In the comments to my latest post there was some interesting discussion of the “lost art of the post-mortem.” However, I was fortunate enough this weekend to have a delayed postmortem of two of my games from the CalChess State Championship.

In this case the postmortems were not with my opponents, but with my friends Gjon Feinstein, Mike Splane, and Cailen Melville. In both cases I gained a great deal of insight. Even though the comments of Gjon and Mike were not always 100 percent accurate, it was nevertheless very helpful to see how other people thought about the positions.

In my first-round game with Gabriel Bick, where I had Black, let’s look at a couple points that I did not perceive as turning points during the game, but which in fact were. (See Not About the World Cup! to see my original thoughts on this game.)

First, here’s a position where not much seems to be happening.

FEN: r3r3/pp4k1/3q1p1p/2p2bp1/2Pp3P/1P1N4/P1PQRPP1/R5K1 b – – 0 22

Here Bick has just played 22. Re2, and I more or less reflexively traded rooks, 22. … Rxe2 23.Qxe2 Bg6, because I wanted the e-file for myself. What I missed was 24. Qf3!, probing the undefended pawn on b7. Of course I can defend it with 24. … Rb8, but then White takes control over the e-file, which is just what I had wanted to prevent.

Instead I chose to sacrifice the b-pawn, which led to some exciting tactics later on. But one point that emerged from our discussion was that I need to solidify all the weaknesses in my position before entering complications. Here was a good chance to play 22. … b6, which not only strengthens my b-pawn but also the c-pawn. Gjon, Mike, and Rybka all agreed on this point. If I play this move, I never even have to sacrifice a pawn. And I have a small but persistent advantage because of my better minor piece and the possibility of expanding on the kingside. White’s control over the e-file is not a very big issue.

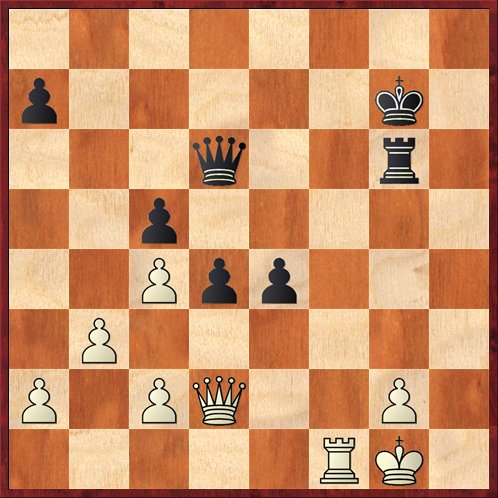

Another important position came up after the tactics had begun.

FEN: 8/p5k1/3q2r1/2p5/2Ppp3/1P6/P1PQ2P1/5RK1 b – – 0 34

Gjon and Mike both thought that Black should be winning here, and that my mistake was playing 34. … e3 in this position. The first part of their conclusion seems flawed, but the more important point, that I should not play 34. … e3, is nevertheless correct.

First, let me point out that in my earlier blog post I did not mention any alternatives to 34. … e3. During the game I did look at other things, principally 34. … Qg3. However, there was an intriguing flaw in my thought process. I was still thinking in middlegame terms, and hoping to mate my opponent on h2. For that reason I thought it was critical, in fact almost a no-brainer, to play … e3 in order to take control over the f2 square.

However, I had to realize that there is not sufficient time for me to mate my opponent on h2. Whether after 34. … Qg3 35. Qf2 or after 34. … e3 35. Qe2 Qg3 36. Qf3, I’m going to have to consent to the trade of queens. So my first sin was thinking in middlegame terms about a position that is soon going to be an endgame.

Second, I should have asked, which endgame do I want to play — the one with the pawn on e3 or the one with the pawn still back on e4? Here, again, it’s a no-brainer. After … e3 my pawns are static and not going anywhere. With the pawn on e4, either pawn can push, and moreover there is another possibility. After 34. … Qg3! 35. Qf2 Qxf2 36. Rxf2 I have the possibility of 36. … Rg3!, crossing with my rook over to c3. This is an extremely dangerous plan. For instance, after 37. Rf5? Rc3 38. Rxc5 Rxc2 39. Rc7+ Kf6 40. Rxa7 White is lost, in spite of being two pawns up. After 40. … d3 White cannot stop my connected passed pawns.

What Gjon and Mike failed to appreciate was that two can play this game. While I avoid playing … e3, my opponent should try to provoke it. So in fact his best defense after 36. … Rg3 is 37. Rf4! If 37. … e3 we transpose into the game, more or less. If 37. … Re3 the rook is uncomfortably situated in front of the pawns. Finally, if 37. … Rc3 38. Rxe4 Rxc2 39. Rd7+ we again get a position where White is two pawns up, but this time he doesn’t have to contend with connected passed pawns on the sixth rank. Rybka prefers 37. … Re3 and confirms my assessment that the position is about equal.

So, you might ask, what’s the difference? I played 34. … e3 and drew. I could have played 34. … Qg3, and again with best play it’s a draw. So should I conclude that Gjon and Mike were giving me bad advice, or at least irrelevant advice?

No, in fact, their advice was good, and it highlights why getting the “objective evaluation” from Rybka (or the computer program of your choice) does not always give you the whole picture. The two lines are not equally drawn. The line that Gjon and Mike recommended is better because it is more flexible. It keeps the pawn structure fluid and gives me a broader choice of possible plans — some of which can very easily lead to a winning position if my opponent plays carelessly.

So in the end, even though the analysis session did not turn up any missed wins for me, it turned up ways in which I could have played better and given my opponent more ways to go wrong. And that’s really what analysis is about. Not “Was I winning?” in some ideal, Platonic world, but “How can I play better in the future?” Answer: More prophylaxis. More flexibility. More patience.

The second game, against Myagmarsuren, illustrated some of the same themes.

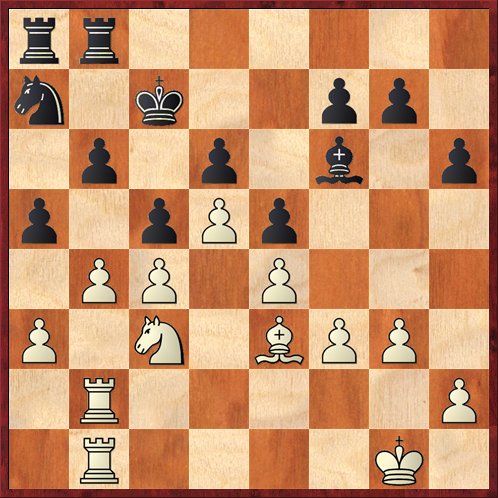

FEN: rr6/n1k2pp1/1p1p1b1p/p1pPp3/1PP1P3/P1N1BPP1/1R5P/1R4K1 w – – 0 36

It’s interesting that I have to cite this as an example of a game where I was not patient enough, because I thought that I was much more patient in this game than I normally am. Still, it was not enough.

In this position my thought process was more or less as follows. I have gotten all my pieces into their optimal positions. I can saddle my opponent with a weak and isolated a-pawn, which will be difficult for him t0 defend. Therefore, I played 36. ba ba 37. Bd2 Rxb2 38. Rxb2 Nc8 39. Na4 Bd8 40. Rb5 Kd7 41. Kf2 Ra6 and then, as discussed in my previous post, I went berserk and sacrificed the exchange with 42. Rxc5!?!

Now, a first interesting point that came out of our analysis is that the exchange sac seems to be completely sound and in fact winning for White. So again, by the Platonic standard we might conclude that I did not make any mistakes and, in fact, won a brilliant game.

But if we take the viewpoint that the purpose of analysis is to determine how I could have played better, rather than to determine the “objective truth” about a position, then we have to conclude that my play came up short. Let’s go back to the position in the diagram, where I opened the game with a pawn trade. Do I really need to do this yet?

My thinking was that I’ve got all my pieces in their best positions, so now is the time to open the position. Quick quiz: What’s wrong with this thinking? What piece did I forget about?

You got it! The King. He is far from the best place. One obvious way to improve my position is to maneuver him to d3. Note that I can do this essentially without penalty, because my opponent is not in a position to undertake any aggressive maneuvers. If my king had already been on d3, the exchange sac I played in the game would have gone from “winning only by a miracle, and only after deep analysis” to “obviously winning.”

Not only that, Mike pointed out, I can even move my king up on the kingside! In fact, a quite serious plan is to move my king to f5 and then take on h6. Of course Black can stop this plan, but in order to stop it he has to make pawn moves. And pawn moves create weaknesses. If I can create a weakness on the kingside, perhaps pry open another file over there, I can play the two sides off against each other and probably win easily. No heroic sacrifices required. It’s the Russian “two weaknesses” theory.

Okay. Well, there’s an obvious difference between Mike and me in our approaches to chess, but in this case I think he clearly had the right way of thinking about the position. My way of thinking, with a tactical shot that in fact was not as well calculated as it should have been, carried with it a huge chance of losing a position that should have been an easy win. His way had no risk of losing, and every chance of inducing my opponent to blunder because of his own impatience.

Lessons: Ask yourself where your pieces belong. Don’t forget that the king is a piece! And while there is still a possibility of improving your position with flexible moves, you should do that instead of making committal moves that irrevocably change the position.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Very insightful analysis of the last position!

For the first position, remember: LPDO.

Great post, very insightful.

I always find it difficult to play these patient moves. As I’m afraid my advantage will slip away.

{ 1 trackback }