I wrote recently about my new training idea: playing 10-minute games against the computer, with the condition that I can take one “time-out” of unlimited duration during the game to analyze the position better. One of my readers, I forget whether it was here or on Facebook, said that it reminded him of “The Matrix,” where Neo can slow down time as much as he wants during battle.

However, I’m not as powerful as Neo, and I can only stop time once. I have found this to be a challenging training technique, which has given me lots of fascinating positions to analyze. I’ve done it about six times now. The trick is to find the right time for a time-out, when there are really substantive decisions to make that can affect the outcome. Too early and you may not really change the course of the game. Too late and the battle may already be over.

Here is one case where I called time-out at just the right time. I am playing Black against Shredder, which is set at a rating of 2165.

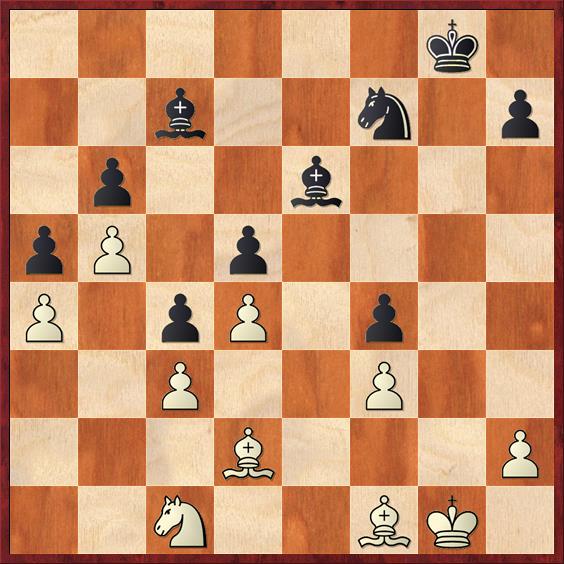

Position after 33. Bd2. Black to move.

Position after 33. Bd2. Black to move.

FEN: 6k1/2b2n1p/1p2b3/pP1p4/P1pP1p2/2P2P2/3B3P/2N2BK1 b – – 0 33

This game, which came out of a Sokolsky’s Opening (1. b4), seemed for a long time to be heading towards a draw because of the symmetric pawn formation. However, the computer allowed me to push my pawn to f4, which exerts a huge cramping effect on White’s position. I called a time-out here because I had a sense that Black was on the verge of something good. White’s pieces are all tangled up and stepping on each other’s toes, and Black controls all the key lines of attack. Specifically, I had two candidate moves, 33. … Bf5 and 33. … Ng5. Although I was leaning toward the former, I wanted to think about it and get it right.

Superficially 33. … Bf5 looks good because it wins material. However, it also allows White’s pieces to become active, and that is its main problem. The position is all about piece coordination, and I want my pieces to continue to work together better than the computer’s.

Indeed, after 33. … Bf5 34. Ne2! Bc2 35. Nxf4! the threat of Nxd5 and Bxc4 is too strong, so Black must take the knight. But then 35. … Bxf4 36. Bxf4 Bxa4 37. Bc7 Bxb5 38. Bxb6 a4 39. Bc5 stops the a-pawn and leads to a position that I think White can hold with no trouble. Also, after 33. … Bf5 34. Ne2 it’s too late for 34. … Ng5, this time because of 35. Bxf4! At first I thought 35. … Ne6 might be the solution, but then White stuns Black with 36. Bxc7 Nxc7 37. Nf4 Bc2 38. Nxd5! Nxd5 39. Bxc4 and the pin is lethal.

There are other variations to consider, but the above variation especially made me feel as if I was playing the moves in the wrong order. It’s extremely likely that I would have overlooked the sham sac at d5 in a blitz game, and maybe even in a tournament game.

So, let’s take a look at the alternative, 33. … Ng5! This is a key move because it takes advantage of the awkward placement of White’s king and bishop on d2. I would even venture to suggest a rule:

When you have two alternatives, one that strengthens your position in a “generic” way and the other that takes advantage of some special feature in the position to strengthen your position, the second is often stronger. The reason is that the “generic” strengthening move will probably continue to be there, but the “special” move may only be available one time.

Now, again, let’s go from the general to the specific. White has to defend the f-pawn, and I considered the main line to be 34. Be2, with the idea of transferring the bishop to d1 and holding the queenside pawns. Now is the right moment for 34. … Bf5!, which both threatens … Bc2 and frees e6 for the knight. A very critical point here is that White cannot play his intended 35. Bd1? because of the stunning 35. … Bc2!! 36. Bxc2 Nxf3+ 37. Kf2 Nxd2. Even though the knight at d2 may seem to be in a dangerous spot, it’s actually quite hard for White to evict him, and further analysis convinced me that Black has simply won a pawn with a big advantage.

Again, chances of finding this in a blitz game: Near zero. That’s why it was a perfect time for a time-out.

Unfortunately, White can improve with 35. h4!, driving the knight away before it can play the crushing fork on f3. In fact, at first I thought that this just led to total boring equality after 35. … Ne6 36. Bd1. All of White’s weaknesses seem to be defended. How can Black hope to win this game?

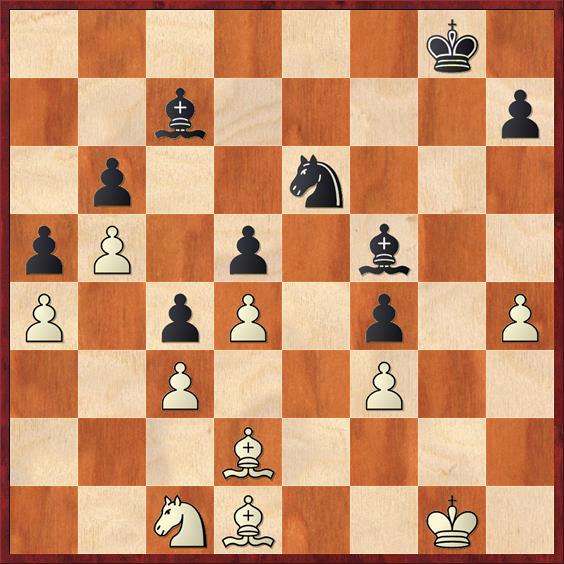

Position after 36. Bd1 (analysis).

Position after 36. Bd1 (analysis).

FEN: 6k1/2b4p/1p2n3/pP1p1b2/P1pP1p1P/2P2P2/3B4/2NB2K1 b – – 0 36

In fact, Black is winning a pawn by force here. If you aren’t sure how, consider the fact that all of White’s pieces are completely tied down. So this is a position where Black has all the time in the world. Second, think about one of the Mike Splane questions: What piece in Black’s position is not doing anything, and how can we give it something to do? And the biggest hint of all: don’t forget that in the endgame, the king counts as a piece!

That’s right, after 36. … Kg7! White can do nothing about Black’s plan of marching the king to h5 and taking the h-pawn. For example, if 37. Ne2 Kg6 38. Kg2 Kh5 39. Be1 Nf8 40. Bd2 Ng6, and the pawn falls.

That doesn’t mean the game is over, but I think that Black would have extremely good winning chances here. So I was convinced that 33. … Ng5! was the right move. Notice how beautifully all of Black’s pieces coordinated in this variation, including the king. And notice how White never had an iota of counterplay.

In the game, the computer surprised me by responding to 33. … Ng5! with 34. Bg2. This signals that White is willing to abandon his queenside pawns to the fates. Of course I had also looked at this move during my “time-out,” but it looked to me as if White is giving up too much. The main challenge for Black is to avoid bishops of opposite color endgames, which might give White a chance to draw.

Thus the game continued 34. … Bf5 35. Ne2 Ne6 36. Kf1 (clearly White has no plan) 36. … Kf7 37. h4 Kf6 38. Kf2 Bc2 39. Bh3 Bxa4 40. Bxe6 Kxe6 41. Nxf4+ Kd6 (as mentioned above, 41. … Bxf4 would give White very good drawing chances because of OCB’s) 42. Nh5 Bxb5 43. Nf6 Bd8 44. Bg5 (diagram).

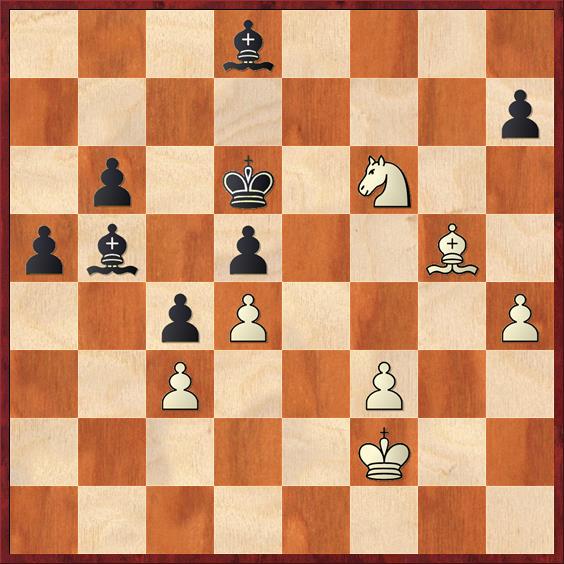

Position after 44. Bg5. Black to move.

Position after 44. Bg5. Black to move.

FEN: 3b4/7p/1p1k1N2/pb1p2B1/2pP3P/2P2P2/5K2/8 b – – 0 44

For a moment I thought I might have screwed up here, because 44. … Bxf6? 45. Bxf6 a4 46. Bg5 a3 47. Bc1 a2 48. Bb2 gets the bishop back just in the nick of time to stop the pawn. However, it didn’t take me long to realize that 44. … h6! clinches the deal. The computer played 45. Ne8+ Kd7! (Not 45. … Bxe8?? 46. Bxd8 with a draw) 46. Bxd8 Kxd8 47. Nd6 Be8 48. Nf5 h5 49. Ne3 Bf7 and whew! We can finally exhale. Sixteen moves after the time-out, Black has consolidated his extra pawn and the march of the a- and b-pawns will inevitably win. The finish went 50. Kg3 b5 51. Nc2 Ke7 52. Kf4 Kf6 53. Kg3 Bg6 54. Ne3 Ke6 55. Ng2 b4 56. Nf4+ Kd6 (go ahead! take my bishop!) 57. cb ab 58. Kf2 b3 59. Ne2 b2 60. Nc3 b1Q 61. Nxb1 Bxb1 and the rest is academic.

Next time perhaps I’ll show you an example where my time-out did not go so well.