A lot of you know already that I give regular lectures at www.chesslecture.com, a subscription website with some of the best chess instruction on the Web! But I think this blog is getting more and more readers who aren’t subscribers to ChessLecture, and so for those readers I’d like to offer a little taste of what you’re missing. For those of you who are subscribers and have seen my most recent lecture, called “Berserker Pawns,” I’ll tell you a little bit of behind-the-scenes stuff so that this posting won’t be just a recap of my lecture.

The idea for this lecture came to me several months ago when I was going over some of my old games, mining them for ideas. As Jesse Kraai has often said, the most important part of your chess training is going over your own games. I totally agree with him. Since 1984, I have made a point of analyzing every single tournament game that I play and putting it in a binder. (There was one exception — in the years 1989 and 1990 I got too far behind and just gave up, so I have a folder of unanalyzed games from those two years. That was right after I got married, so maybe you can figure out why I didn’t have time for analyzing all my games!)

Mostly I have not looked back at my old binders very much, but when I got the ChessLecture gig, they were a fantastic resource! One funny thing I noticed last year was that I’ve had a really remarkable number of combinations over the years that involved passed pawns in the middle game. Some people play sacs on h7 or f7, but it seems as if my specialty is passed pawns! This really surprised me, because you don’t see passed pawns mentioned very often in chess books as an ingredient in middle-game combinations. You usually think of them as something that becomes important in the endgame.

A couple weeks ago I decided that I was finally going to do my lecture on “Passed Pawns in the Middlegame.” So the first task was to go back over those old games — I found about six or seven that involved passed pawns — and pick the most instructive ones. That ruled out games where my opponents made a horrible blunder, or games where the passed pawn occurs only in the analysis. Here are two great games that didn’t make the cut:

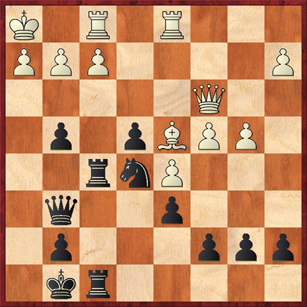

If you want to treat this game as a quiz, see if you can find the winning move for Black.

In this position I’m Black against Emory Tate, one of the best attacking players in America. But here the shoe is on the other foot: I’m the one with a dangerous kingside attack. But in this position I gave away my advantage with the very reasonable-looking move 22. … Nd3? Tate immediately showed that he is a good defender by sacrificing the exchange with 23. Rxd3! ed 24. Qxd3. Probably the position is still equal here, but I came unglued because my intended response, 24. … Rxf2 25. Qxg6 Rxf1+ fails to 26. Bg1! Instead I played a passive move, 24. … Qh7, and Tate seized the initiative (not to mention the e-file) with 25. Re1 and won a few moves later.

So what should Black do in the above position? The answer is a move that I would never have dreamed of in a million years: 22. … g3!! Of course, the computer found this move. This is a berserk pawn move, all right, but it doesn’t quite qualify as a “berserker pawn” as defined in my lecture, because it’s not a passed pawn yet. Yet!

What are the points of 22. … g3? White can take three different ways. 23. fg?? would, of course, lose to 23. … Rxf1+. Also losing quickly is 23. hg?? Qh5+ 24. Kg1 Ng4 with a mating net. But what’s wrong with 23. Qxg3? The answer is 23. … Qxg3 24. hg Nxc4 and now the threat of 25. … e3 is just a crusher. In this case it turns out to be the e-pawn, not the g-pawn, that is the berserker pawn. Best play for White is 25. Rc1 b5, and White’s d-pawn is going to fall.

Finally, another important try for White is 23. Bxe5, hoping to get rid of the knight, which played an important role in the above variations. But even now, Black can play 23. … de 24. Qxg3 Qxg3 25. hg e3!, and the berserker pawn strikes again. Black threatens e3-e2, and White will have to give up the f-pawn. Perhaps it’s not completely clear that Black is winning, but the computer gives him a one-pawn advantage.

This was an amazing variation, but I decided not to put it in my lecture because: a) It didn’t actually happen over the board, and b) The berserker pawn theme is obscured by several other complications.

Here’s another one that didn’t make the cut:

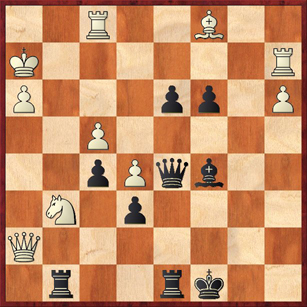

A couple years ago in Reno, I got to this position against an expert named Hans Morrow. I had made a blunder a few moves earlier, and instead of defending a bad position I decided to make a game of it and sacrifice a piece to get two ferocious-looking passed pawns on d4 and c4.

I think that the main reason Morrow lost this game was that he played too many “spite checks,” checks that served no real purpose. In this position his biggest problem is how to activate his bishop, and the best solution is 27. a4! Not only does this prepare Ba3, but it also forces Black to worry about how to stop White’s own passed pawn.

Instead Morrow played the spite check 27. Qa4+? Kf7 28. Ra2 Bf8, and now he belatedly realized that his queen is doing nothing on a4 and is actually in the way. Note, by the way, that I did not rush to play 28. … d3, because I didn’t want White to take over the g-file with 29. Rg2. Also, I felt that it was best to keep the pawns side by side as much as possible, so that they would not be easily blockaded.

Now White admitted his mistake with 29. Qd1 and we mucked around for a few more moves, arriving at this position:

White has won another pawn and chased Black’s king over to the queenside, but ironically the king is perfectly safe there, while White’s queen and knight are dangerously far from the main action. Also, Black has managed to advance his pawns one square each, so that again they cannot be blockaded.

Here White’s only move is 35. Rg2, and the position is still extremely unclear. But instead my opponent blundered with 35. Be3??, either overlooking the fact that I was attacking his rook on a2 or overlooking the fact that I capture with check. After 35. … Qxa2+ 36. Rf2 Qd5 I am now ahead in material, plus I still have the two nightmarish passers on c3 and d3! My opponent resigned seven moves later.

This was an exciting game, but I decided it wasn’t right for my lecture. First, my original sacrifice was completely unsound, and I should have lost the game. Second, the game didn’t really fit with the themes of my lecture. My other examples of berserker pawns involved just one pawn that suddenly goes berserk, but this game has two, and they actually advanced very slowly.

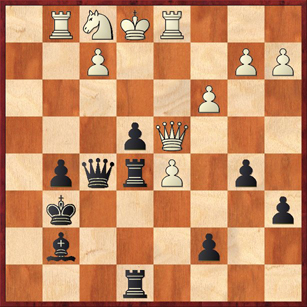

So what did make it into the lecture? Here is my prototypical example of a position where a pawn goes suddenly berserk. (Kaplan-Mackenzie, U.S. Class Championship 1985)

Looking at this position, would you believe that Black is going to queen a pawn in three moves? But that’s exactly what happened:

31. … e3! 32. f4? …

White had to play 32. fe, but he loses his queen for two rooks after 32. … Rxe3+ 33. Qxe3 Rxe3+ 34. Nxe3. More to the point, Black’s queen and bishop will make an effective attacking force after 34. … Qf3. White’s king is quite exposed, and his rooks are not coordinated.

Perhaps White thought that the threats of 33. Rxg5+ and 33. fe would stop my pawn advance, but he was mistaken. The pawn on e3 is now certifiably berserk.

32. … e2! 33. fe …

Also losing is 33. Rxg5+ Qxg5 34. fg edQ+ 35. Kxd1 Re1+, with 36. … Bxd4 next.

33. … edQ+ 34. Kxd1 Rxe5

And now the threats of … Rxd5 and … Qb1+ are unstoppable. The game ended 35. Qg4 Qb1+ 36. Kd2 Qxb2+ White resigns.

So what is a berserker pawn? Well, remember that I was originally going to call my lecture “Passed Pawns in the Middlegame.” But I realized that the term “passed pawn” is inadequate to describe the e-pawn in this game, and others like it. A passed pawn is a tame creature that has to be nourished until the endgame, when he can start to make his presence felt. A berserker pawn is a savage creature that stampedes through the opponent’s position without warning. Of course, a berserker pawn is a passed pawn, but it’s more than that: it’s a passed pawn that the opponent cannot effectively blockade. There are several reasons your opponent might not be able to blockade it. He might simply not have enough time. (In the above game, White was too late to blockade on e3.) Or perhaps you have control over the potential blockading squares. Or, also as in the above example, your berserker pawn may be attacking some pieces as it charges forward. Here, for example, White did have a blockade set up on e1, but it didn’t matter because when the pawn advanced to e2, it forked the knight and rook and thus was guaranteed of being able to turn into a queen.

I also noticed a little trick that often goes along with berserker pawns. Sometimes the opponent thinks he has set up a blockade, but cannot hold it because of the following tactical motif:

This is from Pearson-Mackenzie, Western States Open 2001. It seems as if the berserker pawn on e2 is going to come to a sad end, but the rook on e8 comes to its rescue in a surprising way: 30. … Rd8! White sees too late that if he moves his knight away, say 31. Nc4, Black will play 31. … Rd1. The poor rook on e1 is in a quandary. He can’t take on e2 because he’s pinned, he can’t take on d1 because that lets the pawn queen, and if he moves away from e1, the pawn will queen on e1. This is a common trick in rook-and-pawn endgames. I don’t know if it has an official name, but I decided to give it one: the “back-rank blockade buster.”

By the way, Pearson actually played 31. Rxe2, giving up the knight, and I won easily after 31. … Rxd6.

There’s plenty more to see in my lecture. (You didn’t think I would tell you everything, did you?) I went over two more examples from my own games, plus an absolutely stellar example from the game Larsen-Spassky, USSR vs. World match, 1970. It was really neat to look at this game again, many years after seeing it for the first time. I had a vague recollection that Spassky sacrificed a piece to obtain an unstoppable passed pawn. It turned out to be even better than I remembered, and it fit perfectly with the themes in my lecture. Not only did Spassky get a berserker pawn, but he was able to promote it by playing not one but two “back-rank blockade busters”! I think it’s fair to say that I did not understand this game previously, but once I started thinking about it in these terms, it made perfect sense.

This was one of my favorite lectures to give, because I actually managed to teach myself some new things. I hope that you liked it (or will like it) too!

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

any ideas on how to contact emory tate? I knew him back when we were in the air force. Please let me know. Thanks, Kerry Sinclair

Kerry,

I’m afraid that I don’t know any contact information for Emory Tate. He seems to play in most of the big U.S. chess tournaments, so if you’re in Las Vegas June 6 to 8, I’ll bet you can find him at the National Open. But that’s probably not very practical for you. I wish I could be more helpful!