Many of you have probably already seen the game from earlier this month where Viswanathan Anand destroyed Alexei Shirov (as Black!) in 17 moves. However, I feel as if I should say something about it because it is an ultra-rare appearance in top-level chess of an opening variation I have played many times and blogged about:

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. e5 Bf5 4. g4!?

Initially I called this the Homo Erectus Variation. I was inspired by Michael Goeller’s “Caveman Variation,” where White plays 4. h4. I named it thus because I was looking for something that is even more primitive than a caveman. Unfortunately, this name sounds a little bit too salacious, so after awhile I tried renaming it “Bronstein’s Folly” because Bronstein played it once against Petrosian. (They drew.)

Now perhaps it will become known as “Shirov’s Folly.”

The crazy thing is, it’s still playable. But because of Shirov’s debacle I think it will be a long, long time before we see it again on the top level.

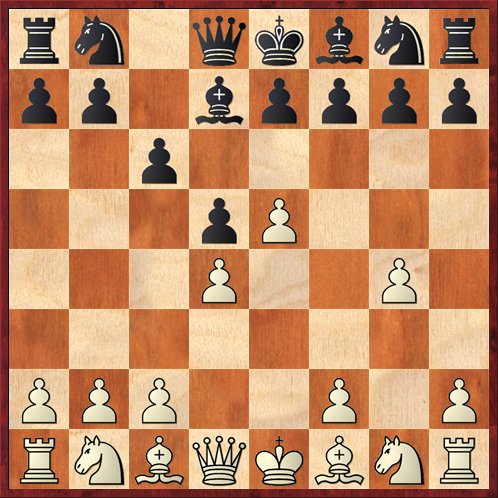

Anand played 4. … Bd7 (diagram). As I mentioned in my series on Bronstein’s/Shirov’s Folly, this move immediately shows you the caliber of your opponent. All of the masters I have ever faced in this variation have played this move, and almost none of the sub-2200 players have!

Position after 4. … Bd7.

Why do masters like this move so much? To an amateur, it seems paradoxical. Black plays the Caro-Kann because he wants to develop his queen bishop outside the pawn chain, and yet here he meekly retreats it back to the “wrong” side of the chain.

The master, on the other hand, realizes that the position has fundamentally changed. It’s no longer about Black’s bishop, but about the looseness of White’s pawn structure. If Black can simply avoid allowing weaknesses in his own position (as he is forced to in the 4. … Be4 and 4. … Bg6 lines), he should eventually be able to call White to account.

Furthermore, the master may realize that the light-squared bishop has three (!) diagonals that are potentially more effective than the b1-h7 diagonal. First, on its present diagonal the bishop eyes the weak g4 pawn, which will be uncomfortable for White unless and until Black closes the diagonal with … e6. Second, White has weakened the long a8-h1 diagonal. Finally, if White fianchettos his king bishop (which appears likely, to shore up the long diagonal) and Black plays … c5 (which appears likely), then the a6-f1 diagonal also becomes very effective for Black’s bishop. Far from being a bad bishop, the bishop at d7 actually has rosy prospects, as we’ll see in the Anand-Shirov game.

From the above position, Shirov played 5. c4 e6 6. Nc3, following the Bronstein-Petrosian game, and then Anand uncorked his novelty. White’s idea is to continue putting pressure on the d5 pawn, not allowing Black the chance to free himself with … c5.

Which is why Anand’s next move must have shocked Shirov. He played 6. … c5!

Well, this shouldn’t have been a surprise. Even though it had never been played before in a master game (at least according to ChessBase), it makes perfect sense. Black is offering a pawn sacrifice, but in order to accept it White has to expose all the weaknesses in his position. Not only that, this move conforms to the general principle, “To refute an attack on the wing, you should counterattack in the center.” Also, the crippled pawn at g4 (which is exposed to attack again by the pawn exchanges in the center) is very likely to drop off at some point, after which Black won’t even be a pawn down.

The wonder is that nobody thought of this before. Petrosian didn’t play it against Bronstein. I somehow completely failed to notice it in my previous blog post. Shame on me.

I’m not going to analyze the rest of the game in detail. Shirov did in fact exchange twice in the center with 7. cd ed 8. dc Bxc5. Here the computers and the computer-inspired analysis on ChessBase.com suggest that White can in fact take the pawn on d5 with 9. Qxd5?! Bc5 10. Bc4 Be6 11. Bb5+ and survive. But it’s a very grim sort of survival, and not something that would appeal to human players.

What happened instead was very curious. Both sides finished developing their pieces in the most natural way, and then White resigned! The remaining moves were 9. Bg2 Ne7 10. h3? (Too slow — this appears to be the losing move. Better was 10. Ne2.) 10. … Qb6 11. Qe2 O-O 12. Nf3 d4! 13. Ne4 Bb5 14. Qd2 Nbc6 15. a3 Ng6 16. b4 Be7 17. Bb3 Rfd8.

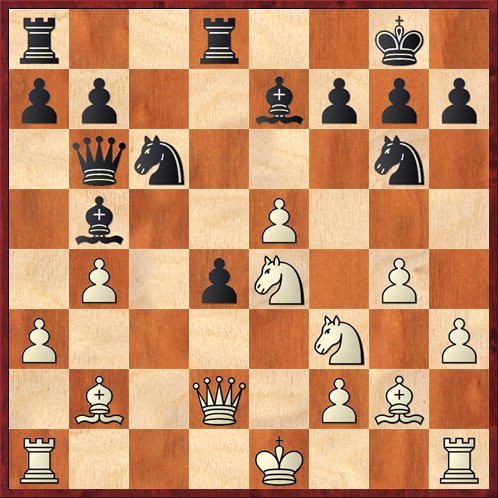

White to play and resign.

And here Shirov threw in the towel! This is one of those “grandmaster resignations” that sometimes leaves amateurs perplexed. And even a little bit cheated. When you see a decisive miniature (under 25 moves) game between grandmasters, of course you have to assume somebody goofed, but you also hope to see some kind of clever trick or brilliant sacrifice. There was nothing like that in this game. Both sides just developed their pieces, and then it was over.

So why did Shirov give up? Well, Eugene Perelshteyn expressed it very nicely in his ChessLecture. He said, “All of White’s pieces are well developed except his king.” And that’s exactly the problem. He can’t do anything until he gets his king to safety. The obvious move is 18. O-O-O; nothing else is really worth looking at. And after 18. O-O-O Black has a choice of three tremendous answers: either 18. … a5 (opening up the a-file with most likely lethal consequences) or 18. … Rac8 (completing his development, threatening a discovered check), or probably best, Perelshteyn’s recommendation of 18. … Ngxe5. Black simply wins a pawn, and maintains all the pressure.

There is one subtlety here, though, and it’s why as White I would not have resigned yet. After 18. O-O-O Ngxe5 19. Nxe5 Nxe5 20. Bxd4, if Black plays the obvious 20. … Nd3+?, intending to win a piece, it backfires after 21. Qxd3! Bxd3 22. Bxb6 ab, and White is fine!

Instead, Black has to play the intermezzo 20. … Rc8+!, when White has no good defense. 21. Kb2 allows the nasty fork 21. … Nc4+, and either 21. Kb1 or Nc3 allow 21. … Qa6!, which is very strong. For example, 21. Nc3 Qa6! 22. Qb2 Nd3+ picks up the exchange. Basically, White has too many weaknesses to defend — the a3 pawn and the squares c4 and d3.

I’m sure that Shirov saw all this, or most of it, and assumed that his world champion opponent would not overlook the shot 20. … Rc8+. In his shoes, however, I not have resigned until Black actually played that move, and even after that I would probably soldier on to move 30 or 35 or so. But for him, it was not worth the embarrassment.

So where does this leave the assessment of Bronstein’s/Shirov’s Folly? In my previous post, I wrote the following about White’s four options after 4. … Bd7:

(A) 5. Bg2 (okay)

(B) 5. Nc3 (not so good)

(C) 5. c4 (interesting)

(D) 5. Nd2! (perhaps the best).

Now we have to revise (C) to “dubious” or “interesting only for Black.” However, we can also change the assessment of 5. Nd2! to “clearly the best.” This move is directed against Black’s counterplay with …c5. It doesn’t actually prevent … c5 but it does exact a positional concession from Black — he has to give up his dark-squared bishop. One look at the Anand-Shirov game will convince you what a huge difference that makes.

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

NIce post, Dana. Interestingly, IM Ginsburg has a very different take on the whole variation in

http://nezhmet.wordpress.com/2008/10/23/the-fabulous-00s-chess-opening-blog-meet-the-soviet-logical-aesthetic/

He claims that “The cowardly 4… Bd7” is strongly answered by 5 c4!, but I guess Anand’s novelty will make this assessment a lot less clear. Instead, he favors 4…Be4!, where White’s pawn structure is weakened even further.

Superb weblog here! Also your internet site loads up very quickly! What host are you employing? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my website loaded up as quick as yours lol xrumer

Wow – great post! I happened to face this monstrous line yesterday at Kolty and nearly botched it. 4…Bd7! is an obvious move if you’re a French devotee (as I am, or rather, used to be). The point is that this then becomes an advance French, with the notable difference that white has weakened his kingside with g4.

Furthermore, the same theme features in the fantasy line where white plays f3. Black – for those pusillanimous souls who live, or die, without making war – plays e6, pretending that it is a French.