New Year, Halos and Blue Moons

Sunday, January 3rd, 2010

Here in Santa Cruz, New Year’s Eve brought an unusual coincidence of two astronomical events. One of them was a worldwide event: It was the second full moon of the month, or a “blue moon.”

The usage of the term “blue moon” to mean the second full moon in a calendar month actually stems from a mistake in Sky and Telescope magazine in March 1946! This article on Sky and Telescope‘s website explains how the confusion arose. However, as the authors note, the new definition is “like a genie that cannot be forced back in the bottle.”

How often do blue moons occur? That is a very interesting question that you can figure out for yourself if you look at the chart on the bottom of page 2 of the article. The chart reveals an interesting fact that the authors do not mention: blue moons happen on a 19-year cycle.

To see this, notice that 1999 began with blue moons in January and March. Nineteen years later, the year 2018 will begin in exactly the same way. Why is that? Well, 19 is sort of a magic number for moon-lovers. It turns out that 19 solar years are almost exactly equal to 235 lunations. (A “lunation” is the time between one full moon and the next.) So that means if you have a full moon on December 31 this year, you will most likely again have a full moon on December 31 nineteen years from now.

There are only two things that can mess up this pattern. First of all, there is a tiny 2-hour discrepancy between 19 solar years and 235 lunar months, which eventually (over a period of twelve 19-year cycles) will move the full moon forward a day. The other discrepancy results from Leap Day. If you look again at the Sky and Telescope diagram, you’ll see that the blue moon of 2001 (in November) does not match the blue moon of 2020 (in October). According to our 19-year rule, they should be in the same month each year, but the blue moon in 2020 gets pushed forward a month because of the extra day that is inserted in February that year.

This 19-year cycle was very important in ancient times, because many cultures used both a lunar and a solar calendar. To bring the two into rough correspondence, you need 7 intercalated or “extra” months every 19 years. (That is, in 19 years there are 19 x 12 “regular” months, plus 7 “extra” months, for a total of 235.) The rule was discovered by Meton of Athens in 432 BC, and is therefore known as the Metonic cycle.

Unlike the Athenians, we use a purely solar calendar. The “months” in our calendar are no longer lunations; they are merely convenient fictions. For that reason, also, the Metonic cycle no longer has any direct effect on your life — unless you happen to be the kind of person who pays attention to blue moons!

By the way, there is one other intriguing thing about that Sky and Telescope chart. I have said that there are 7 “extra” full moons every 19 years, and so you would think there would also be 7 blue moons. But actually, that isn’t quite correct! If you look at the chart, you will count 8 blue moons from 1999 through 2017! Where did the extra one come from?

The problem is, once again, February. In 1999 there were no full moons at all in February, and therefore we had two in March as well as two in January. Thus, from 1999 through 2017 (the current Metonic cycle) we will have 8 months with an “extra” full moon and one month (February 1999) with none. In other words, we will have a NET of 7 “extra” full moons, just as we are supposed to.

**************

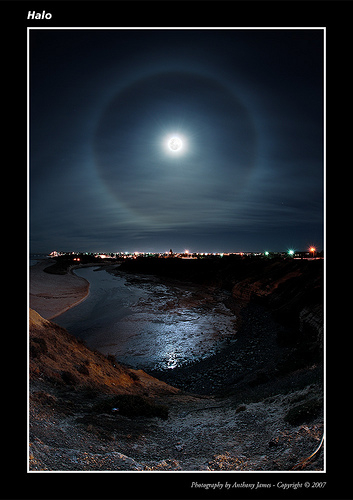

As I mentioned, there was other wonderful astronomical phenomenon on New Year’s Eve. This one was local, rather than global. When I went outside at ten minutes before midnight, I was stunned to see a beautiful, huge halo around the moon — just like the one in the photo at the beginning of this post. (By the way, that is not my photo. It was taken by an Aussie photographer named Anthony James, who kindly gave me permission to post it in my blog. Click here to see his Flickr page, which specializes in beautiful nighttime imagery.)

A lunar halo is much easier to understand than a blue moon. It is formed in the same way as a rainbow, by the refraction of light off of ice crystals or drops of water in the atmosphere. That night was very misty and cloudy here in Santa Cruz. In fact, according to the newspaper, we weren’t supposed to be able to see the moon at all that night. However, by 11:50 PM enough of the haze had evaporated that the moon was very clearly visible. However, there were no stars — it was as if everything in the sky had been turned off except this enormous eye looking back down at me.

That’s really what it looked like — an eye, or the photographic negative of one. The lunar halo looks like the iris and the moon looks like the pupil (white, instead of black!). I think that Anthony’s picture gives you some idea of the effect.

What an incredible night–a blue moon, an eye in the sky, and the beginning of the year, all at once! I’m certain that combination will never happen again in my lifetime.