Something about chess club is good for prying words loose from the depths of my memory. A few months ago I wrote about how a night of chess helped me remember the word “oxymoron.” Tonight’s word is somewhat simpler, but it’s a beautiful one: “poise.”

Here’s what brought that word to mind. Before chess club I was feeling really confident, for some reason. I think it was because I had been looking back over my chess notebooks from 1988, and it kind of brought back the frame of mind I was in back then. I had just won my second North Carolina championship, reached a National Master rating (and gotten the certificate that goes with it), and won an open tournament for the first time. I think that I have never been quite as confident about my chess as I was in the first half of that year. And of course (as you know from my last entry) I had just fallen in love, which made everything in the world seem happy and wonderful.

So this confident frame of mind carried over into chess club tonight, and I managed to win all three of my games in spite of the fact that they were played at a fast time control of game/15, which I usually detest. After chess club I was trying to think of the word to describe how IÂ played tonight, which is a way that I don’t usually play, and the word came to me.

Poised.

I’m always impressed by people who remain calm throughout the ups and downs of a chess game, and especially during time trouble. But an even better, more powerful way to be is poised. The state of poise includes being calm, but it also includes something else. It brings to mind a sense of balance and preparedness. It comes from the French word “poids,” meaning weight. So think of weights, perfectly balanced. A tightrope walker crossing a chasm: that’s poise. Poise is not about avoiding trouble, but being ready to cope. That is what you are aiming for as a chess player.

My most interesting game tonight was the third one. Actually, I’m not sure how good this example is, because I made a really stupid move and then got outrageously lucky. But at least I never panicked. It was my opponent who panicked, even though he should have been winning.

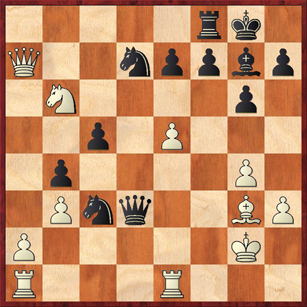

What do you think about this position? What should White do?

I’m playing White against Sam Sternlight, who usually doesn’t get to play in the top quad, so he was a little bit intimidated. He has sacrificed an exchange for a pawn, but he’s actually in quite good shape here. He’s got pressure on my pawn on e5, and lots of nice squares for his knight on c7, which is threatening to go to d5 or b5 and from there to c3 or d4. Also, White’s position is kind of loose, with lots of undefended or weak pawns or pieces. Finally, White has to come up with a defense to the specific threat of … Nc7-b5-c3, winning an exchange.

Thus I think the best move is 1. Rb2, which prevents the fork and prepares to swing the rook over to f2 after 1. … Nb5. The rook also defends the pawn on a2 and may be able to create threats against f7 at some point.

Instead, I succumbed to the temptation of winning a pawn and played 1. Qb7?? A really misguided move, abandoning the center and leaving even more squares unprotected in my position, such as d4 and d3. My only excuse is that I had about 3½ minutes left and my opponent had 6, so basically we’re playing speed chess here. 1. Qb7 is a real speed-chess kind of move; hopefully I would have better sense in a tournament.

Sam continued naturally with 1. … Nd5 2. Qxa7 Nc3 3. Ra1 (again, 3. Rb2 might have been better) Qd5 4. Nb6 Qxd3 5. Kg2?!, reaching the position shown below.

Black has lots and lots of ways to win. The one that looks most convincing to me is 5. … Ne4, which threatens 6. … Qxg3+ followed by mate, so White cannot afford to take on d7. The knight also blocks the rook’s defense of e5, so Black is threatening also 6. … Nxe5 with really big threats. The computer gives Black a 7-pawn advantage here!

But Sam played 5. … Qd2+?, which I think you can find in Wikipedia under the entry “pointless check.” Again, it’s very much a speed-chess move; in speed chess you tend to play checks first and ask questions later. The game continued 6. Bf2 Nxb6? (6. … Nxe5 still wins) 7. Qxb6 Qd5+ 8. Kb1 Bxe5 9. Qxc5.

Sam explained after the game (well, actually even during the game he said this)Â that he just missed this move. The momentum has shifted once again — I’ve navigated the tightrope and gotten safely to the other side of the chasm. However, Black still has a very playable position, if he does the right thing here. What would you do?

Sam did exactly what I expected — he played to win back the exchange with 9. … Qxc5? 10. Bxc5 Ne2+ 11. Rxe2 Bxa1. But luck was with me again — it turns out that winning the exchange wasn’t the best idea for him, because I played 12. Bxb4 and my queenside pawns started running. Instead, after 9. … Bd6! 10. Qxd5 Nxd5, Black would have had excellent drawing chances. White’s extra pawn on the queenside is very hard to activate, maybe even impossible.

I don’t know if this game had to do with poise or just plain luck, but anyway, that’s the kind of night it was.

{ 11 comments… read them below or add one }

Last night when you were showing me that variation with the grand prix.

Can you tell me were to find that variation? thanks

-thadeus

Hi Thadeus,

The variation I showed you goes 1. e4 c5 2. f4 d5 3. Nf3!? ef 4. Ng5 Nf6 5. Bc4. Black should probably play 5. … e6 here, but if he is bold enough to play 5. … Bg4 then White can sac his queen with 6. Qxg4! I wrote an article about this in Chess LIfe, March 2007, pp. 30-33 (“Sac Your Queen on Move Six! (a New Anti-Computer Variation”). Since the article came out, some people have pointed out that it should be called the Bryntse Variation, after a Swedish correspondence player, but there is virtually no theory on it.

Note that 4. Ne5 is also possible, and might even be better.

In both cases (4. Ne5 and 4. Ng5) White is playing a Budapest Gambit a tempo up, having spent the tempo on f2-f4. This makes a pretty big difference, both pro (White has more influence in the center) and con (White has weakened his kingside). Either way, if you play this variation you are blazing new territory — there are no books.

Thanks i will look into it.

If 8…Ke8 is it just a draw.

Maybe, maybe not. White can, of course, choose to take a draw by repetition with 9. Bf7+. This may be the prudent course against a higher-rated opponent (but, for that same reason, a higher-rated opponent is unlikely to play 8. … Ke8). However, White doesn’t HAVE to go for the perpetual. He can also play 9. Bxg4, and he gets much the same kind of counterplay that he does with the Black king on c6 or c7. Remember that Black cannot castle any more, so he is quite exposed on e8.

With best play I think that Black may have a slight advantage after 8. … Ke8 9. Bxg4, but I don’t think that should dissuade White from playing this. Black will still have to work very hard to defend successfully.

Bottom line: If you’re playing against a higher-rated player or in a situation where you don’t mind a draw, you can play the queen sac variation 6. Qxg4 with no hesitation. if you’re playing a lower-rated player or need a win, you can still answer 8. … Ke8 with 9. Bxg4 and enter completely uncharted territory. But if that makes you too nervous, you can try 4. Ne5 instead. which is also quite unexplored (and you at most have to sac a pawn, instead of a queen!).

Thanks sorry about all the questions but I have one more. After 1. e4 c5 2. f4 d5 3. Nf3!? ef 4. Ng5 Nf6 5. Bc4 Bg4 6. Qxg4 Nxg4 7. Bxf7+ Kd7 8. Be6+ Kc6 9. Bxg4 e5!! doesnt black seem to have a dominating position because if white moves the knight Qh4+ and now the blacks bishop is freed up?

Hi Thadeus,

You just fell into the main trap! After 9. … e5? 10. Nf7! Qh4+ 11. g3 Qxg4?? 12. Nxe5+ forks Black’s king and queen. I think that this trap alone will win you some speed games or Internet games. In fact, the first time I played this opening in a tournament game, this is exactly what my opponent did. On move 11 he picked up my bishop to take it, and then all of a sudden he saw the fork, and he just froze. He sat there for about two minutes, even though the touch-move rule said that he *had* to take the bishop. (Conveniently, a friend of mine was watching the game and ready to vouch for me in case my opponent tried to claim he hadn’t touched it.) Finally he took the bishop, I played the check, and he resigned.

That was sweet, but then the next day I got to play the game against David Pruess that I wrote about for Chess Life, and that was even sweeter.

By the way, I should also mention that if Black doesn’t fall into the fork, and plays (say) 11. … Qf6, White should take the pawn with 12. Nxe5+ rather than the exchange with 12. Nxh8. After 12. Nxe5+ White is ready to play 13. Nc3, threatening 14. Nxe4 or 14. Nd5+ with even more tempi gained against Black’s queen. It’s very easy for Black to spend all his time getting his queen chased around and never get the rest of his pieces out!

If Black develops his KB to d6 at some point, White doesn’t particularly mind because a bishop for knight exchange gives him two unopposed bishops. (This is in fact what happened in the Pruess game.) The configuration of 2 B’s versus Q is so rare that most people don’t realize this, but 2B + 2P is almost complete material compensation for a queen. White is *not* a pawn down at that point; it’s more like a third of a pawn.

wow thanks that helped a lot .I have already won three games with this queen sac. 🙂

thanks, it helped me a lot to win games from those from whom i never expected.

Dana,

Thanks for posting the game. It’s nice it from your perspective.

Thanks,

Sam

{ 1 trackback }