As I promised, here is my game from round five of the Thanksgiving Festival. My opponent was Paul Richter, a class A player who looks to be 13 years old or so (but we know how bad I am at estimating ages). It’s just the sort of game that I love, with pieces flying everywhere.

I thought I played really well, but looking at it quickly on the computer I see that there were two places where I missed very strong moves — including one that would have basically ended the game. In both cases they were moves I didn’t even think about, so the lesson I need to take from this game is, “When you see a good move, stop and see if you can find a better one.” Nevertheless, I’m still happy with the game and especially with the winning combination.

Paul Richter — Dana Mackenzie

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4 ed 4. Bc4 Nf6 5. e5 d5 6. Bb5 …

This is a variation of the Two Knights Defense that I lectured about for ChessLecture last year. Although it’s technically known as the Modern Variation, I suggested that it should be called the Nimzo-Two Knights, because White plans a blockading strategy that is very much in keeping with Nimzovich’s principles. Ideally, he will cripple Black’s queenside pawn structure in such a way that Black’s 4-on-3 majority is neutralized, and then White’s 4-on-3 kingside majority will be decisive.

In the past I have struggled against this variation, but in this game I tried a new idea that I came up in a blitz game a few years ago.

6. … Nd7!? 7. O-O Be7 8. Bxc6 bc 9. Nxd4 Nb8!

A startling idea. Black has taken two tempi to undevelop his king knight and put it on the queen knight’s original square! What does Black gain as a result? In a word, flexibility. In the normal lines, his queen bishop goes to d7 and is hemmed in by the pawns. In this line, Black has kept alive the possibility for the bishop to develop either on the c8-h3 diagonal or on the c8-a6 diagonal.

10. f4?! …

Already a slight error. When I analyzed this variation a few years ago, I thought that this move was almost automatic. But my master friend, Gjon Feinstein, called this assumption into question and pointed out that White has better things that he can do with his tempo, such as 10. c4 or 10. Nc3. The computer confirms that both of these are better options.

The move 10. f4 here is quite reminiscent of the same move in the Bird Variation of the Ruy Lopez, which I analyzed in Bird by Bird, Part 3A. Here, as there, it is very tempting for White to launch a big kingside pawn storm because of all the empty space that Black has left on the kingside. But here, as in that variation, the pawn storm is sort of a red herring. With White’s queenside still undeveloped, it’s premature, and it’s also out of keeping with the Nimzovichian spirit of this variation for White. Remember that Nimzovich would first paralyze his opponent with prophylactic and blockading moves, then launch his attack.

10. … c5 11. Ne2 f5

I debated long and hard between this move and 11. … Nc6. I liked 11. … Nc6 because it is a developing move, but at this point I still wasn’t sure whether I wanted to put my knight on c6 or a pawn on c6. Also, 11. … f5 really stops the whole pawn storm idea in its tracks.

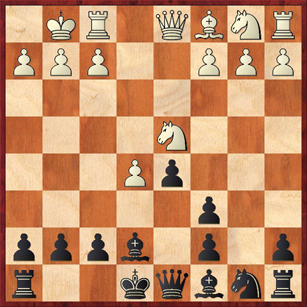

12. ef Bxf6 13. Ng3 O-O 14. Nh5? …

This definitely looks like a kid’s move — he’s wasting so much time with this knight and neglecting the rest of his pieces. I was sure at this point that I stood better, but unfortunately I relaxed a little bit and didn’t really look for the most forceful way to take advantage of his mistake.

14. … Bd4+ 15. Kh1 g6?!

I played this move almost automatically; I was happy to chase his knight away and simultaneously provide a flight square for my bishop. But the computer says 15. … Qh4! is much better, threatening 16. … Bg4 and really putting White in critical danger already. The first of two big missed opportunities for me.

16. c3 Bh8 17. Ng3 Nc6 18. Na3 Rb8 19. Qc2 Ne7 20. Be3 Qd6 21. Rad1 Qc6 22. Qf2 …

It looks as if White is winning a pawn, because c5 is indefensible and the a7 pawn hangs if Black pushes to c4. But I had great faith in the activity of my pieces, which are so beautifully posted — both rooks on open files, the bishops sitting on 3 (!) important diagonals, and the knight poised to jump to f5 or d5. I was sure that there must be a way either to get compensation for the lost pawn or to simply win the pawn back — it was just a matter of figuring out the right way.

22. … d4!

My second-favorite move of this game. It simultaneously bottles up White’s bishop and sets Black’s knight free. A pawn is a small price to pay for these advantages.

23. cd Nd5! 24. dc Nxe3 25. Qxe3 Rxb2 26. Rf2? …

It turns out that 26. Rd2 would have been better, although Black then easily wins back the pawn with 26. … Rxd2 27. Qxd2 Qxc5.

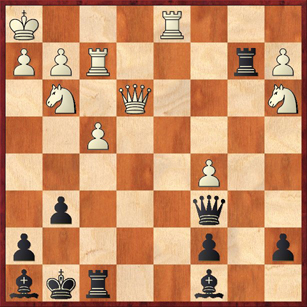

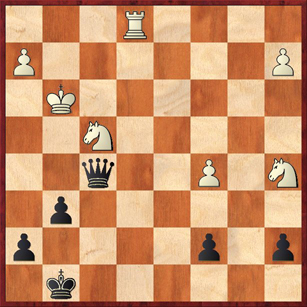

Black to play and win.

The trouble with tournament chess is that you don’t have someone tapping you on the shoulder and saying “Black to play and win.” In this position I was definitely feeling some time pressure. It wasn’t bad pressure, but still I had to make 5 moves in 5 or 6 minutes. And this move looked like one that I could play automatically, so I played the rook trade after only a few seconds of thought.

The first moral is, don’t get low on time. But the second, and more useful, moral is to beware of thinking of any move as “obvious.” There are no automatic moves in chess. Even if you have only a few seconds, use those few seconds to check for the move that comes out of left field, such as zwischenzugs (in-between moves) or moves played in the opposite order from what you would expect. I should know this; I’ve lectured on both of those topics for ChessLecture. But I failed to apply the principle here.

Have you found the correct move? It’s 26. … Re8!, which basically ends the game on the spot. Black’s pieces control so many squares that the White queen has only one square to go where it will still protect the f2 rook: 27. Qf3. And then, rather fortuitously, Black wins the exchange with a nice skewer: 27. … Qxf3 28. Rxf3 Bg4!

Well, that would have been a great finish, but the way that the game ended was pretty good, also.

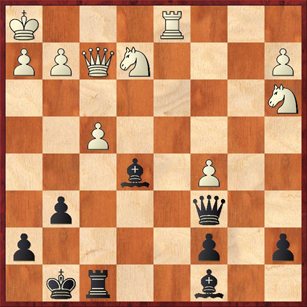

I played 26. … Rxf2? 27. Qxf2 Be5! 28. Ne2 and now I faced another decision, which used up most of my remaining time.

Here I saw 28. … Qa4, which was my original intention, but I couldn’t work it out to a clear win for Black. Then I remembered another old chess maxim: The threat is stronger than the execution. In many cases, if you have one threat, it is best to build up the pressure, and add more threats. Against human opponents this is especially effective, because you give them more things to worry about and more things to keep track of, and they are more likely to make a mistake. Against computers, this psychological aspect disappears, of course.

So I played 28. … Bb7, a move that ramps up the pressure against White. Now he has to worry about checkmate on g2, and therefore … Bxf4 is now a bona fide threat as well. Meanwhile, the move … Qa4 is kept in reserve for future use.

The computer says that 28. … Qa4 was better, but I refuse to call 28. … Bb7 a mistake. The remaining moves of the game show that my decision was fully justified.

29. Nc4 Bxf4 30. Na5? …

Better was 30. Nxf4 Rxf4 31. Rd8+ Kg7 32. Qb2+ Qf6 (this is as far as I got in my time-pressure analysis) 33. Rd7+ Kf8 (or g8) 34. Qxf6+ Rxf6 35. Kg1 Rf7, with a drawish endgame. But I’m not sure that the endgame is dead drawn — just drawish.

30. … Qa4!

What a great move to have in reserve on the last move of the time control! I was really glad now that I hadn’t played it on move 28.

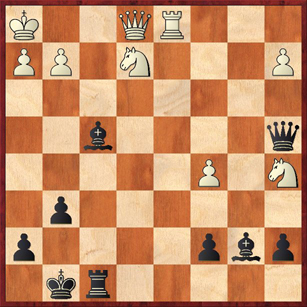

31. Qe1 …

This seemingly holds everything together, but …

Black to play and win (again!).

Now, of course, I had all the time that I wanted to decide on my next move (the second time control was game/60). I mentioned earlier that the trouble with chess is that you don’t have someone tapping you on the shoulder and saying, “Black to play and win.” But this position is an exception. It looks exactly like something that came out of a book: the two Black bishops bearing down on the kingside, White’s pieces clustered in an ineffective lump, all except for the wandering knight on a5. If ever a position was ripe for a sacrifice, this is it.

31. … Bxg2+!

This is my favorite move of the game.

32. Kxg2 Qe4+ 33. Kh3 Re8

The computer likes 33. … Qf5+ better, but it’s just a matter of taste.

34. Nxf4 Qf5+ 35. Kg3 Rxe1 36. Rxe1 …

This is as far as I analyzed on move 31. White is still nominally ahead in material (R+2N versus Q+P) but White’s pieces are so scattered and uncoordinated that I felt certain I would be able to win one of the knights. And, in fact, it didn’t take long to work out a way to do just that.

36. … Qg5+ 37. Kf3 Qf6!

Threatening both … Qc3+, which forks everything, and … g5, which wins the f4 knight due to the pin on the f-file. There’s nothing that White can do. The rest of the game requires no comment.

38. Kg4 h5+ 39. Kf3 g5 40. Re4 gf 41. Nc4 Qh4 42. Rxf4 Qxh2 43. a3 Qh1+ 44. Kg3 Qg1+ 45. Kh4 Qxc5 46. Kg3 Kg7 47. Kh3 Kg6 48. Rh4 Kg5 49. Re4 Qf5+ 0-1

Aside from the missed win on move 26, a very harmonious game where everything flowed from the great activity of Black’s pieces.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Great game! 🙂

I remember that saying wasn’t it when these two chess players were playing but one of them only agreed to play if the other didn’t smoke his cigars, and so in the middle of the game the second player lay out two cigars and then the first player said “hey I told you not to” and the second player said I’m not I’m just threatening to” and then the the first player said “ah yes but the threat is greater than the execution”. At least that is how I learned it.:)