Last time I wrote about the most popular opening variations, by ECO code. I also wrote about the best ones for White/worst ones for Black, by ECO code. As I expected this generated a bit of a reaction, especially from proponents of the Dutch Defense. Their comments raise some good issues about how to interpret these statistics, and I’ll talk a little bit more about that at the end. But for now, let’s carry on! Today it will be my turn to eat a little crow, because there is some bad news about my own favorite openings.

Just as a reminder, I’m splitting each category up into two subcategories — “common variations” (played in more than 1 out of every 1000 games) and “uncommon variations” (played in less than 1 of every 1000).

Best ECO Code for Black — Common Variations

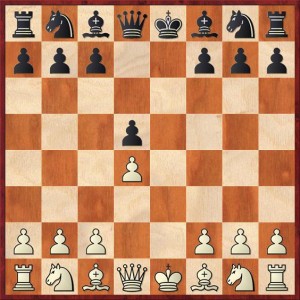

To me, this is already quite a surprise. The best variation for Black/worst variation for White is the Richter-Veresov Attack. The surprise is that (as I pointed out in Part One of this series) White tends to score better in d-pawn openings than in e-pawn. So White must be doing something really wrong to forfeit not only his normal opening advantage but also his extra advantage due to 1. d4.

It would be interesting to drill deeper and see what lines are causing White the most trouble here. I’ve had good results with 3. … Nbd7 4. Qd3 c5, with a draw and a win as Black. All three of White’s main options score very badly in ChessBase: 5.e4 (28.3 percent), 5. dc (21.1 percent! Truly awful!) and 5. O-O-O (44.1 percent). However, these results are based on quite small sample sizes.

Expanding our focus, here are the top five variations for Black:

- D01 (Richter-Veresov) — 54.8 percent

- B26 (Closed Sicilian 1. e4 c5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. g3 g6 4. Bg2 Bg7 5. d3 d6 6. Be3) — 54.0

- B25 (Closed Sicilian, same line as above without 6. Be3) — 53.7

- B44 (Paulsen, including Szen-Kasparov Gambit) — 53.3

- B21 (Smith-Morra and Grand Prix Sicilians) — 53.1

Some really interesting openings here. First, notice that all of them, except for the anomaly of the Veresov Attack, are Sicilians. So any readers who are Sicilian players should be very happy. The closed Sicilians B25 and B26 (for all practical purposes these two variations are the same) pose little danger to Black. The Smith-Morra looks like just a loss of a pawn, as Bent Larsen famously remarked in the San Antonio 1972 tournament book. Alas, my Grand Prix Sicilian (the line I usually play as White against the Sicilian) also looks like a grand faux pas.

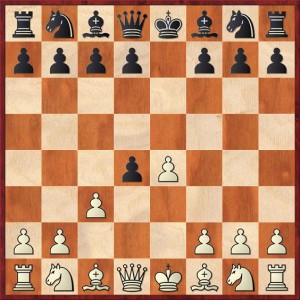

One entry I’m glad to see here is B44. I’d like to think that one reason for its success is the Szen-Kasparov Gambit, 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 e6 3. d4 cd 4. Nxd4 Nc6 5. Nb5 d6 6. c4 Nf6 7. N1c3 a6 8. Na3 d5!? I remember what a shock this was when Kasparov played it against Karpov in their 1985 World Championship match. It’s a rare game that altered both the course of chess history (Kasparov won the game and went on to win the match) and that altered opening theory.

Best ECO Code for Black — Uncommon Variations

Among the uncommon variations, the best for Black/worst for White is the Boleslavsky Variation of the Sicilian. This was again a surprise to me because I thought it was supposed to be a very respectable line for White. Didn’t Karpov play it a lot? But perhaps it’s just a little bit too unambitious for White. Some readers might wonder, “But what about the weak square on d5?” Well, one weakness isn’t enough to lose the game, and here it’s compensated by the fact that Black gets good active development for his pieces and White’s knights, on the other hand, look rather clumsy and ineffective. White would like to put a knight on d5, but lots of times it just gets exchanged, and if White recaptures with a pawn, then Black’s backward-pawn problem is solved.

The five best uncommon variations for Black are:

- B59 (Sicilian, Boleslavsky Variation with 7. Nb3) — 58.3 percent

- C39 (King’s Gambit Accepted with 4. h4) — 57.2

- C33 (King’s Gambit Accepted, Bishop’s Gambit) — 57.1

- E03 (Catalan with 5. Qa4+ Nbd7 6. Qxc4) — 57.1

- D04 (Colle Attack, 1. d4 d5 2. e3 Nf6 3. Nf3) and E24 (Nimzo-Indian Saemisch, uncommon lines) — both 54.3

Oh no! The King’s Gambit Accepted has a very sad track record when played by contemporary masters. Of course, Boris Spassky used the line 1. e4 e5 2. f4 ef 3. Nf3 g5 4. h4 (#2 on the above list) to beat Bobby Fischer at Mar del Plata 1960, a famous game that sent Fischer on a quest to find a “bust” for the King’s Gambit. Fischer eventually settled on 3. … d6, which is now called the Fischer Variation. But perhaps Fischer should have stuck to the line he played against Spassky! According to the statistics, it scores better for Black than the Fischer Variation.

The bad news for me is that the Bishop’s Gambit, one of my regular openings as White, comes in #3. So let’s see… my regular response to the Sicilian is the fifth-worst common opening variation for White. My regular response to double e-pawn is the third-worst uncommon opening variation for White. Both of them involve playing f4 on the second move. Time to re-evaluate the merits of f4? I know what Mike Splane would say. It’s a middle-game move that I’m playing in the opening.

I have no comments on #4 and #5 except that if you’re looking for more ways for White to give away his natural advantage after 1. d4, they are three options.

Most Drawish ECO Code — Common Variations

Pssst! Hey buddy! Wanna play a draw?

The Exchange Slav (D14) dominates this category like no variation dominates any other category. It’s a unique ECO code, a variation that is more about the players’ psychology than about chess. According to Rob Weir’s tables, this variation results in a draw 79.9 percent of the time in master play, and usually quickly. (The average number of moves is 25, about 8 less than any other variation.) If anything, I think that Weir’s statistics understate the extent to which these six moves serve as a wordless draw proposal. Weir removed all games of 10 moves or shorter from his database. When I look this position up on ChessBase, it looks as if at least 90 percent of the games are draws.

The top five drawing variations:

- D14 (Exchange Slav with … Nc6 and …Bf5): 79.9 percent draws

- D79 (Symmetric Grunfeld, 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 g6 3. g3 d5 4. Bg2 Bg7 5. Nf3 O-O 6. O-O c6 7. cd cd): 59.0

- C92 (Ruy Lopez, Flohr-Zaitsev Variation 9. … Bb7): 57.5

- D13 (Exchange Slav, not 5. Nc3 Nc6 6. Bf4 Bf5): 56.2

- B36 (Maroczy Bind, side variations): 56.1

Looking at this list, first of all, I didn’t even know it was possible to play the Grunfeld to draw (D79)! As usual, it’s mostly White’s fault; he is trying to play as much like an Exchange Slav as possible. Variation D13 inherits some of D14’s drawish tendencies, but still it’s a different animal. I actually play D13 to win, with 6. Qb3 on the sixth move instead of 6. Bf4. My idea is to try to force Black to play … e6 and imprison his queen bishop. Once Black gets that bishop out, any pretense of an advantage for White disappears. The other two, C92 and B36, are also not really drawing variations. They are variations where Black suffers for a long time and if he’s successful, then he gets a draw (and the statistics show that masters know how to do this). Really I wouldn’t consider any of these to be “drawing variations” except D14.

By the way, I want to point out one variation that isn’t on the list, or even anywhere close to it.

Superficially, the Exchange French (C01) looks a lot like the Exchange Slav, only with the e-file opened instead of the c-file. Yet this variation has only a 47.8 percent drawing rate. That’s a little higher than normal (39.3 percent is average), but nowhere near the stratospheric 80 percent drawing rate of the Exchange Slav. Why the big difference?

Well, here’s my take on it. In the Exchange Slav it’s very clear where Black wants to place his pieces, and it’s the mirror image of where White wants to. By contrast, in the Exchange French it’s not so clear. If White plays 4. Bd3, Black might want to play 4. … Nc6. If White plays 4. Nf3, Black might want to play 4. … Bf5. There are really lots of options available, and the imitation option is only one of them. It’s not even the most attractive option, because in fact Black scores greater than 50 percent in this variation!

This question came up in a comment on my first post in this series: How can a symmetric position be favorable to Black? The most likely reason is psychological. White may be playing the Exchange French out of fear (his opponent is rated much higher, so all he wants is a draw). This is supported by Weir’s statistics. When ratings are taken into account, White’s performance rating in C01 is actually better than his pre-game rating. It’s more or less the same as if he were playing level opposition and winning 52-53 percent of the time. For the same reason that White wants a draw, Black doesn’t want a draw. So C01 actually ends up being a fairly competitive opening.

Most Drawish ECO Code — Uncommon Variations

Because I’ve spent a long time talking about the common drawish openings, I will be very brief about the uncommon ones. Here they are:

- D56 (Queen’s Gambit Declined, 6. … h6 7. Bh4 but not Lasker or Tartakower): 65.3 percent draws

- D62 (QGD Rubinstein Variation 7. Qc2): 64.5

- D59 (QGD Tartakower Variation, with 8. cd Nxd5): 59.5

- D67 (QGD Orthodox Variation, side variations after 9. … Nxd5): 59.5

- E34 (Nimzo-Indian, 4. Qc2 d5): 57.3

This category is ruled by the Queen’s Gambit Declined. Again, I wouldn’t say these are drawing variations per se, they are variations where Black suffers for a long time but has a good chance of emerging with a draw when it’s all over. The fact that they are “uncommon” is only because the QGD has lost popularity compared with other Black defenses to 1. d4.

Least Drawish ECO Code — Common Variations

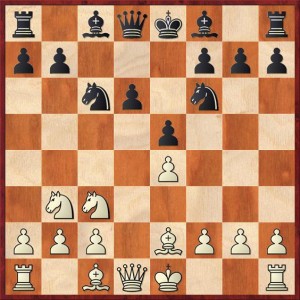

Unlike the last category, the Hall of Shame of chess openings, this category consists of the most honorable, “fightingest” opening variations in chess. And what better variation to start with than B89, the Velimirovic Attack in the Fischer-Sozin Variation of the Sicilian Defense? The above position arises after 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cd 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 e6 6. Bc4 Nc6 7. Be3 Be7. To get an idea of the fireworks that may ensue, take a look at the amazing game Fischer-Geller from Skopje 1967. This was one of the three losses that Fischer included in his My 60 Memorable Games, so you know it has to be a pretty special game.

The top five:

- B89 (Sicilian Defense, Sozin-Fischer-Velimirovic Attack): 25.2 percent draws

- A44 (Old Benoni, 1. d4 c5 2. d5 e5): 25.5

- B00 (Uncommon 1. e4 openings, e.g. Nimzovich 1. … Nc6, Borg 1. … g5, etc.): 27.5

- C05 (French Tarrasch, including the pawn sac 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nd2 Nf6 4. e5 Nd7 5. Bd3 c5 6. c3 Nc6 7. Ngf3 Qb6 8. O-O!?): 29.5

- A60 (Main Variation Benoni, 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 c5 3. d5 e6, side lines): 29.6

Here we see a couple Benonis, a well-known sharp opening. We already encountered A44 before because it is White’s best/Black’s worst common opening variation, but at least one positive thing about for Black is that it does give him winning chances. I think B00 is on this list because these variations are bad but weird enough to confuse White. B00 is a very appropriate ECO code for them — I think we should call them the “Boo!” Openings. Individually they are all uncommon, but when you scrape them into one catch-all category, they become “common.” Finally, the French Tarrasch is an opening that doesn’t appeal to me a whole lot, but the above pawn sac is a line I really like. If I could always get into this line, I would be happy to play the Tarrasch.

Least Drawish ECO Code — Uncommon Variations

And really, what opening in chess could have more fighting spirit than the venerable Danish Gambit (C21)? Unfortunately it’s not all that good as White openings go, with a winning percentage of only 50.5 percent, but at least White’s heart is in the right place. Basically you play this opening to win or lose, with no in between.

The top five:

- C21 (Danish Gambit): 19.8 percent draws

- C57 (Two Knights side lines, including Fritz, Fried Liver, Traxler/Wilkes-Barre): 23.7

- E80 (King’s Indian Defense, Saemisch side lines): 25.5

- A82 (Dutch Staunton Gambit): 26.2

- C40 (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 side lines, including Elephant Gambit 2. … d5 and Latvian Gambit 2. … f5): 26.4

What a great bunch of gambits! Of course, #2 (the Fritz Variation) used to be a big part of my opening repertoire. Unfortunately, I can’t recommend it any more because the computer has essentially busted it. Maybe the Traxler is still viable for the true romantics out there. I also have played A82 in the past, but the database shows that it’s really bad for White at the master level. At the amateur level, though, you can score a lot of points with it. The Latvian Gambit, #5, gave me (as White) my first North Carolina championship. I was paired in the last round against Tony Magee, an expert who loved the Latvian. Basically his approach to it was to heck with development, let’s just play for a kingside attack. That’s what he did, and it didn’t work, and I became the 1985 North Carolina champion.

I do not know what the Saemisch (#3) is doing on the above list.

Final Comments

Now let me make a huge disclaimer about all of the above lists. In my previous entry I said that this was for fun only, and you should not choose your openings based on these lists. I’m serious about that. If you play an opening that’s congenial to your style, and you truly understand it (both its strengths and drawbacks), you could easily increase your winning percentage by 5 percent or maybe even 10 percent. That’s enough to turn a “bad” opening into a good one, or a very good one.

Also, extreme statistics (the top five, the bottom five, etc.) are notoriously unreliable. Professional statisticians mostly talk about means and deviations from the average, and there is a good reason. It’s known as “regression to the mean.” One thing I can almost guarantee you is that if you asked the same players to play another million games, and you tabulated the best for White, best for Black, etc., you would get different results. The ones that appeared to be the most extreme in this data base would “regress to the mean,” not because of any inherent change but just because their extremeness was a result of chance variation. A lot of games happened to go White’s way, or Black’s way, maybe for reasons that had nothing to do with the opening. The other thing you can say with some confidence is that even though A44, for example, might not be White’s best opening variation if you did the experiment again, it would still be a good variation. That, I think, is the real value of the above lists: not that they identify the best openings, but that they identify some very good openings that you might not have known about.

By the way, I think there is one exception to the “regression to the mean.” I think that if you ran the experiment again, D14 would still be by far the most drawish opening. Compared to all other chess openings, it is an alien; it comes from a completely different distribution of win/loss/draw percentages. When you have samples from the same population, more sampling will tend to emphasize the similarities, hence regression to the mean occurs. But when you sample from two different populations, more data will tend to emphasize the differences, so you don’t get regression to the mean.

Lastly, let me mention again one difficulty unique to this data set. Although the ECO codes have brought a certain amount of order to the jumble of chess opening terminology, there is still a lot of ambiguity about them. One position could be classified under three or four different codes. See, for example, the confusion I mentioned last time about the Four Pawns Variation in the King’s Indian, which can also arise from the Benoni. Or consider the Velimirovic variation, shown above, which is supposed to arise after 7. … Be7. If Black plays 7. … a6, it’s a different ECO code (B88). But who is to say if it’s really different, if black plays … Be7 later? I think the computer can do a reasonably good job of arbitrating, but it’s not perfect, especially if the transpositions can take place over the course of several moves.

Transpositions are also important because they can enable you to bypass dangerous variations while still getting to the position you want. The two people who commented on the Dutch Defense both made this point. The fact that Black allows White to play Botvinnik’s variation with 8. Ba3 (A94) is a sign that Black doesn’t know the Dutch very well. By playing a different move order Black can play … Bd6 and … Qe7, making Ba3 more difficult for White to accomplish.

There, I’ve said all I’m going to say about ECO codes! I hope you enjoyed this series.

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

Darn!! And I had been playing the Veresov too! I had toyed with the idea of the Latvian Gambit, but I seemed to get destroyed whenever I tried playing it. I gave it up. I like the Trompowski (and 1.d4 d5 2.Bg5 also), Torre Attack and London System too. I had no idea the Veresov was so bad!!

I think you should continue to experiment. But one of the things that impressed me about the data base is how much the performance of the openings conforms to conventional wisdom. Offbeat openings really do score worse. As a person who doesn’t care very much for conventional wisdom, I have a little bit of trouble accepting that fact, but I suppose I must.

I suspect the high draw rate in the Flohr-Zaitsev Variation has a lot to do with people choosing the line 9… Bb7 10. d4 Re8 11. Ng5 Rf8 12. Nf3 Re8 etc. for their prearranged draws.

Good catch! I agree!

I have been playing the Exchange Slav as White for quite some time, with a great score–8/10 against experts, masters and IMs. Against the two IMs I played, I got near-winning positions but was later outplayed to a draw. One draw was against an expert who just defended well, and in the last I offered a draw because I got a call that my wife had been unexpectedly sent to the hospital to give birth a month early.

I find that Black players are often unprepared against the ES and don’t take it seriously, but really, one or two imprecise moves and Black is in trouble.

Another Exchange Slav Hero is ICC 5-min legend Olegas, who has thousands of games with the opening and an absolutely disgusting score.