So I won a Matrix chess game against Shredder on my computer (game/10, I get one time-out of arbitrary length, Shredder’s rating was set for this game at 2298) and was feeling pretty good about myself until I went over it with Rybka. Ugh!

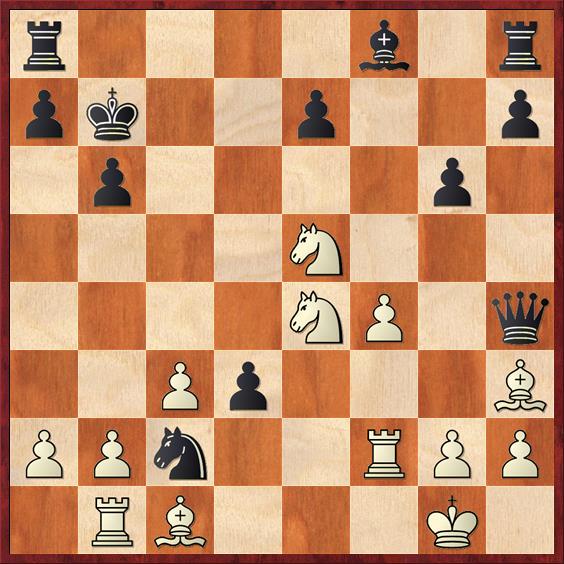

Position after 21. … d3. White to move.

Position after 21. … d3. White to move.

FEN: r4b1r/pk2p2p/1p4p1/4N3/4NP1q/2Pp3B/PPn2RPP/1RB3K1 w – – 0 22

Quiz position 1: What is White’s best move?

This position came from my favorite opening in chess, the Bryntse Gambit queen-sacrifice variation (1. e4 c5 2. f4 d5 3. Nf3 de 4. Ng5 Nf6 5. Bc4 Bg4?! 6. Qxg4!!) As always in the Bryntse Gambit, the position is extraordinarily complex. White has only two pieces for a queen, but both Black’s queen on h4 and knight on c2 are in great danger of being trapped.

At this point I was going to play 22. Nxd3 until I saw the computer had laid a trap for me: 22. Nxd3?? Rd8! 23. Ne5 Rd1+ 24. Rf1 Rxf1+ 25. Kxf1 Qe1 mate. Yikes! I decided I’d better take my time-out and regroup.

The first two candidate moves that I looked at were 22. Be6 and 22. Bd2. They both make a certain amount of sense. The one huge flaw in my position, as the above line shows, is the weakness of my back rank. 22. Bd2 takes care of that, and threatens to capture on d3. But it’s kind of a slow move. I thought that Black could get a very reasonable game, maybe even with chances for an advantage, by giving back an exchange: 22. Bd2 Rd8 23. Nf7 Bg7 24. Nxh8 Bxh8. It’s not clear that White will ever be able to dislodge the pawn on d3 or the knight on c2, and the longer they stay there the more they become a strength for Black rather than a weakness.

Then, before I could seriously analyze 22. Be6, a new idea hit me: What about 22. Bg4? This move seemed to combine a number of wonderful features. It moves the bishop to a protected square, so g3 becomes a threat. It takes away a flight square from Black’s queen, which makes the threat to trap Black’s queen very serious. (For example, Black cannot reply 22. … h5 or 22. … Bg7 because his queen gets trapped.) Also, 22. Bg4 defends d1, so that Nxd3 is now a more serious threat. Finally, it repositions the bishop so that Bf3 becomes a possibility, eyeing Black’s king.

This is the type of move I love to find in Matrix chess — a move that was not even on my radar screen before I took the time-out.

Unfortunately, I soon realized that Black’s best answer to 22. Bg4 is 22. … e6, preparing a new flight path for Black’s queen. After 23. g3 Qe7 or 23. … Qd8 there are definite practical problems. For example, on 23. … Qd8 I wanted to play 24. Rd2 and win the d-pawn But this fails on account of 24. … Ne1 25. Kf1 Qd5! White’s pieces are all tangled up, and Black wins after, say, 26. Kxe1 Qxe4+ 27. Kf2 Bc5+.

Then I started thinking about ways to improve this line, and it occurred to me that there was really no need to spend a tempo with 23. g3. Why not just put my bishop on the main diagonal right away? After 23. Bf3!? I’m essentially a tempo ahead of a lot of the lines I had just analyzed. The trouble now is that Black might play 23. … Ne1 and exchange off my bishop. But I realized that I could avoid this by a tactical sequence: 24. Nd6+ Kb8 25. Nc6+ Kc7 26. Nb5+ Kb7 27. Be4, and I felt good about White’s chances. This seemed like a good use of my time-out: I would play a move (22. Bg4) that I hadn’t been considering before, and follow it up with a maneuver (moves 24-7) I wouldn’t have been able to calculate with confidence in a speed game.

But I didn’t want to play 22. Bg4 without looking at all of my candidate moves. So I set up the position after 22. Be6! and realized there were some very good things about it, too. First, 22. … Rd8? is now completely out of the question because White wins a full rook with 23. g3 Qh6 24. Nf7 followed by Nxd8+. I quickly reached the conclusion that Black’s best reply was 22. … Bg7, trying to exchange off the knight on e5. But now I can play the ultra-sharp 23. g3 Qh6 (forced, because … Qh5 gets the queen trapped after Bg4) 24. f5!?!

The position after 24. f5 is absolutely insanely complicated. White now has a hanging knight on e5 and the back rank is still undefended. On the other hand, Black’s queen is in a pickle. Perhaps Black should look for a way to give it back for two pieces, or perhaps he should play 24. … Qh3, when I couldn’t quite see a way to trap the queen. In the final analysis I couldn’t reach a clear assessment and I was worried that this was exactly the sort of position where a computer would find a miraculous tactical resource that I couldn’t see.

So now I still had a dilemma! I had two candidate moves. One, 22. Bg4, looked solid but maybe a little bit too slow. The other, 22. Be6, is essentially an attempt to win the game immediately, but it might backfire and if it does, it will probably backfire in a big way.

I finally decided that this is supposed to be a training game for real, tournament chess. In a real game it would be folly to blast the position open when I have pieces hanging, pieces undeveloped, and my king sitting on a very insecure back rank. Good players shore up their weaknesses and eliminate counterplay before they launch an all-out attack. So I chose 22. Bg4?.

There you have it, my complete thought process over probably three hours of analysis, longer than I would ever be able to analyze a position in a real over-the-board game. Now tell me: What did I do wrong?

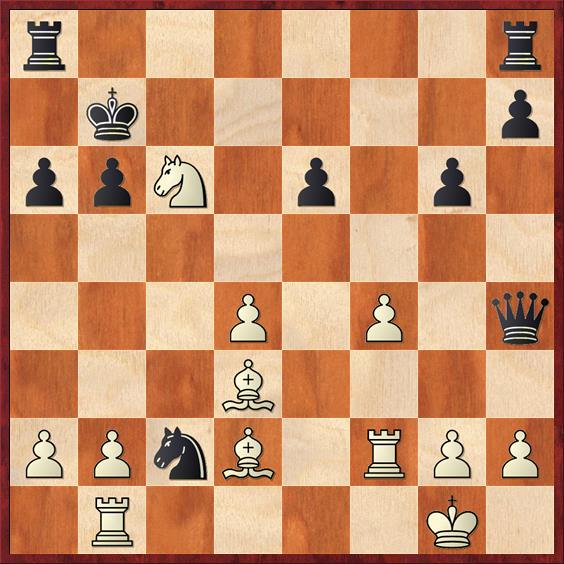

Before I answer this question, I’ll show you how the rest of the game went. As I said at the beginning, I won, so at first I was under the impression that my 22nd move was a good one. Shredder did in fact choose the line I had expected: 22. … e6 23. Bf3!? Ne1 24. Nd6+ Kb8 25. Nc6+ Kc7 26. Nb5+ but now it deviated with 26. … Kc8, probably a slight improvement over the move 26. … Kb7 I had considered in my analysis. The game continued 27. Be4 Bc5 28. Nbd4 a6 (a move I don’t quite understand) 29. Bd2 Nc2 30. Bxd3 and now instead of 30. … Nxd4, which completely equalizes, Shredder played 30. … Bxd4??, which loses. After 31. cd Kb7 White has a nice winning trick. Do you see it?

Position after 31. … Kb7. White to move.

Position after 31. … Kb7. White to move.

FEN: r6r/1k5p/ppN1p1p1/8/3P1P1q/3B4/PPnB1RPP/1R4K1 w – – 0 32

Quiz position 2.

Okay, here are the answers.

Answer to quiz position 1: The failure in my thought process was that I did not consider enough candidate moves. This is a flaw that Mike Splane has pointed out more than once.

In three hours of analysis, I never once considered the move 22. Ng5!, which is completely decisive. It’s hard to say why I missed it, because I certainly looked at the possibility a move or two later. Well, one reason is that I completely missed the fact that it defends the bishop on h3, so that g3 becomes a threat. I was very keen on playing g3, which is why I looked so strongly at Bg4 and Be6, but I somehow missed the idea of defending the bishop instead of moving it. Now 22. … e6 is too slow. White plays 23. g3 Qh6 24. Bg2+ and wins ridiculous amounts of material, either a rook outright or two exchanges after 24. … Kb8 25. Ngf7. According to Rybka, Black’s best reply is 22. … Bg7, but White is still winning (+2 pawns) after 23. g3 and either (a) 23. … Qh6 24. Nef7 Qh5 25. Bg2+ Kc7 26. Bf3! (cute!!) or (b) 23. … Qxg5 24. hg Bxe5 25. Bg2+ and White emerges from the complications with an extra exchange.

Answer to quiz position 2: Don’t settle for winning the exchange with 32. Bxc2? Kxc6 33. Be4+ followed by Bxa8. According to Rybka, this endgame (Q vs, R+B+P) is better for Black. I think the computer is right, because my bishop does not make any threats. It’s a purely defensive piece. Maybe White can draw, but it will be an uphill battle.

Instead, the winning move is 32. Be4!, which wins a whole piece after 32. … Rac8 33. Nb4+ Ka7 34. Nxc2. Even though White has only a slight edge in material (2B + N + P vs. Q), his advantage in position is overwhelming. The two bishops are so much better than the one bishop in the previous line that it’s not funny. This is a pretty common theme in the Bryntse Gambit. See, for example, my game against Sergei Kudrin last fall, where he tried over and over to get me to trade off one of my bishops for a rook, and I refused to do it.

What did I learn from this game? (1) I’m still missing good candidate moves. (2) One reason might be falling in love with a move too quickly. I like the fact that I found a move, 22. Bg4, that was not on my original list of candidate moves — but then I fell in love with it and stopped looking for other unsuspected possibilities. (3) Although Rybka says 22. Be6 is better than 22. Bg4, I don’t think I should beat myself up too much over it. I think I had good and valid reasons to play 22. Bg4. The real failure was not seeing 22. Ng5. (4) Prioritize your targets. The move 22. Bg4 was mostly directed toward winning the d3 pawn and the knight. It allows the Black queen to escape rather easily after 22. … e6. The move 22. Ng5 raises the stakes dramatically — the queen’s retreat is cut off and Black has to pay dearly to get her out.

When you attack a high-priority target such as the king or queen, sometimes the lower-priority targets fall of their own accord. Reach for an apple and you might get an apple, if you even get that much. Shake the whole tree and the apples come to you.