A “tabiyah” is an opening position that arises when both sides play their “most natural” moves, or a position that can arise from a multitude of different move orders. In many cases it is arrived by mutual consent, although this doesn’t have to be the case. And it’s usually a position where one side or the other has to make his/her first substantive decision. So it’s like the point where the game really begins.

In my last tournament, the Bay Area International in January, I got to the same position in two games (both of which I lost) without really realizing it was a tabiyah. It’s a position from what one might call the Quiet Variation of the Two Knights’ Defense, the 4. d3 variation.

John Bryant/Steve Breckinridge vs. Dana Mackenzie

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Nf6 4. d3 Be7 5. Bb3 …

Although I’ve played this variation (4. … Be7) on many occasions, I had never seen this particular move order before. White spends a tempo to reposition his bishop to b3 (and eventually c2) more quickly. The upside of this is that he keeps the two bishops. The downside is that, well, he spends a tempo. Can Black take advantage of this? Does the move order even matter?

5. … O-O 6. O-O d6

A more direct attempt at refutation is 6. … d5. Of course, White hasn’t really made any mistakes so it is hazardous for Black to think about “refuting” White’s fifth move.

7. c3 …

And here we are at the tabiyah.

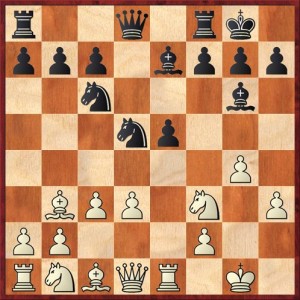

Position after 7. c3. Black to move.

Position after 7. c3. Black to move.

FEN: r1bq1rk1/ppp1bppp/2np1n2/4p3/4P3/1BPP1N2/PP3PPP/RNBQ1RK1 b – – 0 7

Now it’s time for Black to make a plan. A lot of his decision revolves around where to develop his remaining piece, the queen bishop.

By the way, it’s probably no accident that Breckinridge played this against me. He probably saw how I botched it against Bryant in round one and decided to see if I would botch it the same way against him.

Let’s do what I couldn’t do during the games and take a look at the moves most frequently played in ChessBase.

(A) 7. … Na5. Played 668 times, score (for Black) 44.5 percent. This is the simplest and most solid. Black chases the bishop to c2, follows up with 8. … c5 and gets a Ruy Lopez-like position. Why didn’t I play this either time? Well, I just wasn’t sure whether you’re “supposed” to play a Ruy Lopez without … a6 and … b5! This may have been an acceptable excuse against Bryant, but certainly after that game I should have done my homework, looked up the line in ChessBase and realized that 7. … Na5 is the usual move. But I didn’t do that, because I didn’t expect to play this position again for another 20 years. Instead, I saw it two days later! There’s a pretty good moral here. In big-time chess (and the Bay Area International is somewhat big-time) people prepare for you and pounce on your weaknesses.

(B) 7. … h6. Played 401 times, score 40.0 percent. This move is somewhat abstract, but its flexibility is also its main point. Black might play … Be6 or might play … Bg4, and in either case the move … h6 is useful. In the former case it keeps White’s knight out of g5, and in the latter case it gives the bishop a possible flight square on h7.

(C) 7. … Bg4. Played 381 times, score 28.6 percent. This is the move I played against Bryant. I was surprised to see how poorly this natural-looking move scores in practice, but in retrospect I think I understand it. This move is useful in Ruy Lopez variations where White plays d2-d4 and omits h2-h3. However, if White has played d2-d3, the move makes no threats. Black risks getting his bishop kicked with h3; he doesn’t really want to take on f3, and if the bishop drops back to h5 it might eventually get chased with g2-g4. Black has essentially jump-started White’s kingside attack for him. No wonder Breckinridge wanted to see if I would enter this variation again!

(D) 7. … Be6. Played 159 times, score 35.5 percent. This is probably what I am going to play next time. It’s consistent with my opening philosophy of playing moves that are not the most popular but are perfectly good. And there’s more to it than that. Black is more or less inviting White to play 8. Bxe6 fe 9. Qb3, and on this move I’m planning to sacrifice a pawn with 9. … Qd7!?

Position after 9. … Qd7. White to move.

Position after 9. … Qd7. White to move.

FEN: r4rk1/pppqb1pp/2nppn2/4p3/4P3/1QPP1N2/PP3PPP/RNB2RK1 w – – 0 10

We are now into the ultra-rare realm. Black usually plays the ugly, passive 9. … Qc8, and the natural pawn sac 9. … Qd7 has been played in only one game (White didn’t accept). Analyzing the position with Rybka, I believe that Black has very good compensation for the pawn. Rybka evaluates the position at about +0.3 for White, meaning that it doesn’t quite believe Black has full compensation, but I think it’s good enough for rock and roll. White gets to feel very uncomfortable on the kingside. Meanwhile, if White doesn’t take the pawn on move 10, Black has solved all of his opening problems. 10. Ng4 is met by 10. … Nd8. Otherwise, Black is just ahead in development and White’s queen is somewhat misplaced on b3.

I like this line! A more or less sound pawn sac that is unknown to theory!

(E) 7. … d5. Played 111 times, score 55.0 percent! The good record of this move, a positive score for Black, is a strong argument in its favor. It seems surprising at first sight, playing … d5 immediately after playing … d6, but the point is that White’s move 7. c3 has weakened the d3 square and also deprived the queen knight of c3, thereby weakening White’s control over the d5 square.

To me, the most thematic continuation goes as follows: 8. ed Nxd5 9. Re1 Bg4 10. h3 Bh5 11. g4 Bg6 (diagram).

Position after 11. … Bg6. White to move.

Position after 11. … Bg6. White to move.

FEN: r2q1rk1/ppp1bppp/2n3b1/3np3/6P1/1BPP1N1P/PP3P2/RNBQR1K1 w – – 0 12

The lines are clearly drawn here. Black believes that his superior mobility, the weakness of the d3 square, and the weakness of White’s kingside give him sufficient compensation for the pawn after 12. Nxe5 Nxe5 13. Rxe5. This position has been played by some heavy hitters for Black: grandmasters Fressinet, Ragger, and Handoko.

One thing makes me uneasy, though. In the lines I’ve gone over with Rybka, Black’s compensation tends to disappear. Rybka does not like this pawn sac as much as the pawn sacrifice in variation (D). I know that Rybka is not the same as a human opponent, but still it makes you wonder.

I think I will try variation (E) sometime too, if I’m given the opportunity, but I want to try (D) first.

FInally, let’s skip down to the 14-th most popular move in the tabiyah:

(N) 7. … b6. Played 3 times, score 16.7 percent. This is what I played against Breckinridge, because I was at my wit’s end. I still didn’t know whether 7. … Na5 was considered good, and I didn’t want to repeat my 7. … Bg4 debacle against Bryant, so I had to find some other move. This was the one I picked. Ironically, Rybka does not consider it a bad move at all. It’s perfectly playable. But the real problem was that I had nothing even resembling a plan. White got his usual “Spanish torture” attack on the kingside and I had no pressure anywhere. I tried busting the position open with … d5, which was extremely ill-advised because open lines go to the player who is better developed, and that was White. Bottom line, even though Rybka says it’s okay, I’m never going to play 7. … b6 again. You’re welcome to try it if you want.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

You’re right about the dubiousness of …Bg4 in these positions. A couple of other drawbacks you didn’t mention:

1) With a White pawn on c3, the pin on the knight is a lot less interesting, since …Nd4 is never an option.

2) When the bishop gets kicked back to h5, you mention that it could get driven back again with g4, but often even more effective is to hit it with Nbd2-f1-g3 and get a free tempo on the way to f5. Sometimes White can even do this before castling.

The fact that …Bg4 is so tempting in these positions is a nice feature of this system (for White). It’s hard to resist if you haven’t already learned the pitfalls.