At Mike Splane’s last chess party, about two weeks ago, I was excited to see two people who have been almost absent from the Santa Cruz chess scene for six years: Eric Fingal and Juan Diego (Juande) Perea. In Eric’s case the reason for his absence was personal events that I probably shouldn’t write about. In Juande’s case, the reason was personal events I’m happy to write about — he became a dad! Both of them are testing the chess waters again.

Eric was the organizer of the late lamented Santa Cruz Cup tournaments, which were among my favorite tournaments of all time. There were five of them. The first had six players and was a double round-robin. After that we went up to eight players, which made a double round-robin impractical, so we experimented with different formats.

Still, in all cases the attraction of the tournament was that you had to play several games against players at almost the same level. Everybody knew everybody else’s playing styles and favorite openings, so it was a lot like playing in a GM tournament. You had to watch out for “theoretical novelties” from your opponents.

Another reason I enjoyed these tournaments was that I was pretty successful in them. Here were the results:

| Year | Winner | My Score | My Rank |

| 2003 | Ilan Benjamin | 7-3 | 3 |

| 2004 | Dana Mackenzie | 6½-1½ | 1 |

| 2005 | Dana Mackenzie | 7-2 | 1 |

| 2007 | Dana Mackenzie/ Juande Perea | 7½-2½ | 1-2 (playoff abandoned) |

| 2008 | Juande Perea | 5½-4½ | 4 |

Even in the years when I didn’t do so well, I appreciated the challenging competition. In the years when I won, it was absolutely by the slimmest of margins.

Since the first three Santa Cruz Cups took place before I started this blog, I’ve never written about them before, and I thought it might be interesting to show you some of my favorite games from them.

This game from the 2004 Santa Cruz Cup shows the dangers of prepared variations. Jeff Mallett, my opponent, basically refutes one of my favorite opening lines. On move 15, I played a blunder that wasn’t in his preparation. But because he was following computer analysis, he couldn’t figure out what was wrong with it! He played a move that wasn’t the best, and within a couple moves I had sacrificed a pawn for a huge attack. The finish is really cute: It looks as if he tricked me, but then it turns out that I tricked him instead.

Dana Mackenzie – Jeff Mallett

Santa Cruz Cup 2004

Caro-Kann, “Fugly Variation”

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. e5 Bf5 4. g4!? …

There’s an interesting history behind this move. I’ve played it for years and have a huge plus score with it. A few years ago I wrote a series of blog posts about the variation, which I called the “Homo Erectus Variation” because it is even more primitive than the “Caveman Variation” 4. h4. IM Mark Ginsburg noticed my posts and wrote a great post of his own claiming to refute 4. g4!? He was the person who called this variation “Fugly,” which I assume is a contraction of “f****** ugly.” I like this name better than “Home Erectus Variation,” so it is now officially renamed the “Fugly Variation.”

4. … Be4! 5. f3 Bg6 6. h4 h5 7. Ne2 hg 8. Nf4 Bh7!

The move recommended by Ginsburg. Did Mallett read Ginsburg’s post? No, this game was played four years earlier! Jeff is just following his computer analysis.

9. fg e6!

Again as recommended by Ginsburg. This seems to be the crucial position of the variation.

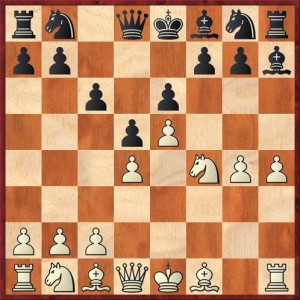

Position after 9. … e6. White to move.

Position after 9. … e6. White to move.

FEN: rn1qkbnr/pp3ppb/2p1p3/3pP3/3P1NPP/8/PPP5/RNBQKB1R w KQkq – 0 10

I had played this position once before (Mackenzie-Gaede, 2003) and repeated the move I had played in that game, which seemed like the most natural to me. Jeff, with his home preparation, blows it out of the water.

Years pass, chess engines improve, and now we can give the position to Rybka instead of some lame version of Fritz. And Rybka finds a whole new idea that I think makes the variation playable again. The idea is 10. h5 Nd7 (Ginsburg) or c5 (Mallett) 11. Ng6!!

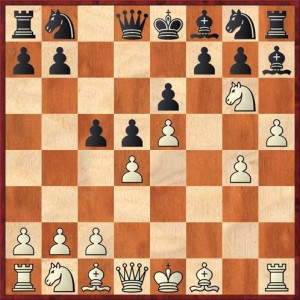

Position after 11. Ng6! Black to move.

Position after 11. Ng6! Black to move.

FEN: rn1qkbnr/pp3ppb/4p1N1/2ppP2P/3P2P1/8/PPP5/RNBQKB1R b KQkq – 0 11

It’s easy to see that 11. … fg is fine for White. But wait, what about 11. … Bxg6? Doesn’t Black just win a knight or a rook?

The answer is no, because of 12. hg! Rxh1 13. gf+! Kxf7 (Black has to take, he can’t allow White to promote) 14. Qf3+ Ke8 15. Qxh1. Now Black can win a pawn with 15. … cd, but it’s a relatively shaky pawn. After 16. Bf4, Rybka evaluates the position as -0.2, i.e., almost full compensation for the pawn for White.

I know that Ginsburg wouldn’t be happy with me for saying “Rybka says so,” so let me discuss this in more detail. I basically agree with what he wrote: “If you are leaving gaping holes in your position, you had better be doing it for immense material gain and/or checkmate.” Except that I think he’s overstating the case. If I can make Black’s king just as vulnerable as mine, then I can play this variation. White’s whole objective is to “tag” Black’s king before he can castle queenside. In the above line, White has succeeded in his strategic goal. Because Black’s king is now just as exposed as White’s is, it’s anybody’s game.

Playing at the sub-GM level, I think it would be a miracle if Black got this far without freaking out, and even if he does get this far, I’m still willing to play the White position.

Now Black can and probably should avoid this Ng6 nonsense by playing 10. … Be4 first. Okay, but then White has a target (the bishop on e4). The whole point of Ginsburg’s post was supposed to be that Black can get a simple advantage by not creating any targets.

Okay! Now, back to Mackenzie-Mallett!

10. Nc3? …

Looks sensible, but now Ginsburg’s admonitions about too many weaknesses in White’s position start coming true.

10. … c5! 11. dc Nc6 12. Bb5 Bxc5 13. Nh5 Kf8 14. Bxc6 bc 15. Bg5? …

Position after 15. Bg5. Black to move.

Position after 15. Bg5. Black to move.

FEN: r2q1knr/p4ppb/2p1p3/2bpP1BN/6PP/2N5/PPP5/R2QK2R b KQ – 0 15

The critical position of the game. My move is so bad that it didn’t show up in Jeff’s pregame preparation; he had only looked at lines like 15. Qf3 Qc7 16. Bf4. Keep this in mind, because it’ll be important.

So, can you find Black’s winning move? Hint: White has two weaknesses, the pawn on e5 and the pawn on b2. Find a move that attacks them both.

15. … Qb6?

Wrong! The correct move was 15. … Qb8!, after which White’s game collapses. If 16. Qe2 Qxb2 is devastating. On any other move, such as 16. Qf3, Black will take the e5 pawn with check, and that extra tempo makes all the difference.

16. Qf3! …

I am still sacrificing a pawn, but now I’m getting all kinds of counterplay for it.

16. … Bd4?!

Technically this is a mistake too. 16. … Qxb2?! is also dubious after 17. Rb1. The correct move, according to the computer, is 17. … Rb8! so as to meet 18. Rf1 with 18. … Rb7 and also to prevent White from castling to safety. But let’s face it, humans (especially class-A player or experts) are not going to find such moves. The real place where Black went wrong was on move 15.

17. Rf1 Qc7

Here is where Jeff realized things were coming unglued. In his home preparation, Black could always play … Bg6. But now, Jeff realized that 17. … Bg6? would be met by 18. Nf4!

18. O-O-O Bxe5

Position after 18. … Bxe5. White to move.

Position after 18. … Bxe5. White to move.

FEN: r4knr/p1q2ppb/2p1p3/3pb1BN/6PP/2N2Q2/PPP1K3/2KR1R2 w – – 0 19

White’s position has gone from lost to winning in three moves! I like the efficiency of White’s development. Every White piece except the knight on h5 has moved just once. Meanwhile, Black has moved his queen twice, his king bishop three times, and his queen bishop four times. No wonder White is better (even a pawn down).

19. Rde1 f6 20. Bf4 Bxf4+ 21. Nxf4 Kf7 22. Nxe6 Qd6 23. Ng5+ Kf8 24. Ne6+ …

Repeating the position to gain time on the clock.

24. … Kf7 25. Ng5+ Kf8 26. Re6! Qh2

Position after 26. … Qh2. White to move.

Position after 26. … Qh2. White to move.

FEN: r4knr/p5pb/2p1Rp2/3p2N1/6PP/2N2Q2/PPP4q/2K2R2 w – – 0 27

Oh, no! Did White miss something? It looks as if Black is winning a pawn, due to the simultaneous threat of mate on c2 and the pawn on h4.

Do you see what White’s resource is?

27. Ne2! …

This just looks like a retreat. But one of Mike Splane’s principles is that when you play a forced defensive move, your opponent will often forget to check whether that move might contain a threat. That is true in spades here.

27. … Qxh4?

Black was lost anyway, but now it’s mate in three.

28. Qa3! Ne7 29. Qxe7+ resigns.

I love this game! Once you get past all the opening stuff, which I admit is important, it’s just about playing better chess than your opponent. Black missed a tricky queen maneuver (… Qd8-b8-e5). I saw a tricky queen maneuver (Qf3-a3-e7). That was one difference. The other thing was that from move 4 on, and even when things started going a bit haywire, I never stopped playing aggressive moves that put pressure on my opponent. If you’re going to go down, at least go down fighting. If you play with that kind of gusto and spirit, a lot of times you will win games that you had no business winning.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

You claimed that 11.Ng6 works after both 10.h5 c5 and 10.h5 Nd7, but in the latter case Black has 11…Bxg6 12.hxg6 Bb4+! 13.c3 Rxh1 and now after gxf7+ Black has …Kf8. White doesn’t have time to capture both the bishop on b4 and the knight on g8 because of threats like …Qh4+. (I must admit that Houdini found this.)

Good catch, Dan! I’m glad you pointed this out before I got caught playing 10. … Nd7 11. Ng6? in a tournament. So really after 10. … Nd7 it looks as if I should play 11. c3, which fortifies d4 and also reinstates the threat of Ng6.