The only contest in the world that has lasted longer than Barack Obama vs. Hillary Clinton is the Santa Cruz Cup chess tournament. We got started back in October and we’re still going — but we are now, I think, just one round short of completion. On Sunday two games were played, and they both had some amazing twists and turns.

A reminder of where we were before: After an 8-man round robin, we split into two quads, with the top four finishers in the championship bracket and the bottom four in the consolation bracket. Let’s start with Ken Seehart vs. Yves Tan in the consolation bracket.

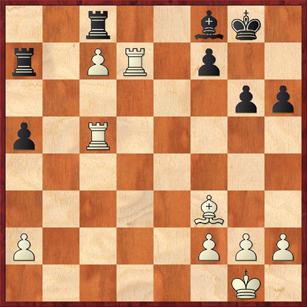

Ken, as White, had the advantage most of the way, but Black can now draw. Do you see how? Hint: Don’t look very hard!

It really shouldn’t be too hard to take a rook that’s en prise, right? After 29. … Bxc5 30. Rd8+ Kg7 31. Rxc8 Kf6! Black has tucked his king in the one place it can’t be checked. White is powerless to prevent Black from attacking the c7 pawn with his bishop and winning it, so the game is drawn.

Nevertheless, Yves saw a ghost — admittedly the threat of Rd8+ was sort of terrifying — and played 29. … Kg7?? instead. Now after 30. Rc6, White won, because Black could do nothing to prevent Bd5 and a gradual demolition of his kingside.

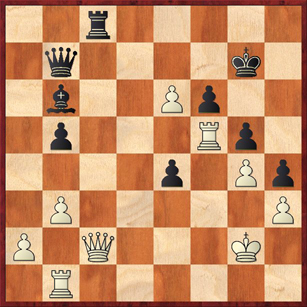

In the championship bracket, some even stranger things were happening. Juande Perea (White) and Ilan Benjamin (Black) reached the following position, with White to play move 35.

Juande, like Ken, was in control for most of the game, but he has allowed Ilan to play a very dangerous exchange sacrifice. Is there any way for Juande to keep an advantage? Is there any way for him to hold the position?

This is a very very difficult position for White, because all of his simplest defenses — based on interposing on f3 — turn out badly. For example, 35. Qe2 (probably what I would have played) e3+ 36. Rf3 Qe4! is ultra-nasty, and 36. Qf3 Rc2+ 37. Kh1 Qc7 with an unstoppable mate threat is pretty appalling, too.

Instead, the computer says that White’s only defense is to head to h1 with his king! So 35. Qb2 (a more forcing move than Qe2, because it threatens f6) e3+ 36. Kh2 Qc7+ (if 36. … Bd4 White defends calmly with 37. Qg2) 37. Kh1 Qc6+ 38. Qg2 Qxe6. Yet even this position is very dangerous for White, and the computer says that White has only one equalizing move, 39. Re1. And even then it gives Black a small edge in the exchange-down endgame.

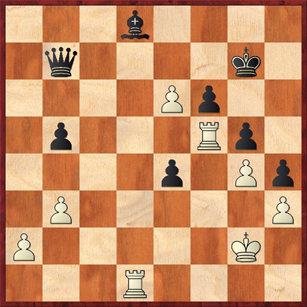

Instead Juande played 35. Qd1?, which he gives two question marks, but I think that under the circumstances one question mark is quite enough. Now Ilan played the nice in-between move 35. … Rd8! after which he is completely winning, because he now threatens 36. … e3+ followed by 37. … Rd2. Juande could find nothing better than giving up his queen with 36. Qxd8 Bxd8 37. Rd1, which brings us to the second unbelievable mistake of the day.

Here Ilan played 37. … Qc7??, overlooking Juande’s simple threat, 38. Rd7+! And so within the space of three moves, the game has gone from drawn to a win for Black to a win for White.

Ilan wrote, “With 25 minutes to play the next three moves, I took 5 seconds to play the astonishing blunder 37. … Qc7. I was fixated on the [White] king and did not notice the fork. Of course, 37. … Qb8 wins.”

I often say that my worst moves are either the ones that I spend the most time on or the least time on. The first kind are bad because I think too much, and convince myself not to play the most natural move. The second kind are bad because I think too little, and don’t see something that’s there. Ilan’s mistake seems to be a good example of the second kind.

This loss was especially tragic for Ilan because he has been the steadiest and most consistent player throughout the tournament, winning the round-robin phase by a large margin with a 6½-½ score. (Juande and I were second at 5-2.) But now he will have to settle for either third or fourth place. In the playoffs, Juande now has 2 points out of 2, Dan Burkhard has 1½, Ilan has ½, and I have 0. Juande will play against Dan for the championship, and I will play against Ilan for third place.