The 2017 U.S. Masters championship in North Carolina ended last weekend with a dramatic Armageddon game between GM Sam Shankland, the tournament’s highest seed, and GM Yaroslav Zherebukh, last year’s second-place winner. Curiously, neither Shankland nor Zherebukh won the 2017 tournament: the winner was Vladimir Belous of Russia, with a score of 7/9. The playoff between Shankland and Zherebukh, who scored 6½ out of 9, was necessary because the tournament is, after all, the United States Masters, and Belous was not eligible for the title because he is in the Russian federation. It’s a situation I’m quite familiar with, having won both of my North Carolina state titles when the tournament winners were from out-of-state.

I’ve criticized Armageddon games before because they are not chess: the draw odds for Black distort the strategy of the game. Nevertheless, the battle between Shankland and Zherebukh was fascinating. Zherebukh, as Black, saved a draw out of what appeared to be a lost position, and deserved the title of U.S. Masters champion.

Whenever you see a miracle save like this, the natural question to ask is: What did White do wrong? But if you only look at the game from this point of view, you won’t get the full value from it. After all, to be a great player you have to save the losing positions as well as win the winning positions. In fact, I think that the ability to save losing positions may be a truer sign of mastery. So we should also ask: What did Black do right?

I’ll change up my usual approach and give the game without analysis first, so that you can ponder these two questions.

FEN: 8/1r3pk1/2p3p1/1q1p3p/3P3P/RPQ1P1P1/5PK1/8 w – – 0 26

26. Ra8 Re7 27. Rc8 Re6 28. Qc5 Qxc5 29. dc f6 30. Kf3 g5 31. Ke2 d4 32. Rd8 de 33. fe Re7 34. b4 Rb7 35. Rd4 Kg6 36. Kd3 Kf5 37. Kc4 Re7 38. e4+ Ke5 39. Rd6 Rc7 40. b5 cb 41. Kxb5 gh 42. gh Rf7 43. Rd5 Kxe4 44. Rxh5 f5 45. c6 f4 46. Rc5 f3 47. c7 f2 48. c8=Q f1=Q+ 49. Rc4+ Kf3 50. Qg4+ Kf2 51. Qe4 Qe2 52. Qd4 Kg3 53. Qd6 Kh3 54. Qd5 Rf4 55. h5 Rxc4 56. Qxc4 Qxh5+ 57. Qc5 Qxc5+ ½-½

We start with the question: What did White do wrong?

First, one thing that White did right was 26. Ra8! This was a key move: White realizes that Black cannot grab the b-pawn because of 26. … Qxb3 27. Qxc6, and Black cannot stop White’s queen from reaching the back rank with deadly threats.

The move 28. Qc5 looked really good to me, but it does transform the nature of the game from one where White has both middlegame and endgame potential to one where he is exclusively trying to grind out the endgame. However, I don’t see a better option. It’s hard for White to maneuver his queen to the back rank, and if he isn’t careful, Black will get some quick counterplay of his own with … Qe2 and … Rxe3! Also, Black is threatening the annoying … Qb7, which leaves White’s rook unable to find a permanent home on the eighth rank.

Shankland’s one truly head-scratching mistake was 30. Kf3? Let’s take a look at the position just before this move.

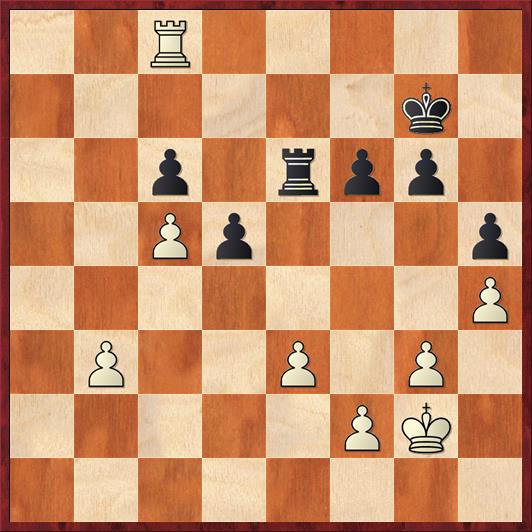

Position after 29. … f6. White to move.

Position after 29. … f6. White to move.

FEN: 2R5/6k1/2p1rpp1/2Pp3p/7P/1P2P1P1/5PK1/8 w – – 0 30

Here the move 30. Rc7+! should have been absolutely automatic, and it’s hard to explain why Sam didn’t play it. The first point is that 30. … Kh6? loses to 31. Rd7! followed by 32. Rd6, and Black’s king is too far away from the passed d-pawn after the trade of rooks. So Black is forced to retreat his king to the back rank with 30. … Kf8 or 30. … Kg8. This would have made a world of difference, as you can see from the game where Black’s king became very active and eventually wandered all the way down to f2!

The principle is that when you are ahead, you should crush any counterplay before it even gets started. Also, in R+P endgames there is always a tactical value in having your opponent’s king trapped on the side of the board. Here Shankland could have gotten that situation at absolutely no risk. It’s just a matter of taking your time and maximizing all of your possible advantages. In a regulation-length game I’m sure Sam would have done this, but in a blitz scenario it’s hard to be patient.

Shankland’s other terrible blunder was 43. Rd5+?? I’m sure that on the “day after,” he will focus on this moment as the point where he blew the game. Let’s look at the position:

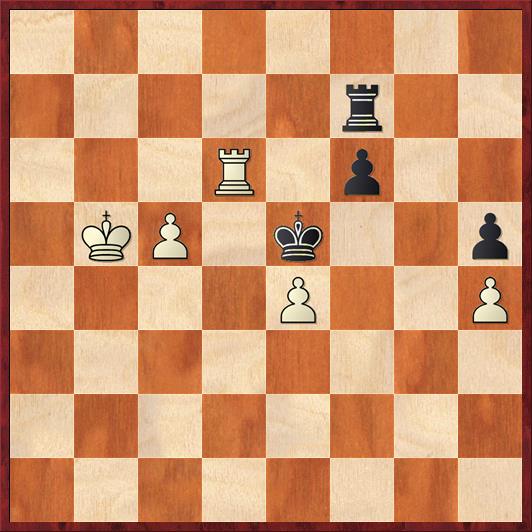

Position after 42. … Rf7. White to move.

Position after 42. … Rf7. White to move.

FEN: 8/5r2/3R1p2/1KP1k2p/4P2P/8/8/8 w – – 0 43

Let’s try to put ourselves in Sam’s shoes. Of course, 43. Rd5+ is the move any amateur would play; White just wants to make sure that he stays a pawn ahead. However, he should have realized that the h-pawn is fool’s gold. Most of the time, if the game comes down to this pawn (especially if it’s a R+P endgame, but even if it’s Q+P), it will be drawn. Sam should have focused on the c-pawn and he should have focused on improving the position of his pieces. The moves Rd5-h5 wasted two tempi and stranded the rook in an awkward position.

White has lots of winning moves here; 43. Rd8 is good and so is 43. Rd1. But the move I really like most of all is 43. Kc6! This is the sort of move that tells your opponent who is the boss. White says, go ahead and take my e-pawn. If you do, I’ll just shoulder your rook out of the way with 43. … Kxe4 44. Rd7 Rf8 45. Kd6 f5 46. c6 f4 (46. … Rf6+ 47. Kc5 doesn’t change anything) 47. c7. The pawn race variation 47. … f3 48. Rd8 Rf6+ 49. Ke7 f2 50. c8=Q f1=Q is much more favorable for White than in the game because Black doesn’t queen with check, and in fact after 51. Qc2+! the game is already over; Black has no good place to move his king.

While this last variation is a little bit technical, the principle here is again very simple: piece position is more important than pawns, especially in R+P endgames. With such a dominating king and rook, White should be winning.

Now let’s switch sides and ask: What did Black do right?

First, 26. … Re7! and 27. … Re6 was a really great defensive concept. So many of us would have been reluctant to give up the queen-rook battery on the b-file. But with these moves, Zherebukh realizes that his rook’s potential is now greatest on the e-file. He sets up the threats of … Qe2 and … Rxe3 that I mentioned before, and he also realizes that White’s rook cannot really stay on c8 because of the … Qb7 “harassing” idea that I also mentioned before. The effect of this defense is to force White to accelerate his attack: he is forced into playing 28. Qc5 before he is really ready. This is part of an elusive and little-appreciated part of chess that I call controlling the pace of the game.

Why does this matter? You might ask. After all, White was still winning the endgame. But still, this is progress for Black. Instead of having to defend both the middlegame and the endgame, he only has to defend the endgame.

Lesson 1: As the defender, use counter-threats to try to force your opponent to commit himself too early.

Lesson 2: As the defender, look for incremental gains, small ways in which you can make progress. Do not expect to save the game all in one step.

The next thing Zherebukh did that I liked was … f6 and … g5. Again, Zherebukh is trying to create counterplay. If he can get his king to the third or fourth rank, he gets much better practical chances. After 30. … g5 Sam realized he wasn’t going to get anywhere on the kingside, and he played 31. Ke2, which ran into Zherebukh’s next great move: 31. … d4!

This was the point where the position really went from hopeless to Black’s-got-a-chance. By playing … d4 and … de, Black creates huge weaknesses in White’s pawn formation, which until then had been rock-solid. Weak pawns are huge in a R+P endgame; they give your rook targets.

Lesson 3: As the defender, try to create weaknesses in your opponent’s position that can be exploited later if the game turns in your favor.

Another move that I liked was 38. … Ke5! Zherebukh refuses to be drawn into the losing tactics after 38. … Kg4? 39. e5+ Kxg3 40. ef Re1 41. hg. He also refuses to be lured into “winning a pawn” with 38. … Rxe4? 39. Rxe4 Kxe4 40. b5, when White’s outside passed pawn wins. Instead he parks his king in front of the e-pawn, recognizing that this pawn will continue to be weak.

Lesson 4: As the defender, watch out for “fool’s gold” — tactical solutions that backfire, or ways of winning back material that fatally weaken your position. Commit yourself to “infinite resistance.”

Finally, I think that Zherebukh simply out-analyzed Shankland at the end. I think that Shankland was expecting the Q+R+P vs. Q+R endgame to be won after 49. Rc4+. The idea of meeting a check with a check was too seductive; it seemed to neutralize the advantage that Black gained by queening with check. But Zherebukh realized that White would not be able to checkmate him, or really do any serious damage, with the rook on c4 being pinned. Maybe a computer could work out some way for White to unpin the rook and escape from Black’s hail of checks, but I don’t see it. Definitely this is not something that a human could work out OTB in a blitz game. The move 54. … Rf4! brings Black’s long defense to a successful conclusion: there is nothing White can do to avoid a mass liquidation.

Lesson 5: As the defender, you will have to outplay your opponent at some point to save the game. For this reason, perhaps your biggest job is psychological, because he has outplayed you in order to reach his winning position, and so it is natural to doubt whether you can turn it around. But the game changes when one player establishes a winning advantage; he is likely to start playing more conservatively, going away from the kind of chess that gave him the advantage. He might turn into a completely different player. Do not get rattled; take your time, wait for your moments and be ready to seize your opportunities when they appear.