Today was Tuesday, my regular day for Aptos Library chess club. A photographer came to take some pictures, because the library is preparing promotional material for a bond measure to support the public libraries in Santa Cruz. They wanted pictures of the good things that the library does for the community, and they sure picked the right day to come to our chess club! We had one of the best and most animated lessons I’ve ever seen. I hope the pictures will convey in some way the energy and excitement we had today.

What makes a good lesson? Well, first and foremost, good students. Today, in addition to my regulars, we had two newcomers who said that they have another chess coach (probably my friend Gjon Feinstein, though I’d have to check with him to make sure). In any case, they impressed me a lot, and made a great contribution to our discussion.

The other thing that makes a good lesson is an exciting game, and for that I want to give thanks to one of my blog readers, David Gertler.

David is a National Master from Delaware, several times state champion, and in fact the current champion. [Edit on 4/20: changed “co-champion” to “champion”.] We went to the same college (Swarthmore College), although we didn’t quite overlap. I graduated in the spring of 1979 and he arrived in the fall of that year. It was fun to correspond with him by e-mail, because we knew a lot of the same people, both students and teachers, even though we’ve never met each other.

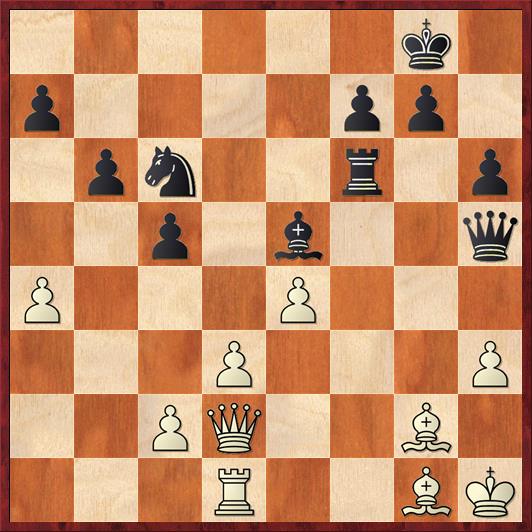

Anyway, he sent me one of his games from the recently concluded Delaware championship. The lesson started with the following position.

Position after 29. Bg1. Black to move.

Position after 29. Bg1. Black to move.

FEN: 6k1/p4pp1/1pn2r1p/2p1b2q/P3P3/3P3P/2PQ2B1/3R2BK b – – 0 29

David is Black, and his opponent is Drew Serres, an expert. After we went through the standard three questions I tell the kids always to ask (Who is ahead in material? What is my opponent threatening? Do I have any good checks or captures?), one of the new kids raised his hand. “White’s king doesn’t have any moves,” he said.

A very perceptive observation! I made sure that everyone understood why, and then I said, “When your opponent’s king can’t move, that means that if you check him, it’s often checkmate. So is there any way we can put him in check?”

Now I got my second surprise, because one of the regulars, a boy named Atlee, raised his hand and said, “Rook to f3.”

Which is exactly the move (29. … Rf3!) David Gertler had played! In other words, my kids had solved the puzzle exactly thirty seconds into the lesson.

Some days that could be a disaster, but not today. First I asked Atlee what he planned to do if I played 30. Bxf3. He correctly said he would play 30. … Qxf3+, and sure enough, we have put the king in check when he has nowhere to go to. “Is it checkmate?” I asked.

Okay, well, that was an easy one. I got about ten people telling me that White could play 31. Qg2. “Then what can Black do?” I asked. A smaller number, but still more than one, said 31. … Qxd1+, which is a decisive win of material.

Then I got my third surprise of the day, because one of the kids asked, without my prompting, “But White doesn’t have to take the rook.” Indeed he doesn’t! Many an attack has foundered because people played sacrifices and the opponent didn’t take them. He has no obligation to cooperate with you to set up your moment of glory.

So the search was on for constructive moves for White, and this is why David’s game was such a terrific one for teaching. There are a lot of different defenses White could try, and as far as I can tell all of them except one lose beautifully.

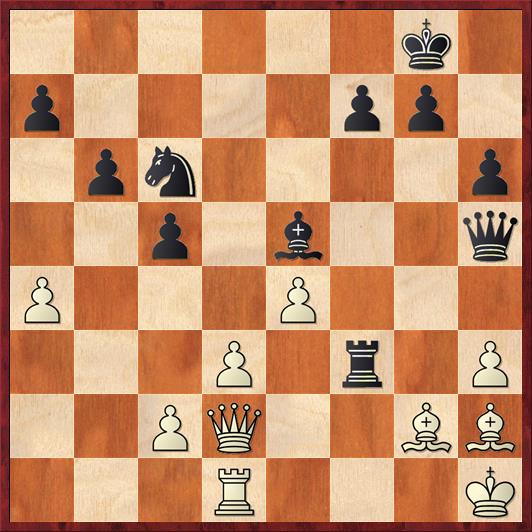

The first alternative that the kids suggested was 30. Rf1 (diagram 2).

Position after 30. Rf1 (analysis). Black to move.

Position after 30. Rf1 (analysis). Black to move.

FEN: 6k1/p4pp1/1pn4p/2p1b2q/P3P3/3P1r1P/2PQ2B1/5RBK b – – 0 30

I expect that none of you will find it hard to figure out what is wrong with White’s move, but nevertheless I think it’s a good one to start with. First, because it lets us see a variation where Black’s thematic sacrifice works, and second, because 30. Rf1 would otherwise be a very logical defense, trying to trade off Black’s most dangerous attacker.

Unfortunately, on f1 the rook turns out to be just as loose and fork-able as on d1. Black wins with 30. … Rxh3+! 31. Bxh3 Qxh3+ 32. Bh2 Qxf1.

That’s easy and it takes about ten seconds to read, but actually in real classroom time it took quite a bit longer, maybe five or ten minutes. The reason is that all of the kids are shouting out ideas, or raising their hands, or wanting to go back to previous lines, etc. It takes a certain amount of classroom management to keep things on track. Also, one has to look at 31. Bh2 even though it’s really bad, and in fact one of the girls in the class, Willow, came up with the neat idea of 31. … Rxh2+ 32. Kg1 Rxg2+ 33. Kxg2 (33. Qxg2 is better but still losing) Qh2+ 34. Kf3 Qxd2. All the boys were saying no, no, 32. … Rxg2+ is a terrible move, so I took particular pleasure in showing them that it works quite well, thank you.

After this one of the new boys said, “But what if we don’t move our rook, and just play a random pawn move?” That’s a great question, too. There actually aren’t very many “random pawn moves,” but we tried 30. c4 and saw that White is also dead after 30. … Rxh3+ 31. Bxh3 Qxh3+ 32. Bh2 Qf3+ 33. Kg1 Bd4+. (A better “random pawn move” would have been 30. c3, but White loses basically the same way after 30. … Bf4 followed by 31. … Rxh3+.)

At this point I had to call a halt to the lesson because we had already gone 20 minutes. We usually go 15 minutes at most, but the kids had been so into it that I didn’t want to stop. However, after 20 minutes I did notice a couple kids in the back starting to look less engaged, so I thought it was a good time to stop.

Unfortunately, this meant we didn’t get to look at what I consider to be White’s best defense. One of the kids even started to get the right idea: “What about moving the bishop on g1?” He didn’t ever pin down where he wanted to move it to, but in fact I think that 30. Bh2! was the right move (diagram 3).

Position after 30. Bh2 (analysis). Black to move.

Position after 30. Bh2 (analysis). Black to move.

FEN: 6k1/p4pp1/1pn4p/2p1b2q/P3P3/3P1r1P/2PQ2BB/3R3K b – – 0 30

This is the one move that seems to disrupt the timing of Black’s attack. There isn’t time for 30. … Nd4 because of 31. Bxe5. There isn’t time for 30. … Bxh2 because of 31. Bxf3! Qxh3 32. Qg2. And the thematic sacrifice 30. … Rxh3 doesn’t work because of 31. Bxh3 Qxh3 32. Qg2. The best move that I’ve been able to find is 30. … Rf2 31. Qxf2 Qxd1+ 32. Bf1, when basically the only thing that Black has accomplished is a fancy exchange of rooks. Black is still much better, because he started out a pawn ahead and he still is, but the game is not over yet — there’s still some work to do.

But there wasn’t time to talk about this, and the uncertainty of this line might have detracted from the lesson.

It’s also a pity that we didn’t have time to see how the actual game went, because that was instructive, too! In the actual game, Serres played 30. Re1 (diagram 4).

Position after 30. Re1. Black to move.

Position after 30. Re1. Black to move.

FEN: 6k1/p4pp1/1pn4p/2p1b2q/P3P3/3P1r1P/2PQ2B1/4R1BK b – – 0 30

If we had had enough time, this would have been a good spot to teach them one of my favorite sayings: “Invite everyone to the party.” Gertler came up with the superior move 30. … Nd4!, bringing in the one piece that was not yet participating in the attack. Now 31. Bxf3 walks into a multiple fork after 31. … Nxf3. Nothing else works, either. 31. Bh2 is too late because of 31. … Bxh2 32. Kxh2 Rxh3+! once again setting up a fork on f3. Putting the question to the knight with 31. c3 doesn’t work because the knight doesn’t have to answer the question: instead Black plays 31. … Rxh3+! 32. Bxh3 Qxh3+ 33. Bh2 Bxh2 34. Qxh2 (or, more subtle, 34. Qg2 Qh4!) Qxh2+ 35. Kxh3 Nf3+.

With no good options, White played 31. Bxd4, but this walked into a mating net: 31. … Rxh3+! 32. Kg1 (or 32. Bxh3 Qxh3+ 33. Kg1 Bxd4+, and White has to give up everything — his rook, his queen and his king in short order) 32. … Bxd4+ 33. Kf1 and now either rook sacrifice wins. Gertler played 33. … Rh1+! 34. Bxh1 Qxh1+ 35. Ke2 Qh5+! and White resigned in view of 36. Kf1 Qf3+.

A neat combination! It has so many different ideas — the sac on h3, the various queen deflections, the various forks on f3 with the queen or the knight, mating nets with the queen on h3 and the bishop on d4/e3, and even a little x-ray check in Willow’s variation. It was fun to work out how the ingredients fit together in slightly different ways in each line. The only thing that’s a little bit disappointing is that White might have been able to put up better resistance with 30. Bh2, but that’s chess for you. You force your opponent to make difficult decisions, and if they’re human they won’t always be able to hold up under the pressure.

Congratulations to David on a nice win and on his state title, and congratulations to the kids in my chess club for seeing so much.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Dana – Thanks for your kind comments. I’m delighted that my game served as good lesson fodder for you and your students.

You’re right that 30. Bh2 was White’s best chance to hold out. In the line you give, 30. … Rf2 31. Qxf2 Qxd1+ 32. Bf1, Black can play 32. … Bxh2 33. Kxh2 Nb4, winning a second pawn, but at least the game still continues.

After I had found the concluding combination with 33. … Rh1+, I didn’t look for anything else, so I didn’t notice the more obvious win with 33. … Rf3+. But as the game went, I like how the long-range check 35. … Qh5+ leaves him only one legal move (which walks the King back into immediate disaster). When chess geometry works, it can be beautiful.

Anyway, thanks again. I play few tournaments these days, but I really enjoy competing for the state championship. [P.S. That game made me this year’s solo champ, not c0-champion as you stated.]

Regards,

Dave Gertler