In February, there is no question that the center of the chess universe is Russia. There are two huge events, back to back: the Moscow Open, with a prize fund of 5 million rubles ($200,000), and the Aeroflot Open. The Moscow Open “A” tournament, which ended on February 10, had 302 participants, including 95(!) grandmasters. I doubt that you can find this kind of competition anywhere else in the world.

Four brave Americans made the pilgrimage to Moscow, two of them from the Bay area: David Pruess and Josh Friedel. Both of these names should be familiar to you. In December I wrote about David’s second GM norm. Also, I did a joint lecture with Josh at ChessLecture about our game in the CalChess Labor Day tournament. Strangely enough, Josh hasn’t recorded anything for ChessLecture since then. I don’t know why. Too busy?

The other two Americans at the Moscow Open were grandmaster Gregory Kaidanov and Irina Krush, who played in the women’s section. As you can read at the USCF website, Irina had the best tournament of the four. She went 6-3, but ended with a disappointing loss on board two in the last round. As for the men, Kaidanov and Friedel scored 5½-3½ and Pruess went 4½-4½. I think that’s a decent result for all of them, even if Friedel and Pruess didn’t get what they came for (grandmaster norms).

I think that Josh especially should be happy with his result. Look at all the famous GM’s he tied or finished ahead of: Akopian (at 2700, the highest-rated player in the tournament!), Tiviakov, Najer, Sveshnikov, Fedorov, Dreev, … And his last-round win, against a 2300-ish Russian named Gusar Moiseev, was absolutely spectacular. Here is how the big boys play:

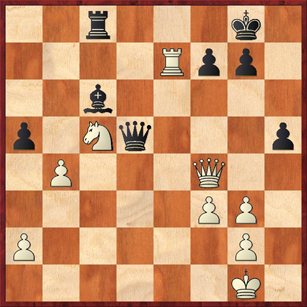

Josh played the 8. d4 anti-Marshall variation in the Ruy Lopez. According to the computer, he and his opponent were more or less equal until Moiseev missed a back-rank threat on move 25 and lost a pawn. But Josh was just getting started with the combinations! In the above position, what is White’s best continuation?

After you’ve solved this, it’s interesting to backtrack a couple moves. White had just moved his queen from c4 to g4 (29. Qc4-g4), Black chased it with the h-pawn (29. … h6-h5), Josh moved from g4 to f4 (30. Qg4-f4), and then Black moved his bishop from b7, where it was attacked twice (30. … Bb7-c6). Sometimes the little subtleties before the winning combination are just as interesting as the combination itself. Why didn’t Josh just play 29. Qf4 straight away, instead of playing 29. Qg4 first? To put it another way, what difference does it make whether Black’s pawn is at h6 or h5?

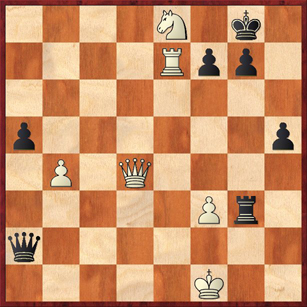

Now let’s move forward a few moves.

One thing about the big boys is that they play tough defense. Moiseev didn’t bat an eye at Josh’s combination. He gave up his bishop, and created some murderous-looking threats against White’s king. In the above position, how on Earth can White continue his attack without getting checkmated himself?

If it makes you feel better, I was not able to figure this one out. I looked at it for ten minutes, and couldn’t find a single continuation for White that even kept an advantage. But Josh found a way. Oh boy, did he ever…

Solutions:

1. Josh got the fireworks started with 31. Ne6! If you see it, the point of this move is pretty obvious. It cuts Black’s queen off from the defense of f7. 31. … Rf8 would obviously drop the exchange, so Black’s only other possibility is 31. … Be8, which he played. Then Josh followed up with 32. Nc7! (no credit for you if you didn’t see this) and Black cannot defend both the e8 bishop and the f2 pawn.

2. The reason Josh played 29. Qg4 first was that he wanted to induce the move … h5 (which was basically forced, because Black’s bishop on b7 was hanging and if he moves it away, his rook on c8 is hanging). And the reason he wanted to do that was that it made the sacrifice 31. Ne6! much more powerful. If the h5 square had still been open, Black could have defended the crucial f7 square with … Qh5. So Josh’s clever two-step with the queen took away Black’s best defense.

In many ways the most important move of the combination was 29. Qg4, not 31. Ne6. If I saw the move Ne6! coming, I would have probably played it at the first opportunity. But instead Josh asked himself, “What can I do to make this threat stronger?”

The move 29. Qg4 also illustrates a point I’ve mentioned before in my lectures — “moving your opponent’s pieces.” Josh forced his opponent to move his h-pawn to a square where it would be in the way of the queen. When you can move your opponent’s pieces, you know you are in control of the position.

3. Josh’s sensational finish was 36. Qxg7+!! Rxg7 37. Nf6+, forcing mate in two. If you don’t see this queen sacrifice, you lose all of your previous good work! It would be interesting to know at what point Josh saw it. I doubt that he saw it at move 31; chances are he just saw that 31. Ne6 wins a piece, and that was good enough. But maybe he did see the queen sac that early, I just don’t know. I hope I’ll get a chance to ask him sometime.

When I looked at the position, I tried really hard to make 36. Nf6+ work, but after 36. … gf 37. Qxf6 Qg2+, Black just gets too many checks. In a way the idea of 36. Nf6+ was right — White is trying to checkmate Black on the back rank or in the corner — but the execution was wrong. I never even thought about offering the queen. That’s the difference between me and the big boys!

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

Rephrase problem number 3 as “white to play and mate in three” and everybody solves it. Tal gave sound advice: “if you don´t look you don’t see.” Conventional wisdom too: “examine all captures, checks and forced continuations.”

Make that mate in four.

Exactly right! This is a great example of how the way you think about the position determines the kind of move you’re going to play. If I had come to the position “cold”, with the eyes of a kibitzer, perhaps I would have spotted the queen sac right away. Instead I was struggling to figure out how Josh was going to quell his opponent’s counterplay. Because I was thinking in those terms, I spent 90 percent of my time analyzing all of Black’s myriad checks, instead of thinking about what *White* could do!

The popular wisdom is right, and the key word here is “ALL”. Even the checks that look ridiculous must be analyzed consciously, even if it’s only for five seconds. Don’t let your subconscious get away with dismissing a move before your conscious brain even gets to look at it.