Chess is a weird game. Sometimes the way to win is to play almost, but not quite, badly enough to lose. Then your opponent gets sucked into trying too hard, and then you can catch them on the rebound. But good luck trying to win that way. It has to be unintentional, or it won’t work!

Here’s a case in point, a game I played against the computer yesterday. I was Black in a Catalan Opening. To be honest, I just don’t know what I’m doing in that opening; I don’t know when it’s a good idea to strike back at White’s center with … c5 and when it isn’t. I usually prefer to do that because I like active defense, but sometimes it takes Black close to the brink of disaster, which certainly happened here.

Shredder (2302) — Dana Mackenzie

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. g3 d5 4. Nf3 dc 5. Qa4+ Bd7 6. Qxc4 c5

Well, here we go. The most popular alternative is 6. … Bc6, but I just don’t know what Black’s plan is in that position.

7. dc a5?!

A move that shows my confusion. My intention was to prevent White from playing b2-b4, but that is not a threat! If White plays b2-b4, that would be the time to hit him with … a5, and he will not be able to maintain the pawn on b4. Standard play for Black here (which I looked up on ChessBase after the game) is just to continue with … Bc6 and … Nbd7. White can’t really hang on to the c-pawn for long. But, as the game shows, my move isn’t totally crazy either. In fact I’d play it again, just to get White out of book.

8. Nc3 Na6 9. Be3 Rc8 10. Bg2 …

Position after 10. Bg2. Black to move.

Position after 10. Bg2. Black to move.

FEN: 2rqkb1r/1p1b1ppp/n3pn2/p1P5/2Q5/2N1BNP1/PP2PPBP/R3K2R b KQk – 0 10

10. … Nxc5?

Much more sensible is 10. … Bxc5, because it develops a piece instead of moving an already developed piece. And after 11. Bxc5 Nxc5 I get my knight to c5 anyway. According to Rybka, the position is essentially equal (+0.2 for White).

Though 10. … Nxc5 is unquestionably a blunder, it worked out well for me because I was forced to play sharper, more dynamic moves. Also, it played into the computer’s big weakness. The computer is too good for its own good! When it spots a way to win a pawn, it will abandon common sense.

That’s what happens to Shredder here. All it had to do was castle at some point, and it would have a nice working advantage. Instead it chases the win of a pawn, and the position blows up in its face. (Does the computer have a face?)

11. Ne5! Be7 12. Nxd7 Nfxd7 13. Rd1 O-O 14. Bxc5? …

Position after 14. Bxc5. Black to move.

Position after 14. Bxc5. Black to move.

FEN: 2rq1rk1/1p1nbppp/4p3/p1B5/2Q5/2N3P1/PP2PPBP/3RK2R b K – 0 14

A serious positional mistake by the computer, giving away one of its prize bishops for the sake of winning a pawn. It doesn’t know what any human 2300 player would know — before plunging into tactical complications, finish your development! White just needs to castle.

14. … Rxc5!

This loses a pawn, but with tremendous compensation.

15. Qa4 b5!

Necessity is the mother of invention. I still couldn’t see how all the tactics would work out, but I knew I had to do this or else just lose.

16. Nxb5 …

Position after 16. Nxb5. Black to move.

Position after 16. Nxb5. Black to move.

FEN:3q1rk1/3nbppp/4p3/pNr5/Q7/6P1/PP2PPBP/3RK2R b K – 0 16

Now is when things get seriously wild!

16. … Nb6! 17. Qb3 …

Other options: (a) 17. Rxd8? Rxd8! and White has to lose his queen or get checkmated. (b) 17. Qe4 is best according to Rybka, but after 17. … Qxd1+! 18. Kxd1 Rxb5 Black’s pieces control the board and White’s king is in trouble. (c) 17. Qxa5 Qxd1+! 18. Kxd1 Rd8+ 19. Qd2 Rxd2+ 20. Kxd2 Rxb5. To be honest, I didn’t know if any of this would work. I was just blitzing out forced moves!

17. … a4 18. Rxd8 ab 19. Rxf8+ Kxf8 20. Nc3 ba 21. O-O?? …

It’s ironic that after I criticized Shredder for not castling earlier, now it was almost the worst possible move! I was stunned that it didn’t play 21. Nxa2. Of course, I would win back my pawn with 21. … Rc2 with dead equality. I would certainly not have objected to a draw. Until this moment I was just fighting to survive. Now it started to dawn on me that I might actually win this game!

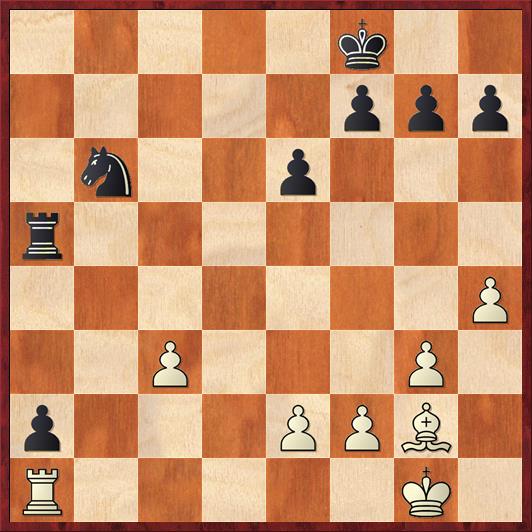

21. … Ra5 22. Ra1 Bf6 23. h4 Bxc3 24. bc …

Position after 24. bc. Black to move.

Position after 24. bc. Black to move.

FEN: 5k2/5ppp/1n2p3/r7/7P/2P3P1/p3PPB1/R5K1 b – – 0 24

Here I took the one time-out per game that I allow myself against the computer. Of course I wanted to maneuver my knight to b3 and win White’s rook, but I wasn’t quite sure that 24. … Nc4 would work because of 25. Be4 Nd2 26. Bc2. How does Black make progress?

I gradually realized that a little prophylaxis would do just the trick. After 24. … f5! White’s bishop has no route to get to the queenside. Well, he can sort of get there with 25. Bf3 Nc4 26. e3 Nd2 27. Bd1. But there’s a big difference between d1 and c2. Black would now like to play 27. … Nb1 and win the c-pawn, but after 28. Bb3 both the e-pawn and the a-pawn are hanging. Once again, prophylaxis is the right strategy! Black should play first 27. … Ke7! to defend the e3 pawn. As long as the knight is on d2, White can’t bring his bishop to b3. In order to combat this, White has to play 28. f3 to bring his king in. (28. Bc2 is too slow because after 28. … Kc6, Black marches his king up the board and wins the c-pawn.) Then 28. … Nb1! is winning.

Shredder probably saw all this, because it decided instead to throw in the towel with 25. e4. I continued 25. … Nc4 26. ef Nd2 27. fe Nb3! The knight reaches its destination, White is forced to sacrifice his rook, and the game is won for Black.

Whether you’re in a tournament or just at home playing your computer, it’s always pretty exciting to win a game when you were just trying and hoping for a draw.

To answer the question, when is it good to play bad moves? Well, if you’re going to make mistakes, the best time is in the opening. There are no redeeming features of mistakes in the endgame or middlegame; all they do is cost you points or half-points that you should have won. Opening mistakes, on the other hand, sometimes give you a chance to fight back. Still, I’d rather not make any mistakes at all!