If I ever write that book of amateur games told in “story” fashion (or “melodramatic,” a word some of our readers took issue with), here is one that I will have to include.

This was the game between Dan Burkhard (White) and Jeff Mallett (Black) from last Sunday’s round of the Santa Cruz Cup. First of all, it has one ingredient that already makes for a good story: it was personally important to both players. Remember that they are both vying for the fourth playoff spot in our tournament, and whoever won the game would be in the driver’s seat.

Dan played the Stonewall Attack, and right away things started going well for Jeff: he was able to play … g6 and … Bf5 and exchange off his bad bishop, while leaving White’s bad bishop still on the board. This pawn structure also gave Jeff an unassailable strong point for a knight on e4, while White’s knight on e5 could be driven away by a timely … f6.

But the position remained very closed. The last time I saw the game, just after the time control on move 40, each side still had two rooks, a queen, and a bishop in addition to an almost full complement of pawns. I didn’t know who was going to win, but I was sure that it was going to come down to a time scramble, because the second time control was sudden death and I didn’t expect the game to come to a crisis for many moves yet.

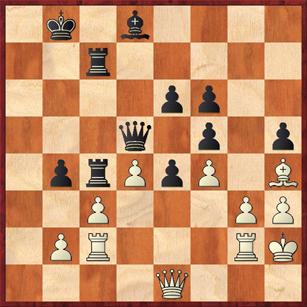

Well, actually the crisis started around move 47, and kept going for 15 more moves! Here’s the position:

Jeff has just moved his rook (on h7) to c7, building the pressure on the c-file. It is interesting that the computer actually recommends 46. … b3 instead, a move I disagree with. This is another example of the computer not being aware of the implications of a blockaded position. Black should only play 46. … b3 if he is absolutely clear that he has a winning plan. For example, if Black were certain that he could penetrate to the back rank, then I would say 46. … b3 is okay. But I think after 47. Rc1 Ra7 48. Qd1 Ra5 49. Rd2! (White is not tempted by the h-pawn, because taking it would allow Black to achieve his objective) it’s not clear how Black makes progress. If he moves his queen away from d5, then d4-d5 is coming and White opens up the position in a favorable way.

There’s another point here, which is that Black can play … b3 any time he wants. But once he plays it, then he loses any chance of breaking through on the c-file. So Jeff’s move, 46. … Rhc7, made much more sense because it is more flexible. It keeps all the options open, and thereby makes it harder for White to defend. Stupid computers …

In fact, Jeff’s move paid benefits right away. Because in the diagrammed position, Dan finally ran out of patience and played 47. g4? Maybe he just got tired of having his bishop hemmed in. Maybe he missed Black’s 49th move. Or maybe he was already eyeing the h2-b8 diagonal for his Bishop. I don’t know. But I do know that in “positional squeeze” games, it’s usually the defender who runs out of patience first. This is another thing that computers don’t know. Of course, the computer says White should play 47. Rc1 and just hold on tight. It’s hard for Black to break through on the c-file for two reasons: his King becomes exposed after any pawn trade on c3, and also his h5 and f6 pawns may fall if he commits all of his pieces to attacking c3.

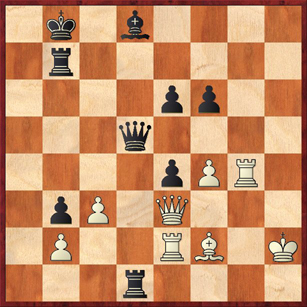

So, after 47. g4, we get the following sequence: 47. … hg 48. hg fg 49. Rxg4 Rxd4! (Did Dan maybe miss this?) 50. Bf2 Rd1 51. Qe3 b3 52. Re2 Rb7, arriving at the following position:

Things are looking a lot more grim for White now because he has allowed Black to penetrate into the heart of his position. But here Dan makes an amazing, inspired decision (which, once again, the computers completely fail to understand). He plays 53. f5!?! What are the points of this move? Well, first of all, he saw the trap that Jeff set: 53. Qxe4? loses to 53. … Qxe4 54. Rxe4 f5. Secondly, 53. f5 is a line-opening move for White, and at the same time it is a line-closing move for Black. It does basically three wonderful things at once. It opens the fourth rank for the rook to attack the pawn on e4. This forces Black to play 53. … ef in order to defend the e4-pawn. But that capture closes the fifth rank for Black’s Queen. In some previous variations, … Qh5 was a very serious threat. Not any more! Finally, and most importantly, 53. f5 opens the h2-b8 diagonal for White’s bishop, which turns out to be crucial in the later play. Positionally, this was a master stroke.

Tactically, 53. f5 is a disaster, and that is all the computer cares about. The game continued:

53. … ef 54. Bg3+ Kc8 55. Rh4 Rd3 56. Qf4 …

Take a look at this position and see if you can figure out how you would play it for Black.

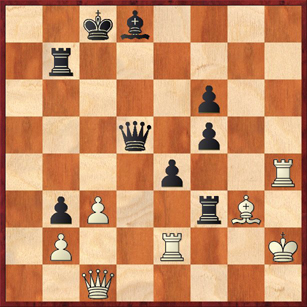

Now comes an amazing series of moves. For four consecutive moves, the specter of the exchange sacrifice … Rxg3 looms over the position. And each move, Jeff decides to do something else instead. After 56. … Rxg3, Fritz says that Black is about 5 pawns ahead. After 57. … Rxg3, Black is 8.5 pawns ahead. After 58. … Rxg3, Black is 7 pawns ahead. And after 59. … Rxg3, Black is an astounding 13 pawns ahead!! From the computer’s point of view, the game is completely over.

But humans are a little bit different. Remember that both players are now in a time scramble. I don’t know the time situation exactly, but I was told that at the end of the game Dan and Jeff were both down to 3 minutes. The thing is, once you play … Rxg3, the game enters the orbit of pure tactics. If you have just 5 minutes or 10 minutes left for the whole game, and you’re looking at the above position, how sure are you of your analysis of the sacrifice? Are you willing to wager the whole game on it? Especially when you have some good, obvious, moves that strengthen your position?

Jeff didn’t roll the dice. He played:

56. … Rf3

A natural move! If 56…. Rxg3 57. Qxg3 Bc7 58. Rh8+ Kd7 59. Rh7+ Kc6 60. Rxc7 Rxc7, the computer looks at the position and says Black is completely winning. The human says, well, I’m two pawns up, but there is still a lot of work to do, and I definitely have the feeling I should have gotten more out of the position. So 56. … Rf3 looks a lot more attractive.

Dan played 57. Qc1. Should Black sac the exchange now?

“Yes, yes, yes!” says the computer. After 57. … Rxg3 58. Kxg3 Rg7+, which way does the king go? If he goes to f4 or f2, he gets mated after the bishop check. Similarly if 59. Kh2 Bc7+ 60. Kh1 e3+! is curtains. So he has to play 59. Kh3. But now Black plays the quiet move, 59. … Bc7!, and the mating net is closing around White’s king. After the spite check 60. Rh8+ Kb7, there’s nothing left for White to do. 61. Qa1 Qd3+ forces mate. So does 61. Re3 Qe5.

Here’s where I think that computer chess and human chess do converge. In this position Black has to realize that the time is ripe for the exchange sacrifice. He has to see, as Jesse Kraai would say, the “Polgar mates” that are all over the place in this position. Maybe it’s a little bit scary, in a wide-open board with both kings exposed, to play a quiet move like 59. … Bc7!, but Black has to remember my ChessLecture on mating nets. You almost always need a quiet move to close the net.

But again, there are only five minutes left, and Jeff still thought he had sensible ways to strengthen his position. White is threatening 58. Rd2, so he plays 57. … Rd7, clamping down on the d-file. The game continues 58. Qa1 Kb7 (58. … Rxg3!) 59. Qa4 Bb6? (59. … Rxg3!) Notice that by continuing to react to White’s threats, instead of playing aggressively, Black has given the initiative to White. Black’s moves are not getting him any closer to his goal, while White’s moves have gradually created serious threats on Black’s king. Now the storm breaks:

60. Rh8 Rd8?? According to the computers, Black is still winning, just barely, with 60. … Bg1+. But in reality, Black has lost control over the position. Maybe the practical thing to do was bail out into an immediate draw wtih 60. … Ba7 61. Qb4+ Ka6 62. Qa4+. But that’s really hard to do, when you know that you were winning just a few moves ago.

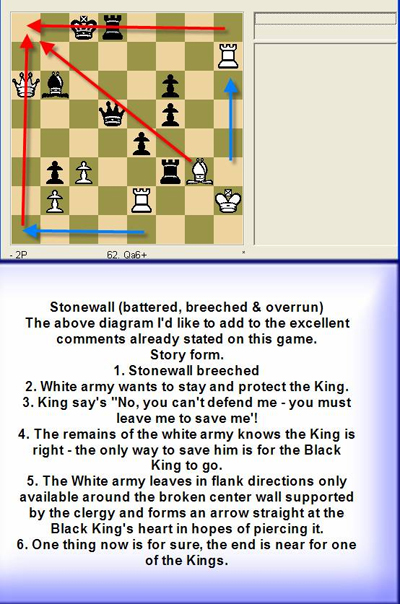

And now the triumph of White’s idea with g4 and f5 is complete. All of White’s pieces now control the key lines heading to Black’s king, and the game ends with

61. Rh7+ Kc8 62. Qa6+ Black resigns.

A fantastic triumph for Dan. A truly heart-rending defeat for Jeff. I mentioned in my last post that when I hung a pawn against Ilan Benjamin, it felt to me like “the worst blunder in chess history.” Well, it turns out that it wasn’t even the worst blunder of the day!

Why did White win? In a desperate position, he came up with a clear plan of attack. He forced his opponent to think, instead of playing on autopilot. He was not afraid to give up large amounts of material in order to get his pieces on good lines.

Why did Black lose? In a crushing position, he failed to come up with a clear plan of attack. He continued playing generic, positional moves in a position that called for a tactical solution. He was afraid to give up material in order to get his pieces on good lines.

Dan was so inspired by this game that he e-mailed us a “storyboard” for it. I think you’ll appreciate it. Here is the melodramatic … er, dramatic version of the game:

I think that this game should be called “No Country for Old Men.” The “old men” are the kings, and in a position like this, with queens and rooks and bishops running rampant on an open board, there is indeed no place for a king to hide!

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Indeed, it is a beautiful amateur game. I tell you this has more excitement than some near-perfect grandmaster games I have seen. Please give my kudos to Dan. What an inspired game! I would love to play against him.