The year 1988 was a unique time in my life, both chessically and personally. In 1987, I had just won my second North Carolina championship and earned the National Master title. In hindsight it seems like the one period of my chess life when I was brimming with confidence; I had achieved two of my greatest goals and it looked as if the sky was the limit.

There was another magical thing going on in my life at the same time. In April, just three weeks before the game I’m going to show you, I had started dating Kay, who would eventually become my wife. I was completely, totally in love. When you find a love like that, it turns your life upside down and makes you feel as if there is no obstacle you can’t overcome.

In short, everywhere you looked, my life was pink fluffy unicorns dancing on rainbows. It was in this frame of mind that I drove to Atlanta, Georgia to play in the 1988 Georgia Congress, held on the weekend of April 30 and May 1.

There were three other masters at the Georgia Congress: grandmaster Boris Kogan (2576) and national masters Guillermo Ruiz (2323) and Douglas Brown (2264). I was seeded fourth (2202). Obviously Kogan was a huge favorite, and I had no expectations of finishing first. But that’s what happened!

Strangely, I didn’t have to play any of the other masters. But that’s not as uncommon as you might think. The life of a master is to play almost all of your games against lower-rated people, and only if you win all of them, you might get to play one or two games against fellow masters in the last rounds. (At least that’s the way it works in the U.S. It’s probably different in Europe.)

I had three strokes of luck on the final day. Stroke of luck #1: Going into the last round, Kogan, Brown, and I were all tied at 4-0. Because Kogan and Brown were the higher-rated players, they were paired against each other, while I was paired against the highest-rated player with 3½ points, an expert named Mark Coles (2191). Stroke of luck #2: I beat Coles, as you’ll see below. Stroke of luck #3: Brown managed to hold grandmaster Kogan to a draw. Thus I won clear first place at 5-0, while Kogan and Brown split second place with 4½-½.

That was a lot of luck, but when you have pink fluffy unicorns on your side, everything is possible. I was thrilled to score 5-0, the first time I had ever done that in a USCF tournament. I was also excited to win an open tournament for the first time, and to come in ahead of a grandmaster! It would be nice if I could say that this was the first of many tournament victories in my life, but that’s not true. It was the first of two and a half. (Three and a half if you count team tournaments.)

The last thing I remember about the tournament was the drive home. It’s a seven-hour drive from Atlanta to Durham, and I had to teach the next day, so I drove straight through the night. Until about 3 am I was fine, running on adrenaline, but the part from 3 am to 6 am seemed endless. I was glad that so few cars were on the road. But the end of the drive was nice. It’s fun to watch people starting their days when you’ve been up all night; it somehow makes you feel older than they are, because you’re still working on the day before.

Now let me show you my last-round game against Coles. One odd thing about this game is that I hardly ever felt as if I was winning. It felt more as if I was following a rainbow, not really knowing where it was going to lead me. A pot of gold? Or just a cold shower? When in the end I saw how all the pieces of the puzzle fit together, I was amazed. The whole endgame was unplanned, and yet it looks exquisitely planned. Take a look for yourself!

Mark Coles — Dana Mackenzie

Georgia Congress 1988

Ruy Lopez

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 a6

This may look like a surprise, but yes, this game was before I started playing the Bird Variation (3. … Nd4) regularly. My first Bird game was in 1987, and from about 1988 to 1992 I played both the Bird and the Steinitz Deferred as Black. But my opponent had other ideas: the Exchange Variation.

4. Bxc6 dc 5. Nc3 Qd6 6. h3 …

Staying away from the most theoretical lines. My opponent is evidently not interested in playing the variations with O-O, Bg4, h3, h5.

6. … Ne7 7. d3 g6 8. Be3 c5 9. Qd2 Bg7 10. Bh6 O-O

Castling into an attack, but I had faith in my pieces.

11. O-O-O b5 12. g4 Bb7 13. Rdg1!? …

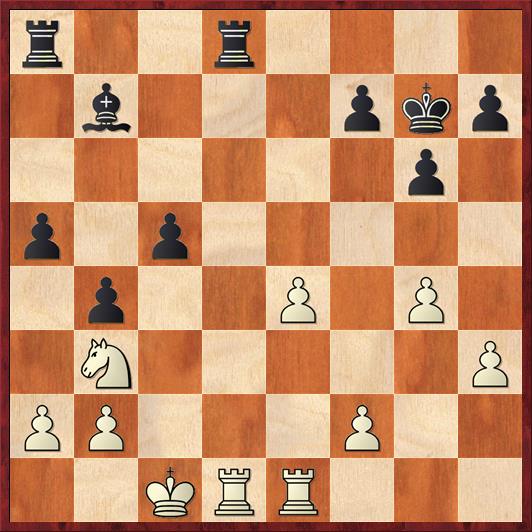

Time for our first diagram.

Position after 13. Rdg1. Black to move.

Position after 13. Rdg1. Black to move.

FEN: r4rk1/1bp1npbp/p2q2pB/1pp1p3/4P1P1/2NP1N1P/PPPQ1P2/2K3RR b – – 0 13

Looking at this position, you wouldn’t expect this game to be decided in the endgame. It looks as if both players are putting their chips all-in on opposite-side pawn storms. One of the things that makes the game so interesting, and tense, is that there are all these possibilities of full-scale mayhem that could break out any moment… yet instead the game follows a more placid course.

Here, for example, I could play the saucy move 13. … f5?! 14. gf Nxf5, exploiting the pin on the main diagonal. For what it’s worth, I think this would have been completely playable. But the idea is wrong in principle because I’m playing on the wrong side of the board. I’m opening up the kingside, which is just what my opponent wants. It makes more sense to continue my assault on the queenside, which is faster than my opponent’s kingside attack and is (mostly) risk-free.

So instead I played 13. … b4 14. Nd1 c4!, making use of my pressure along the long diagonal but in a different way. Here, interestingly, I made a miscalculation. If my opponent had played 15. h4, I was thinking about 15. … c3?! 16. bc bc 17. Nxc3 Qa3+ 18. Kd1 Bxh6 19. Qxh6 Qxc3. This wins a piece but loses the game after 20. Ng5! Hopefully I would have changed my mind and played a more circumspect defense like 15. h4 f6, keeping knights and other stray objects away from my king. But we’ll never know, will we? Fortunately, the unicorns were protecting me. This line is an example of how quickly the position could have turned into mayhem if either player had made a misstep.

Instead my opponent played 15. Bxg7 Kxg7 16. Ne3, a positional and logical approach based on pressuring my center with his knights. After 16. … cd 17. cd Rfd8 we arrived at the following position.

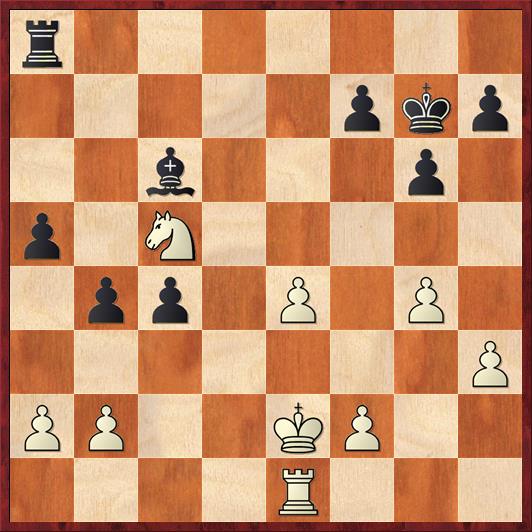

Position after 17. … Rfd8. White to move.

Position after 17. … Rfd8. White to move.

FEN: r2r4/1bp1npkp/p2q2p1/4p3/1p2P1P1/3PNN1P/PP1Q1P2/2K3RR w – – 0 18

Here my opponent played a very impressive move. Obviously Black is threatening the d3 pawn. 18. Ne1 doesn’t work because of 18. … Bxe4, and 18. Kc2 doesn’t work because of 18. … Qc5+ followed by … Bxe4. However, if I were White I would have been sorely tempted by the possibility of sacrificing a piece with 18. Nf5+?! I don’t think this works, and the computer doesn’t either, but in the heat of battle it’s tough to back away from this possibility and instead play the following move:

18. Rd1! …

Psychologically this is one of the hardest things to do in chess — to “take back” a move that you played earlier (13. Rdg1). It was also a big relief to me because it seems as if White is no longer serious about his kingside attack. But I gradually realized that my position was not as wonderful as I expected, because Nc4 is a serious threat. I have a bunch of weaknesses — the pawns at b4 and e5, and the loose pieces on b7 and e7. The “mayhem” move 18. … Qxd3?! does not work after 19. Qxb4. So I gradually calmed down and realized that I have to put away my sword, too.

Incidentally, Rybka completely agrees that 18. Rd1 was the right move. It rates the position at 0.11 pawns in Black’s favor (basically equal), while after the next best move (18. g5) it would be 0.60 pawns in Black’s favor.

18. … Qc5+

Perhaps more peaceful than necessary, but I don’t think it’s a mistake. One of my quirks (weaknesses?) is that I’ve always been interested in queenless middlegames.

19. Qc2 Qxc2+ 20. Nxc2 …

Rybka slightly prefers 20. Kxc2, but the important thing is that White has a plan: he’s setting up the d3-d4 break, liquidating his one big weakness.

20. … Nc6 21. Rhe1 a5 22. d4 ed 23. Ncxd4 Nxd4 24. Nxd4 c5 25. Nb3 …

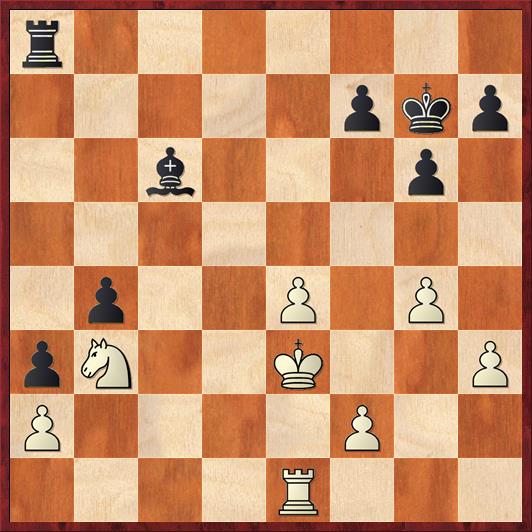

Position after 25. Nb3. Black to move.

Position after 25. Nb3. Black to move.

FEN: r2r4/1b3pkp/6p1/p1p5/1p2P1P1/1N5P/PP3P2/2KRR3 b – – 0 25

Up to this point in the game, I don’t think that White — or for that matter, Black — has made a single move that you could call a blunder. In fact, I would say that White has played very good, plan-ful chess, and both sides have resisted the temptation to venture into premature and probably unsound tactics.

Nevertheless, it’s too early to call the game a draw. Black still has the advantage of the bishop versus the knight (the advantage White gave up on move four). The closer we get to the endgame, the more significant that difference feels. As Richard Reti explained in Masters of the Chessboard, in a bishop versus knight endgame the knight needs an outpost, a secure square it can’t be chased away from. When it lacks outposts, it has a tendency just to get pushed back and back into more passive positions. White’s knight looks to me like a prototypical case of a knight without an outpost.

There are two reasonable plans here for Black, to play … c4 or … a4 (in the latter case, exploiting the uncomfortable position of White’s king on the c-file). I eventually chose the first one on principle, the principle that the potential passed pawn is the one that you should push. However, I was also acutely aware that I might be getting lured into pushing my pawns too far too fast. In fact, that may have been my opponent’s intention. I had no way of seeing at this point how it was all going to work out.

25. … Rxd1+ 26. Kxd1 c4 27. Nc5! …

Another most impressive move by White. How the heck did he lose this game? Ironically, during the game I thought this was a bad move, because it nearly gets the knight trapped, and in my notes to the game later I gave it a question mark. However, looking at it now, 28 years later, I’m convinced that it is much better than the alternatives. The passive moves 27. Nd2 and 27. Nc1 fall into exactly the trap that Reti warned about, the knight becoming less and less mobile. Although c5 isn’t technically an outpost square, it turns out to be annoyingly hard for Black to oust the knight from that square.

27. … Bc6

Leaving the knight with no flight squares.

28. Ke2? …

According to Rybka, this is White’s first serious mistake! White should have played 28. Kd2, with the plan of playing Rc1 and pressuring the c-pawn. With the king on e2 as in the game, Rxc4 is not a threat because it gets pinned by the bishop.

Chess games can be decided by the tiniest of nuances!

I find it hard to criticize White’s play because he did have a plan; it just wasn’t the best plan. However, it would be very hard to look at the position without a computer and say with any confidence that Coles’ plan is worse than Rybka’s.

Position after 28. Ke2. Black to move.

Position after 28. Ke2. Black to move.

FEN: r7/5pkp/2b3p1/p1N5/1pp1P1P1/7P/PP2KP2/4R3 b – – 0 28

I said before that c5 was almost as good as an outpost for White’s knight because it’s not clear how Black can attack it. But after Black’s next move, it becomes clear!

28. … a4!

The threat is … Ra5. How does White save his knight?

29. Ke3! …

That’s how! White’s king turns into a fighting piece.

29. … a3!

This is the part I wrote about before the game, where it feels as if I’m following some ever-retreating rainbow. Why am I pushing the a-pawn? What is the point? I really didn’t know. I only knew that nothing else works.

30. b3 …

Like move 28, this is a mistake according to Rybka. Nevertheless, I cannot bring myself to give it a question mark. Rybka says that 30. Rb1 is forced, with a 0.59-pawn advantage for Black. However, 30. Rb1 is the fourth move I would consider as White, after 30. b3, 30. ba, and 30. Kd4, and it is very far from obvious what makes Rb1 better than any of these other moves. In my opinion, 30. b3 is the simplest and most logical move. It has the drawback of allowing Black a tactical shot, but I suspect that my opponent allowed the tactic on purpose because he thought the position was still drawn.

30. … cb 31. Nxb3 …

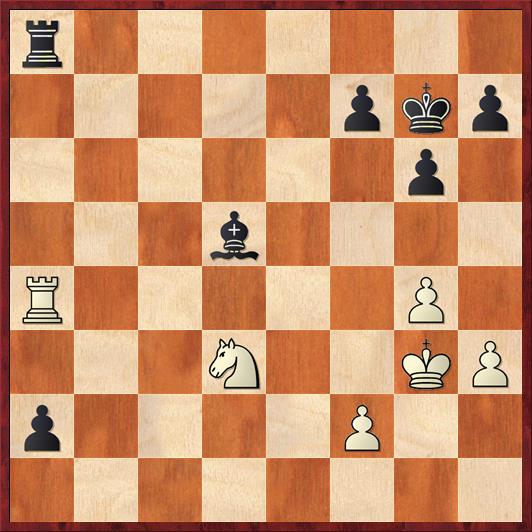

Position after 31. Nxb3. Black to move.

Position after 31. Nxb3. Black to move.

FEN: r7/5pkp/2b3p1/8/1p2P1P1/pN2K2P/P4P2/4R3 b – – 0 31

Now at last Black wins a pawn, using a little trick that is very easy to see:

31. … Bxe4!

Of course White cannot take because of the x-ray check: 32. Kxe4?? Re8+. Black is happy to win a pawn, of course, but what is of much more consequence is that his bishop is finally liberated to start harassing White’s kingside pawns. In fact, the final eleven moves turn into the most marvelous symphony — or perhaps a duet, played by Black’s bishop and rook. Once again I have to say that I didn’t see how it would all work. I was just following the rainbow and hoping it would lead somewhere.

32. Kd4 Bg2 33. Re3? …

To have any chance, White has to give up the h-pawn and try to liquidate the queenside as fast as possible, with 33. Kc5. He now loses by force.

33. … Rc8!

A key first step, cutting the king off from the queenside pawns.

34. Nc5 …

Renewing the threat of Kc4.

34. … Bf1!

In the nick of time, the bishop takes the c4 square away again.

35. Rb3 …

Okay, White says, I can do it without the king.

35. … Rd8+ 36. Ke3 Re8+ 37. Kf3 …

The king is pushed farther and farther from the action as it attempts to guard the second rank. Now Black shifts his attention back to the queenside.

37. … Bc4!

I think that this was the point where I could finally see the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

38. Rxb4 Bxa2 39. Ra4 …

White is just a move away from being able to eliminate the a-pawn. But he will never get the chance.

39. … Bd5+ 40. Kg3 a2 41. Nd3 Ra8! 42. White resigns

Final position. White resigns.

Final position. White resigns.

FEN: r7/5pkp/6p1/3b4/R5P1/3N2KP/p4P2/8 w – – 0 42

As a mathematician I love the geometry of this final position, the way that the bishop defends both the rook and the a-pawn. As a chess-player, I can’t get over the way that the rook and bishop outmaneuvered the numerically superior forces of White’s rook, knight, and king. How was this even possible? I just can’t figure it out. I think it was the unicorns.

{ 7 comments… read them below or add one }

I was on the wrong end of such a situation in a tournament that had over a hundred people and only five rounds. I was one of the favorites to win it, but in round 3 I encountered someone who prepared ahead for me and found a way to force a 3-fold repetition with White against my CK. 4.5 out of 5 was only enough for 2-3, and even with someone else and not the guy who drew me. A guy, however, managed 5-0.

I haven’t been on the wrong end of it, but I’ve been on the right end twice! I’ll write about the second time in my next “Memorable Games” post.

This is probably a fairly common situation, although I think it’s becoming less common as there are fewer one-section open tournaments than there used to be.

I won my first Open in a similar way: two much stronger players neutralizing each other in the last round, while I snuck past.

It’s interesting looking back at these old games. My first (and so far only) win against a master was in 1987, just before I stopped playing competitively. For years I had a narrative of how I’d won that game: I was in a completely restricted French position, reduced to shuffling my rook back and forth, and then she sacrificed the exchange to open the position and my pieces flowed out through the opening and pursued her king relentlessly.

When I came back to competition in 2014 I hunted down the game online. To my surprise, my position had been much less bricked up then I recalled, and after the exchange sacrifice my pieces flowed out and relentlessly pursued…a bishop, which got into tactical trouble and went lost. The game is is easily recognizable as mine, but it’s not exactly the game I’d been describing. Memory is a strange thing.

A powerful denouement, nice!

Assuming that the Doug Brown who helped you by drawing Kogan is the one I’m thinking of, he was a good friend of mine in my youth. We were both part of the “South Jersey Seven” – a group of friends from southern New Jersey who grew up playing chess together during the Fischer Boom and all became masters. (Before us, the only master from that area was Leroy Dubeck, who was USCF President for a while.)

Only two of us still play at all these days; I think Doug gave up chess shortly after the tournament you wrote about. Nice to see a reference to him after all these years.

Thanks, Dave! This is why it’s so great writing a blog; I can (sometimes, if I have the right readers) learn new things about my opponents or even about other people I’ve encountered. BTW, it has to be the same Doug Brown. The USCF ratings page shows that he quit playing in tournaments in the early ’90s. If you’re still in touch with him, I’d love to see how he drew against Kogan.

Dana – Sorry, but I’ve been out of touch with Doug since he gave up chess. So I’m afraid his draw with the late great Boris K. will always be a mystery. (My good friend Stuart Rachels, who moved from prodigy to U.S. co-champ with lots of training from Kogan, speaks very highly of Boris as a chessplayer and as a person.)