Going into the last round of the 1985 North Carolina Championship, I had a score of 4-1 and a date on second board with Tony Magee, another expert who was having a great tournament. As I’ve mentioned previously, the leaders with scores of 4½-½ were masters Randy Kolvick and Rusty Potter; however, Potter was not eligible for the title of North Carolina champion because he wasn’t a state resident. I was not aware of this fact until after round 6 concluded, though.

Magee was a perfect opponent for the last round, a very tactical player who loved the Latvian Gambit. Tigran Petrosian (the former world champion, not the GM who just tied for first in the National Open in Las Vegas) once said, “If your opponent wants to play the Dutch Defense, you shouldn’t prevent him!” The same thing is true of the Latvian Gambit. I knew it could be dangerous, but I was glad to have the chance to get a sharp, double-edged position, in which my opponent would be the one taking the risks.

Maybe I’ll do a ChessLecture some day about this game. The title of the lecture would be very simple:

Develop Your Pieces!

We all know that one of the most important things to do in the opening is to get all of our pieces out. Yet in the midst of the fray, there are often other things that seem to be higher priorities. Over and over, Tony had chances to finish developing his queenside, but there always seemed to be something more important to do. In the end, his lack of development killed him.

Dana Mackenzie–Tony Magee

North Carolina Championship 1985 (round 6)

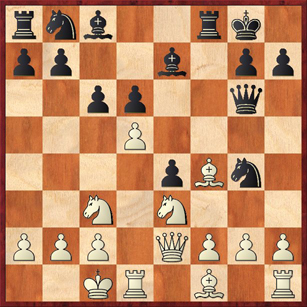

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 f5 (the Latvian Gambit) 3. Nxe5 Qf6 4. d4 d6 5. Nc4 fe 6. Nc3 Qg6 7. Qe2 … (This is a book move, but I think it might be the wrong square for the queen. Perhaps the right plan is Bf4 followed by Ne3 and Qd2. You’ll see why in a moment.) 7. … Nf6 8. Bf4 Ne7 9. Ne3 c6 10. d5! … (I thought this move was quite important, artificially isolating Black’s e-pawn and also taking squares away from his queen bishop.) 10. … O-O 11. O-O-O Ng4?!

White to move.

The first surprise of the game, and at first sight quite an unpleasant one. White can’t play 12. Bg3 because after 12. … Nxe3 both captures are bad. 13. Qxe3 loses the queen to 13. … Bg5 and 13. fe loses the exchange after 13. … Bg4. This is why the square e2 may not have been the best place for my queen.

Still, Black’s development is somewhat lagging, and this move doesn’t help. In principle, White should have adequate resources. And as you all know, I love to defend an attack with a counterattack. So here I offered a pawn sacrifice:

12. h3! Rxf4 13. hg Bg5

If Black takes the gambit with 13. … Bxg4 14. Nxg4 Rxg4, either 15. f3 or 15. g3! (the computer’s suggestion, laying siege to the e-pawn) are very promising. Or if 14. … Qxg4, White plays 15. f3 Qg5 16. Kb1 ef and now a great in-between move: 17. Qe6+! (17. gf? is not as convincing after 17. … Qe5.)

All of this is computer analysis 20 years later — I didn’t see any of this stuff at the time. But I did see the e-file coming open and the g- and h-files too, and thought I would get good compensation for my pawn. Magee apparently thought so too, because he didn’t take.

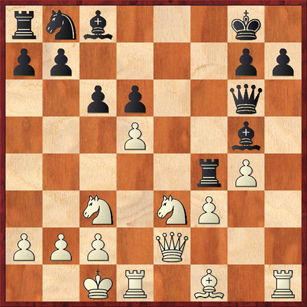

14. f3 ef 15. gf …

Black to move.

Nothing particularly dramatic is happening in this position, but it’s what doesn’t happen over the next two moves that ends up deciding the game. Now was the perfect time for Magee to start bringing his queenside pieces into the game, with … Nd7, … Ne5, and … Bd7. Instead he continues to think that there are more important things to do. First he plays an unnecessary pawn move. Then he starts getting crazy ideas of attacking me on the f-file. Meanwhile, half of his army languishes at home…

15. … c5 16. Kb1 Qf7?

After 16. … Nd7 Black would still be in the game, although the computer likes White after 17. Ne4 Ne5 18. Bg2 Bd7 19. Nf5! building up the pressure on d6. I’m not sure what Magee liked about 16. … Qf7, but perhaps he was anticipating my response and thought he was setting a trap.

17. Ne4 Rxe4?!

In for a penny, in for a pound. On the passive 17. … Be7 White can combine attack on both the kingside and the center: 18. Qh2 g6 19. Nc4 and surprise — Black can’t defend the d6 pawn!

18. fe Qf4

A clever move, and this must be the point of Magee’s combination. He must have seen that 19. Nf5?! g6! would trap White’s knight. Interestingly, though, the computer says that White has a winning advantage even in this line. He simply sacrifices the knight and has overwhelming kingside threats after, for instance, 20 Qd3 threatening Qh3.

But again, there was no need for White to get that fancy. White has a simple defensive move that Magee must have overlooked.

19. Rh3 …

Everything is defended! If Black could bring more pieces to the kingside quickly he might have something, but they are all still sitting in the box.

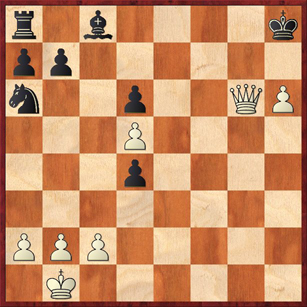

19. … h5 20. Rf3 Qxe4 21. gh Na6 22. Qf2 Bf6

White to move.

For most of the game I’ve just been swatting away my opponent’s threats, but now it’s time for me to have some fun and make some threats of my own.

23. Rxf6! …

This is a whole rook sacrifice, not just an exhange sacrifice.

23. … gf 24. Qxf6 Qxe3 25. Bd3 Qg3

Note that Black has to keep an eye on the g1 square, otherwise White’s rook will go there and mate in two. I think the prettiest finish would have been: 25. … Qd4 26. Bh7+ Kxh7 27. Rxd4 cd 28. Qg6+ Kh8 29. h6! This picturesque finish deserves a diagram:

Position after 29. h6! (analysis)

Do you think Black wishes now that he had developed his queenside?

Instead, Magee played 25. … Qg3, and I finished the game with 26. h6! Also a picturesque finish — there is nothing Black can do to prevent h7 with checkmate. Black resigned.

The Aftermath

After I beat Magee and Potter beat Kolvick, I knew I had finished second in the tournament, and I was very happy with that. It was the best tournament of my life to that point. And then it got even better when Leland Fuerstman, the organizer, informed me that Potter was ineligible and I was the new state champion!

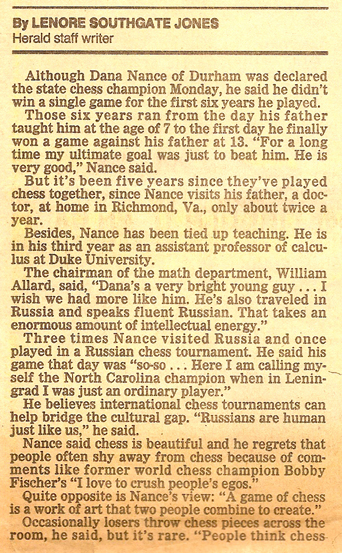

Leland sent out a press release, so a day or two later my local newspaper sent a reporter out to interview me. This was also a first for me — the first time I had ever been written about in a newspaper! Here is the clipping. Let me warn you about two things. My name was different then (I changed it from Dana Nance to Dana Mackenzie when I got married in 1989). Also, watch out for the muttonchop sideburns! (They also came off before I got married). Don’t say I didn’t warn you!

Recognize the position in the photo? It’s from the game with Neal Harris from round five, just before I sacrificed my rook. The photo was taken in the student/faculty lounge in the math department.

It was amusing to read this article, because it got a lot of little details wrong while getting the overall story right. I beat my father for the first time when I was 10 (or maybe even 9); age 13 was when I started playing in tournaments and beating him regularly. I was NOT an “assistant professor of calculus.” This is probably the second most common misconception about mathematicians! (The most common one is that we just sit around adding really big numbers.) The Russian chess tournament took more than one day — it was a game a week for eleven weeks. And I seriously doubt that I told the reporter I was going to use the prize money to shop! In fact, nearly all of it went into savings. I don’t remember whether I threw a party; probably not.

But it’s definitely true that a chess game is a work of art that two people combine to create. I’m glad that the writer liked that quote enough to put it in the headline.

I hope you’ve enjoyed these six “works of art”! Actually, I have seldom played six games as interesting as these in one tournament, with queen sacs and rook sacs and piece sacs and lots of attacking and counterattacking. In the final analysis, maybe playing six exciting games was worth more than winning the title…

NOT! You can have the games; I’ll keep the title.