I couldn’t believe it when I got into Facebook this morning and saw a stream of testimonials to Emory Tate. International Master Emory Tate: many times Armed Forces champion, a person full of wit and passion (especially for chess), and a chess player second to none in his imagination and attacking ability.

I’m warning you now, this is going to be a long post, so settle in for a good read. Tate truly died in the saddle: He was playing yesterday in a tournament in San Jose, collapsed in the middle of the game and died, apparently of a heart attack. He was born in the year that I was: 1958. This one really hits home. When Walter Browne died earlier this year, it was a similar shock, but at the same time you could see how frail he was. But this one really came out of nowhere.

To explain what made Tate different from all other top-level masters, I think it might be useful to draw an analogy with table tennis. Years ago, everyone played Ping-Pong with hard rubber paddles, and the name of the game was power. Slam, slam, slam, overcome your opponent with reaction time, speed and bravado. Then the soft rubber paddles came in that allowed players to put a ridiculous amount of spin on the ball, and all of a sudden the game changed completely. The new game was all about craft and guile, and the old-fashioned power players could no longer compete for championships.

That’s what Emory Tate was: an old-fashioned power player. When you get beaten by most International Masters or Grandmasters, you sometimes feel as if you haven’t really had a fair match. They don’t seem to do anything special; they just trick you, or squeeze you to death ever so gently. That wasn’t the way with Emory Tate. When he beat you, you knew you had been beaten. Unfortunately, his style doesn’t win national championships. But it does produce epic, memorable games, and it catches even grandmasters off-guard sometimes. One testimonial I read said that Tate has won 80 games against grandmasters.

I gave a ChessLecture one time about Emory Tate called “My Favorite Opponent,” which he was. I played him five times, with a score of 1 win, 2 losses and 2 draws — a record that I’m proud of. Almost every game was exciting and hard fought, and in almost every game I had chances to win or to draw. That was the thing about Emory. He wasn’t afraid to take risks, even against lower-rated players. So you could catch him sometimes. His style was a good match for mine.

I’d love to show you my win against Emory, but because this is a testimonial, I won’t do that. I want to show you Emory in his element, and the best example of this was a game that we played in Ohio, in the 1996 Cardinal Open.

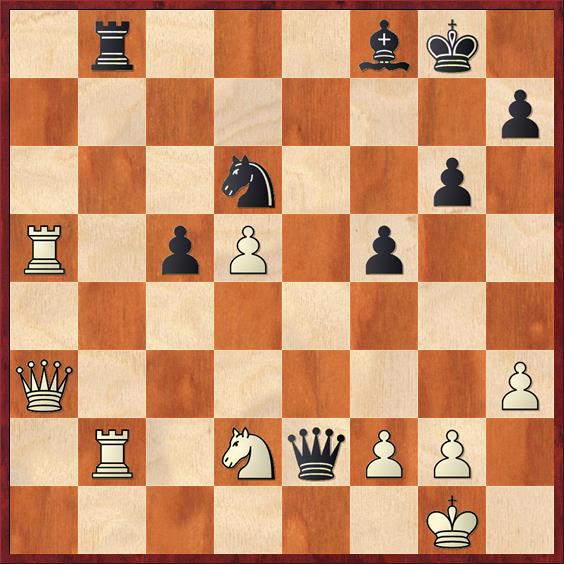

Position after 23. Bh6. Black to move.

Position after 23. Bh6. Black to move.

FEN: 1r3rk1/2q3bp/1n4pB/2pPpp2/b1P5/Rp1B3P/1P1Q1PP1/4RNK1 b – – 0 23

Here, rather surprisingly, Rybka says that the position is equal. But as White, I felt that I was barely hanging on. I had just played 23. Bh6 in an attempt to exchange off Black’s dark-squared bishop, which is eyeing my b2 pawn in a most menacing way.

Emory’s next move may not be objectively best, but it is vintage Emory Tate. He is determined to open the diagonal for that bishop, and he absolutely does not care if he has to sacrifice an exchange to do it. He played 23. … e4!? I played 24. Bf4 and he replied 24. … Qb7. And here, like a sucker, I took the bait.

The computer says I should simply retreat my bishop; after 25. Be2! Ra8 26. Ne3 White actually has a 0.5-pawn advantage, according to Rybka. This is why grandmasters (usually) beat Emory. His move … e4 was too impulsive; White has succeeded in blockading the kingside pawns and his previously disorganized pieces are starting to work together nicely. Against a White player with craft and guile, and most importantly the discipline not to take the material, Emory might not have won this game.

But that wasn’t me. For me, the position was all about hard-rubber table tennis. Power versus power. So I took the rook: 25. Bxb8 ed 26. Bd6 Nxc4 27. Qxd3.

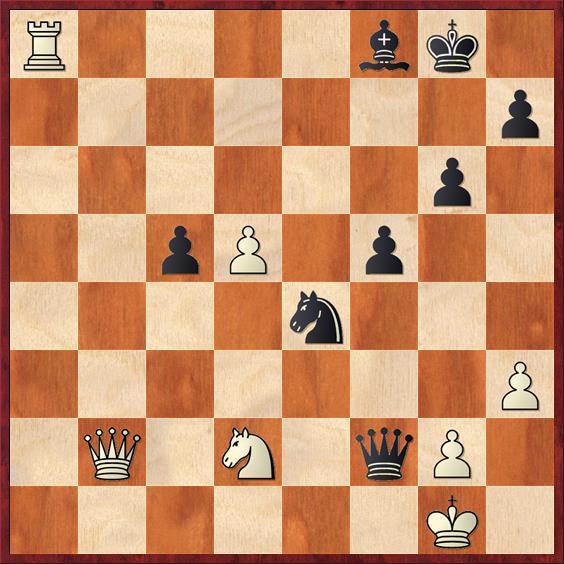

Position after 27. Qxd3. Black to move.

Position after 27. Qxd3. Black to move.

FEN: 5rk1/1q4bp/3B2p1/2pP1p2/b1n5/Rp1Q3P/1P3PP1/4RNK1 b – – 0 27

If ever there was an Emory Tate position, this is it. A position of bewildering complexity, with pieces hanging all over the board. Once again, the move that Emory chose did not pass computer scrutiny, although it looks natural enough. Emory, too, was only human — just a better, braver type of human than most of us.

27. … Nxb2? After this move, Rybka says that White equalizes with 28. Qe2! The idea is to get the counterplay on the e-file going as quickly as possible. It turns out that Black cannot save both the exchange and the c-pawn, because if 28. … Rc8 White has the remarkable 29. Qe6+ Kh8 30. Bxc5! Rxc5 31. Rxa4! The weakness of Black’s back rank means that he cannot recapture.

Well, what can I say? I didn’t see it. Most humans wouldn’t see it either. I played the more passive 28. Qb1?, Emory played 28. … Nc4 29. Rxa4 Nxd6, and the advantage swung back in his favor.

Let’s fast-forward to the position where the game was truly decided.

Position after 35. Rxb2. Black to play.

Position after 35. Rxb2. Black to play.

FEN: 1r3bk1/7p/3n2p1/R1pP1p2/8/Q6P/1R1NqPP1/6K1 b – – 0 35

Here it’s Black to play and win. I mean that seriously. Black has one move that, according to Rybka, gives him a four-pawn advantage. Any other move is only equal.

If only Emory had played the right move here, I could present this game as a true Emory Tate brilliancy. But he didn’t. The correct move is 35. … Qe1+! It’s a beautiful little twist. If 36. Nf1 Black wins a rook because White’s queen is overloaded: 36. … Rxb2 37. Qxb2 Qxa5. Or if 36. Kh2, Black wins a rook with a fork: 36. Qe5+! What a sweet little combination out of nowhere!

Instead, Emory played what seemed to be a crushing combination: 35. … Rxb2?? 36. Qxb2 Ne4. It’s curtains for White, right? If you defend the knight, Black is going to checkmate you after … Qxf2+.

The trouble with Emory’s combination is that he’s allowed White too much counterplay. In desperation I played the saving move: 37. Ra8! Qxf2+. And now comes the moment I will ever regret.

Position after 37. … Qxf2+. White to move.

Position after 37. … Qxf2+. White to move.

FEN: R4bk1/7p/6p1/2pP1p2/4n3/7P/1Q1N1qP1/6K1 w – – 0 38

Which is the right square for White’s king? h2 or h1? You have ten seconds to decide.

With literally only seconds left to play three moves, I chose the wrong square. I played 38. Kh2?? and threw away a hard-fought draw. The reason this is a blunder is that after 38. … Nxd2! I could not reply 39. Qf6 because of 39. … Nf3+! 40. Kh1 Qg1 mate. If I had played my king to h1, first of all, Nf3 wouldn’t have been check, and secondly my g-pawn wouldn’t have been pinned.

Instead I played 39. Rxf8+ Kxf8 40. Qf6+, but after 40. … Kg8 it’s easy to see that Black’s king can escape the checks by running to h6. I resigned three moves later.

Amazingly, after 38. Kh1!! Black would have had no way to win. (I’ve checked this on the computer, of course.) The basic point is that if Black moves his knight, he has no good defense to Qf6; he has to either checkmate White or else get his queen to h6, which is only good for a draw. And after 38. Kh1 there are no checkmates. Black can’t seem to “lose a tempo” to set up his desired … Nf3+. The other very important point after 38. Kh1 is that if Black plays 38. … Qxd2 39. Qxd2 Nxd2 it’s only a draw because he has to sacrifice his bishop to stop the d-pawn: 40. d6 Kf7 41. d7 Be7 42. d8Q Bxd8 43. Rxd8 =.

What a game! Of course, it’s far from perfect. Tate made significant mistakes on move 27 and on move 35, and in some sense the deciding factor in the game was my time trouble (always my Achilles’ heel). Nevertheless, it’s a beautiful example of Tate’s style of play. In the final analysis he completely deserved to win. If you play this way, putting extreme pressure on your opponent, you will win nine times out of ten — even if “objectively” your opponent could have saved himself.

It’s so hard to believe he’s gone. I’m glad that he didn’t suffer too long. Emory Tate, truly an American classic.

{ 7 comments… read them below or add one }

Nice tribute. I, too, was stunned to see the news about Emory Sunday morning. Although we were on friendly terms, I sadly never got to know him that well. We played twice in classical tournaments (and maybe twice in a blitz event I think) and my only score – a draw at the 2005 Louisville Open – is still one of my proudest results as I am in the low-expert rating area. I always envied his irrepressible personality and the gusto with which he played – and analyzed. R.I.P.

Man, Dana, I haven’t read your post yet, but hope to do so ASAP when I get home today. From the quick sound of it, the loss of ET was a huge blow to American chess and CA chess in particular. But isn’t this how we all secretly hope to go, OTB?

My sympathies to Tate’s family.

Wasn’t Tate profiled in a non-fiction chess book at one point? I need to go back and look at my library. I searched Amazon, and apparently Tate did not write any books of his own, a shame. Never met the guy in person, but he seems to have been quite the charismatic master teacher and master player. Let’s provide Emory Tate with the fine final post-mortem he deserves.

Hi Howard, I think that you might be thinking of “The Chess Artist,” which profiled Glenn Umstead. Both are (or were) African-American chess masters, but Emory Tate was a much bigger deal in the chess world. He was an International Master, the second-highest title after International Grandmaster. Umstead is “just” a national master (the same level as me).

Also, I would venture to say that Tate made a bigger impression than most IM’s because of his uncompromising attacking style, which enabled him to win numerous games against GM’s even though he never attained the grandmaster level himself.

The USCF news page has no mention of IM Tate’s passing. Shame.

USCF has an article up now, with some nice tributes and several games.

Actually, Dana, in the “Chess Artist” by JC Hallman, the book you refer to, you’re right, Umstead is prominently featured as a main protagonist; however, Emory Tate plays a wonderful cameo on pp. 232-233! I just searched for “Tate” in Amazon’s Search Inside the Book tool. Go check it out. Hallman provides a rich and colorful description of how Tate must have analyzed and kibbitzed. Unfortunately I’m at work and don’t have time to retype two pages of text. Amazon does not allow copy and paste from their search tool. But Hallman’s description is so rich that it might be worth duplicating here or making a separate post for it — wonderful stuff.

Speaking of “The Chess Artist,” after I finished reading that book I was so impressed by the writing that I contacted both Hallman and Umstead. (I think I might have even interviewed Hallman.) Umstead got back to me and sent me a whole set of Fischer documentary DVDs he was working on, along with his business card and some other chess stuff. This was about nine or ten years ago. Then one day, about two months ago, I’m working on a chess exercise at my local Panera Bread. A black guy [color is actually relevant here for the story] comes up to me and starts chatting about my exercise, asks what I’m doing, says he plays online, etc. We keep the conversation going, and he says his cousin, the person who taught him how to play and with whom he played with as a kid, is a chess master down in Atlantic City. Ding! So of course I remember Umstead from the “Chess Artist.” How many black chess masters live in Atlantic City? So I say, “I know your cousin’s name. It is Glenn Umstead.” The guy freaked out out! How does some random guy in a restaurant know his cousin’s name? Apparently the book is so old now that the guy forgot it was written. So I told him the same story I just wrote here, about the DVDs, etc. Small chess world.

So go check out pp.232-233 of “The Chess Artist” for a great tribute to IM Emory Tate.

Chessbase has an article now

http://en.chessbase.com/post/rest-in-power-emory-tate-1958-2015