a game I played with a master named Rich Jackson in the 1987 North Carolina Championship. This particular tournament was one of the highlights of my chess career, as it was the second time that I won the title of North Carolina champion. The game with Jackson, which came in the second-to-last round, was my most crucial win. (In the last round I drew with another master, Randy Kolvick, and won the title on tiebreaks.)

Unfortunately, I never got around to posting part 2 of the saga! The reason is that the ending with Jackson was so interesting that I decided to make a ChessLecture out of it. So I decided to wait a week or two before putting my analysis up on this site. But then a week or two turned into a month … and two months … Every time I would get into Word Press to compose a new blog entry, I would see this unfinished entry staring accusingly at me in my “Drafts” folder.

Well, now I will finally post the entry that I meant to post four months ago. I’m sorry if I kept you all in suspense all this time! 😉

********************

In my last post I started telling the story of my game with Rich Jackson in the 1987 North Carolina Championship. We have already seen how I followed in the tradition of the great world champion Emmanuel Lasker by “chickening out” and playing a good alternative line instead of the move Rich had obviously spent his time analyzing. Unfortunately, I then blew my advantage by failing to play an elementary in-between move. Now let’s see the amazing conclusion of this game! We’ll pick up the action again after White’s 37th move, Kf3-e4:

This game is so drawn you might wonder why we’re even still playing. Well, there is one very important factor to consider: the clock. The time control for this tournament was 50 moves in 2 hours, so Rich still had a very long way to go: he had to make thirteen moves in two minutes. Instead of keeping his extra piece, he decides to give it up in order to reach a theoretically drawn R+P endgame.

This is actually not such a bad idea. In many endgames, especially if you are low on time, you can save yourself some grief by aiming for a position that you know is a theoretical win or a theoretical draw (depending on the situation). This is why we study endgames! But there is an important caveat: you had better be sure that you know how to play that theoretical endgame. It does you no good to aim for a “book draw” and then botch it!

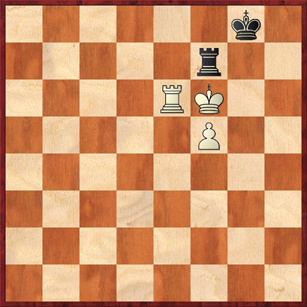

So in the diagrammed position Rich played for the “book draw” with 37. … Rg2?! Of course, I was thrilled to win his bishop: 38. Kxd4 Rxg3 39. Ke5 Ra3. (Here Fritz prefers 39. … Rg6, because it prevents White’s King from reaching the sixth rank. After 40. f5 Ra6 41. Re7 Kg8 42. Re6 Ra7 43. Kf6 Rf7+ — a drawing motif that could also have occurred in the game.)

Drawing Motif #1: White’s king reaches the sixth rank but can’t stay there.

Interestingly, this particular motif seems not to be mentioned in either of the two main endgame references in my chess library — Reuben Fine’s Basic Chess Endings or Jeremy Silman’s Complete Endgame Course. We can therefore perhaps forgive Rich for not finding it in time trouble!

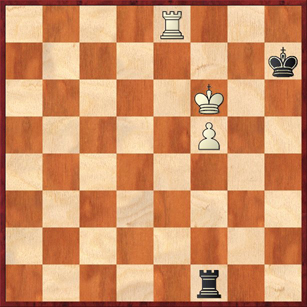

Okay, now back to the actual game after 39. … Ra3. I played 40. f5, which again Fritz queries. It says that I should play 40. Kf6, and in principle it is right: in most endgames it is more important to activate your king than to push your pawns. However, we are still in draw territory, and in fact this move leads to the second thematic draw, after 40. Kf6 Kg8 41. Rc8+ Kh7 42. Re8 Rf3 43. f5 Rf1!

Drawing Motif #2: White’s king reaches the sixth rank but he cannot advance the f-pawn, which remains under the baleful gaze of the Black rook. Black’s king goes to the “short side” of the passed pawn.

Drawing Motif #2 is mentioned in both Fine and Silman. Maybe we should call this “Position 290,” because it is discussed on page 290 of Fine’s book, and position 290 of Silman’s book! (Alas, it is position 306 in Fine, and it is on page 284 in Silman, which spoils the symmetry.) It’s also known in Silman’s book as “Going to the Short Side.” Black didn’t really have a choice in this case, but if he has to pick a side to run to with his king he should always pick the short side. That means he retains the possibility of checking White’s king on the long side. This comes into play if White continues 44. Rf8 (hoping to defend the pawn “through” the king); now Black changes plans and plays 44. … Ra1! and White’s king will have no relief from the barrage of “Long Side” rook checks on a6, a7, etc.

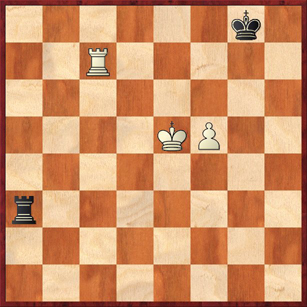

If Rich Jackson had known either of these two drawing motifs, he could have saved the game. But here is what actually happened: 40. f5 Kg8 (diagram).

Now we can see what Rich’s idea is. He is aiming for the famous Philidor position: king on the queening square (f8) and rook on the third rank (a6). That is what he has been aiming for since move 37, but there is one problem: he’s a tempo too slow. The game is still drawn, but Black cannot reach the Philidor position. He has to know either Drawing Motif #1 or #2 (aka Position 290, aka Going to the Short Side). It is quite appropriate that Silman discusses this in a section of his book called “When a Philidor Goes Bad,” because that is exactly what has happened here.

By the way, lest my comments be seen as too critical of Rich, I should say that I had no idea about any of this either. I was just doing my best to win the game. So here I played 41. Re7 Kf8 42. Kf6 Ra6+ 43. Re6, and now we see that the Philidor has officially “gone bad.” Black has not been able to cut White’s king off from the sixth rank.

Black to play and draw (2 different ways).

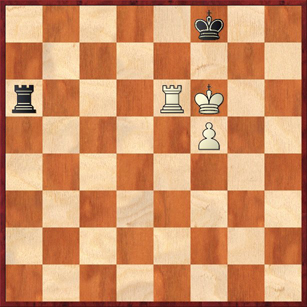

Still, Black has two good options at his disposal. He can either go for Drawing Motif #1 with 43. … Ra7, or he can go for Drawing Motif #2/Position 290/Going to the Short Side with 43. … Ra1. But instead he panicked. Remember, Rich is down to a few seconds on his clock. He’s done everything “by the book,” tried to get to the Philidor position, and all of a sudden he realizes that it hasn’t worked. So he did what so many of us do when we get flustered — he “played it safe” with 43. … Ra8??, defending against any back-rank mates. But if you look at Fine’s book, you’ll see that this violates the First Commandment of this endgame (really, all rook endgames, but especially this one): Thou Shalt Not Immobilize Thy Rook! I now played 44. Rb6, tying Black’s rook down to the back rank. Black is now lost. The game ended 44. … Rc8 45. Ra6 Rb8 46. Kg6 Rb8 47. Ra7 Rb8 48. f6 Kg8 49. Rg7+ Kh8 50. Rh7+ Kg8 51. f7+ resigns.

What a drama! It’s poetic justice that the person who called “Chicken!” ended up getting his feathers plucked, and really in an embarrassing way — because this is an endgame that a master should have been able to draw.

At the same time, it was a huge stroke of luck for me. After this game, I went into the last round with a score of 4-1, which tied me for first place among North Carolina residents. (That year, the state championship was open to out-of-state players, so there were a couple of people above me in the standings. Of course, they were not eligible to be North Carolina champions.) In the last round I was paired against Randy Kolvick, the other North Carolinian with a 4-1 score. Perhaps I will tell that story another day …

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I knew all of those ways of drawing the game, but time pressure can make one frantic. I have no doubt I could have drawn with two or three more minutes or with a five second delay clock – but in those days with the flag hanging no one knew when the flag might actually fall and many did fall prematurely. In all fairness the rest of the game should have been included – to only include the portion of the game where the opponent (any opponent) is in severe time pressure is in my opinion inappropriate and unfair.

Rich Jackson

Greenwich2mo@yahoo.com

PS You could make it up by letting me submit a game for publication that changed theory from slightly better for white to black is road kill and made ECO as the definitive last word on the line.

Hi Rich! Good to hear from you, and I am of course always willing to see one of your games. If you want you could post it in a comment, or you can send it to me by e-mail.

I’m a little puzzled by your “in all fairness” comment because in fact I DID post a large chunk of the game in the previous entry that was referenced in the first line of this entry (called “Chicken, part 1.” That post went from moves 15 to 28. In my opinion nothing very interesting happened from moves 28 to 37; the position just went from drawn to drawner. That’s why I skipped over them. The other thing is that chess books and articles look at game fragments all the time, and I’m certain that from time to time those fragments are positions where one player or the other was in time trouble. So even if I had started at move 37 without writing the previous entry, I still don’t think that this is anything particularly out of the ordinary.

But anyway, as I said, if you send me your game and if I can think of anything halfway cogent to say about it, I’ll be glad to discuss it in my blog.

{ 1 trackback }