I just finished watching Jesse Kraai’s second lecture on one of my games from Tucson, the game with Jacob Berger that I wrote about here. I found this one slightly less satisfying than the first, but it’s no fault of Jesse’s. The way I played the opening was just outrageously bad, and I can picture poor Jesse picking his way through it and holding it at arm’s length as if it were a smelly fish. Heck, even I feel that way about this opening.

Even so, Jesse has woven an instructive lecture out of a pile of fish guts, and that is no small accomplishment! Here are some of my comments and the things I liked about the lecture.

First, his main point, the dynamic imbalances. No, I don’t think that I ever sat down and looked at the moves 2. f4 and especially the move 4. Ne5? strictly from the point of view of the imbalances I was creating. Basically, I just wanted to dive into the tactics. Of course I recognized that these moves were unorthodox, but for me that was part of the attraction. I like unorthodox stuff. You know that about me.

Jesse went beyond that and said okay, why are these moves unorthodox? Let’s not look at any variations at all! Let’s just understand the positional factors. And once you do that, the moves start smelling so bad that no one would be tempted to play them. Okay, I might keep playing 2. f4 some, but I’m definitely over the move 4. Ne5. As Jesse said, the only thing I accomplished with this move and my next was to trade off Black’s worst piece (the B on c8) for my best, or at any rate my most-moved piece (the N on e5).

I also really liked Jesse’s way of looking at my home analysis of the line that would have ensued after 9. g3 (instead of the blunder 9. Bf3?).

Here in my home analysis (and in my previous blog entry) I came up with “9. g3 c4 (forced) 10. d3 cd (forced)” and analyzed it to a slightly better position for White. But wait a minute! What about that move 10. … cd? It’s not forced at all! It’s only forced if your paramount goal as Black is to maintain material equality. But with all the advantages that Black has, why should he be concerned about material equality? Think about the dynamic imbalances in development, space, open lines, king safety. Black would be foolish to give all of that up just to stay even in material. Let White have the pawn, and play 10. … Nc5 (or even 10. … Qa5+ first)Â 11. dc bc 12. Bxc4. Notice that White had to spend yet another tempo to win the pawn.

This line does, I believe, show a bona fide difference between amateur and master chess. Amateurs (and in doing this analysis, I definitely was thinking like an amateur) tend to make material the most important consideration. This line would probably work against an 1800 player, but it would definitely not work against a grandmaster. That’s one reason you won’t see me play 4. Ne5 again.

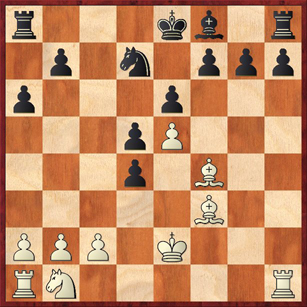

Jesse’s second interesting point came in this position, which I also discussed in my earlier blog post.

Jesse agrees with me that Black should have played 15. … f6, although the move that Black actually played, 15. … Rc8, cannot be too bad. But he says that I missed the best move after 15. … Rc8. I spent 21 minutes (!!) debating between 16. Kd1 and 16. Kd3, when in fact neither is the best move; I should have played 16. c3. Again, a nice dynamic move indicative of the difference between master and amateur chess. During the game I was still hoping to win Black’s pawn on d4 — a futile hope if there ever was one — and therefore I perceived 16. c3 as a “pawn sacrifice.” What a wrong-headed approach! First of all, I had to be objective and realize that White has no chance to win the pawn on d4 outright. No chance at all. So 16. c3 is in no way giving up a pawn. And second, even if it were a pawn sacrifice, what’s the problem in that? My number one challenge is to finish developing. I have an extra piece, and my only chance to save or win this game is to get my pieces developed and in active positions. (In fact, that’s how I did eventually win the game.) So I should have been glad to play 16. c3 dc 17. Nxc3, because it helps me achieve my objectives.

Once again, my move reflected an unhealthy preoccupation with the material imbalance, which distorted my judgement and blinded me to the other dynamic imbalances in the position. It is embarrassing and even a little bit mystifying why I continue to play this way, because it’s contradictory to my own lecture, “Eight-Dimensional Chess (inspired by Jeremy Silman).” It’s obvious that my own lesson hasn’t sunk in yet. I just need to practice what I preached.

Great lesson, Jesse! Thanks so much!!

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Proving that insensitivity to dynamic imbalances did not stop Dana from winning the game.