The quarterfinal matches in the World Championship Qualifier are now complete, and my description of the tournament as “May Madness” is now even more appropriate than ever.

First, just as in March Madness, upsets were the order of the day. The winner in three out of four matches was the lower-rated player: Gata Kamsky defeated Veselin Topalov, Boris Gelfand beat Shakhriyar Mamedyarov, and Alexander Grischuk got past Levon Aronian (the highest-rated of all the eight contestants) in tiebreaks. The only match that went “according to form” was Vladimir Kramnik beating Teimour Radjabov. But even that took a miracle!

Another hallmark of March Madness (the NCAA basketball tournament) is the number of games decided “at the buzzer” or in overtime. That was certainly the case here. Kamsky’s win over Topalov was the first to go down to the buzzer. Kamsky needed only a draw to advance, of course, but Topalov got a lot of pressure and Kamsky got in intense time pressure: at one point, he had just 1 minute left to Topalov’s 12!

Under such circumstances even such a solid player as Kamsky will crack. He made a blunder just before the time control that gave Topalov a winning advantage, so that the computers were showing a 3- or 4-pawn advantage for the Bulgarian. However, it’s one thing to have a computer advantage and another to actually realize it. The position was ferociously complex; Topalov had a queen and two bishops versus Kamsky’s queen and two knights, and neither king was very safe. Topalov had to find a way to set up a mating net before Kamsky could catch him in a perpetual check. He couldn’t do it — even with plenty of time left on his clock (as they had now passed the time control).

Kramnik came up with an even more amazing save the next day (May 9). Now we’re already into the “overtime” period. Kramnik and Radjabov had drawn all four of their long games and all four of their 25-minute playoff games, so next they went to 5-minute games. Here you would have to think Radjabov was the favorite, as he is younger and Kramnik (per his own admission) doesn’t play that much blitz. And indeed, Radjabov won the first blitz game in beautiful fashion and was 21 seconds away from drawing the second game and winning the match. They got to this position, with Kramnik having 21 seconds to play and Radjabov 12. (Note, however, that there was a 3-second time delay, so Radjabov still had at least 3 seconds to make every move.)

White to move.

Black has just played 60. … Kf6, which turned out to be a fateful choice. He pressed his button… and the clock broke! It showed 0 seconds for both sides. The players had to take a break for several minutes while the arbiters decided what to do and a new clock was found.

When play resumed, Kramnik played 61. Bc2! Rd4 62. Bb3! Suddenly a mate threat has appeared on the board, and Black has only one way to stop it: 62. … Be7.

Now White’s prospects have improved immensely. He plays 63. Bc4, putting his bishop on a defended square so that he can bring his king to g2-f3 etc. Notice that all of Black’s pieces are tied down: his bishop can’t move, his pawns can’t move, his king can’t move. Only the rook can move.

Here Radjabov made an unfortunate choice: he went into a defensive shell. It’s easy to do — that tends to be my automatic reaction in a time scramble. But Black needs to keep his rook active, and that means playing … Rd2 (my choice) or … Rd1 (Rybka’s choice). The rook will eventually go to the b-file, where it can both protect the b6 pawn and also harass White’s a4 pawn.

Instead, Radjabov played 63. … Rd6? (not losing yet, but the question mark is because it’s the wrong plan) Now Kramnik just waltzed his king up the board: 64. Kg2 Rd2+ 65. Kf3 Rd6 66. Ke4 Rd8 67. Bd5! (Closing the door on Black’s rook. Now it is forced into an exclusively passive position.) 67. … Rd6.

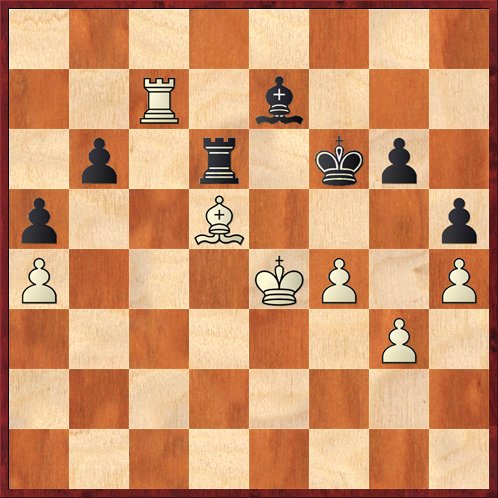

White to move.

This position should be tattooed on the arm of every player who has ever thought that bishops of opposite colors mean “a dead draw.” As long as there are rooks on the board, it ain’t necessarily so. The rook and the bishop can combine to make life uncomfortable for the opponent’s king. This position is a classic example, where Black can’t defend even though material is even. White plays 68. Rb7!, and Black is in zugzwang. If Black could just pass, the game would be a draw, but any move loses material. Radjabov played 68. … Rd8, Kramnik collected the b-pawn with 69. Rxb6+ and won the a-pawn a few moves after that. With two widely separated passed pawns, it was then a book win for White.

Of course, that wasn’t the end of the match — it only meant that Kramnik had tied the first overtime round, 1-1, and the players would play two more speed games. But from the psychological point of view, it had to be devastating for Radjabov, who lost both of the next two games. With this heart-pounding victory, as exciting as any basketball game, Kramnik moves on to face Grischuk, who likewise defeated Aronian “in overtime.” (He managed to triumph in the 25-minute games, so they didn’t need to go to the 5-minute games.)

Watch out for Grischuk! As the substitute for Magnus Carlsen, he was the “last one to qualify” for this tournament. As anyone who has followed the NCAA basketball tournament knows, you’ve got to watch out for the bubble teams. This year Virginia Commonwealth (VCU) was “last to qualify,” and they went all the way to the Final Four. Could Grischuk be the VCU of this tournament — or even better?

I don’t know if this is a good way to pick a world champion, but it is a good way to make chess entertaining!

Of course, all of the events here are described in detail on lots of other sites. I especially recommend Chessbase (www.chessbase.com) and Chess in Translation (www. chessintranslation.com), which also has an excellent translation of Kramnik and Radjabov’s post-playoff press conference. Interestingly, “MishaNP,” the host of Chess in Translation, comments there that Kramnik looked exhausted at the press conference, while Radjabov, who had just lost, still seemed to have lots of energy. He’s young, and can take this as a learning experience.